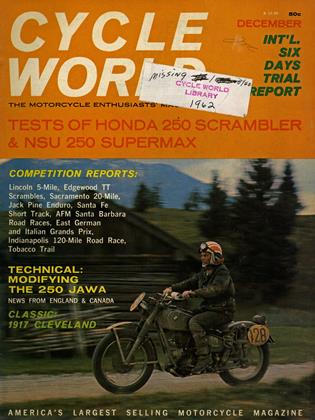

HONDA SCRAMBLER

CYCLE WORLD ROAD TEST

THE HONDA MOTOR CO., LTD., is the most prolific producer of motorcycles the world has ever seen. Hardly a day passes that Honda does not introduce some new model, which must drive the dealers crazy, but is sure to delight the motorcycle enthusiast. Honda has, in the few short years of its existence, turned out motorcycles with engines of 50-, 125-, 150-, 250-, and 305-cubic centimeters displacement. Further, these are offered in several frames, touring, scrambling, trail-riding, road-racing and all-purpose, and in some instances the engine is offered in two stages of tune. Truly, the Japanese factory is a cornucopia of two-wheeled plenty. Our test machine was furnished by Continental Mtrs. in Redondo Beach,California.

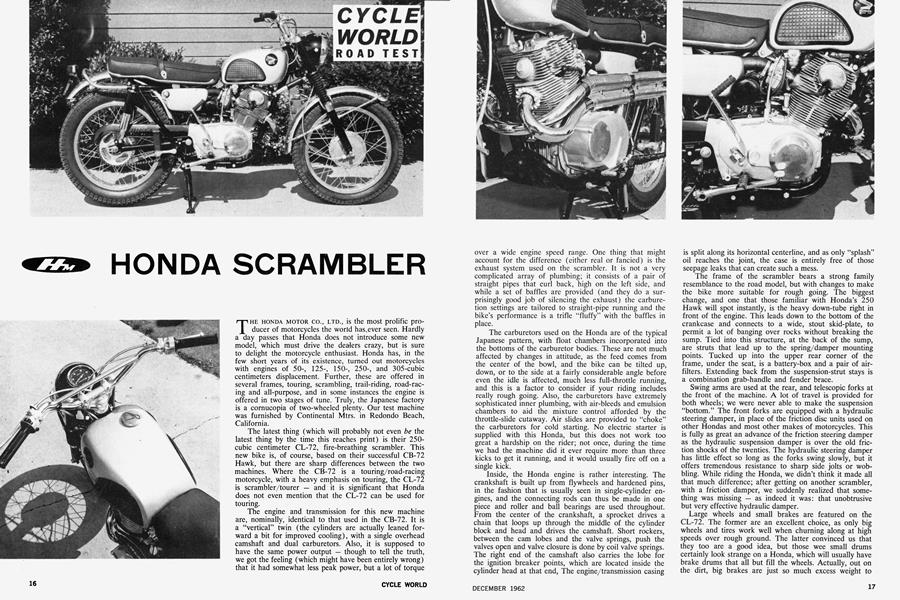

The latest thing (which will probably not even be the latest thing by the time this reaches print) is their 250cubic centimeter CL-72, fire-breathing scrambler. This new bike is, of course, based on their successful CB-72 Hawk, but there are sharp differences between the two machines. Where the CB-72 is a touring/road-racing motorcycle, with a heavy emphasis on touring, the CL-72 is scrambler/tourer — and it is significant that Honda does not even mention that the CL-72 can be used for touring.

The engine and transmission for this new machine are, nominally, identical to that used in the CB-72. It is a “vertical” twin (the cylinders are actually leaned forward a bit for improved cooling), with a single overhead camshaft and dual carburetors. Also, it is supposed to have the same power output — though to tell the truth, we got the feeling (which might have been entirely wrong) that it had somewhat less peak power, but a lot of torque over a wide engine speed range. One thing that might account for the difference (either real or fancied) is the exhaust system used on the scrambler. It is not a very complicated array of plumbing; it consists of a pair of straight pipes that curl back, high on the left side, and while a set of baffles are provided (and they do a surprisingly good job of silencing the exhaust) the carburetion settings are tailored to straight-pipe running and the bike’s performance is a trifle “fluffy” with the baffles in place.

The carburetors used on the Honda are of the typical Japanese pattern, with float chambers incorporated into the bottoms of the carburetor bodies. These are not much affected by changes in attitude, as the feed comes from the center of the bowl, and the bike can be tilted up, down, or to the side at a fairly considerable angle before even the idle is affected, much less full-throttle running, and this is a factor to consider if your riding includes really rough going. Also, the carburetors have extremely sophisticated inner plumbing, with air-bleeds and emulsion chambers to aid the mixture control afforded by the throttle-slide cutaway. Air slides are provided to “choke” the carburetors for cold starting. No electric starter is supplied with this Honda, but this does not work too great a hardship on the rider; not once, during the time we had the machine did it ever require more than three kicks to get it running, and it would usually fire off on a single kick.

Inside, the Honda engine is rather interesting. The crankshaft is built up from flywheels and hardened pins, in the fashion that is usually seen in single-cylinder engines, and the connecting rods can thus be made in one piece and roller and ball bearings are used throughout. From the center of the crankshaft, a sprocket drives a chain that loops up through the middle of the cylinder block and head and drives the camshaft. Short rockers, between the cam lobes and the valve springs, push the valves open and valve closure is done by coil valve springs. The right end of the camshaft also carries the lobe for the ignition breaker points, which are located inside the cylinder head at that end, The engine/transmission casing is split along its horizontal centerline, and as only “splash” oil reaches the joint, the case is entirely free of those seepage leaks that can create such a mess. Large wheels and small brakes are featured on die CL-72. The former are an excellent choice, as only big wheels and tires work well when churning along at high speeds over rough ground. The latter convinced us that they too are a good idea, but those wee small drums certainly look strange on a Honda, which will usually have brake drums that all but fill the wheels. Actually, out on the dirt, big brakes are just so much excess weight to carry around; the wheels don’t get enough of a grip to enable the rider to brake very hard in any case. And, too, the CL-72’s brakes did seem to be adequate during the road riding we did with the bike.

The frame of the scrambler bears a strong family resemblance to the road model, but with changes to make the bike more suitable for rough going. The biggest change, and one that those familiar with Honda’s 250 Hawk will spot instantly, is the heavy down-tube right in front of the engine. This leads down to the bottom of the crankcase and connects to a wide, stout skid-plate, to permit a lot of banging over rocks without breaking the sump. Tied into this structure, at the back of the sump, are struts that lead up to the spring/damper mounting points. Tucked up into the upper rear corner of the frame, under the seat, is a battery-box and a pair of airfilters. Extending back from the suspension-strut stays is a combination grab-handle and fender brace.

Swing arms are used at the rear, and telescopic forks at the front of the machine. A lot of travel is provided for both wheels; we were never able to make the suspension “bottom.” The front forks are equipped with a hydraulic steering damper, in place of the friction disc units used on other Hondas and most other makes of motorcycles. This is fully as great an advance of the friction steering damper as the hydraulic suspension damper is over the old friction shocks of the twenties. The hydraulic steering damper has little effect so long as the forks swing slowly, but it offers tremendous resistance to sharp side jolts or wobbling. While riding the Honda, we didn’t think it made all that much difference; after getting on another scrambler, with a friction damper, we suddenly realized that something was missing — as indeed it was: that unobtrusive but very effective hydraulic damper.

Although it was not intended for touring, the CL-72 can certainly be used for that purpose. Unlike many dirt bikes, it handles quite well on paved surfaces, and it does have lighting and muffling equipment — though this would usually be removed for serious competition. The only complaint we had is that the saddle is not very good. It is short, but is divided into two sections by a grabstrap, as though they had anticipated that one might want to carry a passenger — and an extra set of pegs are provided for this possible passenger. The fact is that the saddle is too short for two people; indeed, it is too something for even one person. The average rider will find that after he gets settled behind the well-placed handlebars and above the equally well-placed folding pegs, the seat’s grabstrap will be right under his behind, and he will be uncomfortably aware of that fact. Mercifully, the grab-strap is easily removable, and with it out of the way the situation is improved. Even so, for this rider the seat is a bit too narrow.

The fit and finish of the CL-72 is a fine example of what we think of as “mass-product careful;” a company like Honda, producing some 85,000 units every month, cannot hand-finish its machines. It can, however, use good materials, good tooling and careful assembly methods, which is done. And, the use of this kind of careful mass-production is the reason for the Honda’s neat and clean appearance, and its very reasonable price.

Out thumping along through the rough, we learned a lot of things about how strong a twin can be under such conditions. The Honda, even though just a 15-incher, comes on with a bang well below the torque peaking speed of 7500 rpm. It will pull strongly almost from idle, and when those rpm do begin to gather, it will really storm along. The situation is helped along, too, by the good, solid-feeling clutch and transmission, which can be abused ferociously without anything showing signs of failure. Before actually trying the bike, we were somewhat of the opinion that it would be necessary to keep the Honda cranked-up constantly, but it proved to have surprising flexibility.

Handling on all surfaces was good, but particularly outstanding was the Honda’s behavior on the more firm dirt and clay. We would imagine that the CL-72 would make a very fine flattrack or TT bike, and it should do well in high-speed scrambles, which are usually run over relatively good surfaces. When the going gets really sloppy, the Honda’s steering was a trifle too quick for our tastes. We learned to live with it, and many riders might prefer the steering just as quick as it is.

We will be interested in seeing what kind of a competition showing this Honda scrambler will make. It has the power, the handling (with the reservations we noted above) and the reliability to do very well. For the real, honest-to-goodness hot-shoe, or the man who wants to develop his talents along fast and furious lines, the Honda CL-72 is mighty fine equipment. •

HONDA

250 CL-72

SPECIFICATIONS

$690

PERFORMANCE

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

The Service Department

December 1962 By Gordon H. Jennings -

Cycle Round Up

December 1962 By Joseph C. Parkhurst -

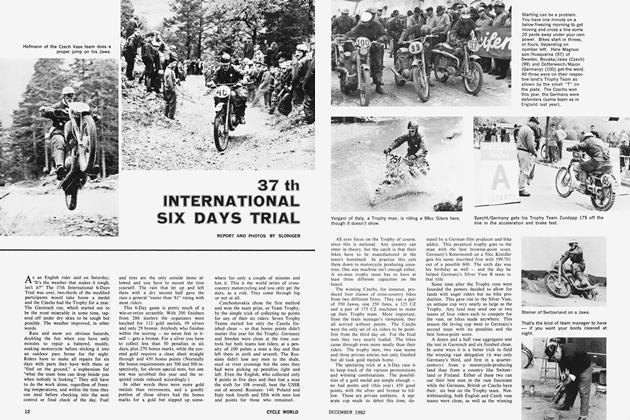

37 Th International Six Days Trial

December 1962 By Sloniger -

Modifying the Jawa 250 For Road Racing

December 1962 -

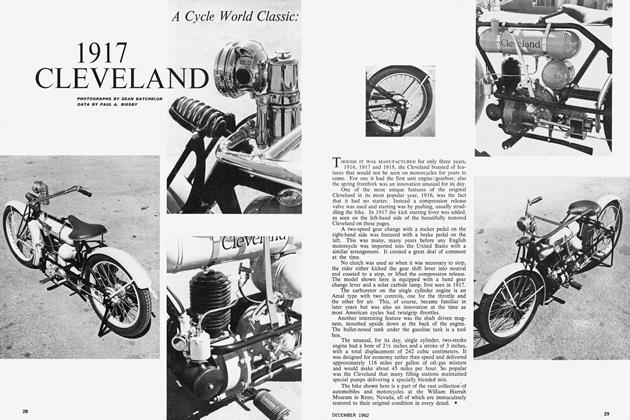

A Cycle World Classic

A Cycle World Classic1917 Cleveland

December 1962 By Paul A. Bigsby -

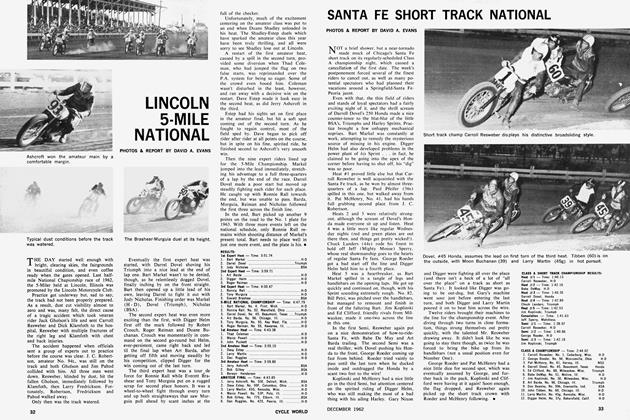

Lincoln 5-Mile National

December 1962 By David A. Evans