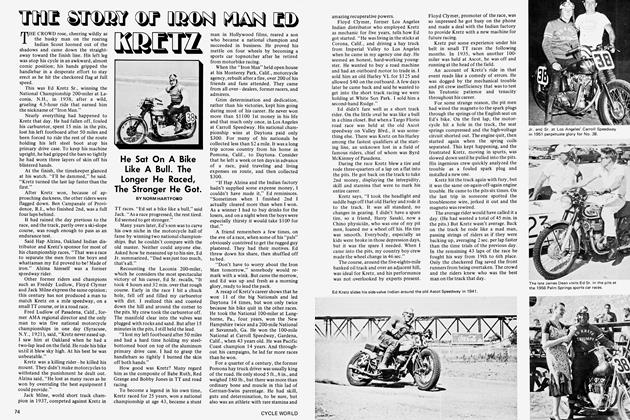

PERSONALITY: Joe Petrali

Winner Of More Nationals Than Anyone In History

Norm Hartford

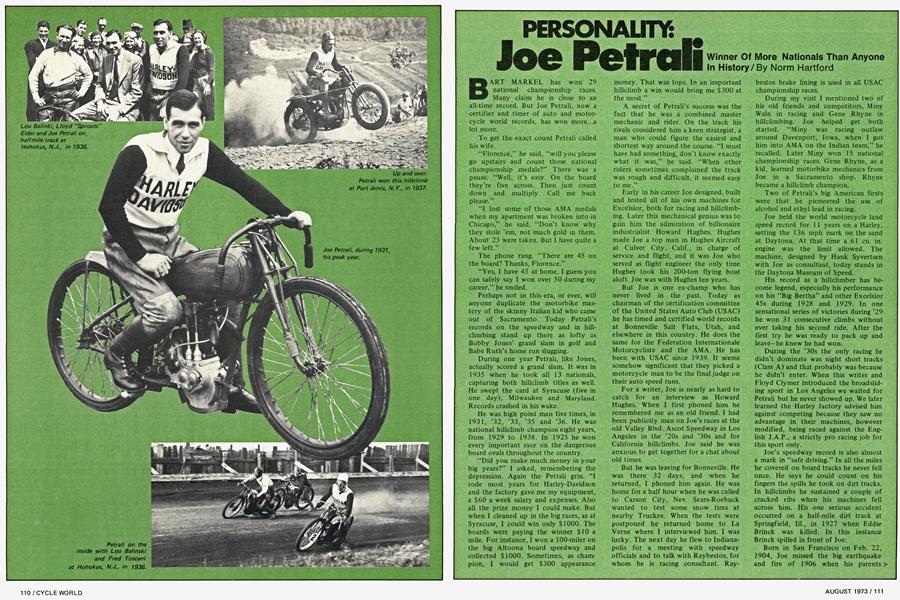

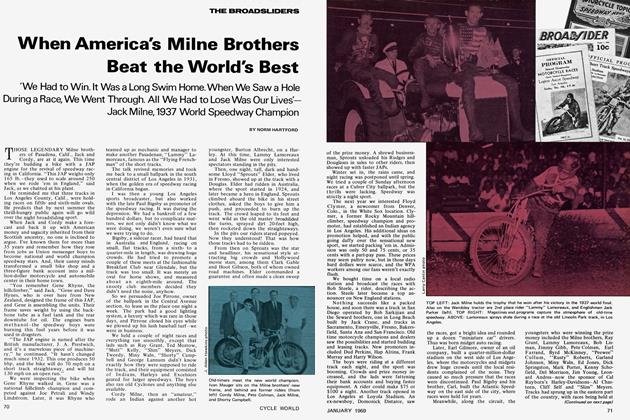

BART MARKEL has won 29 national championship races. Many claim he is close to an all-time record. But Joe Petrali, now a certifier and timer of auto and motorcycle world records, has won more...a lot more.

To get the exact count Petrali called his wife.

“Florence,” he said, “will you please go upstairs and count those national championship medals?” There was a pause. “Well, it’s easy. On the board they’re five across. Then just count down and multiply. Call me back please.”

