THE STORY OF IRON MAN ED KRETZ

He Sat On A Bike Like A Bull. The Longer He Raced, The Stronger He Got.

NORM HARTFORD

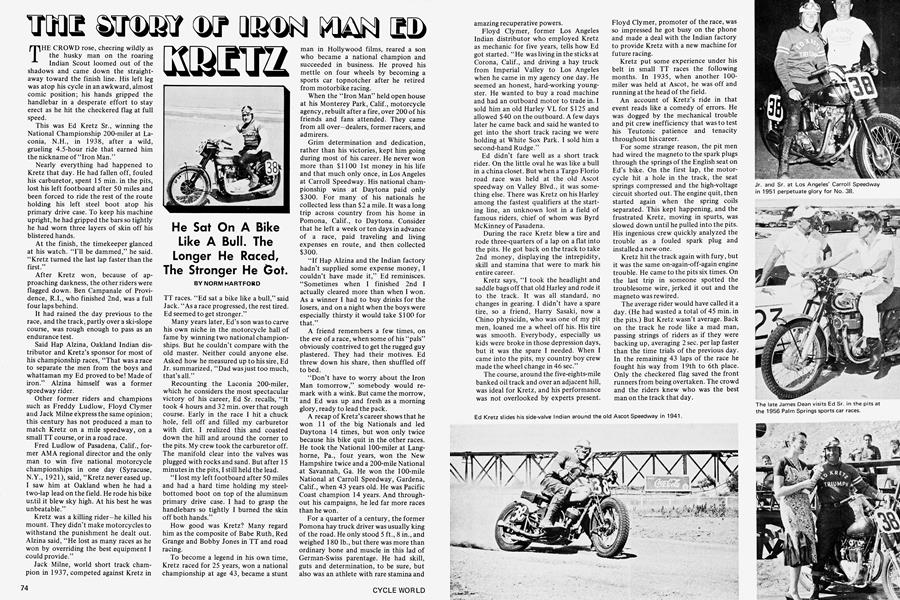

THE CROWD rose, cheering wildly as the husky man on the roaring Indian Scout loomed out of the shadows and came down the straight-away toward the finish line. His left leg was atop his cycle in an awkward, almost comic position; his hands gripped the handlebar in a desperate effort to stay erect as he hit the checkered flag at full speed.

This was Ed Kretz Sr., winning the National Championship 200-miler at La conia, N.H., in 1938, after a wild, grueling 4.5-hour ride that earned him the nickname of "Iron Man."

Nearly everything had happened to Kretz that day. He had fallen off, fouled his carburetor, spent 1 5 mm. in the pits, lost his left footboard after 50 miles and been forced to ride the rest of the route holding his left steel boot atop his primary drive case. To keep his machine upright, he had gripped the bars so tightly he had worn three layers of skin off his blistered hands.

At the finish, the timekeeper glanced at his watch. "I'll be dammed," he said. "Kretz turned the last lap faster than the first."

After Kretz won, because of ap proaching darkness, the other riders were flagged down. Ben Campanale of Provi dence, R.I., who finished 2nd, was a full four laps behind.

It had rained the day previous to the race, and the track, partly over a ski-slope course, was rough enough to pass as an endurance test.

Said Hap Alzina, Oakland Indian dis tributor and Kretz's sponsor for most of his championship races, "That was a race to separate the men from the boys and whattaman my Ed proved to be! Made of iron." Aizina himself was a former speedway rider.

Other former riders and champions such as Freddy Ludlow, Floyd Clymer and Jack Mime eipress the same opinion; this century has not produced a man to match Kretz on a mile speedway, on a small TT course, or in a road race.

Fred Ludlow of Pasadena, Calif., for mer AMA regional director and the only man to win five national motorcycle championships in one day (Syracuse, N.Y., 1921), said, "Kretz never eased up. I saw him at Oakland when he had a two-lap lead on the field. He rode his bike ur1til it blew sky high. At his best he was unbeatable."

