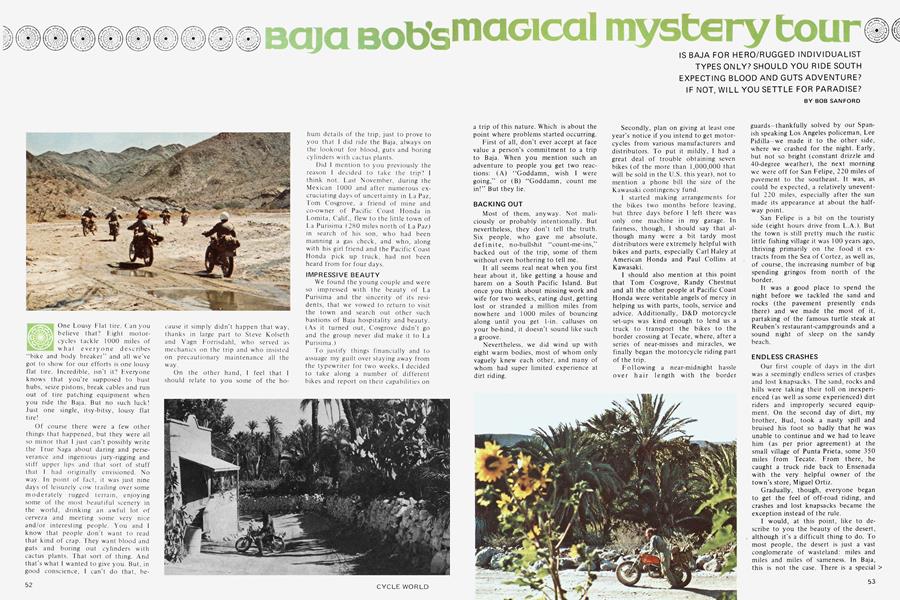

BAJA BOB'S MAGICAL MYSTERY TOUR

One Lousy Flat tire. Can you believe that? Eight motorcycles tackle 1000 miles of what everyone describes “bike and body breaker” and all we’ve got to show for our efforts is one lousy flat tire. Incredible, isn’t it? Everyone knows that you’re supposed to bust hubs, seize pistons, break cables and run out of tire patching equipment when you ride the Baja. But no such luck! Just one single, itsy-bitsy, lousy flat tire!

Of course there were a few other things that happened, but they were ail so minor that I just can’t possibly write the I rue Saga about daring and perseverance and ingenious jury-rigging and stiff upper lips and that sort of stuff that 1 had originally envisioned. No way. In point of fact, it was just nine days of leisurely cow trailing over some moderately rugged terrain, enjoying some of the most beautiful scenery in the world, drinking an awful lot of cerveza and meeting some very nice and/or interesting people. You and I know that people don’t want to read that kind of crap. They want blood and guts and boring out cylinders with cactus plants. That sort of thing. And that’s what 1 wanted to give you. But, in good conscience, I can’t do that, because it simply didn’t happen that way, thanks in large part to Steve Kolseth and Vagn Forrisdahl, who served as mechanics on the trip and who insisted on precautionary maintenance all the way.

On the other hand, I feel that I should relate to you some of the hohum details of the trip, just to prove to you that I did ride the Baja, always on the lookout for blood, guts and boring cylinders with cactus plants.

Did I mention to you previously the reason I decided to take the trip? 1 think not. Last November, during the Mexican 1000 and after numerous excruciating days of uncertainty in La Paz, lorn Cosgrove, a friend of mine and co-owner of Pacific Coast Honda in Lomita, Calif., flew to the little town of La Purísima (280 miles north of La Paz) in search of his son, who had been manning a gas check, and who, along with his girl friend and the Pacific Coast Honda pick up truck, had not been heard from for four days.

IMPRESSIVE BEAUTY

We found the young couple and were so impressed with the beauty of La Purísima and the sincerity of its residents, that we vowed to return to visit the town and search out other such bastions of Baja hospitality and beauty. (As it turned out, Cosgrove didn’t go and the group never did make it to La Purísima.)

To justify things financially and to assuage my guilt over staying away from the typewriter for two weeks, 1 decided to take along a number of different bikes and report on their capabilities on a trip of this nature. Which is about the point where problems started occurring.

IS BAJA FOR HERO/RUGGED INDIVIDUALIST TYPES ONLY? SHOULD YOU RIDE SOUTH EXPECTING BLOOD AND GUTS ADVENTURE? IF NOT, WILL YOU SETTLE FOR PARADISE?

BOB SANFORD

First of all, don’t ever accept at face value a person’s commitment to a trip to Baja. When you mention such an adventure to people you get two reactions: (A) “Goddamn, wish 1 were going,” or (B) “Goddamn, count me in!” But they lie.

BACKING OUT

Most of them, anyway. Not maliciously or probably intentionally. But nevertheless, they don’t tell the truth. Six people, who gave me absolute, definite, no-bullshit “count-me-ins,” backed out of the trip, some of them without even bothering to tell me.

It all seems real neat when you first hear about it, like getting a house and harem on a South Pacific Island. But once you think about missing work and wife for two weeks, eating dust, getting lost or stranded a million miles from nowhere and 1000 miles of bouncing along until you get 1-in. calluses on your be-hind, it doesn’t sound like such a groove.

Nevertheless, we did wind up with eight warm bodies, most of whom only vaguely knew each other, and many of whom had super limited experience at dirt riding.

