OLIVE DRAB...

Frederick L. Klaiss

Or, Legend Of The War Surplus Cycle

WE'D ALL HEARD the stories. A friend had a cousin who knew a guy who could get war surplus Harleys for $75 each. The catch was that the motorcycles were sold only in lots of 10 each.

While everyone wanted a big bike he could buy for peanuts, there was no ten of us could scrape up enough cash at the same time. And if, by some miraculous reason, the money was available—why then, the friend’s cousin’s friend was not.

No one had actually seen the bikes, or knew the location of the surplus company selling them, or knew anyone in the flesh who owned one. The war surplus bargains became the Flying Dutchman Mine, Shangri-la, El Dorado’s treasure. More than a myth, these bikes were legend.

So no one got the Harleys. But through the years the rumors persisted. “A friend at the shop bought a surplus Indian. Only problem is, it’s in hundreds of pieces. But when he gets it together....”

We listened to the stories, nodded sagely, felt a twinge of sadness for what might have been and exchanged the dream for reality. There were no war surplus bikes.

Then, two years ago, a small classified ad in a Cleveland newspaper stirred old memories. A Buffalo, N.Y., surplus company offered crated ex-Canadian Air Force Triumph motorcycles. For Sale. On Hand. Ready for immediate delivery. Wow! Jackpot!

Aside from an address, the notice provided few details. The bikes were rigid frame, 500cc Twins with telescopic forks. Further enlightenment awaited the reply to a hastily scribbled note dispatched to Buffalo.

The answer was almost immediate. The motorcycles were built by Triumph in 1957 to Canadian War Office specifications. They had been assembled in England, ridden an average of 20 road test miles, partially disassembled and crated for shipment to Canada.

Once in the New World, the bikes languished in a government warehouse for more than a decade. They had been almost obsolete in 1957 and the years only emphasized their military unworthiness. But they were new Triumphs, still crated and wrapped, cosmoline still protecting vital working parts.

A few specification pages, photocopied from the original “Air Ministry User’s Handbook,” clinched the sale. H m m m....

PERFORMANCE

Recommended average safe speed (cross-country), 20 mph (32 kph); maximum gradient climbable (firm dry surface), 1 in 2; range of action on road (average speed 30 mph), 250 miles (400 kilom.).

TURNING CIRCLE

Left and right lock, 8 ft., 6 in. (2.7 metres).

NETT POWER/GROSS WEIGHT RATIO

67 bhp per ton.

WHEELS AND TYRES

Rim size, WM2. 19 in. front, WM3. 19 in. rear; tyre size, 3.25-19 front, 4.00-19 rear.

“Nett power...? Tyres...?” Hot damn, this is a foreign bike. An old V-Twin might do for the average road cowboy, but this rider had class. It was owning a Jaguar, a Nikon, a Garrard. Be the first on your block....

ENGINE

Type, vertical, parallel twin-cylinder, air-cooled; maximum bhp at clutch, 16.8.

Hold it right there, Jack. 16.8 maximum bhp. That’s less than Japanese two-strokes with one-third the displacement output. But then this isn’t some pressed-steel ring-ding-ding scooter with spider tires and a bastardized look about it.

This is a thoroughbred, assembled with the utmost care of Old World craftsmanship. Of course it was detuned for use on low-grade motor pool gasoline. The side-valve Twin offered torque, not horsepower. Being built to military specifications, it would last forever.

What if the bikes were rusted, damaged or incomplete? I’d examine the merchandise before laying down hard earned cash. What about parts for a 13-year-old relic? The thought never entered my mind.

Arrival of the letter coincided with a planned vacation to Toronto, so a sidejaunt to downtown Buffalo was quickly arranged.

Through a glass door fogged by years of grime, the shape of a motorcycle loomed in the dingy warehouse. But the door was locked and there was no sign of workmen about. After a futile pounding on the door frame I prepared to depart. My schedule allowed no time to return another day.

Another chapter in the Myth of the Surplus Motorcycles had been written. I’d come close enough to smell the gasoline and hot oil, but that was all. It would make a good story, even if ownership had eluded me.

Then a hand-lettered sign and a well-worn buzzer button high on the door sill caught my eye. “Ring bell for service.” No sound was heard but within a few seconds a man appeared.

“Yes, we’ve the motorcycles,” he said with a slight Canadian/English accent. “The one on the floor has just been assembled.”

The bike, looking new and shiny, was different but not disappointing. Instead of a Jaguar, on its centerstand sat a workhorse. I suddenly had a vision....

Its rear wheel kicking a roostertail of sand, courier Errol Flynn speeds his Triumph 500 to the entrance of a sandbagged bunker, dismounts and removes a message case from the pannier frame. He hurriedly asks directions of a sentry and rushes to Colonel David Niven, head of Allied Forces pursuing the Desert Fox across Africa.

