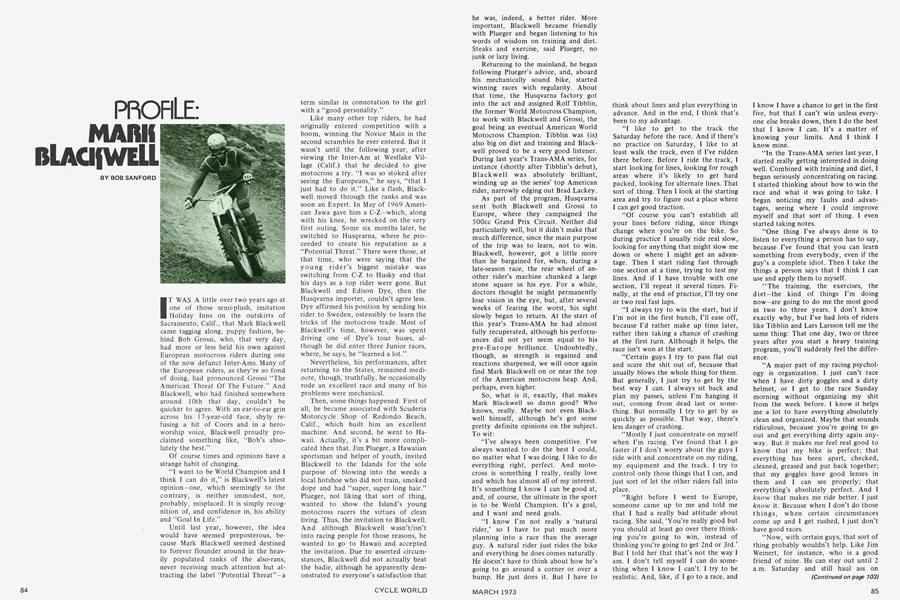

PROFILE:

MARK BLACKWELL

BOB SANFORD

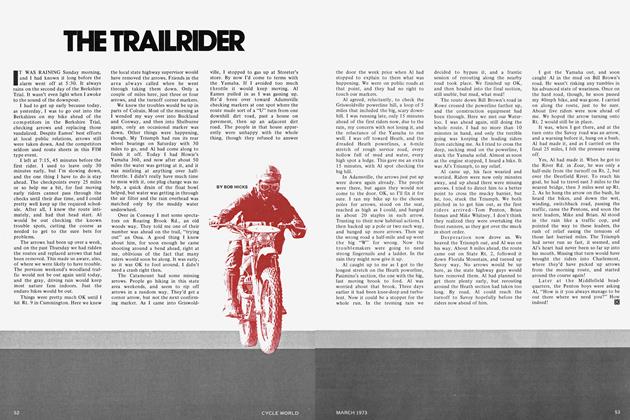

IT WAS A little over two years ago at one of those semi-plush, imitation Holiday Inns on the outskirts of Sacramento, Calif., that Mark Blackwell came tagging along, puppy fashion, behind Bob Grossi, who, that very day, had more or less held his own against European motocross riders during one of the now defunct Inter-Ams. Many of the European riders, as they’re so fond of doing, had pronounced Grossi “The American Threat Of The Future.” And Blackwell, who had finished somewhere around 10th that day, couldn’t be quicker to agree. With an ear-to-ear grin across his 17-year-old face, shyly refusing a hit of Coors and in a hero-worship voice, Blackwell proudly proclaimed something like, “Bob’s absolutely the best.”

Of course times and opinions have a strange habit of changing.

“I want to be World Champion and I think I can do it,” is Blackwell’s latest opinion—one, which seemingly to the contrary, is neither immodest, nor, probably, misplaced. It is simply recognition of, and confidence in, his ability and “Goal In Life.”

Until last year, however, the idea would have seemed preposterous, because Mark Blackwell seemed destined to forever flounder around in the heavily populated ranks of the also-rans, never receiving much attention but attracting the label “Potential Threat”—a

term similar in connotation to the girl with a “good personality.”

Like many other top riders, he had originally entered competition with a boom, winning the Novice Main in the second scrambles he ever entered. But it wasn’t until the following year, after viewing the Inter-Am at Westlake Village (Calif.) that he decided to give motocross a try. “I was so stoked after seeing the Europeans,” he says, “that I just had to do it.” Like a flash, Blackwell moved through the ranks and was soon an Expert. In May of 1969 American Jawa gave him a C-Z—which, along with his knee, he wrecked on the very first outing. Some six months later, he switched to Husqvarna, where he proceeded to create his reputation as a “Potential Threat.” There were those, at that time, who were saying that the young rider’s biggest mistake was switching from C-Z to Husky and that his days as a top rider were gone. But Blackwell and Edison Dye, then the Husqvarna importer, couldn’t agree less. Dye affirmed his position by sending his rider to Sweden, ostensibly to learn the tricks of the motocross trade. Most of Blackwell’s time, however, was spent driving one of Dye’s tour buses, although he did enter three Junior races, where, he says, he “learned a lot.”

