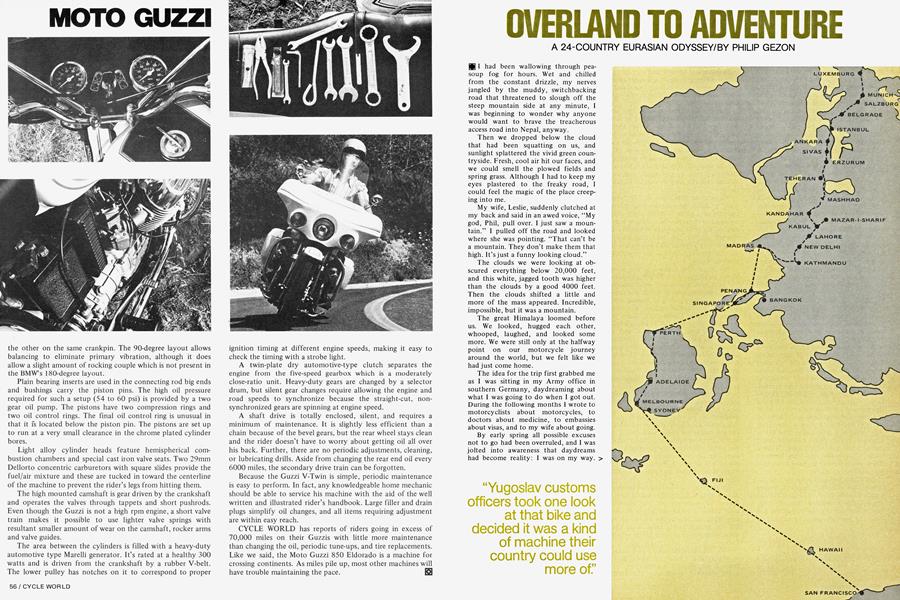

OVERLAND TO ADVENTURE

A 24-COUNTRY EURASIAN ODYSSEY

PHILIP GEZON

I had been wallowing through peasoup fog for hours. Wet and chilled from the constant drizzle, my nerves jangled by the muddy, switchbacking road that threatened to slough off the steep mountain side at any minute, I was beginning to wonder why anyone would want to brave the treacherous access road into Nepal, anyway.

Then we dropped below the cloud that had been squatting on us, and sunlight splattered the vivid green countryside. Fresh, cool air hit our faces, and we could smell the plowed fields and spring grass. Although I had to keep my eyes plastered to the freaky road, I could feel the magic of the place creeping into me.

My wife, Leslie, suddenly clutched at my back and said in an awed voice, “My god, Phil, pull over. I just saw a mountain.” I pulled off the road and looked where she was pointing. “That can’t be a mountain. They don’t make them that high. It’s just a funny looking cloud.”

The clouds we were looking at obscured everything below 20,000 feet, and this white, jagged tooth was higher than the clouds by a good 4000 feet. Then the clouds shifted a little and more of the mass appeared. Incredible, impossible, but it was a mountain.

The great Himalaya loomed before us. We looked, hugged each other, whooped, laughed, and looked some more. We were still only at the halfway point on our motorcycle journey around the world, but we felt like we had just come home.

The idea for the trip first grabbed me as I was sitting in my Army office in southern Germany, daydreaming about what I was going to do when I got out. During the following months I wrote to motorcyclists about motorcycles, to doctors about medicine, to embassies about visas, and to my wife about going.

By early spring all possible excuses not to go had been overruled, and I was jolted into awareness that daydreams had become reality: I was on my way.

"Yugos~av customs officers took one look at that bike and decided it was a kind of machine their country could use more of'

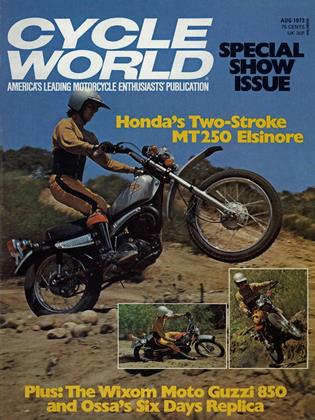

I made the trip on a new R50/5 BMW, purchased right from the factory in Munich with my Army hoardings. The 500cc BMW has a reputation for toughness, and it can swallow regular—a must, since any bike making the trip faces interludes with pig sludge for fuel.

