FEEDBACK

Readers, as well as those involved in the motorcycle industry, are invited to have their say about motorcycles they own or have owned. Anything is fair game: performance, handling, reliability, service, parts availability, lovability, you name it. Suggestions: be objective, be fair, no wildly emotional but ill-founded invectives; include useful facts like mileage on odometer, time owned, model year, special equipment and accessories bought, etc.

“GLARING FAULTS”

Having ridden motorcycles for 40 years and practiced mechanical engineering for 33, I have some claim to understanding technologies involved. The list of machines I have owned includes the first Crocker 61 ohv ever delivered to a customer and one of the last 600cc shaft-drive Zundapps. Although it is tempting to reminisce, this letter is to discuss two glaring faults of modern motorcycles that were quite visible 65 years ago and remain unabated today—exposed drive chains, and torque reaction with axial-crankshaft engines.

My 1936 Crocker produced an honest 54 bhp at 5800 rpm. It would quite literally tear up asphalt if revvedup and clutched hard (it’s flywheels were fairly heavy). There were no cushioning devices of any kind in the drive line, so the rear chain took the punishing torque peaks of that V-Twin. Chain lubrication was from the engine breather.

My longest ride was from California to New York by way of Yellowstone, Montana, North Dakota and the Michigan Upper Peninsula—close to 4000 miles. This was in 1937, and the Crocker was, in effect, an experimental prototype. I shall spare you the details of my many tribulations en route, but there were no chain problems at all. Whenever road conditions permitted, I cruised at 70+ mph, so that chain was loaded.

Last summer, I rode my Honda CB500 for a 3-day trip in the Sierra Nevadas, spending as much as nine hours in the saddle in one day. My only complaint was the rear chain, which would start kinking and making red dust every 300 miles. The rubber cushions in the rear sprocket and smooth torque of that high-rpm Four made loading much easier for the chain than the 1936 Crocker. Of course 1 could have done better by pre-lubricating as so admirably described by J. Ci. Krol recently in CYCLE WORLD, but that still would not compare with my 1937 experience.

(Continued on page 32)

Continued from page 30

Chains certainly were problems in 1937. (I always carried chain repair tools on long trips.) My basic point is that they are no better in practice today, and we are being blessed with an 82 blip motorcycle with an open rear chain. (Incidentally, I rode aCB750 for a couple of years, and it had more chain problems than the CB500.)

To speculate a bit, it is possible that the heavy breathing action of a V-Twin creates a particularly effective chain lubricant. When smooth-torque engines of high power level appeared, their much-reduced breather oil mist may have led to unexpected trouble. This is no excuse, since the long record of chain service problems in high-powered motorcycles were warning enough.

It is a silly anachronism to have an unenclosed final drive chain on an electric-starting, five-speed, four-cylinder, ohc motorcycle. One has only to examine the detail engineering of the rest of the power plant and transmission to realize that tightly enclosing and splash-oiling the rear chain lies well within current design and production capabilities. However, it is not a simple “bolt-on” proposition, and should be integrated with structure of a swinging arm suspension. The Munch “Mammut” does it, but I want it on my CB500, not a “Mammut.”

H 1 am so anti-chain, why not ride a BMW or Moto Guzzi? This brings us to the second complaint. In 1935 I was riding an Indian “101” Scout behind a buddy on an Indian Four. That four-inline and others like it used a bevel gear set to drive a sprocket from an axially aligned crankshaft. My friend hit an asphalt pothole and became airborne for several feet. With no change in throttle setting, the loss of rear wheel load caused the crankshaft to accelerate. As dictated by Newton’s laws, this caused the entire combination of man and motorcycle to start a barrel roll. When ground was contacted, 30 degrees of that roll had occurred, and promptly became a sliding 90 degrees with ground torce assist. He collected road burns and bruises.

Some 25 years later, riding my Zundapp, I personally repeated the justdescribed maneuver when I unexpectedly hit a shadow-hidden pothole. From knee to sacroiliac I acquired a bruise with colors much-admired by those having access. When another nearmiss of the same nature happened, I decided not to ride motorcycles that are inherently unstable when airborne.

(Continued on page 88)

Continued from page 32

Please note that both torque-reaction accidents occurred with axial crankshafts, and it really does not matter whether the final drive is chain or shaft. The hazard can be computed as engine torque divided by motorcycle rotative inertia about its longitudinal principal axis. Current shaft drive motorcycles (with one important exception) have more hazardous values of this number than the above-mentioned Indian and Zundapp.

