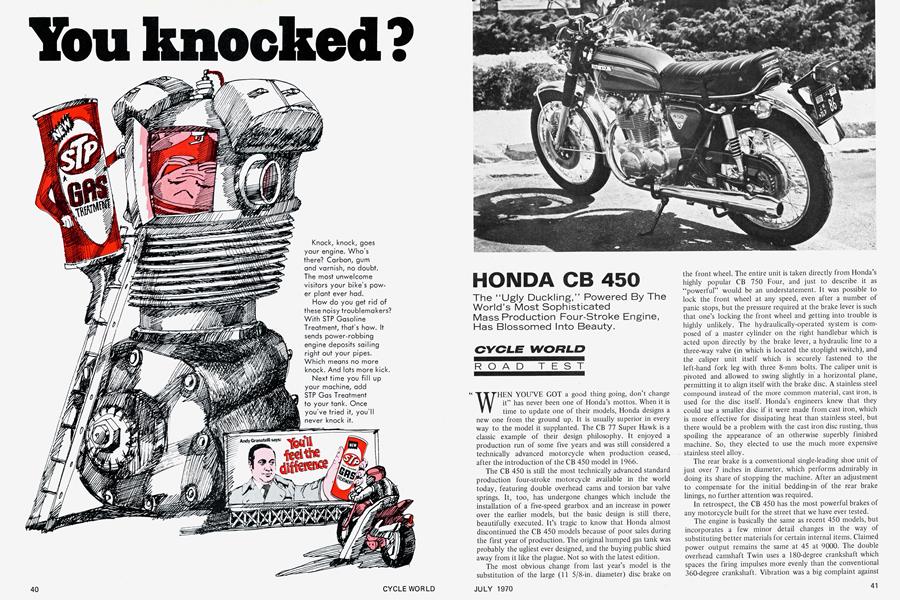

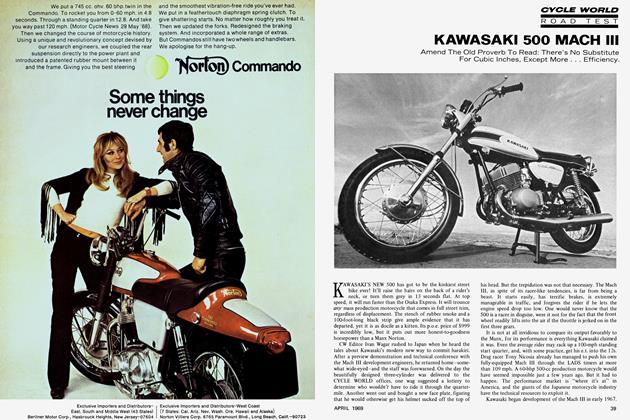

HONDA CB 450

CYCLE WORLD ROAD TEST

The "Ugly Duckling," Powered By The World’s Most Sophisticated Mass Production Four-Stroke Engine, Has Blossomed Into Beauty.

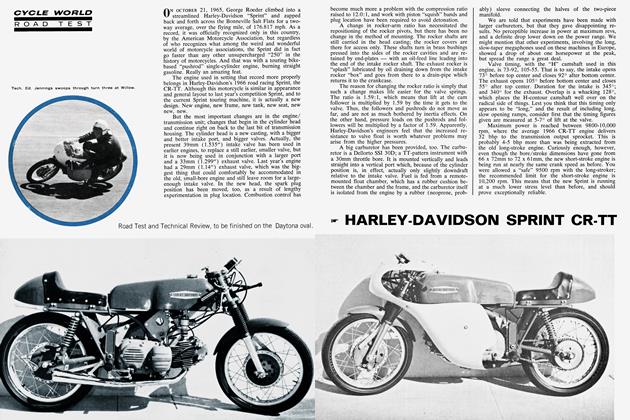

WHEN YOU'VE GOT a good thing going, don’t change it" has never been one of Honda's mottos. When it is time to update one of their models, Honda designs a new one from the ground up. It is usually superior in every way to the model it supplanted. The CB 77 Super Hawk is a classic example of their design philosophy. It enjoyed a production run of some five years and was still considered a technically advanced motorcycle when production ceased, after the introduction of the CB 450 model in 1966.

The CB 450 is still the most technically advanced standard production four-stroke motorcycle available in the world today, featuring double overhead cams and torsion bar valve springs. It, too, has undergone changes which include the installation of a five-speed gearbox and an increase in power over the earlier models, but the basic design is still there, beautifully executed. It’s tragic to know that Honda almost discontinued the CB 450 models because of poor sales during the first year of production. The original humped gas tank was probably the ugliest ever designed, and the buying public shied away from it like the plague. Not so with the latest edition.