I crammed the bike with spare parts, a 1-gallon container of emergency gas, and with unusual foresight taped my spare brake and clutch cables ISDTstyle, parallel to the working cables. But as I rode to Luxemburg in early March to meet Leslie at the Icelandic Air Terminal, I still couldn’t imagine how I was going to load two 60-lb. frame packs stuffed with mountain-climbing hardware, two ice-axes, 170 lb. of me, 135 lb. of Leslie, and the spare gasoline all onto my cringing motorcycle.

Eventually we lashed the packs sideways to the bike frame with the entire weight resting on the exhaust pipes, bungied the gas container onto the horizontal platform of the factory rack and, with snowflakes fluttering down, waddled our way to Munich.

We got as far as Salzburg, Austria, before fishtailing in the snow got completely out of hand. Then we decided to ship us and the bike by rail to Belgrade, Yugoslavia.

Big mistake. Yugoslav customs officers took one look at that bike and decided it was the kind of machine their country could use more of. So they impounded it “on suspicion that it might be an import item.” Since the slush was a foot and a half deep, Leslie and I had no choice but to avail ourselves of the government-controlled hotel facilities (no other kind exists) at a cost of $8 per night.

I had begun to feel pretty depressed by the time, three days of negotiation with (I counted them) 24 different offices, and several small fees and bribes later, I finally procured the 24 official stamps required to get the bike paroled.

We bought train tickets to Thessaloniki, Greece, for us and the bike and thought our troubles were over. Unfortunately, the Yugoslavs use a different alphabet and their writing is indecipherable; when our train pulled into balmy Thessaloniki we discovered that what the official had sworn said “Thessaloniki” had really said “the border.” They weren’t going to turn loose that bike without a struggle.

So I took the next train back to the border, and after three hours of hassling I got the BMW freed. As I sped back to Thessaloniki I decided that the only plus about our stop in Yugoslavia had been the treat of watching unmatched bureaucracy at work.

“Thessaloniki is where old BMWs go to die!’

Thessaloniki is where old BMWs go to die. The Greeks chop them up and make three-wheeled delivery carts out of them. Spare parts and experienced mechanics abound.

We snooped around the city for a couple of days, exploring the ruins of a tremendous old fortress and gorging on delicious Greek pastry, and then continued our journey along the Greek coast and over the Turkish hills to Istanbul.

Crossing the Bosporus on the ferry in Istanbul was a thrill. We looked across the choppy water toward the low, bare hills on the other side and tingled with excitement. Asia! We half expected to feel transformed when we stepped off the ferry and onto the ancient ground, but the same freeway that had taken us into town took us out again, and we realized that the Asia we sought still lay ahead.

We got our first taste of the “real Asia” at dawn the next morning. After camping in a green field for the night, we woke to the eerie wails of Islam holy men calling their followers to worship. I crawled out of the tent and nearly tripped over a farmer who was prostrate on the ground, making his morning bows to Mecca.

We spent the following two days winding along good roads through country that was sometimes mountainous and sometimes plainsland, but was consistantly underpopulated, barren and desolate, particularly under its cold blanket of early March snow. Then, in the late afternoon, the road widened into a six-lane super-highway and I fohnd myself fighting for survival among a mass of speeding, weaving, bumper-to-bumper Yank-tanks. The trip into downtown Ankara was short, but terrifying. Even Leslie quit blabbing about the scenery and just hung on grimly.

While in Ankara I found a small machine shop and had a pair of bike racks built from IxVz-in. square tubing, designed to jut out from the factory racks and to relieve the overstrained exhaust pipes of their load. While I waited the hospitable shop owner plied me with tea and carefully supervised the work, which was carried out by young boys 10-16 years old. Total cost for six hours of hand work and perfect welds? Less than $5.

On our way out the bike had trouble getting up a slick, muddy embankment. Before we could get off, our friendly shop keeper reached out and with one arm lifted the rear of the loaded BMW off the ground and pushed it up the slope. Remind me never to tangle with a Turk.

The racks gave the bike a low center of gravity and a balanced, stable load. Once I got used to maneuvering the extra weight I could gun the BMW through corners with almost the same ease as when we were only two-up. Unexpected benefits were increased safety in prangs and, later on, extra breathing room in humanity-packed Indian streets.

The bike got its last shot of super for the next 500 miles as we left Ankara. I fed it super whenever possible: beyond the Bosporus regular is a synonym for trash. Shortly before, gassing it up with regular had caused fuel starvation problems, which I corrected by cleaning the petcock screens and float bowls.