“I lost some of those AMA medals when my apartment was broken into in Chicago,” he said. “Don’t know why they stole ’em, not much gold in them. About 23 were taken. But I have quite a few left.”

The phone rang. “There are 45 on the board? Thanks, Florence.”

“Yes, I have 45 at home. I guess you can safely say I won over 50 during my career,” he smiled.

Perhaps not in this era, or ever, will anyone duplicate the motorbike mastery of the skinny Italian kid who came out of Sacramento. Today Petrali’s records on the speedway and in hillclimbing stand up there as lofty as Bobby Jones’ grand slam in golf and Babe Ruth’s home run slugging.

During one year Petrali, like Jones, actually scored a grand slam. It was in 1935 when he took all 13 nationals, capturing both hillclimb titles as well. He swept the card at Syracuse (five in one day), Milwaukee and Maryland. Records crashed in his wake.

He was high point man five times, in 1931, ’32, ’33, ’35 and ’36. He was national hillclimb champion eight years, from 1929 to 1938. In 1925 he won every important race on the dangerous board ovals throughout the country.

“Did you make much money in your big years?” I asked, remembering the depression. Again the Petrali grin. “I rode most years for Harley-Davidson and the factory gave me my equipment, a $60 a week salary and expenses. Also all the prize money I could make. But when I cleaned up in the big races, as at Syracuse, I could win only $1000. The boards were paying the winner $10 a mile. For instance, I won a 100-miler on the big Altoona board speedway and collected $1000. Sometimes, as champion, I would get $300 appearance money. That was tops. In an important hillclimb a win would bring me $300 at the most.”

A secret of Petrali’s success was the fact that he was a combined master mechanic and rider. On the track his rivals considered him a keen strategist, a man who could figure the easiest and shortest way around the course. “I must have had something, don’t know exactly what it was,” he said. “When other riders sometimes complained the track was rough and difficult, it seemed easy to me.”

Early in his career Joe designed, built and tested all of his own machines for Excelsior, both for racing and hillclimbing. Later this mechanical genius was to gain him the admiration of billionaire industrialist Howard Hughes. Hughes made Joe a top man in Hughes Aircraft at Culver City, Calif., in charge of service and flight, and it was Joe who served as flight engineer the only time Hughes took his 200-ton flying boat aloft. Joe was with Hughes ten years.

But Joe is one ex-champ who has never lived in the past. Today as chairman of the certification committee of the United States Auto Club (USAC) he has timed and certified world records at Bonneville Salt Flats, Utah, and elsewhere in this country. He does the same for the Federation Internationale Motorcycliste and the AMA. He has been with USAC since 1939. It seems somehow significant that they picked a motorcycle man to be the final judge on their auto speed runs.

For a writer, Joe is nearly as hard to catch for an interview as Howard Hughes. When I first phoned him he remembered me as an old friend. I had been publicity man on Joe’s races at the old Valley Blvd. Ascot Speedway in Los Angeles in the ’20s and ’30s and for California hillclimbs. Joe said he was anxious to get together for a chat about old times.

But he was leaving for Bonneville. He was there 32 days, and when he returned, I phoned him again. He was home for a half hour when he was called to Carson City, Nev. Sears-Roebuck wanted to test some snow tires at nearby Truckee. When the tests were postponed he returned home to La Verne where I interviewed him. I was lucky. The next day he flew to Indianapolis for a meeting with speedway officials and to talk with Raybestos, for whom he is racing consultant. Raybestos brake lining is used in all USAC championship races.

During my visit I mentioned two of his old friends and competitors, Miny Wain in racing and Gene Rhyne in hillclimbing. Joe helped get both started. “Miny was racing outlaw around Davenport, Iowa, when I got him into AMA on the Indian team,” he recalled. Later Miny won 15 national championship races. Gene Rhyne, as a kid, learned motorbike mechanics from Joe in a Sacramento shop. Rhyne became a hillclimb champion.

Two of Petrali’s big American firsts were that he pioneered the use of alcohol and ethyl lead in racing.

Joe held the world motorcycle land speed record for 11 years on a Harley, setting the 136 mph mark on the sand at Daytona. At that time a 61 cu. in. engine was the limit allowed. The machine, designed by Hank Syvertsen with Joe as consultant, today stands in the Daytona Museum of Speed.

