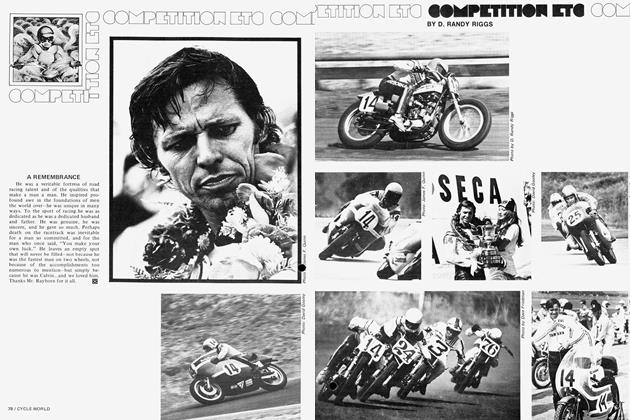

The Cycle World International Observed TRIALS

A world class event with shades of mediocrity

Fernando Belair

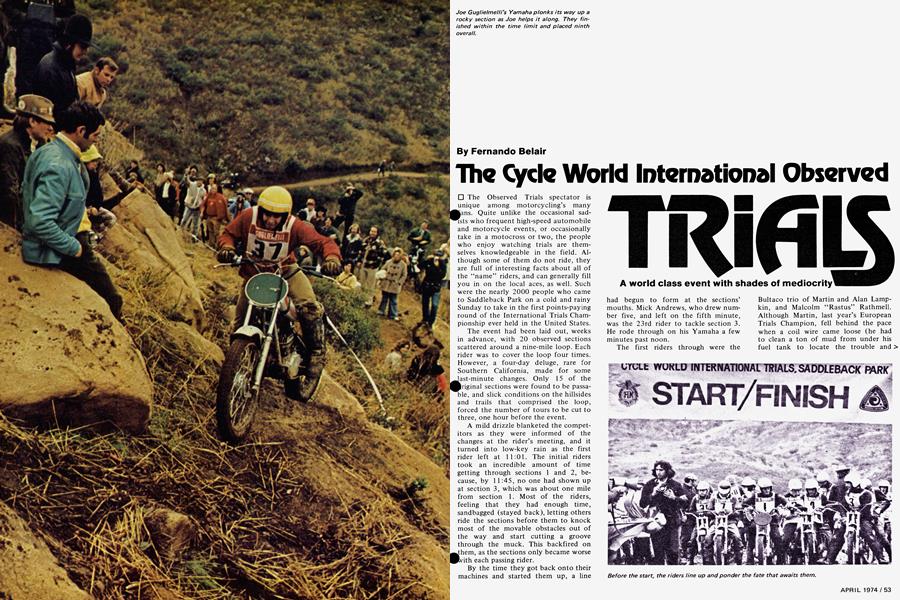

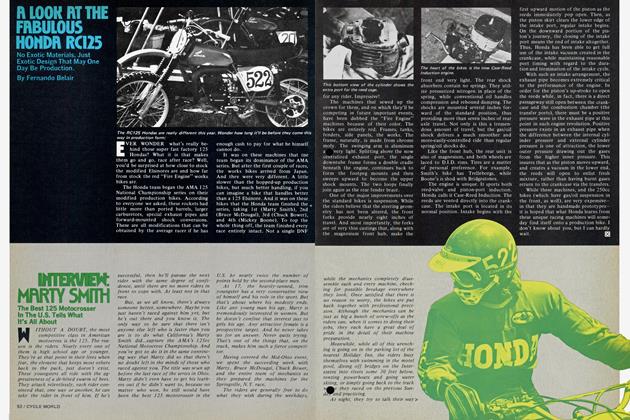

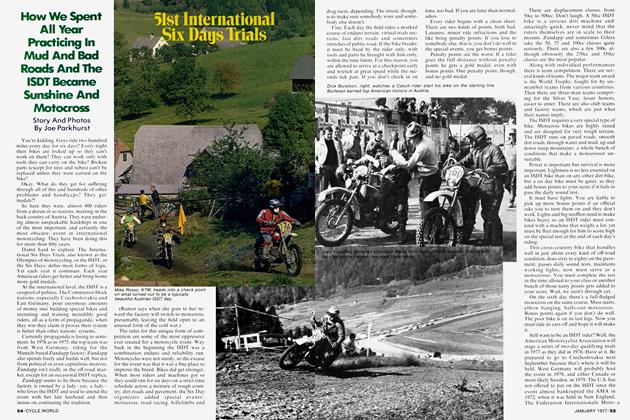

The Observed Trials spectator is unique among motorcycling’s many fans. Quite unlike the occasional sadists who frequent high-speed automobile and motorcycle events, or occasionally take in a motocross or two, the people who enjoy watching trials are themselves knowledgeable in the field. Although some of them do not ride, they are full of interesting facts about all of the “name” riders, and can generally fill you in on the local aces, as well. Such were the nearly 2000 people who came to Saddleback Park on a cold and rainy Sunday to take in the first points-paying round of the International Trials Championship ever held in the United States.

The event had been laid out, weeks in advance, with 20 observed sections scattered around a nine-mile loop. Each rider was to cover the loop four times. However, a four-day deluge, rare for Southern California, made for some

ëast-minute ¡[riginal sections changes. were found Only to 15 be of passathe ble, and slick conditions on the hillsides and trails that comprised the loop, forced the number of tours to be cut to three, one hour before the event.

A mild drizzle blanketed the competitors as they were informed of the changes at the rider’s meeting, and it turned into low-key rain as the first rider left at 11:01. The initial riders took an incredible amount of time getting through sections 1 and 2, because, by 11:45, no one had shown up at section 3, which was about one mile from section 1. Most of the riders, feeling that they had enough time, sandbagged (stayed back), letting others ride the sections before them to knock most of the movable obstacles out of the way and start cutting a groove through the muck. This backfired on

them, as the sections only became worse with each passing rider.