Since it looked shorter than the other possible routes, I decided to take the central road through Sivas to Erzurum. Two spring storms bracketed us fore and aft as we sped into Sivas. Along the way we had encountered several areas where the rain had washed 2-4 in. of red clay mud across the road in 5-40 yard stretches. Just beyond Sivas we cleared a hill at 35 mph, only to discover a 6-in. deep mud slide stretched out in front of us.

I straight-legged it upright for a few yards, but after the third fishtail we slithered sideways into the mud. The engine, still running, drove the machine into a backward flip and it nose-dived onto its handlebars.

Leslie, having catapulted over my head, was long gone down the slide. The bike and I came to a stop just in time to see the front of a truck appear at the top of the hill. The driver slammed on his brakes and skidded to a stop just yards from where I was wallowing helplessly in the mud.

Although my old-type crash bars prevented cylinder damage, the valve covers projected enough beyond them for the asphalt to abrade a hole in the right-hand one. Luckily, I had a spare valve cover, so I picked out the globs of mud from the valves and repaired the damage.

The bike kicked over with a single stroke of the starter and, disgruntled and plastered with mud, we limped back to Sivas for a two-day wash-and-rest binge.

Our R&R gave the rains time to pass, and we started off for Erzurum on reasonably dry road. Unfortunately, the road became steadily narrower and steeper until the bike’s first gear was barely adequate to cope with the upgrades and my hands were barely able to hold the brakes on the down-grades. Snow covered the towering mountins all around us, although it was absent from the road.

This stretch was one of the most difficult on the journey, and I could have avoided it by taking the turn-off to Samsun, 80 miles past Ankara, following the Black Sea coast to Trabzon, and then turning inland to Erzurum.

Beyond Erzurum we traversed 9000ft. passes until the mountains finally melted into hilly lowlands and then into plains. The huge, snowy pyramid of Mt. Ararat dominated the scene, and the wide, fenceless plains below it were dotted with small herds of grazing goats and sheep. We passed a group of five camels, the first we had seen, plodding along the road, loaded with so much hay that they looked more like animated haystacks than camels. We could easily imagine that life hadn’t changed much since the days of the Old Testament.

On the eastern Turkish plains we ran into the only incidents of overt hostility encountered on the entire trip. The Turks in this congenial area spit at us, threw stones, brandished sticks, and set their huge dogs at us. After a few miles of that I began turning up the wick rather than braking, shooting through the small towns at 50-60 mph.

When we crossed the border into Iran a few hours later, a pleasant, welleducated young Iranian told us that the hostility had not been as much antiAmerican as anti-everyone who isn’t an eastern Turk. A stone thrower had shattered his windshield on a trip to Ankara the year before, and he said nearly everyone suffered similar abuses. A German motorcyclist camping in the area a few years before had been found with his throat cut.

This cheerful news, added to our own experiences, made us enter Iran with a spirit of thanksgiving, particularly when the Turkish potholes abruptly turned into a spacious, wellengineered highway. The Iranians we met along the way were warm and helpful, eager to show us the best restaurants and hotels, to share a meal with us, and to practice their schoollearned English on sympathetic ears. And the gasoline was good and easy to come by at the government-controlled stations, which even had premium gas and...clean toilets!

After hearing all the horror stories about Teheran traffic, supposedly the world’s worst, we decided to bypass Teheran completely. Instead, we headed down the winding, Sunday-driverinfested road to the Caspian Sea, and then along the coast to the east end, where we again dipped into the desert.

Twenty miles from nowhere we dropped one of the carburetor float bowls. I plugged the leakage with a plastic bag and we limped into the small desert town of Gonbad, where a machine shop made up a new bowl out of brass for about $3.

After spending the night in the spare room of a gas station, we encountered the only part of the east-west road system that the Iranians have not yet completed. For 200 miles east of Gonbad the road surface is composed of dirt and large-diameter pebbles, and the motorcycle bumped and jounced painfully along at 20-25 mph.

“We woke to the eerie wails of Islam holy men calling their followers to worship!’

The dry, rolling desert grew progressively more desolate, and everything took on the color of rain-starved dust. Forty miles outside of Mashhad, the second-most-holy city of Islam, twin rows of hand-planted, hand-watered trees appeared and shaded the road all the way into town. Coming out of the parched desert the cool green looked as wonderful to us as it must have looked to the thousands of pilgrims who flock to Mashhad each year, by car, by camel or horse, and by foot.

