THE SOUND TEST

J. G. Krol

ALONG WITH the wonderfulness of his mind and the nobleness of his soul, Big Brother is blessed

with uncanny sensitiveness of his ears which, when perked by a passing twostroke, send neural signals to his Iron Fist, twitching and itching with eagerness, to squash errant bikers...and the manufacturers who supply them with loud exhaust systems.

The brave, raucous sforzandos of banzai pipes will soon echo into final silence as we hum and purr our way into a Quiet New World whose loudest sound may well be the muffled buzz of the cop-chopper circling just over our heads, its xenon spotlight striking down through the night like a bolt from Zeus upon anything louder than a calendar wristwatch. Fortunately, the technology to silence two-stroke expansion chambers has been available for some time and there should be no great difficulty in meeting foreseeable standards.

A pioneer in silenced expansion chambers was J&R Engineering, who advertised the first aftermarket pipes with attached mufflers (CW, Sept. 1965) and the first aftermarket pipes with integral silencers (CW, Dec. 1965). J&R has since changed hands, grown, and split into two companies, one making silencers and the other, expansion chambers—but the old interest in quiet performance is still alive at J&R, and provides a useful checkpoint on the state-of-the-art in this increasingly critical field.

Chuck Kaiser of J&R Expansion Chambers (708 Monroe Way, Placentia, CA 92670) recently ran sound tests on the street pipes he makes for the 500cc Suzuki Twin. These have glass-pak mufflers that have been improved in certain subtle ways from the original Street Sleepers of 1965.

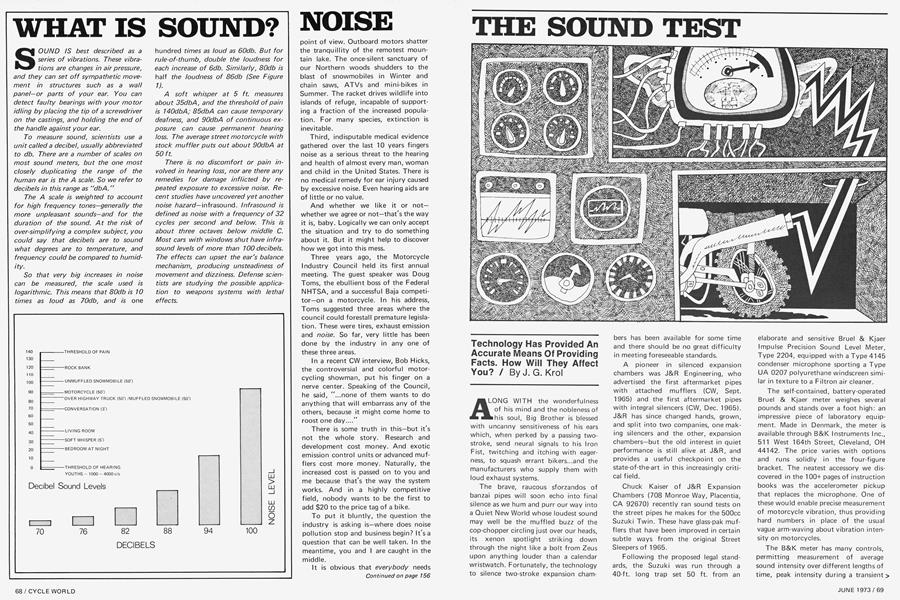

Following the proposed legal standards, the Suzuki was run through a 40-ft. long trap set 50 ft. from an elaborate and sensitive Bruel & Kjaer Impulse Precision Sound Level Meter, Type 2204, equipped with a Type 4145 condenser microphone sporting a Type UA 0207 polyurethane windscreen similar in texture to a Filtron air cleaner.

The self-contained, battery-operated Bruel & Kjaer meter weighes several pounds and stands over a foot high: an impressive piece of laboratory equipment. Made in Denmark, the meter is available through B&K Instruments Inc., 511 West 164th Street, Cleveland, OH 44142. The price varies with options and runs solidly in the four-figure bracket. The neatest accessory we discovered in the 100+ pages of instruction books was the accelerometer pickup that replaces the microphone. One of these would enable precise measurement of motorcycle vibration, thus providing hard numbers in place of the usual vague arm-waving about vibration intensity on motorcycles.

The B&K meter has many controls, permitting measurement of average sound intensity over different lengths of time, peak intensity during a transient > (as when a motorcycle drives by), and even the intensity of a single impulse like a gunshot. The first step is to check meter calibration accuracy, done with a plug-in module that emits a standard sound and should produce a certain db reading on the dial of the meter.