By the time they got back onto their machines and started them up, a line had begun to form at the sections’ mouths. Mick Andrews, who drew number five, and left on the fifth minute, was the 23rd rider to tackle section 3. He rode through on his Yamaha a few minutes past noon.

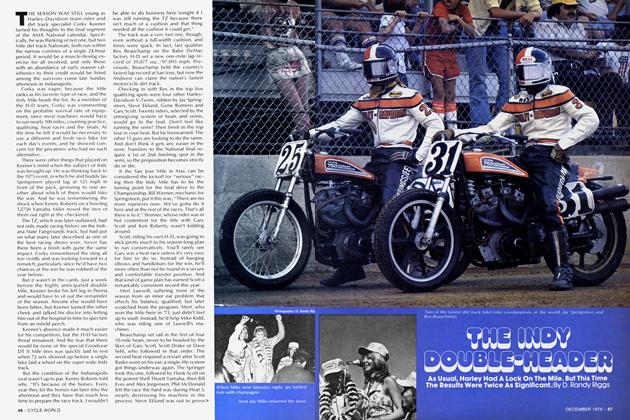

The first riders through were the Bultaco trio of Martin and Alan Lampkin, and Malcolm “Rastus” Rathmell. Although Martin, last year’s European Trials Champion, fell behind the pace when a coil wire came loose (he had to clean a ton of mud from under his fuel tank to locate the trouble and repair it), the “hurry-up” attitude of the other two Britons helped earn them the first two places overall. However, points amassed on observation would only be k)f use to them if they finished within *he allotted five-hour time limit. They sensed that the time schedule would make it tight, so they spent less time looking over sections than they normally would, and rode on doggedly.

By the start of the second loop, the rain had stopped, and good old Sol had broken through. American Lane Leavitt said that if the sun began drying things out, he envisioned several Europeans finishing the second loop “clean” (with no marks lost). Unfortunately, the sun only lasted a half hour, and then it began raining lightly again. The trail between sections was becoming more slippery with every passing moment. Several sections became nearly impassable. Sections 10 and 11 created such a bottleneck that they had to be scratched from the event in order to keep things flowing at a smoother pace. It About the time that most riders were finishing their second loop, it began to rain much harder. The loop was quite treacherous in places, forcing many riders to lay down their bikes and slide down the slick hillsides. At the bottom, many had to restart their mounts in order to continue. Quipped one rider, “I lost more points between sections on the third loop than I did all trials.”

Time was becoming critical now, and many riders literally motocrossed several sections, footing with reckless abandon, just to get through and on to the next one. In the end, only twelve riders finished within the time limit. These competitors were within the “grace period,” and would lose points on time, as well as on observation, but no one finished the event before tardiness points began being awarded.

That’s how tight the time limit was; |bven with the extra hour’s extension that was granted when the heavier rains came. Had this additional time not been granted, there would have been only one finisher: Steve Graham, a Southern California Master who rides a Yamaha TY 250. As it was, Steve had to settle for 8th, which is by far the highest finish by an American in a Championship Round.

Throughout the day’s contest, there were some incredible individual performances. After Martin Lampkin had taken a pair of fives on double-sections 16 and 17, Richard Sunter finessed and balanced his way through, dropping only a single mark in each. Undeniably the most inspiring ride of the day. Richard’s prototype 250 Kawasaki responded willingly to every move that its master made, cresting the mud-covered rock-step section with power to spare.

Bob Nickelsen came down from Colorado with his little 125 Honda, and finished tenth overall. This netted the > bushy-faced bogwheeler his first Championship Point towards the World Title.

Bob’s was the only machine under 250cc to finish the day on time, although, to be honest, Bob’s bike wasn’t really a 125. Bob brought several engines with him from Colorado. He managed to break his 185cc thumper on Saturday. He then put into his frame a 160cc torquer that was reported to have even more “grunt” than his larger engine. Had this engine also gone sour, he had a “milder” 155cc experimental mill waiting to be tried.

Somewhat unknown to many of the spectators, Finland’s Yrjo Vesterinen, and Frenchman Charles Coutard, displayed exceptional ability, finishing the event in 3rd and 4th place, respectively. Both riders scored identically on observation, but the time made the difference.

Felix Krahnstover (the “Gentle Giant”), a 6 ft. 7 in. German who rides a Montesa Cota, managed one of the few clean rides through both sections 18 and 19. These double-sections were taking points from just about everybody. Section 18 was easy enough, but riding it left you on a poor line for 19. Krahnstover attacked 19 like a madman. When he came to the angled rock-step that had stopped more than one International star, he clamped his ankles to the side cases of his machine and literally lifted it over with a quick jumping move.

Malcolm Rathmell turned in the best performance for a single loop when he dropped a mere 12 marks on his second go-round. This feat was equalled by Montesa’s British ace, Rob Edwards; but Rob, too, was bitten by the time limit. Bitten hard, in fact, because, had Rob been able to finish within the time limit, his score of 73 marks lost on observation would have given him the event over Lampkin.

An event of the magnitude of the Cycle World International Observed Trials, is not without problems, however. There were some upset riders who complained about both the observers and the difficult time limit. Three individual riders from the Montesa team filed formal protests, but they were disallowed by the F'IM jury. Overall, the majority of the riders felt that they had enjoyed the event-rain or no rain.

RESULTS

Editorial note: Several people deserve special mention for fine effon put forth in conjunction with this even Vic Conaway laid out some exceptional observed sections, and did a fine job of last-minute reorganization to save the event. The timing of the riders was accurate and without fault, but the time limit was questionable. More on that later.

CYCLE WORLD’S own Ivan Wagar spent many hours hassling with the innumerable technicalities and details that a Trials Coordinator must if as many nations are to be represented as were at this event.

Due to the rains we received during the week prior to the event, Saddleback Park’s main entrance had to be shut down. Vic Wilson, park director, was able to open up an ancient rear entrance to the park so that there would be suitable parking for competitors, press and spectators.

Chief Nelson of the Badgers Police^) Motorcycle Club, a recreational group made up of policemen and their families, is to be congratulated for the effort that his people put forth for the trials.

Now, apart from the nice things that happened at the trials, there were a couple of things which I, as a former trials competitor, found to be discomforting.

Although it was a fine gesture to have as many areas of the U.S. as possible represented, many riders were simply outclassed by the International caliber entries. These less-experienced riders struggled along, trying their hearts out, but mainly getting in the way of riders whose livelihood depends a , deal on their performances in these rounds.

