MICHIGAN'S PARE MARQUETTE TRAIL

DAVE SANDERSON

AN 800-MILE RIDE PUT TOGETHER BY AND FOR BIKERS

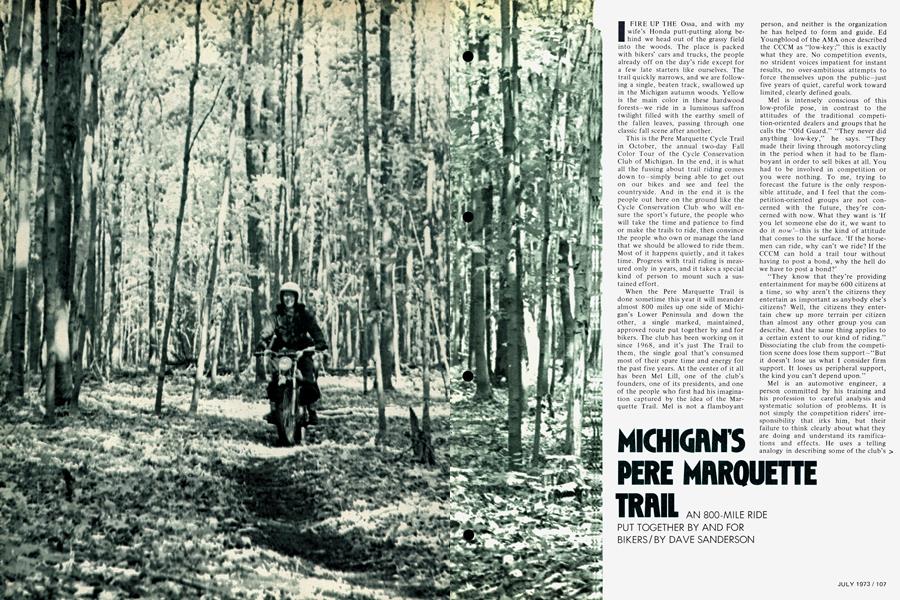

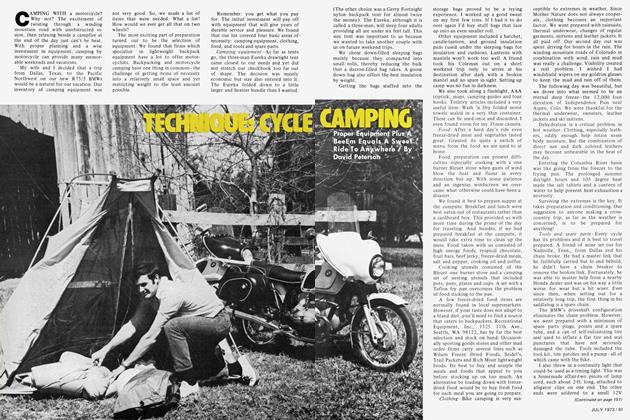

I FIRE UP THE Ossa, and with my wife's Honda putt-putting along behind we head out of the grassy field into the woods. The place is packed with bikers' cars and trucks, the people already off on the day's ride except for a few late starters like ourselves. The trail quickly narrows, and we are following a single, beaten track, swallowed up in the Michigan autumn woods. Yellow is the main color in these hardwood forests—we ride in a luminous saffron twilight filled with the earthy smell of the fallen leaves, passing through one classic fall scene after another.

This is the Pere Marquette Cycle Trail in October, the annual two-day Fall Color Tour of the Cycle Conservation Club of Michigan. In the end, it is what all the fussing about trail riding comes down to-simply being able to get out on our bikes and see and feel the countryside. And in the end it is the people out here on the ground like the Cycle Conservation Club who will en sure the sport's future, the people who will take the time and patience to find or make the trails to ride, then convince the people who own or manage the land that we should be allowed to ride them. Most of it happens quietly, and it takes time. Progress with trail riding is meas ured only in years, and it takes a special kind of person to mount such a sus tained effort.