The trick in muffler design is to attenuate the mid-frequencies that are weighted most heavily by the A-scale, the one most closely duplicating the range of the human ear. At 6000 rpm the fundamental frequency of a twostroke engine is 100 cps, and most of the energy is concentrated in the first three harmonics, 200, 400 and 800 cps. Even the fourth harmonic, 1600 cps, is below the peak sensitivity of the Ascale. Therefore, the practical muffler problem is to attenuate the high frequency content of exhaust noise. The low frequency content, falling in the low sensitivity range of the A-scale, is not worth worrying about. The sharp, crackling, rasping noise of an expansion chamber is all the high frequency part of the sound; remove this,, and the remaining rumble sounds much less offensive—and measures much lower on the A-scale.

Fortunately the frequency response characteristics of the Bruel & Kjaer meter are such that no correction need be made for frequencies in the motorcycle-exhaust range. Whether this is true of the meters used by the police, I don't know, and neither will you until somebody challenges a ticket in court.

Corrections for ambient temperature and barometric pressure turned out to be negligible under the test conditions we were operating. With the Orange Freeway just a few yards away, the correction for background noise was carefully checked. The noise from the freeway was about 55db, some 30db under the levels being measured, and this indicated a correction of only a tenth of a db or so, entirely negligible. Flowever, if the CHP sets up sound test stations right on the shoulder of a busy highway, they should make some reduction in the reading of your exhaust to account for the passing traffic.

Another factor that influences readings is the reflectiveness of the surroundings. An open grass field will yield lower readings than, say, an underground parking garage that's all concrete and steel. Since Chuck Kaiser was mainly interested in comparisons, he ran over an asphalt parking lot surrounded on both sides by concrete-walled industrial buildings. These conditions tended to inflate the absolute sound levels measured.

Approaching the 40-ft. trap at 3500 rpm in second gear and cracking full throttle through the trap produced these figures when the Suzuki 500 had its left side toward the meter: Stock exhaust system: 87.5 dbA; J&R power pipe: 89.0 dbA.

The J&R pipe was a bit louder than the stock Suzuki exhaust. On the other hand, when the bike went through the traps with its right side towards the meter, the measurements were: Stock exhaust system: 88.5 dbA; J&R power pipe: 88.5 dbA.

Here the readings were exactly the same. The silenced expansion chamber was exactly as loud as the stock exhaust.

The difference between the left and right sides of the J&R were at least partly due to the fact that the prototype pipes being used had a poorlyfitting fiberglass packing on the left side. The mat had been cut about half an inch short and did not entirely fill the muffler cavity. More interesting is the 1.0 dbA difference between the two sides of the stock exhaust. Were the left and right Suzuki mufflers really different?

Probably not. Repeating the same test conditions several times convinced me that there is no practical way to get the readings more nearly repeatable +/1dbA even under the most ideal conditions. Seemingly slight differences to test rider Claude Pearson in the approach rpm, the throttle opening, and the line through the trap made the measured dbs vary significantly on the sensitive meter. For example, if he approached at the same rpm and rolled full throttle through the trap in different gears, the sound intensity varied by about three-to-one: 1st gear: 91.8 dbA; 2nd gear: 88.5 dbA (as above); 3rd gear: 87.2 dbA.

A difference of 4.6dbA could be the margin between a ticket and a pat on the head. Opening the throttle not quite all the way and not quite as soon as entering the trap seemed to drop the intensity another couple of db.

To get some idea of the harmonic content of the exhaust, we tried the same run on the A-scale and on the linear scale, which weighs all frequencies the same, regardless of how they sound to the normal human ear. Obviously, a good deal of energy was being filtered out by the A-scale since the results were: A-scale: 88.5 dbA (as above, J&R); linear: 95.7 dbA.

A difference of 7.2db means that the bike is producing more than five times as much sound energy as gets counted in the legally specified A-scale. That's a whole bunch but, of course, it is sound energy to which the human ear is not sensitive.

These results indicate that it is entirely possible to produce muffled expansion chambers that are no louder than stock exhaust systems. The J&R pipes for a street Suzuki 500 Twin give their main boost above 4500 rpm and are designed for engines with stock timing or up to a 1 to 2mm raising of the ports. J&R also makes unmuffled racing pipes to the Suzuki Daytona specifications for racing engines with 4mm-raised ports.

But these tests are only the beginning of what will have to be a lengthy effort by all expansion chamber manufacturers, indeed, by manufacturers of stock motorcycles. Once you knock down the noisy exhaust you have to hunt more carefully for the detailed sound-emitters on a bike, first identifying them, then surpressing them.