Many of the five observing schools , during the weeks before the event, but they had not had any on-the-job experience. The riders ’ remarks concerning the quality of observers ranged from “soso” to Malcolm RathmelTs “diabolical and he ended up in second place.

While there were the usual number of questionable calls, the observers were

not in unison as to whether or not a rider could break the imaginary line between two outside markers. Some were allowing it, while others would not. This controversy caused section 8 to be thrown out on the first loop. To some riders, it was a relief to receive news, but others watched performances go down the drain.

Not only were the observers confused, but so were the riders. Since there is no established universal rule (such as one dab costs you one point), regarding the imaginary line in question, the riders were banking on an explicit explanation in the supplementary rules to clear up the situation. But all that the rules said was that a failure (5 points) “will be deemed to have occurred when: ...any wheel of the machine crosses an artificial boundary. ”

(Continued on page 85)

Continued from page 56

Now, did this mean that if a wheel broke the line, without crossing it completely, a five would be awarded? Or could the rider break the line as long as a portion of his wheel was within the section? Also, how about riding directly on the line with half of the rider and machine outside the section and the other half in? With many tight turns to contend with, the riders wanted as much room as they could legally use. Yet the answers they got to their questions did not coincide with what the observers were docking them for.

The question also came up concerning exactly what constituted a failure for stopping forward motion within a section. The rules stated that, “a failure will be deemed to have occurred when: ...the machine ceases to move in a forward direction relative to the course. ’’ Period. This meant that riders had to maintain forward motion at all times, and that they could not stop in the middle of a section, balance themselves with their feet still up on the pegs, correct their position relative to the line they had selected to take through the section, and then continue.

Although not a popular rule, at least this one was clear and explicit. Why then were observers allowing riders to do exactly what I have detailed above? Clearly, the observers had not seen the rule so explicitly stated. And what of the riders? What about the many who, not knowing that the observers were not following the written rules, took points for dabbing which, had they stopped and corrected their position, they might not have incurred? With the spread between 2nd and 4th places at less than three points, 7th and 8th less than two and 9th and 10th less than one, any combination of riders, either following the rule as written or not following it, could have drastically altered the standings.

There were some conflicting reports about sections 10 and 11. One report said that the riders were told that they couldn’t ride sections 10 and 11 on their second loop until everyone on their first loop had passed through. The reason for this was that the sections were to be altered because they were, in their present state, too difficult and creating a massive bottleneck. Then, when the last of the first-loop riders had passed through, the section was closed down, costing the riders who had waited, considerable time. The trials organizers granted a one-hour extension on the time limit, but some riders were claiming that they had lost too much time in the mix-up.

(Continued on page 86)

Continued from page 85

The other report said that several Europeans and top Americans banned together and stalled the trials at these sections. This was reportedly done in order to have the sections eliminated from the event (which they were), and also to have the time limit lifted (which it was not). If the first report can proven accurate, then the entire evexj may be discarded, and the FIM points awarded the riders negated. But, if the second story is the more accurate, then the riders slit their own throats.

More trouble at sections 3 and 4. The observer situated atop section 3 was not equipped with a puncher to mark the riders’ scorecards, so the section 4 observer had to keep track of and mark the points lost by the riders in both sections 3 and 4. Thus, when the riders began riding section 4, the observer had to score them, mark their score for section 4, look on his clipboard for their score on section 3, and punch their card for that section. Meanwhile, he also had to keep an eye on the observer atop section 3, who was flashing the scores of riders just now riding that section. Confusion reigned, and many riders couldn’t believe what they saw haM^ pening. Fortunately, the people wl^F were observing at these sections were good observers and they, although arguing with each other, managed to satisfy a majority of the riders.

If there is a Trials next year, let’s hope that people with more trials experience will have the positions of authority, such as observers and course marshals. I understand that the Badgers have now taken up trials riding (on their desert and enduro bikes, of course), and the first-hand experience will make their help extremely valuable next year.

Some of the European events have as many or more hassles than we had with ours. But we were on trial this time. We had to put our best foot forward (no pun intended). Let’s hope that the FIM recognizes all of the fine people who put out so much energy for this fine cause, and that a trials will become pa of the U.S.’s International competitions calendar next year and in the years to come. —Fernando Belair