Nevertheless, his performances, after returning to the States, remained mediocre, though, truthfully, he occasionally rode an excellent race and many of his problems were mechanical.

Then, some things happened: First of all, he became associated with Scuderia Motorcycle Shop of Redondo Beach, Calif., which built him an excellent machine. And second, he went to Hawaii. Actually, it’s a bit more complicated then that. Jim Plueger, a Hawaiian sportsman and helper of youth, invited Blackwell to the Islands for the sole purpose of blowing into the weeds a local hotshoe who did not train, smoked dope and had “super, super long hair.” Plueger, not liking that sort of thing, wanted to show the Island’s young motocross racers the virtues of clean living. Thus, the invitation to Blackwell. And although Blackwell wasn’t/isn’t into racing people for those reasons, he wanted to go to Hawaii and accepted the invitation. Due to assorted circumstances, Blackwell did not actually beat the badie, although he apparently demonstrated to everyone’s satisfaction that he was, indeed, a better rider. More important, Blackwell became friendly with Plueger and began listening to his words of wisdom on training and diet. Steaks and exercise, said Plueger, no junk or lazy living.

Returning to the mainland, he began following Plueger’s advice, and, aboard his mechanically sound bike, started winning races with regularity. About that time, the Husqvarna factory got into the act and assigned Rolf Tibblin, the former World Motocross Champion, to work with Blackwell and Grossi, the goal being an eventual American World Motocross Champion. Tibblin was (is) also big on diet and training and Blackwell proved to be a very good listener. During last year’s Trans-AMA series, for instance (shortly after Tibblin’s debut), Blackwell was absolutely brilliant, winding up as the series’ top American rider, narrowly edging out Brad Lackey.

As part of the program, Husqvarna sent both Blackwell and Grossi to Europe, where they campaigned the 500cc Grand Prix Circuit. Neither did particularly well, but it didn’t make that much difference, since the main purpose of the trip was to learn, not to win. Blackwell, however, got a little more than he bargained for, when, during a late-season race, the rear wheel of another rider’s machine chunked a large stone square in his eye. For a while, doctors thought he might permanently lose vision in the eye, but, after several weeks of fearing the worst, his sight slowly began to return. At the start of this year’s Trans-AMA he had almost fully recuperated, although his performances did not yet seem equal to his pre-Europe brilliance. Undoubtedly, though, as strength is regained and reactions sharpened, we will once again find Mark Blackwell on or near the top of the American motocross heap. And, perhaps, even higher.

So, what is it, exactly, that makes Mark Blackwell so damn good? Who knows, really. Maybe not even Blackwell himself, although he’s got some pretty definite opinions on the subject. To wit:

“Eve always been competitive. I’ve always wanted to do the best I could, no matter what I was doing. I like to do everything right, perfect. And motocross is something I really, really love and which has almost all of my interest. It’s something I know I can be good at, and, of course, the ultimate in the sport is to be World Champion. It’s a goal, and I want and need goals.

“I know I’m not really a ‘natural rider,’ so I have to put much more planning into a race than the average guy. A natural rider just rides the bike and everything he does comes naturally. He doesn’t have to think about how he’s going to go around a corner or over a bump. He just does it. But I have to think about lines and plan everything in advance. And in the end, I think that’s been to my advantage.

“I like to get to the track the Saturday before the race. And if there’s no practice on Saturday, I like to at least walk the track, even if I’ve ridden there before. Before I ride the track, I start looking for lines, looking for rough areas where it’s likely to get hard packed, looking for alternate lines. That sort of thing. Then I look at the starting area and try to figure out a place where I can get good traction.

“Of course you can’t establish all your lines before riding, since things change when you’re on the bike. So during practice I usually ride real slow, looking for anything that might slow me down or where I might get an advantage. Then I start riding fast through one section at a time, trying to test my lines. And if I have trouble with one section, I’ll repeat it several times. Finally, at the end of practice, I’ll try one or two real fast laps.

“I always try to win the start, but if I’m not in the first bunch, I’ll ease off, because I’d rather make up time later, rather then taking a chance of crashing at the first turn. Although it helps, the race isn’t won at the start.