The exception is the current MV Augusta Four, which has a transvers^ crankshaft and a shaft drive. This is tl^| only motorcycle since the 1938 Brough Dream which really solves these problems. The Dream did it with two axial crankshafts on a super-posed four-cylinder engine; by rotating the crankshafts in opposite directions, acceleration torque is cancelled. A square Four with axial crankshafts or adding a counterrotating flywheel to current axial-crankshaft engines would accomplish the same result. As a graduate student project in 1939, I designed such a single-crankshaft engine with reversegeared flywheel, and the idea really goes back to Lanchester in 1903.

I have emphasized the hazard involved when airborne as motivating counter-rotating flywheels. Properly designed, they also can make a singlecrankshaft engine as smooth as a square Four. Only persons who have riddo^^ “Squariels” can appreciate the resu^^ which is that cylinder firing pulses and torsional vibration reactions are cancelled.

Too bad only five Brough Dreams were made—George Brough knew he was building a truly vibration-free and torque-neutral power system. Even a square Four has a twice-per-rev vertical vibratory force; the super-posed Four eliminated that. However, vibration and means for its control are a different subject. At least I now can have the quite-acceptable smoothness of my CB500.

Japanese motorcycle engineers have provided mechanical marvels for amazingly low prices—why did they leave the open rear chain as a living and exasperating fossil? And why have their German and Italian counterparts similarly ignored the airborne instabilil^ problem? Plomer J. Wood Sherman Oaks, Calif.

NOT-SO-SUPER RAT

My kid brother-in-law and I bought a new Hodaka Super Rat with the inten-

«n of racing it. According to all that heard or read, Hodakas were fast, good-handling, relatively inexpensive, and as reliable as an anvil.

As planned, my brother-in-law is riding, winning, and on his way to becoming famous; but he’s riding a 250 Maico. The Super Rat? Well, everybody’s entitled to one mistake. We made ours by buying theirs.

Within an hour, the gremlin in the motor appeared. That’s one hour after buying a brand-new bike that’s supposed to be stone reliable. We took it out and rode around easy. The motor died. We took it back to the dealer, who put in a new plug and charged me $1 parts and $1 labor, since it only took him a minute. “Bike isn’t warranteed, ya know.” “Not even for the first hour?” “No tellin’ whatcha mighta done to it.” There was obviously no point in ^^guing with this guy.

The guy at the parts counter was the same way. I came in needing a footpeg rubber, and he acted like I wanted a free motorcycle. Very put out. Well, I took my business elsewhere, and did all of my own trouble-shooting after that. I soon learned that the only way to shoot the trouble in that bike, would be to take a large gun and blow the entire motorcycle to smithereens.

In a year of racing, in which you expect to break a footpeg or bend a handlebar now and then, the Super Rat compiled a record of four finishes in 25 starts. 21 out of 25 times something happened to the engine.

In all fairness, the transmission is flawless, and the forks work well. Added pieces were Girling shocks, after the stock items jammed in the fully jyctended position; wider bars; metal ^Pgs; rebuilt seat; plastic fenders; and a 21 in. front wheel.

Back to the engine, however. There were hundreds of fouled plugs. In addition, we went through two sets of points, 3 condensers and two coils. Then we changed the jetting from 210 to 140, and plug life took a quantum leap from ten minutes to 30 minutes. It went faster, too. In one race (actually two motos with a plug change in between), it took 7th and 9th. Fastest Hodaka there. Honda SLIOOs finished nine out of the top ten, both motos.

Then it was back to the same old game: dozens of plugs; wires; three sets of points; three condensers; two coils; an entire magneto assembly, magnets and all; more plugs; more wires. Then it started to get bad.

Except for three new plugs, the kid ^Äas doing well in a two-hour Marathon, ^htil the bike went out with a frozen ring that resulted in a broken piston. Two weeks later, another piston died the same way. After finishing two motos, another piston went, scoring the cylinder while it was at it.

(Continued on page 90)

Continued from page 88

It couldn’t have been the setting, because the damned thing still turned spark plugs black and gooey. The timing was okay. We’re using the same oil (Bardahl), and the same gas (Mobil), in the Maico, and it still has the original plug.

We really didn’t care what it was. We sold the bike, and the kid who bought it is having trouble making plugs last. We got Hodaka’s boss oinker, and we won’t make the same mistake again. David Miller Milpitas. Calif.

THE $840 LEMON REVISITED

Since w>e received several replies the letter from Paul Lynch regarding his Yamaha RD350 and its 36 sets of plugs (January ’74 CW), we are printing excerpts from those that offered Mr. Lynch advice.— Ed.

We, too, have a Yamaha RD350, and also had a problem with spark plug fouling. We went through 26 plugs! We had the bike into the shop several times and did all of the recommended procedures to try and eliminate the “problem.”