The most obvious change from last year’s model is the substitution of the large (11 5/8-in. diameter) disc brake on the front wheel. The entire unit is taken directly from Honda’s highly popular CB 750 Four, and just to describe it as “powerful” would be an understatement. It was possible to lock the front wheel at any speed, even after a number of panic stops, but the pressure required at the brake lever is such that one’s locking the front wheel and getting into trouble is highly unlikely. The hydraulically-operated system is composed of a master cylinder on the right handlebar which is acted upon directly by the brake lever, a hydraulic line to a three-way valve (in which is located the stoplight switch), and the caliper unit itself which is securely fastened to the left-hand fork leg with three 8-mm bolts. The caliper unit is pivoted and allowed to swing slightly in a horizontal plane, permitting it to align itself with the brake disc. A stainless steel compound instead of the more common material, cast iron, is used for the disc itself. Honda’s engineers knew that they could use a smaller disc if it were made from cast iron, which is more effective for dissipating heat than stainless steel, but there would be a problem with the cast iron disc rusting, thus spoiling the appearance of an otherwise superbly finished machine. So, they elected to use the much more expensive stainless steel alloy.

The rear brake is a conventional single-leading shoe unit of just over 7 inches in diameter, which performs admirably in doing its share of stopping the machine. After an adjustment to compensate for the initial bedding-in of the rear brake linings, no further attention was required.

In retrospect, the CB 450 has the most powerful brakes of any motorcycle built for the street that we have ever tested.

The engine is basically the same as recent 450 models, but incorporates a few minor detail changes in the way of substituting better materials for certain internal items. Claimed power output remains the same at 45 at 9000. The double overhead camshaft Twin uses a 180-degree crankshaft which spaces the firing impulses more evenly than the conventional 360-degree crankshaft. Vibration was a big complaint against the earlier CB and CL 450 models, but our test machine was quite vibration-free except for a short period between 5300 and 5700 rpm; this all but disappeared a few hundred revs up or down the scale. Presumably, the crankshaft’s primary balance factor has been altered slightly from the earlier models, which accounts for this new smoothness. It is relatively easy to design out the primary imbalance in an engine, but the secondary (1st harmonic) resonances are much more difficult to get rid of, and are often directly related to the design of the engine’s mounting positions and provisions in the frame.

The Keihin constant velocity carburetors also contributed much to the smoothness of the bike. These are double tenturi units that have been modified with air-bleed holes in the carburetor throat which uncover as the throttle butterfly moves open. Another venturi is formed by the throttle slide, which rises in proportion to the amount of opening of the butterfly valve, and to the amount of air/fuel mixture the engine can use at any particular rpm and load factor. It is practically impossible to “flood out” the engine by blipping open the throttle too quickly.

Honda feels that their time has been well spent in designing, and subsequently modifying, this carburetor, and we agree wholeheartedly. There were no flat spots anywhere in the speed range of this engine, and no adjustments to the mixture were required throughout the test.

Perhaps the most unique feature of the CB 450 is the torsion bar method of closing the valves. Under torsion, the bar acts just like a helical valve spring in that it wants to return to its original shape after a force is applied. Both ends of the torsion bar are fastened to the cylinder head by means of serrated couplings, one of which is equipped with a dowel pin to set the pre-load on the bar during assembly.

The torsion bars themselves are manufactured from a silicon chrome alloy steel, which has great resistance to the twisting forces applied to it and yet is very resilient. The bars are heat-treated, ground to a critical diameter and shot-peened, and are then given an initial pre-load before installation. Due to the differing weights of the valves, the torsion bar assemblies are of different dimensions, twist in opposite directions, and are not interchangeable. In fact, replacement torsion bars are available only as a complete assembly, which includes the torsion bar and the receiver that closes the valve.

Although more costly and difficult to manufacture than conventional coil valve springs, Honda gives several reasons for adopting this system. First, the resonant frequency of a torsion bar is much higher than that of a coil spring, which precludes the phenomenon of “surging” at any point in the engine’s normal operating range and thus reduces the possibility of a failure due to a resonance coinciding between the neutral and operational frequencies of the spring in motion. Secondly, the spring mass is considerably lower than that of a coil spring of the dimensions necessary to produce the required tension to close the valve. This allows the torsion arm to follow and react to the valve’s needs more quickly. And lastly, it was found that the overall height of the engine could be kept down if a torsion bar system were used. This is particularly important in a motorcycle which has its oil supply in the crankcase, making it somewhat “tall” to begin with.

The two camshafts are driven by a chain which runs from the crankshaft at half crankshaft speed. Although it is quite long, the chain runs over a series of seven guide rollers to keep the noise down to an unobjectionable level. The valve face and the valve stem ends are stellite-tipped to reduce wear. Valves are set at an included angle of 90 degrees, and the hemispherical combustion chambers and central plug location improve high rpm breathing ability and efficiency.

Cylinders are cast in aluminum alloy as one unit with replaceable special steel alloy sleeves. The cam chain runs in a compartment between the cylinders, and two of the cylinder hold-down studs are hollow to serve as oil return galleries. The inlet rocker cover is baffled on the inside and vents excess crankcase pressure through a line to the atmosphere, reducing the possibility of an oil leak.