“Certain guys I try to pass flat out and scare the shit out of, because that usually blows the whole thing for them. But generally, I just try to get by the best way I can. I always sit back and plan my passes, unless I’m hanging it out, coming from dead last or something. But normally I try to get by as quickly as possible. That way, there’s less danger of crashing.

“Mostly I just concentrate on myself when I’m racing. I’ve found that I go faster if I don’t worry about the guys I ride with and concentrate on my riding, my equipment and the track. I try to control only those things that I can, and just sort of let the other riders fall into place.

“Right before I went to Europe, someone came up to me and told me that I had a really bad attitude about racing. She said, ‘You’re really good but you should at least go over there thinking you’re going to win, instead of thinking you’re going to get 2nd or 3rd.’ But I told her that that’s not the way I am. I don’t tell myself I can do something when I know I can’t. I try to be realistic. And, like, if I go to a race, and I know I have a chance to get in the first five, but that I can’t win unless everyone else breaks down, then I do the best that I know I can. It’s a matter of knowing your limits. And I think I know mine.

“In the Trans-AMA series last year, I started really getting interested in doing well. Combined with training and diet, I began seriously concentrating on racing. I started thinking about how to win the race and what it was going to take. I began noticing my faults and advantages, seeing where I could improve myself and that sort of thing. I even started taking notes.

“One thing I’ve always done is to listen to everything a person has to say, because I’ve found that you can learn something from everybody, even if the guy’s a complete idiot. Then I take the things a person says that I think I can use and apply them to myself.

“The training, the exercises, the diet-the kind of things I’m doing now—are going to do me the most good in two to three years. I don’t know exactly why, but I’ve had lots of riders like Tibblin and Lars Larsson tell me the same thing: That one day, two or three years after you start a heavy training program, you’ll suddenly feel the difference.

“A major part of my racing psychology is organization. I just can’t race when I have dirty goggles and a dirty helmet, or I get to the race Sunday morning without organizing my shit from the week before. I know it helps me a lot to have everything absolutely clean and organized. Maybe that sounds ridiculous, because you’re going to go out and get everything dirty again anyway. But it makes me feel real good to know that my bike is perfect; that everything has been apart, checked, cleaned, greased and put back together; that my goggles have good lenses in them and I can see properly; that everything’s absolutely perfect. And I know that makes me ride better. I just know it. Because when I don’t do those things, when certain circumstances come up and I get rushed, I just don’t have good races.

“Now, with certain guys, that sort of thing probably wouldn’t help. Like Jim Weinert, for instance, who is a good friend of mine. He can stay out until 2 a.m. Saturday and still haul ass on Sunday. But I can’t do that and I won’t do that. I like to know where I am and what I’m doing all the time, whether it’s Tuesday or Wednesday or Saturday. I like to be scheduled and my mind crystal clear.

(Continued on page 103)

Continued from page 85

“Before I went to Europe this year I told myself, ‘You’re going to be losing a lot, but that’s the price you pay to learn and improve.’ The whole thing is actually a gamble. You’re gambling a temporary loss now against a large gain in the future: Giving up something today, to become a better rider in a couple of years. And it’s worth it to me, because I want to eventually be World Champion.”

Of course, Mark Blackwell is more than an assortment of quotations. He is a mostly serious young man, less than two years out of high school. In many ways, he is surprisingly mature and independent, while, in still others, his age is betrayed. He is slightly naive but probably realistic; for instance, about the packaging he has done with his future. He knows what he wants, believes in it and is committed to its achievement. Yet, much of what he says sounds ever so slightly like a young boy’s “when I grow up I want to be a fireman” declaration.

He seems blessed with an abnormal amount of patience (at least, in a long-term sense) for an American 19year-old. And he probably trains as hard, if not harder, than any other top American motocross rider, although he was criticized by European riders for not taking his training seriously enough. To be sure, he has as much stamina, ability and know-how as any current U.S. motocross hotshoe. He is intelligent, quick learning and well-organized—qualities that are usually considered helpful for up-and-coming young motocross riders.

And, of more than a little import, he has a father that neither pushes nor ignores him. He is helped, one could surmize, to be independent.

Perhaps most important, he seems determined to be as good as possible at what he has chosen to do. His goal seems at least plausible, considering his talent, ability and so on. And he apparently sees what is necessary for attaining that goal and seems prepared and/or resigned to deal with the strain and time.

In the final analysis, Mark Blackwell could conceivably become the first American World Motocross Champion. But so could Brad Lackey. Or Marty Tripes. Or even the Schwinn-riding kid that lives down the block. 0