Kretz was a killing rider-he killed his mount. They didn't make motorcycles to withstand the punishment he dealt out. Aizina said, "He lost as many races as he won by overriding the best equipment I could provide."

Jack Mime, world short track cham pion in 1937, competed against Kretz in TT races. "Ed sat a bike like a bull," said Jack. "As a race progressed, the rest tired. Ed seemed to get stronger."

Many years later, Ed's son was to carve his own niche in the motorcycle hall of fame by winning two national champion ships. But he couldn't compare with the old master. Neither could anyone else. Asked how he measured up to his sire, Ed Jr. summarized, "Dad was just too much, that's all."

Recounting the Laconia 200-miler, which he considers the most spectacular victory of his career, Ed Sr. recalls, "It took 4 hours and 32 mm. over that rough course. Early in the race I hit a chuck hole, fell off and filled my carburetor with dirt. I realized this and coasted down the hill and around the corner to the pits. My crew took the carburetor off. The manifold clear into the valves was plugged with rocks and sand. But after 15 minutes in the pits. I still held the lead.

"I lost my left footboard after 50 miles and had a hard time holding my steel bottomed boot on top of the aluminum primary drive case. I had to grasp the handlebars so tightly I burned the skin off both hands."

How good was Kretz? Many regard him as the composite of Babe Ruth, Red Grange and Bobby Jones in TT and road racing.

To become a legend in his own time, Kretz raced for 25 years, won a national championship at age 43, became a stunt man in Hollywood films, reared a son who became a national champion and succeeded in business. He proved his mettle on four wheels by becoming a sports car topnotcher after he retired from motorbike racing.

When the "Iron Man" held open house at his Monterey Park, Calif., motorcycle agency, rebuilt after a fire, over 200 of his friends and fans attended. They came from all over-dealers, former racers, and admirers.

Grim determination and dedication, rather than his victories, kept him going during most of his career. He never won more than $1100 1St money in his life and that much only once, in Los Angeles at Carroll Speedway. His national cham pionship wins at Daytona paid only $300. For many of his nationals he collected less than $2 a mile. It was a long trip across country from his home in Pomona, Calif., to Daytona. Consider that he left a week or ten days in advance of a race, paid traveling and living expenses en route, and then collected $300.

"If Hap Alzina and the Indian factory hadn't supplied some expense money, I couldn't have made it," Ed reminisces. "Sometimes when I finished 2nd I actually cleared more than when I won. As a winner I had to buy drinks for the losers, and on a night when the boys were especially thirsty it would take $100 for that."

A friend remembers a few times, on the eve of a race, when some of his "pals" obviously contrived to get the rugged guy plastered. They had their motives. Ed threw down his share, then shuffled off to bed.

"Don't have to worry about the Iron Man tomorrow," somebody would re mark with a wink. But came themorrow, and Ed was up and fresh as a morning glory, ready to lead the pack.

A recap of Kretz's career shows that he won 11 of the big Nationals and led Daytona 14 times, but won only twice because his bike quit in the other races. He took the National 100-miler at Lang home, Pa., four years, won the New Hampshire twice and a 200-mile National at Savannah, Ga. He won the 100-mile National at Carroll Speedway, Gardena, Calif., when 43 years old. He was Pacific Coast champion 14 years. And through out his campaigns, he led far more races than he won.

For a quarter of a century, the former Pomona hay truck driver was usually king of the road. He only stood 5 ft., 8 in., and weighed 180 lb., but there was more than ordinary bone and muscle in this lad of German-Swiss parentage. He had skill, guts and determination, to be sure, but also was an athlete with rare stamina and amazing recuperative powers.