From Mashhad on through Afghanistan the desert is frightful. With my customary foresight, I failed to fill our canteens at the frontier and we spent a parched night camped in a wadi with the sand sifting through infinitesimal seams in the tent. The second night we camped behind some rocks, hoping they would give us adequate protection from the eyes of passing drivers and wandering nomads. I was too hot inside my sleeping bag and too cold out of it. Two-inch-long beetles clicked at us balefully as they rolled large balls of dung across the sand near our camp, making sleep even less likely.

Roaring into a rare roadside settlement the next morning, I was so frantic for a drink of water that I neglected to wait the 20 minutes for my chlorine tablets to do their work. The following day I came down with dysentary.

Duststorms and twisters limited visibility on the stretch into Kandahar to about 200 yards, and a searing wind drove sand particles into any patches of skin we couldn’t cover. The engine got so hot that I pulled over and stopped to let it cool. That gave me a chance to look around. I’d never seen anything so barren. We couldn’t even find a weed.

I started getting haunted thoughts like, “What if the engine seals melt, or the bike won’t start again? Without water we could die out here in a few hours.”

But the bike did start, and carried us into the green oasis of Kandahar, where we found a hotel with a cold shower and called it quits for the day.

In the morning I gassed up the bike and we set off again on the excellent Afghan roads. The bike still ran well but was beginning to cough and sputter. The Russian-made gas is reasonably refined, but only has an octane rating of 50.

Given a choice, I took the wrong road out of Kandahar and ended up unknowingly at the Pakistan border. For half an hour I struggled to explain to the non-English-speaking guards that I wanted to go to Kabul, while the guards, waving their arms and pointing wildly at the map, tried to explain that I was going to Pakistan.

This was not the first time, nor the last, that I came to grief at border crossings. Dealing with officialdom is not my strong suit in any case, but the Asians turn the bureaucratic runaround into a holy rite. Crossings seldom took less than two hours, which I spent being shuttled from office to office, waiting in corridors, producing the same documents five or six different times, and convincing some particularly conscientious official that he didn’t really want me to unload the bike and empty out our packs.

By the time they finished with me I usually felt like a blithering idiot. At one crossing I thankfully jumped on the bike and gunned it into gear for my getaway. Only one problem: in my hurry I had neglected to put up the kickstand. It caught on a curb and we sprawled across the front lawn of the office. To make matters worse, I was so effectively pinned that the border guards had to come out and get me loose.

That lower route into Pakistan, incidentally, is bad news. I met a party of Aussies in New Delhi who had had a run-in with Pathan bandits while making the desert crossing to Quetta. The bandits had swarmed down on them from the nearby hills and the Australians were barely able to outdistance them. A neat row of five bullet holes in the front of their bus suggested that the bandits had not been merely fooling around.

On our last night in the desert we camped with the lights of nomad campfires all around us. With the dysentary and rocky ground I spent a miserable night, waking shortly before dawn. The nomads were already stirring, and since we wanted to be on the move before a herd of goats trampled us, I wakened Leslie and we started breaking camp.

We were sitting on our rolled up sleeping bags munching bread and sardines when over the rise loomed a hairy, wild-eyed nomad about 7-ft tall. He noticed us, jumped, and eyed us suspiciously from under heavy dark brows. Not being too well versed in nomad etiquette, I smiled in what I hoped was an ingratiating way, and said, “Hello. Would you like to share our bread and sardines?”

He jumped again, yelled something, and started toward us. “Oh my god, he’s got a gun,” Leslie moaned.

He did, too. And it, also, was about 7-ft. tall.

“The uncrowded jungle road was paradise compared to the packed, bewildering byways of India!’

But after looking us over carefully, he crouched down, ate a few pieces of bread and drank some water. Then with an abrupt, but polite, gesture, he unfolded himself and continued on his way.

That afternoon, in the midst of the first rain since Turkey, we entered Kabul, home of Afghan coats, hippies, and the best financial Black Market in the world. We stayed there a few days while I recovered from my ailments. The endless rows of tiny shops and lively bazaars were fascinating, and for the first time since we had entered Asia Leslie felt completely safe and confident walking through the streets by herself.