When the Pere Marquette Trail is done sometime this year it will meander almost 800 miles up one side of Michi gan's Lower Peninsula and down the other, a single marked, maintained, approved route put together by and for bikers. The club has been working on it since 1968, and it's just The Trail to them, the single goal that's consumed most of their spare time and energy for the past five years. At the center of it all has been Mel Lill, one of the club's founders, one of its presidents, and one of the people who first had his imagina tion captured by the idea of the Mar quette Trail. Mel is not a flamboyant person, and neither is the organization he has helped to form and guide. Ed Youngblood of the AMA once described the CCCM as "low-key;" this is exactly what they are. No competition events, no strident voices impatient for instant results, no over-ambitious attempts to force themselves upon the public-just five years of quiet, careful work toward limited, clearly defined goals.

Mel is intensely conscious of this low-profile pose, in contrast to the attitudes of the traditional competi tion-oriented dealers and groups that he calls the "Old Guard." "They never did anything low-key," he says. "They made their living through motorcycling in the period when it had to be flam boyant in order to sell bikes at all. You had to be involved in competition or you were nothing. To me, trying to forecast the future is the only respon sible attitude, and I feel that the com petition-oriented groups are not con cerned with the future, they're con cerned with now. What they want is `If you let someone else do it, we want to do it now'-this is the kind of attitude that comes to the surface. `If the horse men can ride, why can't we ride? If the CCCM can hold a trail tour without having to post a bond, why the hell do we have to post a bond?'

"They know that they're providing entertainment for maybe 600 citizens at a time, so why aren't the citizens they entertain as important as anybody else's citizens? Well, the citizens they enter tain chew up more terrain per citizen than almost any other group you can describe. And the same thing applies to a certain extent to our kind of riding." Dissociating the club from the competi tion scene does lose them support-"But it doesn't lose us what I consider firm support. It loses us peripheral support, the kind you can't depend upon."

Mel is an automotive engineer, a person committed by his training and his profession to careful analysis and systematic solution of problems. It is not simply the competition riders' irre sponsibility that irks him, but their failure to think clearly about what they are doing and understand its ramifica tions and effects. He uses a telling analogy in describing some of the club's critics: “You know, we have gotten credit in some people’s eyes for such things as the Michigan game areas being closed to riding. They confuse cause and effect, and they feel that if we establish a public motorcycle trail, then all other facilities will be closed automatically. This is like my 4-year-old niece who went to her parents one day and said ‘Listen, this house is getting pretty old. When will the firemen come and burn it down?’ ”

In the beginning it was the failure of other motorcyclists to apply any real problem-solving ability to their situation that pushed Mel and a few friends into forming the CCCM. Back in 1967 Mel had gotten into a motorcycle club in the Lansing area and had found out the hard way about what public prejudice can do to bikers. When the neighbors started to complain about the club’s scrambles track the club went to the local zoning board for a permit, only to be turned down flat solely on the basis of the wild stories these neighbors told the board.

That most bikers could not deal effectively with this public prejudice showed up clearly for Mel in June of 1967. After scheduling and laying out an enduro using some state land in the Lansing area, this same club was told by the people managing the land to use a particular route. “They said ‘No, we won’t, because there are no rules that say we have to.’ This was in June of 1967; in October of 1967 the Michigan Department of Natural Resources published the new rules for the game areas in all of southern Michigan that prohibited the use of off-road vehicles. I always figured that it was that particular event where we actually were in contact with the people who controlled that land and refused to comply with their recommendations that precipitated the making of those rules.”

With the handwriting on the wall like this and no solutions coming from other motorcyclists, Mel and a couple of friends felt compelled to take steps of their own. “Ed Graham and his wife and I sat down over a cup of coffee and decided ‘Well, we know we’ll be sorry but....’ and made up our minds to start a statewide association of trail riders.” The name came very logically: “We decided that in order to catch the attention of the people who do know what conservation is all about we’d go that way. Ultimately those are the people you’re going to have to convince.