Floyd Clymer, former Los Angeles Indian distributor who employed Kretz as mechanic for five years, tells how Ed got started. “He was living in the sticks at Corona, Calif., and driving a hay truck from Imperial Valley to Los Angeles when he came in my agency one day. He seemed an honest, hard-working youngster. He wanted to buy a road machine and had an outboard motor to trade in. I sold him an old Harley VL for $125 and allowed $40 on the outboard. A few days later he came back and said he wanted to get into the short track racing we were holding at White Sox Park. I sold him a second-hand Rudge.”

Ed didn’t fare well as a short track rider. On the little oval he was like a bull in a china closet. But when a Targo Florio road race was held at the old Ascot speedway on Valley Blvd., it was something else. There was Kretz on his Harley among the fastest qualifiers at the starting line, an unknown lost in a field of famous riders, chief of whom was Byrd McKinney of Pasadena.

During the race Kretz blew a tire and rode three-quarters of a lap on a flat into the pits. He got back on the track to take 2nd money, displaying the intrepidity, skill and stamina that were to mark his entire career.

Kretz says, “I took the headlight and saddle bags off that old Harley and rode it to the track. It was all standard, no changes in gearing. I didn’t have a spare tire, so a friend, Harry Sasaki, now a Chino physician, who was one of my pit men, loaned me a wheel off his. His tire was smooth. Everybody, especially us kids were broke in those depression days, but it was the spare I needed. When I came into the pits, my country boy crew made the wheel change in 46 sec.”

The course, around the five-eights-mile banked oil track and over an adjacent hill, was ideal for Kretz, and his performance was not overlooked by experts present. Floyd Clymer, promoter of the race, was so impressed he got busy on the phone and made a deal with the Indian factory to provide Kretz with a new machine for future racing.

Kretz put some experience under his belt in small TT races the following months. In 1935, when another 100miler was held at Ascot, he was off and running at the head of the field.

An account of Kretz’s ride in that event reads like a comedy of errors. He was dogged by the mechanical trouble and pit crew inefficiency that was to test his Teutonic patience and tenacity throughout his career.

For some strange reason, the pit men had wired the magneto to the spark plugs through the springs of the English seat on Ed’s bike. On the first lap, the motorcycle hit a hole in the track, the seat springs compressed and the high-voltage circuit shorted out. The engine quit, then started again when the spring coils separated. This kept happening, and the frustrated Kretz, moving in spurts, was slowed down until he pulled into the pits. His ingenious crew quickly analyzed the trouble as a fouled spark plug and installed a new one.

Kretz hit the track again with fury, but it was the same on-again-off-again engine trouble. He came to the pits six times. On the last trip in someone spotted the troublesome wire, jerked it out and the magneto was rewired.

The average rider would have called it a day. (He had wasted a total of 45 min. in the pits.) But Kretz wasn’t average. Back on the track he rode like a mad man, passing strings of riders as if they were backing up, averaging 2 sec. per lap faster than the time trials of the previous day. In the remaining 43 laps of the race he fought his way from 19th to 6th place. Only the checkered flag saved the front runners from being overtaken. The crowd and the riders knew who was the best man on the track that day.

In 1936, he entered the 200-mile national championship at Savannah, Ga. Nobody outside the Los Angeles area had heard of him, and his victory in this grind, “held over a 3-mile course of sea shells” as Ed describes the race, was a national sensation. In winning, he lowered by 10 mph the record for the event set by Rudy Rodenburg in Jacksonville, Fla., two years previously.

The next year the National was moved to Daytona Beach, Fla., and Kretz proved his previous win was no fluke by again taking the 200-miler. Later that year he won the 100-mile National at Langhorne, Pa., and everybody was ready to admit a new giant had appeared on the American motorcycle racing horizon.

When he returned to the Pacific Coast, TT racing was in full swing, but most of the events paid the proverbial peanuts. However, he entered them all, winning when his machine withstood the pace he set.

This writer was publicity man for many of Ed’s early races in Southern California during the ’30s. In pre-race newspaper articles I merely mentioned Kretz as the favorite and played up the abilities and chances of the other riders. I knew unless something extraordinary happened Ed was a lead pipe cinch. Fans attended to see Kretz outstripped or because they were curious as to who would finish 2nd.