Pistons are cast of a low-expansion aluminum alloy and employ a four-step taper to minimize noise and extend engine life. In addition, the wrist-pins are offset 1mm towards the inlet valve because the point of maximum combustion pressure is slightly after top-dead-center, and moving the pin location tends to balance out the pressures and reduce piston slap.

The crankshaft rides in four roller bearings in the horizontally-split crankcase, and is press-fitted together, making a very rigid assembly. Oil passages from the two center main bearings lubricate the needle bearings at the big ends of the rods, and grooves are provided to act as additional oil filters in addition to the centrifugal affair at the right end of the crankshaft, in which spinning blades force impurities to the outside of the filter body. Honda employs a plunger-type oil pump in which two steel balls serve as valves.

One of the best clutches that Honda has built is the seven-plate unit in the CB 450. It takes up the drive smoothly

and positively with a minimum of spring pressure being felt at the clutch lever. Transmission ratios remained unchanged in the K-3 model, and as with the earlier five-speed models, gear spacing is ideal for the power characteristics of the engine. Three shifter forks mesh with the shifting drum which, in turn, rests on ball bearings. Shifting is light and positive, neutral is easy to find and identify with the aid of a green light in the tachometer.

Electrical power is provided by an AC dynamo mounted on the left end of the crankshaft. The AC current is passed through a selenium rectifier to change it to DC to charge the battery, which has to deliver approximately 120 amps when the electric starter is activated. Lights were excellent, the headlight throwing a powerful, wide beam on low and a perfectly-focused high beam. Turn signals operated well and added a reassuring feeling when turning, especially at night. Electrical wiring is neatly placed and of high quality. Horn volume was disappointingly low, however.

Overall finish and detailing is what we’ve come to expect from Honda. Painted surfaces reflect a deep lustre, chrome is excellent and welds are neat and substantial. Noteworthy are the polished aluminum outer cases and valve covers, which are sprayed with a clear lacquer to retard the formation of corrosion. This feature is especially welcomed by those of us who live near the ocean. Also welcomed are the nicely laid-out controls which fit well into hand when they are needed. The left grip contains the turn signal switch and horn button, and the right grip houses the headlight switch, electric starter button and a three-way switch for shorting out the engine in case of trouble. In the middle position, the contacts remain open and the engine runs normally, but flicking the switch either way shorts out the engine, making it unnecessary to grope for the main ignition switch which is located under the left side of the gas tank near the front.

The new CB 450 has another item that was borrowed from the CB 750, which caused mixed feelings among our testers. The gas tank is a smaller version of the unit found on the Four which holds 3.6 gallons as opposed to the Four’s 5.0. Aesthetically pleasing as it is to most of us, one member of the staff complained that it was too wide between his knees, which made him a little nervous while sweeping through a series of switchbacks, where we like to test the roadability of the machines. But this is the price you pay to obtain convenient fuel capacity for more sedate activities like long-distance touring.

Riding the machine was pure delight. A quick stab at the electric starter brought the engine to life, but it was necessary to open the choke quickly to keep the engine from flooding. After a minute or two warm-up, the bike was ready to ride without sputtering and bucking and the real smoothness could be appreciated. Controls fell nicely under hand and foot, and it was not necessary to stretch to perform the required motions. The only complaint we had regarding the controls was the fact that the front brake lever cannot be adjusted, and starts to activate the brake after very little travel. One staff member found this awkward as he has very short fingers, which made it difficult to brake and blip the throttle open at the same time when down shifting.

The steering is a trifle heavy at low speeds, but this feeling disappears once underway, and the bike feels like a good 350 when negotiating a series of turns. Part of this is no doubt due to the fitting of the 19-in. front wheel from the CB 750, as the gyroscopic action is more suited to fairly heavy machines such as the CB 450. The stability is even more apparent when riding double where the solidity was really appreciated. Both intake and exhaust silencing is excellent, and very little power is lost through the glass wool-packed mufflers.

The more-than-ample torque in the mid-speed range was a boon while riding in traffic. Careful design and construction of the automatic spark advance mechanism and spot-on carburetion no doubt had much to do with this impression of good mid-range torque. In actuality, maximum torque is developed at a rather high rpm figure of 7500.

The front suspension was a trifle stiff on the compression stroke initially, but began to free up considerably during the first few hundred miles, and was quite good by the time we returned the bike. No steering damper is fitted, but we never felt the need for one. The rear shocks are three-way adjustable De Carbon units, which feature pressurized nitrogen gas and oil internally to maintain and control damping on both compression and rebound strokes. The swinging arm is made from tubular steel, but has strengthening gussets welded to the area near the pivot bolt. There was no hint of rear suspension flex either solo or riding double, even over unimproved roads.

It was with great reluctance that we returned the CB 450 after our test. Once again we’ve been able to enjoy one of our favorite aspects of motorcycling, road riding, with a truly sporty, trouble-free machine.

HONDA

CB 450

$ 1049

View Full Issue

View Full Issue