On a side trip to Mazar-i-Sharif in northern Afghanistan the BMW choked and gasped up an icy pass and plunged through the Russian-built Salang Tunnel which, at 10,000 feet, is the highest vehicular tunnel in the world. The bike lost so much power that Leslie had to get off and push before I could get over the summit.

After returning to Kabul we continued down the winding, spectacular road leading to the Pakistan border and across the famous 33-mile Kyber pass. Pakistani authorities close the road at night because of bandits, and we got there just in time to cross that evening. At the top of the pass we had a good laugh over a sign with arrows pointing to two parallel roads, one picturing a camel and the other, a car.

Upon arriving in Lahore after a long day’s drive from the border I did the usual wrong turn bit and landed in the old section of town. Milling crowds, semi-controlled ox-carts, and raucoushorned autos pushed and shoved aimlessly around us. At one point I found myself exchanging stares with two huge Brahma bulls. We were grateful for the projecting bike racks which protected us a little from the vast press of humanity around us. By the time we had inched our way onto a passable road again I was beginning to worry that the clutch would burn up with the constant slippage.

Ferozepor is the only permissible crossing point into India. Our one-day, 370-mile dash from there to New Delhi demanded my utmost concentration to maintain speed while avoiding the human and animal obstructions. We quickly learned to plan our schedule so that we would pass through as many of the large towns as possible in the very early morning. They are, without exception, clogged and baffling, and virtually impassible during daylight hours.

I got the bike serviced for $4.50, including all lubricants, at a small New Delhi garage. The mechanic even threw in a free and badly needed wax job.

New Delhi is a modern, beautifully planned city that seems more British

than Indian. While we waited for visas I did some sightseeing and bargained for a few gifts. Leslie had dysentary and could do little but lie in bed in the muggy, 100-degree heat, and suffer.

I had expected to be in Nepal two or three days after leaving New Delhi, but a combination of gastro-intestinal problems and sunstroke prevented us from doing more than 100-150 miles a day. One-track roads with sharp, 4-in. dropoffs on each side compounded my problems. Barrelling trucks often forced me onto the shoulder, and I learned later that the drivers get a bonus for reaching their destinations ahead of time. They don’t let anything come between them and their bonuses.

Not only the homicidal truck drivers, but also the people, slow-witted and unaccustomed to vehicles, made driving conditions treacherous. On the way to the Ganges River crossing I was speeding along relatively uncrowded roads at about 45 mph. Seeing a young bicylist pedaling along the road in front of me, I honked and pulled out to pass him.

Suddenly the kid swerved back toward us and collided with the cycle. We crashed onto the road and skidded on the dirt and asphalt. Leslie, who had flown off over my head, was tumbling along ahead of me. The bike caught my leg and dragged me along with it.

When we finally stopped sliding a group of villagers ran out, lifted the bike off me, and helped me up. One man, who seemed to be the leading citizen and spoke good English, kept saying, “You are not to worry. It was not your fault. They can’t touch you. You are not to worry....” No one took much notice of the kid, who was apparently unhurt and slunk off in disgrace.

My leg hurt and I had various cuts and scrapes, and Leslie, who had not been feeling well anyway, was badly shaken and angry. She had refused to wear boots because of the heat and had a gash on one sandaled foot. The cut, left unattended, later became badly infected, another warning that any open wound, however trivial, needs attention in India’s hot, infectious climate.

Later on the same afternoon we were cruising along a shady road, saw three men, walking ahead of us, honked, and started to pass. Sure as shootin’, one of them swerved right back into the cycle. This time, however, he merely bounced off a pack and landed on his back in the road. We kept right on going.

I had my choice of two possible routes across the Ganges: an 8 a.m. ferry from Patna and a bridge at Mokema that involves a detour of 125 adventure-filled miles. Thinking back on the nightmare stretch we had just covered, we took the ferry.

That ride, at least, was pleasant, on an archaic 19th century British steamer with cheap fare—less than 50 cents for me, Leslie, and the BMW.

. At last we crossed the border into Nepal. The uncrowded jungle road was paradise compared to the packed, bewildering byways of India. We neglected to buy food at the border crossing and were unable to get anything but a bunch of bananas for dinner.

Consequently, our hungry stomachs awakened us before dawn and we were on the road by 6 a.m. Our early start was a stroke of luck—we had an hour of riding before the rains hit.