His chief rival in Southern California TT races was a lad of dual identity, Bruce (Booboo) Pearson, alias Buck Bryden. Because he worked for the Bank of California, which frowned on his racing, Bruce saw fit to change his name on the entry blank to Bryden. Pearson, Byrd McKinney and Harrison Reno, later

Kretz’s business partner, gave the husky fellow some competition, but toward the end of a race they would usually tire and the “Iron Man” would win, a half lap or more in front.

At this time Kretz became a motionpicture stunt rider. He appeared as a motorcycle cop in a George Raft film, “She Couldn’t Take It,” and with Ginger Rogers and other stars. When there was no race on a Sunday, he often performed at county fairs. His trick riding exhibitions included mounting a machine backward and doing deliberate gravel spins. He also could enact a stunt known as “laying down at speed,” performed with excellence by few pro racers.

His practice and performance of the latter stunt was to come in handy in the 1940 200-mile national championship on the paved Oakland Speedway. He found himself without brakes, traveling 105 mph, when he flew into a turn and saw a man down in front of him. He had the choice of trying to dodge or laying down, when an oil slick caused by the fallen machine threw him into a slide. He was thrown from his seat, dragged up the bank of the turn and slammed against a retaining wall. He lived, but emerged with an injured shoulder. And he was back racing again a month later.

During his career, Kretz often fell off. It was understandable. An explanation came from “Wild Bill” Cummings, the Indianapolis auto race winner, who once raced a motorcycle against Kretz. Said Cummings, “To that guy there are no turns, all straightaways. He never shuts off.”

Battered and battle-scarred during his campaigns, Ed remained indestructible after 25 years of warfare on 100 different tracks. His injuries included two concussions, two severe shoulder injuries, several cracked ribs, and bruises and bums too numerous to count. His life often was saved by his amazing coolness, strongly developed reflexes, quick thinking in face of danger and his toughness.

In one of Ed’s last races before World War II all of his natural and acquired instincts and abilities to cheat death saw him through one of the worst accidents in motorcycle history. It was during the national championship 200-miler on the mile paved Oakland oval in 1941.

Kretz was at his best. By the 38th mile he had lapped the field. Going into a turn, Tommy Hayes of Texas, fighting for 2nd position, saw Kretz coming and gave his cycle the gun. At top speed Hayes wheeled out around Ben Campanale and shot into the steeply banked turn. Hayes had entered the curve too fast, and at 100 mph hit a rough spot and went flying from his machine. He died instantly.

Campanale, traveling right behind, went down. Kretz came along, saw a momentary hole between the riders and their flying bikes and went through, just in time. A moment later, Hayes’ bike came down on the track, closing the gap.

There were three men following Kretz— June McCall, Jimmy Kelly and Sam Arena. McCall met instant death. Kelly was knocked unconscious. Sam Arena (whom critics claim was one of the few men in history outstanding in any type of motorcycle racing) pulled “a Kretz” and laid his machine down at 100 mph without serious injury. The toll for the pile-up was two dead, with Kelly and Campanale in the hospital for nearly a year. Arena was shaken up, but got back in the race.

Kretz kept the lead, and was seven miles in front of the field at the end of the 167th lap when the unusual happened. The front chain broke. He was forced out on the 168th lap, just 32 miles from the finish.

The war years took him out of competition but when peace came, at 44, he won his first major postwar race at Laconia, the National TT Championship 100-miler. Recalls Ed: “This year, my rear chain broke and I coasted down the same hill to the pits as I did in ’38. My pit men cut a length of chain and I installed it. I lost the lead for ten laps, then I regained 1st place and held it to the finish.”

In 1946, he became a grand slam champion with victories in Nationals at Daytona, Laconia and Langhorne.

About this time Ed started coaching his son, Eddie Jr., in earnest. The taller, but husky youngster resembled his sire on the track and was determined to carve his own niche.