The plug fouling finally stopped when we changed to “low-lead” gasoline. Since we changed over (we’d like to use no-lead, high octane, but can’t get it), we have not had any plugs foul up in the former manner. Edward M. Nelson San Antonio,

I work at a motorcycle shop that sells Honda, Yamaha, and Triumph. I have frequently seen Yamaha 250 and 350 Twin owners come into the shop complaining of basically the same problem that Mr. Lynch has had.

Upon observation of riding habits, we have found that more often than not, they are lugging the engine. The Yamahas are designed to “turn-on”, and beg to be “turned-on.” After very much riding with the tach below the 4500-5000 rpm range, the engine will load-up, causing fouled plugs and other problems.

If the rider will quit worrying about babying the machine and really let it out, using the lower gears for slower speeds, I feel sure that performance will be exciting, pleasing and satisfying. Don KeMp Richmond, Va.

(Continued on page 92)

Continued from page 90

I own a Yamaha RD350, and I also had problems with my plugs. The bike came with NGK B-7HC plugs, which fouled out at 200 miles. I switched to AC plugs, and now have 4400 miles on it with the same plugs and points. Ed Mahaffey Springerville, Ariz.

As an owner of a new Yamaha RD350, I sympathize with Paul Lynch and his 36 sets of plugs. However, I think I might have some tips for him — learned the hard way.

1. Super gas will quickly lead-foul plugs. The owner’s manual says to use low-lead regular of at least 91 octane, and Yamaha seems to mean it. My RD350 now runs like a clock on any brand of regular.

2. At about 800 miles, I discovered that if I shut the throttle slowly, the spring on the oil pump plunger would not return the stroke to its minimum. A single drop of light oil on the plunger allowed it to return, and cured the excess injection of oil, which certainly had not been helping my plugs to stay clean. This at least demonstrates that the pump is leakproof!

3. On my former Yamaha (a YDS3), 1 was able to put the choke on, kick it twice, and let it warm up. Not so on the RD350. I now open the throttle very slightly, put the choke on, kick twice and hold the bike at about 2000 revs for a few seconds before releasing the choke. I then keep it at 2000, and remain ready to put the choke quickly on and off should the bike threaten to die while warming up. Leaving the choke on may foul the plugs.

4. Some general words of advice: I think that anyone who buys a bike should either choose a dealer of known high competence, or have good mechanical instincts himself. My dealer in Marina Del Ray gave me my bike with the timing way off on one cylinder, the point gaps significantly off, the rear tire inflated eight pounds under the minimum recommended pressure, and double the prescribed chain slack. When the bike was returned because it fouled plugs, I watched the mechanic simply raise the cable adjusters on each carb — without even checking the oil pump adjustment. Unless I had great faith in my dealer’s mechanics, Ed check all vital adjustments before the bike left the showroom.

My RD350 now has 2500 miles on it and for the last 1400 miles it has beautifully on one set of plugs. (I have six sets to spare from the previous 1 100 miles). Some people say these bikes “break in” the first 1000 miles and then stop fouling plugs. My guess is that the riders break in, and learn how to treat their machines and iron out the initial dealer maladjustments.

Having learned the hard way, I won’t let my dealer near the bike. It’s easy to tune, I get over 50 mpg with much high-speed and stop-and-go driving. The bike is fast, and after my changing the original dirty light oil in the front forks for S.A.E. 30, it handles beautifully. am very pleased. I just wish that when bought the bike, I knew what I know now. It would have saved a lot of bike-pushing and plug-changing on the Pacific Coast Highway. Robert J. Gladstone Malibu, Cali^

REFLECTIONS ON A BMW

Here are a few impressions of my 1971 R75/5 BMW. It presently has

36,000 miles, 26,000 of which I have personally clicked off. It is equipped with a Windjammer fairing and Craven Comet bags, both of which I’ve enjoyed for the past 10,000 miles.

First it’s good points. It is reliable. It JÄjiuiet. It has no oil leaks. No fuss, no ^Biss. This machine has the ability to cover mile after mile without the necessity of tweaking a nut. That is what makes the bike most enjoyable.

Its power and smoothness, combined with its reliability and the fairing, allow extended 90 mph cruises without worry or fatigue. Extensions for the handlebars allow a more comfortable sitting position with the fairing. Top speed without fairing is a respectable 110 mph.

Everything on the vehicle is made to last, as testified to by the heavy duty cable and wiring. Almost every part can be dismantled with the excellent tool kit supplied. Dealers seem well-stocked with parts, and if they haven’t got what you need, ten days will get it there.

One of the bad points of the vehicle is its suspension. On the straight it is ^^mfortable and solid, although the iront forks don’t absorb sharp bumps effectively. When presented with a series of S-curves or, for that matter, any sudden change in attitude, the suspension doesn’t inspire confidence. It seems to wallow a bit. Also, it is very difficult to get the bike started below 32 degrees. If it’s balow 20, forget it. Ride the Yamaha!