The Tribhuvan Rajpath from the Indian border to Kathmandu rapidly degenerated into switchbacks, mudslides, and water-filled gullies caused by absence of culverts to sidetrack the rainwash. As we started down the far side of the pass we passed trucks by the dozens stalled beside the road. At the front of the line we discovered a work crew hacking at a massive landslide that blocked the road. When they at last managed to clear a narrow passage, our two-wheeled vehicle was first through, accompanied by cheers, claps, and waving shovels.

The Indians built the Rajpath for Nepal with the intention of making it easy to block and defend in case of Chinese invasion. Its maze of tortuous curves and sidewindings takes 100 miles to cover the 40-mile straight-line distance between Kathmandu and the border. A cyclist can expect to spend at least eight hours on the road.

By the time we arrived in Kathmandu in early May the skies were already beginning to cloud over, threatening an early monsoon season. But we managed to enjoy two facinating months of hiking and climbing before our umbrellas ceased to fulfill their function and simply acted as sieves. Furthermore, by that time in addition to our dysentary we had hepatitis, worms, sore feet, and acute exhaustion. We decided it was time to move on.

While we were trekking we had stored the BMW in a shed in the Peace Corps compound. I got it out and polished it up for the trip. But landslides on the Rajpath—seven in one night—delayed us a week before we could start for our next destination, Madras, India, 1660 miles south of Kathmandu.

The 12-day trip was fraught with typical Indian traumas and discomforts, but by creeping along the roads like a paranoid snail I arrived without slaughtering any of the unwary animals and humans who often loomed out at us disconcertingly from behind opaque sheets of rain. I attributed our unscathed arrival to the will of Shiva, supreme god of Hindi and obviously the man in control in those parts.

Overland travel through Burma is not permitted; so the land traveler headed for Australia or Malaysia must find other means of transportation. From Madras I secured passage across the Bay of Bengal to Malaysia on the steamer “Rejula,” at a cost of $90 per person and $40 for the bike.

A week of pleasant, but rainy, sailing rested us from India’s clamor and brought us to Penang, one of Malaysia’s chief port cities. Because our rear tire was getting bald, we had previously ordered a new one from Australia. With customary malicious timing, it was absent upon our arrival in Penang.

So we took the train to Bangkok and spent a week looking at temples and floating markets, windowshopping, and stuffing ourselves with fresh pineapple. Bangkok was a culinary delight. Prices were higher than in the rest of Asia, but the food was delicious, and safe. Digestive disorders left us for the first time since we had entered Asia.

The noisiest buses in the world live in Bangkok. They roar through town on 6-lane super-highways, their engines turning out about 130 decibels. India was a quiet, secluded backwater compared to the thunder of industrialized Bangkok. We both enjoyed renewed contact with Westernized society, but exposure soon became overexposure, and our enjoyment was brief.

When we returned to Penang our tire was waiting for us, and we spent the following two days on excellent roads that wound along the eastern side of Malaysia to Singapore.

In Singapore we not only had problems securing passage to Australia, but also experienced difficulties with the Australian High Commission, who would not let us into their country without ingoing and outgoing tickets and at least $500 cash each. We had to wire home for money.

While waiting we camped on the beach. As we slept one night someone ripped off my camera and lenses, our coats, and $60 cash.

Once on the steamer “Centaur,” however, our troubles were over. We disembarked in Perth and passed through customs without hassles, since motorcycles are allowed in customs-free for one year. In Perth the BMW got its first really professional tune-up since New Delhi.

After a week in Perth we started east across the famous Nullarbor Desert route to Adelaide and then to the east coast, a total of 2000 miles in six days. The entire route is paved except for 300 miles in South Australia. Due to the heat we drove mostly at night. That, however, left us to the mercy of the kangaroos, who came bounding across the road in herds of 10s and 20s. Furry carcasses along the roadside attested to the fact that other drivers were not as lucky as we were in avoiding them.

Gasoline stops are rare on the crossing, and traffic is sporadic, so it pays to watch the gas level and water supplies.

After juggling our finances (low) and our reserves (nil) in Melbourne, we reluctantly decided to sell the BMW in order to get ourselves back home, since previous time commitments in the U.S. prevented us from staying there and working for awhile.

We were both disconsolate over the loss of our trusty bike and our failure to complete the trip. But after thinking back on what we had accomplished, we didn’t feel so bad. It was quite a journey.