In 1950, at Laconia, they raced as a father-son team. Eddie Jr. did his part, winning the 50-mile Amateur race on Saturday. On Sunday, Pop Kretz, out to hold up his end, started in 12th position and had forged to the front at six miles. Then the old Ascot hoodoo caught up with him, and he came to the pits with ignition circuit trouble. This was repeated four times until the pit crew discovered it was a faulty condensor. Kretz then was eight laps behind.

For the next 26 miles he rode like a wild man and was making record time passing the youngsters when, at 90 mph, his front brake locked. He was thrown from his bike and sent rolling down the pavement. He turned over five times before he got to his feet and walked, unaided, to the pits. His helmet had been smashed, his sweater burned from his back and skin torn from his face and hands. But he stood and watched the race to the finish before allowing the ambulance to drive him to an emergency hospital.

Kretz calls his victory in the championship 100-miler at Carroll Speedway, Gardena, in 1954, his surprise thriller. “I had not planned to enter but at the last minute Fred Ford talked me into the race. So I took along my road 650 Triumph with a small mustang tank. I should have had a larger tank. But they were paying lap money, so I said to Fred, ‘Let’s go down and get what lap money we can.’ I won the trophy dash and then got out in front in the 100 and held the lead, lapping Joe Leonard, who finished 2nd. All the Harley and Triumph pit men expected me to blow my engine, but when I kept going they had gas cans ready for me. But I didn’t have to make a pit stop. I finished with about a quart of fuel. I turned the last laps a half second faster than the first.

“In all I won the Pacific Coast championship 14 years. Eddie, my boy, won it two years. Then, when he went into the service in 1953, I took it the two years he was gone. I won a couple of 50-mile races at the old Oakland one-mile banked track. I still hold the record on my 1948 Indian. I turned the mile in 38 sec.”

Today Kretz, at 57, retains that mastery of a bike. He often goes to the desert on a week-end and cavorts with the youngsters. Recently, near the old mining town of Calico, Calif., a dozen riders spent several hours on a Sunday, trying to ride up a sharp incline and over a hill. Nobody made it. Kretz arrived, glanced at the hill and somebody made the mistake of betting the “old man” $ 10. Kretz went over the first try.

The “Iron Man” says two of the best youngsters today are Skip Van Leeuwen of Los Angeles, in TT competition, and Gary Nixon of Baltimore, in road racing. He says the only old-timer he has heard of who would have given him a run for his money in road racing was Don Johns. If he raced today, he would choose a Triumph the make he has ridden in his last three victories. A big thrill of his career? Lapping his idol, Cordy Milne, in the Ascot Targo Florio.

He names as the best men he has raced against California riders Bruce Pearson of Los Angeles, Byrd McKinney of Pasadena, Jack Cotrell of San Francisco, Ray Eddy of San Francisco, and Sam Arena of San Jose; Ben Campanale of Providence, R.I.; and Tommy Hayes of Fort Worth, Tex. Then he admitted that if he raced tomorrow, and everything else were equal, the man he would regard as his toughest threat would be the versatile Sam Marina, now the owner of a motorbike shop in San Jose, Calif.

Born irt San Diego, Calif., in 1911, Ed was the youngest in a family of 11 children. When he started racing, his father, a Seventh Day Adventist deacon, and some of his deeply religious brothers and sisters considered him headed for hell on a motorbike. “I was the only rider in the family,” he recalls. “They didn’t like it at first, but later came to see me race.”

Usually even tempered, the husky Kretz is a punch-throwing Marciano when ired. During World War II, Ed served as motorcycle instructor at an army base in Pomona. On one occasion, off the base, four GIs confronted him in an argument. After failing to talk his way out of a fight, Ed knocked one man unconscious against the wall of a building and hit another, who toppled completely over the hood of a car. The other pair beat a hasty retreat.

How good was Kretz?