“Sir,” he pants. “I have urgent news.... ”

No—this Triumph was more than a workhorse. It was an antique, a bloody war trophy.

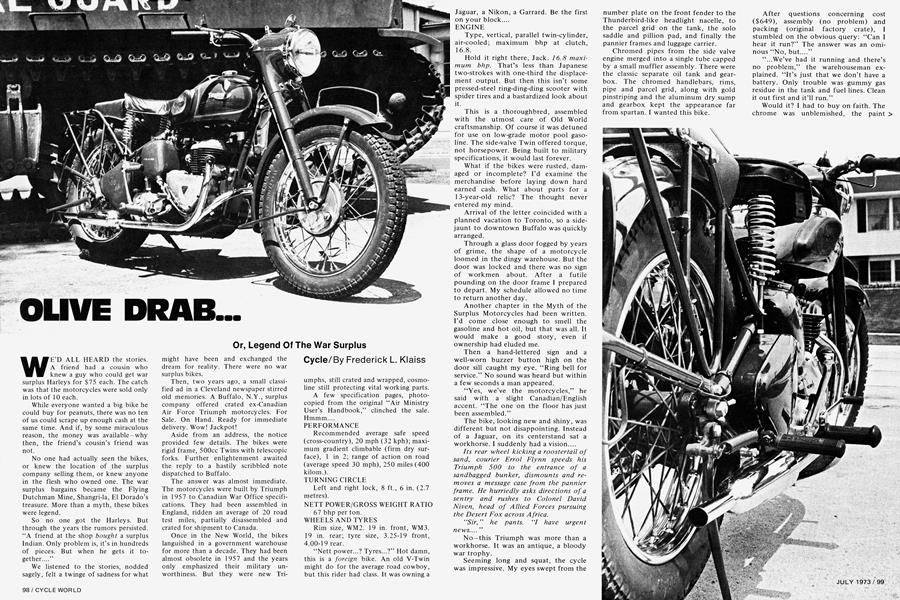

Seeming long and squat, the cycle was impressive. My eyes swept from the

number plate on the front fender to the Thunderbird-like headlight nacelle, to the parcel grid on the tank, the solo saddle and pillion pad, and finally the pannier frames and luggage carrier.

Chromed pipes from the side valve engine merged into a single tube capped by a small muffler assembly. There were the classic separate oil tank and gearbox. The chromed handlebars, rims, pipe and parcel grid, along with gold pinstriping and the aluminum dry sump and gearbox kept the appearance far from spartan. I wanted this bike.

After questions concerning cost ($649), assembly (no problem) and packing (original factory crate), I stumbled on the obvious query: “Can I hear it run?” The answer was an ominous “No, but....”

“...We’ve had it running and there’s no problem,” the warehouseman explained. “It’s just that we don’t have a battery. Only trouble was gummy gas residue in the tank and fuel lines. Clean it out first and it’ll run.”

Would it? I had to buy on faith. The chrome was unblemished, the paint > shiny, the leather immaculate and the rubber like new. I’d chance it.

Completing the vacation, I returned to Cleveland and exchanged my twoseat roadster for a four-door sedan, rental trailer, father and two younger cousins.

The trip to Buffalo took several hours; the sale only a few minutes. After the cashier’s check changed hands, a wooden packing box entered the trailer via a fork lift truck. We departed, but not before claiming a British

tanker’s helmet as a war trophy. The brimmed steel pot seemed an appropriate companion for the aging cycle.

Back in Cleveland the crate was immediately opened. Things looked good so far. The engine, drive train and rear wheel were completely assembled in the frame. Tires were mounted with air still in them. Nothing seemed missing.

To complete the cycle, the front wheel had to be mounted in the forks, the headlight nacelle assembled and the fork, with loose ball bearings, fastened to the frame head. All wiring must be properly connected. And, of course, the seat, pillion pad, exhaust pipe, muffler and numerous smaller items had to be installed. It seemed time-consuming, but not impossible.

While there were no assembly instructions, the “User’s Handbook” provided valuable construction tips. Only one hitch developed. Mounting the fork with loose ball bearings was more than a two-man operation, but, with liberal applications of grease on the races and time out to retrieve numerous dropped balls, it slipped on. We had triumphed over British engineering.

The warehouseman didn’t lie. There was much gas residue in the tank, lines and, probably, the carburetor. The fuel lines were disconnected, the shut-off valves dismantled and the tank soaked in Gumout. The carburetor went untouched.

Triumph had shipped the bike without engine oil but had left all other fluids intact. To be safe, I replaced the oil in the chaincase, gearbox and front forks.