His record as a hillclimber has become legend, especially his performance on his “Big Bertha” and other Excelsior 45s during 1928 and 1929. In one sensational series of victories during ’29 he won 31 consecutive climbs without ever taking his second ride. After the first try he was ready to pack up and leave—he knew he had won.

During the ’30s the only racing he didn’t dominate was night short tracks (Class A) and that probably was because he didn’t enter. When this writer and Floyd Clymer introduced the broadsliding sport in Los Angeles we waited for Petrali but he never showed up. We later learned the Harley factory advised him against competing because they saw no advantage in their machines, however modified, being raced against the English J.A.P., a strictly pro racing job for this sport only.

Joe’s speedway record is also almost a mark in “safe driving.” In all the miles he covered on board tracks he never fell once. He says he could count on his fingers the spills he took on dirt tracks.

In hillclimbs he sustained a couple of cracked ribs when his machines fell across him. His one serious accident occurred on a half-mile dirt track at Springfield, 111., in 1927 when Eddie Brinck was killed. In this instance Brinck spilled in front of Joe.

Born in San Francisco on Feb. 22, 1904, Joe missed the big earthquake and fire of 1906 when his parents moved to Sacramento a few months in advance of the disaster.

It was the gradual end of the horse and buggy age with cars and motorcycles appearing in increasing numbers. Joe was only seven years old when he attached himself to a neighbor, Dewey Houghton, a mechanic who owned a 30.50 belt drive Flanders Four.

“Houghton let me clean and shine up his bike,” recalls Joe. “I became fascinated with the mechanism. He also took me to the Sacramento Fairgrounds to see Don Johns and other cycle champs of those days.”

At the age of 12, Joe soloed for the first time on Houghton’s bike. At 13 his father succumbed to his coaxing and bought him a used Hedstrom 30.50 Indian. “I took it apart and put it back together more than I rode it,” he recalls.

Then he went to work for Archie Rife, a Sacramento Indian dealer. He was a skinny kid of 13, but Rife recognized his mechanical know-how and gave him a free hand. On the side Joe converted his Indian for racing. He was 14 years of age when he won his first event of importance, an economy run in Sacramento. Covering 176 miles on a gallon of gas on his lunger, he set a national record for that year.

Racing in Northern California outlaw meets, he finally attracted the attention of Jud Carriker, who bossed the West Coast factory Indians. Carriker wanted to give the eager kid a chance, but there was no fast bike available. Then word came that Shrimp Burns had been killed at Toledo. Carriker told Joe he could ride Burns’ Indian on the steeply banked board speedway at Fresno. It was 1920.

“I was 16 years old and in shock when I realized I was up against the giants of racing, the Harley big five of Ray Weishaar, Ralph Hepburn, Otto Walker, Fred Ludlow and Jim Davis. Also, Indian’s Gene Walker and Excelsior’s Paul Anderson.” To complicate matters Carriker decided to test out alcohol as a fuel for the first time in this meet.

“Using the alcohol we didn’t have the right carburetion. My engine would shoot out with a burst of speed, then sputter. The Harley team was uneasy and boxed me in. But I finally broke loose and took a 2nd place that day. It gave me added confidence. After that race I went to work for AÍ Crocker, an Indian dealer in Kansas City, as mechanic,” Joe said.

His next big race, the one that made him, was at Altoona on the boards. “In this race I chased the man behind me,” he laughed. At the last minute at Altoona the Indian promised him got sidetracked to Pittsburg and did not arrive. Then Ralph Hepburn spilled on his Harley when it froze up during practice and he suffered a broken hand.

"Hepburn offered me the bike on a 50-50 split of the prize money and I grabbed at the chance," said Joe. "The engine kept overheating but I fixed that. Then I tried some tetraethyl lead that Eddie Brinck had picked up at the Wright Field experimental aviation sta tion in Dayton, Ohio. The other riders shied away from the ethyl but I figured I had nothing to lose. The engine clicked perfectly.”