If you place your hand over the exhaust of an idling two-stroke you'll notice that the walls of the expansion chamber emit a distinctive rattling sound that is quite different from the main exhaust noise. In previous tests on single-cylinder, high-pipe bikes like Yamaha enduros. Chuck Kaiser noted a systematic three or more decibel difference depending on whether the chamber faced toward or away from the meter side of the machine's patch. An improved muffler, per se, can do nothing about sound radiated from the sides of the pipe and chamber, and it may eventually be necessary to go to double-wall construction, or perhaps to coat the exhaust with a tough, temperature-resistant, sound-absorbing plastic.

Many stock exhausts are presently of double-wall construction, but one wonders about their efficiency, i.e., how much quieting they provide per dollar and per pound. The stock Suzuki 500 Twin pipes scaled in at a hefty 19.5 lb.; the replacement J&R expansion chambers had single-wall construction except for the muffler/stinger itself, provided more power, and weighed only 9.25 lb.—less than half the weight of the stock system—and were virtually identical not only in the measured intensity of sound, but also in tone and timbre.

The only possible drawback I could think of with the J&R pipes was that they might blow the glass out in a short time. Some reports have been published suggesting that some, if not all, glass-pak silencers soon lose their stuffing. Indeed, I've examined some brands of bolt-on silencers whose stuffing looked better suited for Angel's Hair decoration on Christmas Trees than for mufflerpacking. Well, there's fiberglass and then there's fiberglass. J&R uses a thick, rolled mat of coarse, flattened strands that is manufactured especially for muffler applications. I very much doubt that these long, matted strands could blow out through the fine holes of the inner stinger-tube; on other mufflers, with fine, short, loose strands of glass and big inner louvers, I very much doubt that the 'glass could stay in. As glass-pak mufflers become more common, longevity will be one of the features buyers will have to look for. Kaiser does not claim that J&R silencers will last forever (neither does an allmetal muffler on a car), but he does claim that neither the cost nor frequency of 'glass replacement will be burdensome to the rider.

Light, durable, effective glass-pak mufflers should soon be stock items with all major expansion chamber manufacturers, but there is still much to be done in moderating motorcycle racket.

First, a considerable amount of practical experience is going to have to be amassed before anyone can say with confidence that a raw number like ''86db'' has any meaning. Extremely sensitive and accurate test instruments are available, true, but the conditions of the test strongly influence the number that shows up on the meter dial. The asphalt and concrete surroundings in which the Suzuki Twin was run undoubtedly gave higher readings than, say, the open, plowed, tree-ringed field just a block down the street. Approach speed, approach rpm, gearing, distance of the bike from the meter, orientation of the bike with respect to the meter and of the meter with respect to the bike...all these add up to as much as half-a-dozen dbs difference in the measurement. It will be interesting to see how wide a tolerance band the police adopt when they begin enforcing silencing laws with their own sound meters.

Second, mufflers are soon going to run into diminishing returns and motorcycle designers are going to have to address themselves to other noise sources: piston slap, bearing rattle,

valve-train clatter, gear and chain whine, tire howl, intake roar, etc. This poses some tough problems, given the traditional design of motorcycles.

A standard way of quieting a noise source is to enclose it; run your car's engine with the hood open and closed and hear the difference. But bikes traditionally have .all the machinery hanging out in the open. Worse, the cooling fins improve the coupling of inner noises to the atmosphere. Try tapping with a screwdriver or small wrench the cooling fins on a bike that has, and another one that does not have, rubber blocks between the fins. Hear how the regular fins ring? Simply draping a heavy blanket over a bike and running it past the meter provides a significant reduction in the measured noise level, demonstrating that an important part of the total sound output is not due to the exhaust, hence not controllable by a muffler.

Continued on page 156

Continued from page 71

And consider how easily you can hear a car that has steel tubing headers in place of the regular cast iron exhaust manifolds...that distinctive rushing sound comes right through the walls of the engine compartment. Yet all motorcycles have steel tubing headers, though some are of tube-within-a-tube construction that should help quiet them down. Happily, anything which is done to reduce energy loss from the walls of the exhaust system—whether as sound or as heat—has the benefit of keeping the exhaust gas energy in a form that can be used for improved exhaust tuning. In principle, you could design a better, more effective expansion chamber using double walls, with insulation between, than the present single-walled types.

Big Brother's campaigns for smog and against safety—or is that the other way round, I can never remember?—add weight, cost, complexity, and failure modes to a vehicle and often work opposite to proven principles of engineering improvement of the machine. At the same time, they accomplish precious little in the way of direct rider benefit, even less when measured in terms of cost/benefit ratio. But his campaign against sound may soon force motorcycle designers to take a hard look at all those irritating rattles, howls, whines and other racket they've been ignoring for decades, and that will seem like a good idea to many riders whose ears now ring for hours after the end of a ride.