Joe Walker of Santa Ana, Calif., former mechanic for Lloyd “Sprouts” Elder, international speedway ace, says, “It’s hard to compare Kretz to the old cross-country riders like Cannonball Baker, Roy Artley and Wells Bennett, who came before him. They rode under different conditions. Kretz came along about the time TT racing became popular, and he dominated this competition. At his peak, nobody could match him on a mile track. In the National road races, if Ed had had a bike capable of withstanding the beating he gave it, there would have been no need to hold the race. They could have simply wired Ed the prize money.”

Kretz proved he could have been great in auto racing when he broke sports car records right and left at the wheel of a small Triumph. He once took 3rd overall behind a Ferrari and Cadillac in a six-hour grind at Torrey Pines, Calif.

Today he lives comfortably in Monterey Park with his second wife, the former Mary Titus of the Oklahoma oil family, and two children. His first wife, Irene, to whom he was married 34 years, passed away in 1962. They had two children, Ed Jr. and a daughter, Donna. Ed Jr. is manager of a prosperous Monterey Park agency, which carries Triumph, Honda, Suzuki, BMW and Maico.

Recalling the days when newspapers ran his picture on full-page cigarette ads, we offered him a smoke. “No thanks, never use them,” he smiled.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsRound Up

September 1969 By Joe Parkhurst -

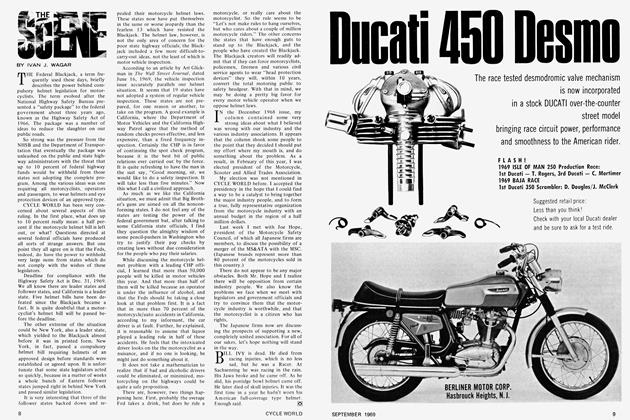

Departments

DepartmentsThe Scene

September 1969 By Ivan J. Wagar -

Departments

DepartmentsThe Service Department

September 1969 By John Dunn -

Letters

LettersLetters

September 1969 -

Competition

CompetitionThe Firecracker

September 1969 By Ivan J. Wagar -

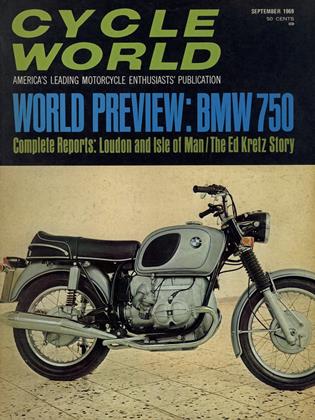

Preview

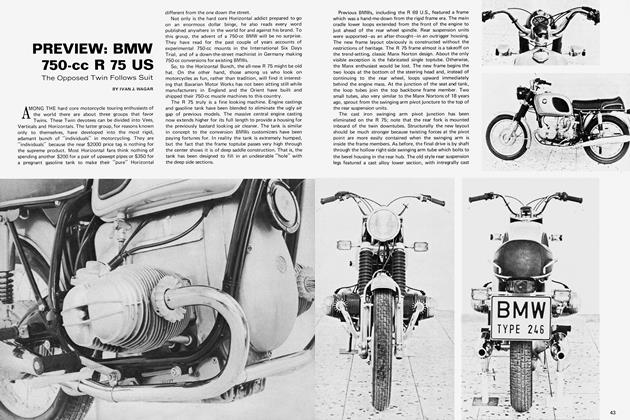

PreviewBmw 750-Cc R 75 Us

September 1969 By Ivan J. Wagar