“True to our low-key tradition we didn’t start out by forming a club with a lot of hoopla, we started out by working on a trail, and just circulating a charter for people who were interested

to sign. Eventually in the Fall of 1968 we had our organizational meeting, but in the Summer of ’68 we worked on the first concept of the Pere Marquette Cycle Trail, 200 miles in the Mainstee National Forest. I just got a map that showed all the public lands in Michigan and said ‘This is the densest over here, let’s start here.’ ”

It’s not that simple, of course. Why a single long trail? And how does your mind get from 200 miles in the Manistee National Forest to that alluring, ambitious 800 miles all up and down the state of Michigan? How it happened comes out in pieces as you talk to Mel Lili; decisions were made and things happened that led almost unconsciously to The Trail. There was the Shore-toShore Hiking Trail, a path across the state developed between 1960 and 1964 by hikers and horsemen, so the analogy was part of it. The question of combating that public prejudice comes into it, too: “What do you do to demonstrate to the greatest number of people that motorcycles really have a right to ride off the road? The best thing is an established public trail with a sign at every road that it crosses with a motorcycle emblem on it that explains without too many words that motorcycles belong here. If we get a long trail with a sign at every road there will be hundreds of thousands that will see those signs, and we can’t afford any other means to reach them. So that’s part of the concept of the long public trail, is to get that idea across that motorcycles have a right to be here, too.”

Then there’s the matter of getting the use of the land. The U.S. Forest Service had been very receptive to the club’s proposal for the 200 miles but the bad experience with the state of Michigan in the case of the Lansing club’s enduro and the subsequent closure of the state game areas made prospects look anything but bright. To work on this angle the newly formed club came up with what Mel calls “the master stroke.” “We wrote a bill for the Legislature to establish a trail system. It was paraphrased after the National Trail Systems Act of 1968, which set up the scenic and recreational trails that the Bureau of Outdoor Recreation, the Department of Agriculture, and the Bureau of Land Management are supposed to be developing even yet. We got a copy of Trails for America (the BOR report on trails and trail development nationwide), we got a copy of the act, we paraphrased the act in a state-level bill directing the Department of Natural Resources to establish a statewide system of motorcycle trails.” This bill ended up as a resolution passed in May of 1969 that directed the DNR to develop motorcycle trails as multiple-use trails, but gave them no money for it. “It took care of the needs of the moment, which we had created by introducing the bill, and actually accomplished more than we could have accomplished any other way. I thought it was a pretty good deal all the way around,” Mel says.

The real clincher came when the club wanted to connect up two sections of the 200-mile Manistee National Forest trail by routing it through the Pere Marquette State Forest. Without much hope they arranged a meeting with the State Forestry Division, and were flabbergasted when the District Forester showed up and turned out to be all for it. “His first response was, ‘Well, if you want to go through the Pere Marquette State Forest why don’t you just go ahead and follow the snowmobile trails that we’ve already got laid out?’ The snowmobile trail went through a certain little campground, and he said ‘We’ve been thinking of closing up that campground because it hasn’t been used, but we kept it open for snowmobiles in wintertime, and maybe we can turn it into a motorcycle camp in the summer time.’ With that kind of acceptance it just set the ball to rolling.”

The idea for a project like the Marquette Trail is basically an imaginative act, not a rational one; but it was the reality of state cooperation on Michigan’s extensive system of public land that really turned the club’s minds loose. It started out as a sketch map: “I just gathered all the maps that I could get of the public lands in the state and laid out a trail in my imagination and published it on an 8V2XII sheet and labelled it ‘The Pere Marquette Cycle Trail, Approved and Proposed,’ and showed the little bit of it that was approved and the rest of it that was proposed,” says Mel. The club has been working on transferring the line from that sheet of paper to the ground ever since.

The magnitude of it doesn’t really hit you until you get out on a bike, and realize that those orange markers will lead you about as far as you’ll ever want to go on a motorcycle, through more countryside than most people will see in a lifetime. It’s partly the open-endedness of these long trails that does it, the exhilarating sense that you can go on forever through constantly changing, constantly new territory. I keep telling my conservationist acquaintances that trail riding is an intensely sensual, physical experience, and they never quite believe me, but you can certainly feel it up here as that smooth beaten path unreels in front of you and you drink in the sight and feeling of the rolling terrain, the luminous woods, the sudden open views across fields, the old roads that meander their way across the land.

We ride 90 miles on Saturday, striking out north and east from the small town of Mancelona. The billowing cloudbank on the horizon in the morning sweeps across the sky, bringing a raw northwest wind, rain showers, and in the late afternoon an extraordinary storm of sleet while the sun is shining. The return side on the road is frigid, but it can’t be helped; this trail is laid out to cover ground, not to run in nice neat loops that dump you back at your starting point with computerized efficiency.