Concerning upkeep and repairs, using ethyl, I get 40 mpg at 70 mph. The rear tire lasts five to eight thousand miles, with Yokohama lasting the longest.

The Metzler front tire lasts 15,000 miles. I’ve had to replace the speedometer module recently for an outrageous $60. I also had to replace one turn signal bulb and a set of points. The battery had a tough time through last winter, so I replaced it with a sturdier and cheaper Honda 750 battery.

(Continued on page 94)

Continued from page 92

BMW oil and air filters can get to be expensive, so I’ve been using other available brands at half the cost. Minor repair on the transmission cost $25, and a voltage rectifier had to be replaced at a cost ot $23. Mark P. Lorenz

Iowa City, Iowa

ONE IN A MILLION

As the owner of a 1972 Kawasaki Trail Boss for nine months and 5500 miles, I feel that I should say a few things about this bike.

I bought the bike when it was three months old and had 2100 miles on the speedo. About a week before I bought it, it had been rebuilt because the circlip dropped out of the piston and destroyed a good part of the engine. This was fixed under warranty, and I was informed by Kawasaki Columbus that it was a one-in-a-million occurrence and wouldn’t happen again.

Well, after 2100 more miles on the speedo, it did happen again. Once again the dealer told me it was a freak accident —one chance in a million. I guess it was just my luck—two out of two million. Naturally, it was fixed again, but this time at my expense.

Next, a hole burned through the pipe wall, and I was told that I’d need a new one. This also just happened to be one of those freak accidents. A stock pipe cost $36.50, so I decided to go to a Hooker Expansion Chamber. This was a definite mistake. It gave me total power at 6500 rpm, and no power after 6750.

The metal stop underneath the steering head broke next, and two huge dents from the handlebars appeared on an otherwise unblemished tank. The dealer wanted $30 to weld a piece back on there, so I told him to forget it.

The bike wasn’t all bad though. Its ten-speed transmission makes it a nice hill climber, but gives it a top speed of about 40 mph in low range. The brakes were good, but the rear would fade after continued hard use.

Suspension was pretty lousy for anybody over 120 lb. Also, the front fender is way too short, allowing mud to cake on the cylinder head and your forehead at the same time.

In all, the bike’s performance was good for a small trail bike, but its unreliability, coupled with lousy dealer service, are things to be considered before buying a bike of this sort. Mike Reed Columbus, Ohio

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsUp Front

April 1974 -

Letters

LettersLetters

April 1974 -

Departments

DepartmentsRound Up

April 1974 By Joe Parkhurst -

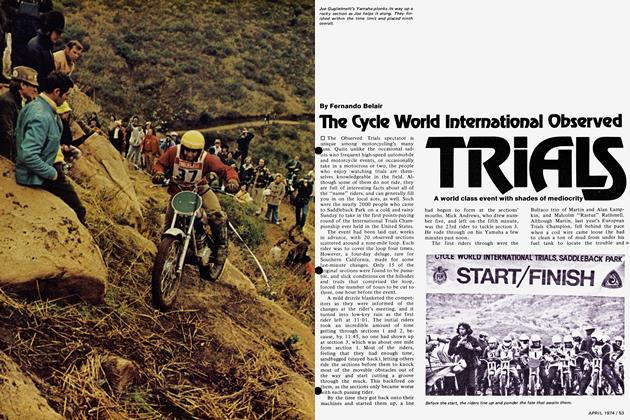

Competition

CompetitionThe Cycle World International Observed Trials

April 1974 By Fernando Belair -

Features

FeaturesThey're Opening Up Land In Utah

April 1974 By John D. Ulrich -

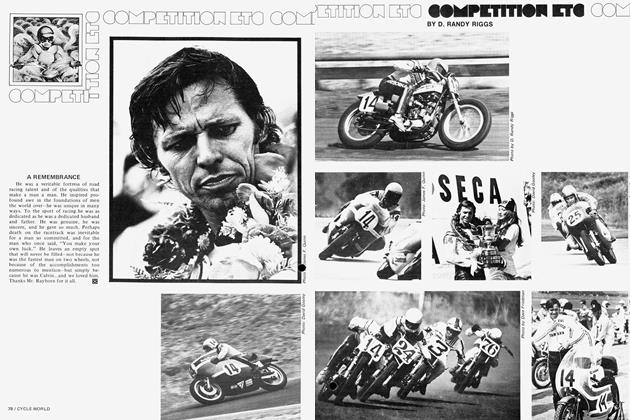

Departments

DepartmentsCompetition Etc

April 1974 By D. Randy Riggs