(Continued on page 126)

Continued from page 112

When the 100-miler started, Jim Davis flew away to a commanding lead and threatened to lap the field. When Davis dropped a valve and went to the pits, Joe figured the leader and the man to beat was Eddie Brinck. What he didn’t know was that Brinck had gone to the pits for a couple of laps. So when Brinck passed him, Joe pursued madly. At the same time Joe noticed that Ralph Hepburn, started signaling for him to slow down. It didn’t make sense. Then the entire pit crew began waving for him to slow up. When Joe and Brinck hit the checkered flag with Brinck in front, Joe assumed that Brinck had won. But Joe figured he had a chance for second money and kept going. Then he noticed that his pit crew had stopped waving and were slapping each other on the back. Joe turned extra laps just to make sure he had finished. When he came around the last time the officials were holding up a sign that read “Stop.” So Joe, exhausted, pulled into the pits. He collapsed in a heap.

When he regained his breath he said to Hepburn, “Why did you stop me? I had a chance for second money.” Hepburn answered, “Boy, you won the race.” Joe had turned the 100 miles in the then amazing time of 59:47.2 —less than an hour.

Harley Davidson wanted to sign this sensational young newcomer who had beaten the greatest, such as Brinck, Davis, Curley Fredericks, Johnny Bodnar, Bill Minnick, Johnny Krieger, Johnny Seymour and Bob SirKegian. But nobody seemed to know where Petrali had gone. The factory finally located him at Crocker’s Kansas City shop, mending machines. Harley signed him to a contract on the spot. Then Joe went out in his next race on the boards at Laurel, Md., and won the 10 and 25-mile races in record time, the 10 for a world speed mark of 109 mph. It was 1925 and Joe was the monarch of the board ovals, the hazardous, steeply banked and fastest speedways. He was outriding and outsmarting the greats of the game.

Later, Harley-Davidson decided to temporarily withdraw from racing. Joe went to F. Ignaz Schwinn, head of Excelsior in Chicago. Joe knew that Schwinn had quit racing after Bob Perry 1was killed, but he thought he might be able to talk the old man into reconsidering. Anyhow, Joe had heard a lot about the mechanical genius of Excelsior chief engineer Art Constantine, and wanted to meet him. During talks, Schwinn was so impressed with the talent and personality of the youngster he decided to make Joe his one-man team.

Joe continued to win on the boards and in hillclimbs, sometimes switching to a Harley for dirt track racing. Then he designed a 21.35 Excelsior to conform to size limitations of that era. However, he was unable to get the bugs out of the new machine in time for a big meet at Springfield, 111., so when he was offered an Indian for the race on the Ví-mile oval he gladly accepted. Here again he was against a star-studded field that included Eddie Brinck, home from a conquest of Australia; Art Pechar and Bill Minnick, all riding new four overhead valve, 21-in. Indians.

When the race started Eddie Brinck went wide on the first turn then cut down in front of Joe. Brinck was thrown clear, sustaining a fatal broken neck. Joe smashed into Brinck’s machine, his face striking his handlebars going up. In this single crackup his jaw, nose and collarbone were broken and a big piece torn out of his upper lip. The hunk of flesh was found on the track, sewn back and luckily left only a faint scar. Brinck died in the hospital. Joe was unconscious for two days and in the hospital eight weeks.

Joe switched to Harley after Excelsior’s motorcycle plant closed down in 1931 and he became nearly unbeatable during the 30s against such men as Lou Balinski, Jim Davis, Miny Wain and Fred Toscani.

He topped his career with a straightaway record run at Daytona Beach on the streamlined Harley. His 136 mph mark stood for 1 1 years.

In 1938, the factories agreed to withdraw support of their teams. Class A racing was suspended except on short tracks. Joe decided it was about time to call it quits. His mind was made up when, at Oakland in a 200-mile Class C race, he narrowly missed death when Dick Ince skidded in front of him and was killed when he hit the fence.

For three years Joe worked with Art Sparks building race cars at Thorne Engineering, then joined Hughes Aircraft.

Recalling his racing days, Joe rates Jim Davis as the toughest man he rode against. He picks Orrie Steele as the best of his hillclimbing rivals, with Howard Mitzel a close second.

But that’s all past him now. He’s been officiating at world record speed runs for 14 years. In fact, he has supervised more of these events than any other official in history. It’s just another Petrali record.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue