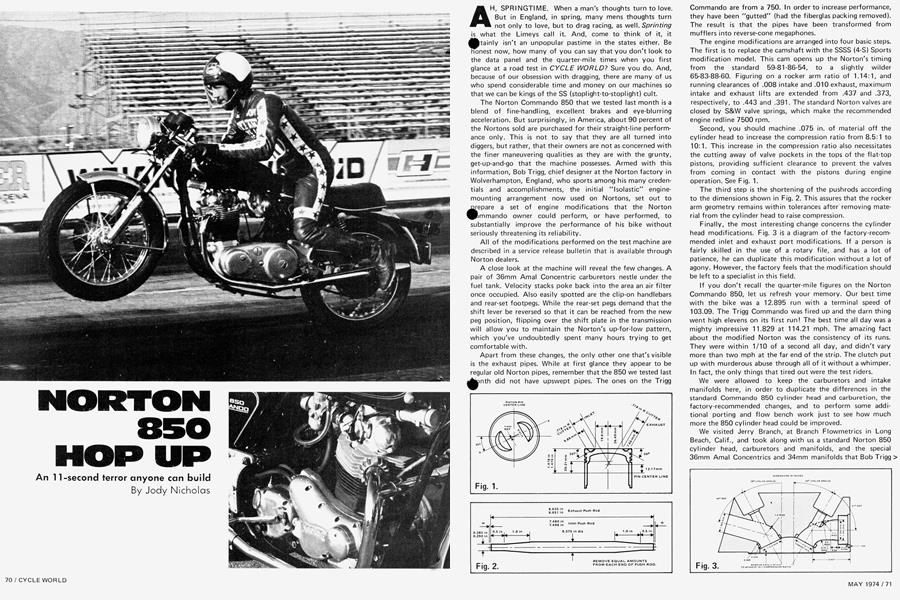

NORTON 850 HOP UP

An 11-second terror anyone can build

Jody Nicholas

AH, SPRINGTIME. When a man's thoughts turn to love. But in England, in spring, many mens thoughts turn not only to love, but to drag racing, as well. Sprinting is what the Limeys call it. And, come to think of it, it tainly isn't an unpopular pastime in the states either. Be honest now, how many of you can say that you don't look to the data panel and the quarter-mile times when you first glance at a road test in CYCLE WORLD? Sure you do. And, because of our obsession with dragging, there are many of us who spend considerable time and money on our machines so that we can be kings of the SS (stoplight-to-stoplight) cult.

The Norton Commando 850 that we tested last month is a blend of fine-handling, excellent brakes and eye-blurring acceleration. But surprisingly, in America, about 90 percent of the Nortons sold are purchased for their straight-line performance only. This is not to say that they are all turned into diggers, but rather, that their owners are not as concerned with the finer maneuvering qualities as they are with the grunty, get-up-and-go that the machine possesses. Armed with this information, Bob Trigg, chief designer at the Norton factory in Wolverhampton, England, who sports among his many credentials and accomplishments, the initial "Isolastic" enginemounting arrangement now used on Nortons, set out to jarepare a set of engine modifications that the Norton ^Pjmmando owner could perform, or have performed, to substantially improve the performance of his bike without seriously threatening its reliability.

All of the modifications performed on the test machine are described in a service release bulletin that is available through Norton dealers.

A close look at the machine will reveal the few changes. A pair of 36mm Amal Concentric carburetors nestle under the fuel tank. Velocity stacks poke back into the area an air filter once occupied. Also easily spotted are the clip-on handlebars and rear-set footpegs. While the rear-set pegs demand that the shift lever be reversed so that it can be reached from the new peg position, flipping over the shift plate in the transmission will allow you to maintain the Norton's up-for-low pattern, which you've undoubtedly spent many hours trying to get comfortable with.

Apart from these changes, the only other one that's visible is the exhaust pipes. While at first glance they appear to be regular old Norton pipes, remember that the 850 we tested last ^^nth did not have upswept pipes. The ones on the Trigg Commando are from a 750. In order to increase performance, they have been "gutted" (had the fiberglas packing removed). The result is that the pipes have been transformed from mufflers into reverse-cone megaphones.

The engine modifications are arranged into four basic steps. The first is to replace the camshaft with the SSSS (4-S) Sports modification model. This cam opens up the Norton's timing from the standard 59-81-86-54, to a slightly wilder 65-83-88-60. Figuring on a rocker arm ratio of 1.14:1, and running clearances of .008 intake and .010 exhaust, maximum intake and exhaust lifts are extended from .437 and .373, respectively, to .443 and .391. The standard Norton valves are closed by S&W valve springs, which make the recommended engine redline 7500 rpm.

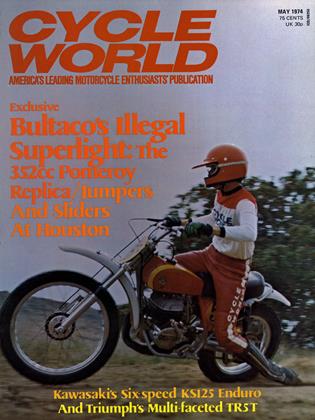

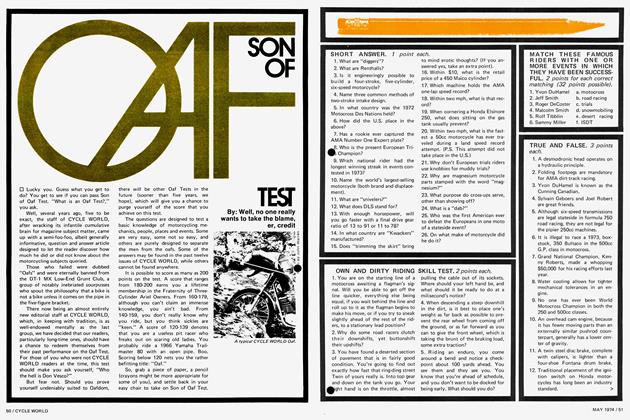

Second, you should machine .075 in. of material off the cylinder head to increase the compression ratio from 8.5:1 to 10:1. This increase in the compression ratio also necessitates the cutting away of valve pockets in the tops of the flat-top pistons, providing sufficient clearance to prevent the valves from coming in contact with the pistons during engine operation. See Fig. 1.

The third step is the shortening of the pushrods according to the dimensions shown in Fig. 2. This assures that the rocker arm geometry remains within tolerances after removing material from the cylinder head to raise compression.

Finally, the most interesting change concerns the cylinder head modifications. Fig. 3 i$ a diagram of the factory-recommended inlet and exhaust port modifications. If a person is fairly skilled in the use of a rotary file, and has a lot of patience, he can duplicate this modification without a lot of agony. However, the factory feels that the modification should be left to a specialist in this field.

If you don't recall the quarter-mile figures on the Norton Commando 850, let us refresh your memory. Our best time with the bike was a 12.895 run with a terminal speed of 103.09. The Trigg Commando was fired up and the darn thing went high elevens on its first run! The best time all day was a mighty impressive 11.829 at 114.21 mph. The amazing fact about the modified Norton was the consistency of its runs. They were within 1/10 of a second all day, and didn't vary more than two mph at the far end of the strip. The clutch put up with murderous abuse through all of it without a whimper. In fact, the only things that tired out were the test riders.

We were allowed to keep the carburetors and intake manifolds here, in order to duplicate the differences in the standard Commando 850 cylinder head and carburetion, the factory-recommended changes, and to perform some additional porting and flow bench work just to see how much more the 850 cylinder head could be improved.

We visited Jerry Branch, at Branch Flowmetrics in Long Beach, Calif., and took along with us a standard Norton 850 cylinder head, carburetors and manifolds, and the special 36mm Amal Concentres and 34mm manifolds that Bob Trigg left with us. Jerry flowed the standard set-up, the factoryrecommended modifications with the 36mm Amal Concentrics, and then flowed the cylinder head to achieve maximum efficiency with his own 34mm Mikuni carburetor modification. Just for reference, here are some additional figures that will be of interest. They compare not only the standard, factory, and Branch Flowmetrics modifications, but some of the other popular and well-known cylinder head/carburetor combinations, as well.

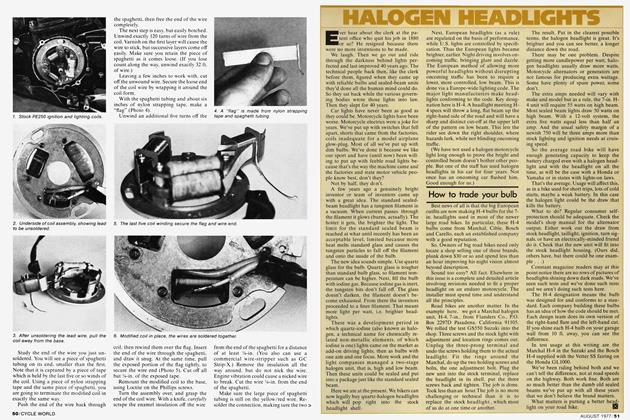

Cu. ft. of air flow per sq.in. of valve area at .425 in. valve lift. 1. Standard Norton, 32mm Amal Concentrics: 46.8 cfm. 2. Factory modification, 36mm Amal Concentrics: 51.4 cfm. 3. Flowmetrics modification, 34mm Mikuni: 56.0 cfm. 4. Flowmetrics modification to Gary Scott's Triumph 750 flat track machine (.390 valve lift): 47.5 cfm.

5. Flowmetrics modification to Warner Riley's HarleyDavidson, 96-cu.-in., fuel-burning Bonneville record holder with a 44mm Mikuni carburetor and .475-in. maximum valve lift: 47.6 cfm.

6. Standard Kawasaki Z-1 with 28mm Mikuni carbureto and .325-in. valve lift: 44.4 cfm.

7. Flowmetrics Kawasaki Z-1 modification, using the standard 28mm Mikunis, which set the records at Daytona in 1973: 54.6 cfm.

8. Harley-Davidson XR-750 racing engine with 36mm Mikuni carburetors at .450 valve lift: 56.8 cfm.

The following charts are labeled and show the standard, factory modification and Branch Flowmetrics modification for the Norton 850 Commando.

No. 1 Standard Norton 850 cylinder head with 32mm Amal carburetors with short (standard) velocity stacks. Max. velocity: 179 ft./sec. at .425 in. valve lift.

No. 2 Norton 850 with factory-recommended porting changes and 36mm 173 ft. /sec. at .425 in. valve lift.

No. 3 Flowmetrics Norton 850 cylinder head modification with 34mm Mikuni carburetors. Max. velocity: 215 ft./sec. at .425 in. valve lift.

No. 1 Standard Norton 850.

No. 2 Factory modification w/36mm Amal carburetor.

No. 3 Flowmetrics modification with 34mm Mikuni carburetor.

This chart gives the air velocity in ft./sec. at the valve seat at all val\^£) lifts. These are complete system checks: carburetor, inlet manifold, cylinder head and inlet valve in place. J5J