On Sunday we ride with Mel. It has snowed lightly overnight, and the number of riders on the Color Tour is down from about 250 to 180. The weather remains cold, but it has cleared and the bright sunshine will make the snow disappear quickly. Following what has to be the world’s most complete route sheet (besides turns and mileages it has compass bearings, turns not to take, and an excellent sketch map), we head south on The Trail, turning quickly off the dirt road into a slippery single-track trail through the woods. Mel’s right leg has been rigid since he was 19, so he has equipped his Yamaha with a padded leg rest clamped to the right frame tube in front of the engine, and has the rear brake on the left along with the shift lever. He rides sitting down, the stiff leg stretched out comfortably on the rest.

“When the Japanese lightweights showed up, I very quickly found that I could go farther in the woods than most naturalists are willing to go on foot. That’s where I really found the enjoyment, in being able to extend my capabilities with a machine. I can’t hike very far, and I can’t even sit on a horse, but I’ll ride about as far on a motorcycle as anybody else. With a padded leg rest it’s more comfortable than riding in a car—there’s no room in a car and there’s all outdoors on a bike.” Mel uses his handicap as an example of the fact that you can trail ride without being reckless and irresponsible: “This kind of gets a little different concept across to them, that you can travel out on a motorcycle without being a hero rider.”

There are fewer hills and tight woods sections on this part of The Trail; instead we get miles of open sand roads through flat pine woods, old roads, and disused fields where the route wanders by the elm trees marking what was once somebody’s front yard. Mel has a feel for The Trail that you only get when you’ve helped to form it and it has become a part of you. Passing through an open area dotted with weathered stumps, he stops and explains that this is a famous spot—it seems that the virgin timber was clearcut, and for some reason nothing but grass has grown here since. You come to know the land in this way when you’ve worked on a trail, and you feel a little sorry for the people who will never do anything but ride through it. This is part of the reason Mel stops to help everyone—a man who has bruised his foot, a woman who needs help in figuring out how to ride down a steep, sandy hill (while her husband waits impatiently at the bottom, and Mel quietly explains just how to do it), a man and wife on shiny new matched Husqvarnas (he’s run out of gas and they’ve had to siphon some out of her tank).

Mel is obviously pleased to have so many people enjoying what the club has been able to do. One of the reasons these Trail Tours were started was to acquaint people with the different parts of the Marquette Trail as they grew. But he won’t ignore the future, either— “This is something that can’t go on forever,” he says as he looks around at the crowded parking area after the ride. In common with most other people who have thought seriously about the future of trail riding, he recognizes that the increasing numbers of people using this trail will make the environmental impact of large groups of people using small sections of it over a short period of time unacceptable. Large group rides like this may become a thing of the past.

He is equally sensitive to the imaginative push The Trail has supplied to the club: “When we run out of development I don’t know what the effect is going to be on the organization. When the Trail is finished the club may be in serious trouble.” The necessary maintenance will remain, of course, but that openended sense of exploration will be gone: “What’s romantic about putting up 5000 markers a year that were put up last year?” It may soon be a serious question.

An unhappy irony is the fact that Mel will not be around to see The Trail completed—his company is moving him to Arkansas. Meanwhile, trail work continues, the club’s rider training schools continue, an inheritance from a program Mel’s fellow club founder Ed Graham started in Lansing in 1967, and a motorcycle safety conference, an outgrowth of the rider training program. Mel sees the safety conference as another way of confronting a problem clearly and solving it, in this case the problem of developing a statistical base for understanding motorcycle accidents.

Mel is mostly indifferent to recognition of what the Cycle Conservation Club has been able to do. “The people who are seriously working on trails wouldn’t see it if they did get public recognition in print,” he says, “unless perhaps a friend showed it to them. Then they might read it. It seems to me that the problems involved are clear enough that anyone who gets seriously into it can see the solutions.” For Mel, you simply analyze the problem and work your way quietly to a solution. It sounds too simplistic to be effective— until you ride the Pere Marquette Cycle Trail.