According to doting owners, all Triumphs start immediately, but I anticipated an exhausting ritual before this bike kicked to life. It had been immobile for 13 years and the carburetor, ignition timing and plugs were not checked or adjusted.

I’d installed a replacement battery and now, gingerly, as though working with a priceless antique, I ran through the starting procedure. Open fuel valve, push choke lever fully forward, put transmission in neutral, work starter to draw gas into carburetor. Then, turning the switch to “Ign” I put my full weight on the kick lever. As expected, nothing happened. Then came the miracle. After two more kicks I heard a heartening pop and, on the next try, the old engine sputtered to life. It sat there happily, if erratically, idling away.

Mounted on the bike, revving the throttle, dreaming of the open road, I suddenly paused. No vehicle title accompanied the cycle. I had a valid bill of sale, but a sinking feeling told me this would not be enough to obtain Ohio registration and plates. Hesitantly I phoned the registrar and inquired.

“Where did you buy the motorcycle?”

“New York.”

“You need the New York title.”

“It was never titled in New York. It’s Canadian surplus.”

“Then you need Canadian papers. How did you import it if you don’t hold title?”

“It was never titled in Canada. I have a valid bill of sale from the New York agent of the Canadian seller. The bike was never assembled or run on a public road. It’s a new bike.”

“I thought you said it was made in

1957.”

“It was.”

“Then how can it be new?”

I gave up. A long distance phone call to the head of the surplus company in Toronto gave me assurance that all necessary papers would be provided. There was no title, but I was told bills of sale from all previous owners, including the Canadian government, would be sufficient. They weren’t.

Several days later, armed with photocopies of the War Department bill of sale, an invoice from the original wholesaler, receipt from another dealer and, finally, my bill of sale, 1 descended on the deputy registrar.

We repeated our telephone patter. Satisfied after examining the photocopies, he prepared to type an Ohio title. Then his boss ambled over to answer a question of procedure and eyed me suspiciously. No one would register a questionable vehicle while he was in charge.

“Why don’t you have a New York title?”

We ran through the routine again while I mumbled a little hysterically. Apparently no one registers surplus motorcycles.

The duo decided my Triumph could not be registered without a New York Department of Motor Vehicles notarized form authorizing sale. Another phone call to Toronto and it was in the mail.

Meanwhile the bike needed an Ohio inspection. Plates would not be issued without one and it’s illegal to ride without plates. It was suggested, not kindly, that I rent a trailer for the quarter-mile trip to the inspection station. Fed up with the bureaucracy, I rode without plates down a back road to the station. The inspector noted the engine serial number (a 30-sec. procedure) and I returned without incident.

Armed with the New York DMV form and inspection certificate, I again faced the registrar. There I learned Ohio law requires the frame number, not engine number, be registered. Fortunately the numbers match and the registrar accepted my papers. Perhaps worn down by my persistence, he issued the title. I paid the state sales tax and bought number plates. Legal at last!

On the street I found my Triumph ran, and ran well. Fifty mph was the recommended top speed for the first 1000 miles and it was hard to hold that limit. Actual top is close to 75.

The engine had a misfire at higher speeds but a thorough carburetor cleaning ended the problem. The timing was checked—on the button. Sure it leaks oil. What old Triumph, especially a non-unit construction Twin, doesn’t? All seals and gaskets appeared sound.

I immediately added a rear view mirror, the only modification from stock. Other than gas, oil and grease, my only expense has been for a compression release cable. The lead ball end separated from the cable on the original. The Japanese replacement battery is smaller than it should be but entirely satisfactory.

The bike is ideal for short rides on smooth surfaces, though the rigid rear end precludes extended touring for me. The huge Dunlops with universal tread hold the dirt like glue but it’s too nice a machine to risk a spill.

If this Triumph was completely inoperative, it would still be a great conversation piece. Other motorcyclists either ignore it or blow their minds.

Riders of Japanese bikes refuse to admit it exists. Most are too young to appreciate the “classic” lines. They want nothing to do with a machine that’s slow, requires constant preventive maintenance, drips oil copiously and vibrates.

Triumph owners wave and chopper riders are surprisingly interested, perhaps because of the rigid frame. Older riders can relive much of their past in this bike’s styling. This is one motorcycle “built like they used to be.” Because that’s when it was made.

I’ve relayed the address of the importer numerous times but I’ve never seen a similar cycle on the street. Maybe I was lucky; perhaps the rest of the lot were junk.

Many persons stop me for a ride, want to purchase the machine, or want to just gossip.

“Triumph’s not bad,” they say. “But I’ve heard of surplus Harleys for $75 each and when I raise the cash....”