Secondly, plan on giving at least one year’s notice if you intend to get motorcycles from various manufacturers and distributors. To put it mildly, I had a great deal of trouble obtaining seven bikes (of the more than 1,000,000 that will be sold in the U.S. this year), not to mention a phone bill the size of the Kawasaki contingency fund.

1 started making arrangements for the bikes two months before leaving, but three days before 1 left there was only one machine in my garage. In fairness, though, 1 should say that although many were a bit tardy most distributors were extremely helpful with bikes and parts, especially Carl Haley at American Honda and Paul Collins at Kawasaki.

1 should also mention at this point that Tom Cosgrove, Randy Chestnut and all the other people at Pacific Coast Honda were veritable angels of mercy in helping us with parts, tools, service and advice. Additionally, D&D motorcycle set-ups was kind enough to lend us a truck to transport the bikes to the border crossing at Tecate, where, after a series of near-misses and miracles, we finally began the motorcycle riding part of the trip.

Following a near-midnight hassle over hair length with the border guards—thankfully solved by our Spanish speaking Los Angeles policeman, Lee Pidilla-we made it to the other side, where we crashed for the night. Early, but not so bright (constant drizzle and 40-degree weather), the next morning we were off for San Felipe, 220 miles of pavement to the southeast. It was, as could be expected, a relatively uneventful 220 miles, especially after the sun made its appearance at about the halfway point.

San Felipe is a bit on the touristy side (eight hours drive from L.A.). But the town is still pretty much the rustic little fishing village it was 1 00 years ago, thriving primarily on the food it extracts from the Sea of Cortez, as well as, of course, the increasing number of big spending gringos from north of the border.

It was a good place to spend the night before we tackled the sand and rocks (the pavement presently ends there) and we made the most of it, partaking of the famous turtle steak at Reuben’s restaurant-campgrounds and a sound night of sleep on the sandy beach.

ENDLESS CRASHES

Our first couple of days in the dirt was a seemingly endless series of crashes and lost knapsacks. The sand, rocks and hills were taking their toll on inexperienced (as well as some experienced) dirt riders and improperly secured equipment. On the second day of dirt, my brother, Bud, took a nasty spill and bruised his foot so badly that he was unable to continue and we had to leave him (as per prior agreement) at the small village of Punta Prieta, some 350 miles from Tecate. From there, he caught a truck ride back to Ensenada with the very helpful owner of the town’s store, Miguel Ortiz.

Gradually, though, everyone began to get the feel of off-road riding, and crashes and lost knapsacks became the exception instead of the rule.

I would, at this point, like to describe to you the beauty of the desert, although it's a difficult thing to do. To most people, the desert is just a vast conglomerate of wasteland: miles and miles and miles of sameness. In Baja, this is not the case. There is a special > beauty to the desert that subtly changes from acre to acre.

In one area there are majestic mountains, covered with jagged rocks that are at least 1000 different shades of dark. And then, almost suddenly, you are riding through wall-to-wall giant cacti, sporadically dotted with splotches of red and white, where blossoms are trying to poke their way into the arid climate.

The desert is also giant gorges, where surface springs feed trickling streams that wind their way through miles of valley, providing water for the thousands of desert animals, as well as the large trees and plants along the banks. And the desert, in some areas, is multiton upon multi-ton of sand, artistically shaped by eons of wind into giant, smooth mounds of asymmetrical beauty. And at night, the desert is smogless skies with billions of stars you never knew existed winking down at you in your sleeping bag from millions of light years away. Plus more. Much, much more.

That’s the way it was. For five days, as we made our way past San Felipe, Papa Fernandez’ fishing camp, Punta Prieta, El Arco and finally into San Ignacio, where we discovered a relatively unknown oasis-paradise, and where the complexion of the trip changed considerably.

PARADISE DESCRIBED

I would hesitate in mentioning San Ignacio in a general travel magazine since much of its charm would undoubtedly disappear with the first heavy influx of tourists. The minute American tourists “discover” a place, honesty, sincerity and graciousness vanish and are replaced with hustlers, thieves, high prices and anti-American feelings. But it won’t make that much difference whether I mention the town or not, since the Mexican government plans to complete the road to La Paz within the next three years, virtually assuring thousands and thousands of tourists annually. Anyway, San Ignacio is still “pure,” because most travelers think that the handful of houses along the perimeter of this vast oasis of date palms is, in fact, the town itself. Actually, San Ignacio is nestled squarely in the middle of the oasis, about one mile of winding road off the main thoroughfare.

It’s really a sight to behold. Sitting like a giant, stone father at the head of the town is a 200-year-old Catholic mission, which faces the town square, currently undergoing renovation. Surrounding the square are the town’s businesses, with perhaps 200 neat family dwellings encircling the business district. Giant trees, some more than 100 ft. tall, dominate the town plaza and provide shade for the entire commercial area. And just about every vehicle you see-and there are lots of them-is a late model pick up truck, with all the accessories and a fresh coat of wax.

FRIENDLY TOWN

Prosperity runs rampant, thanks to the exportation of grapes and dates to the mainland of Mexico, which, as you may have surmised, is largely due to the abundance of water in the area.

The people there, we found, were extremely friendly and did not display the hostility and suspicion so common in border towns and other tourist traps. The Casa Leree is somewhat typical of the town’s attitude. For the last few years, Casa Leree has served as a hotelrestaurant for the town’s handful, yet ever increasing number, of tourists. Extra rooms in the house are used to bed visitors, and when these are full, cots are set up in the beautiful century-old grape arbor, where, incidentally, we ate breakfast beside the foot-wide stream that traverses the property. (We had made other sleeping arrangements before learning of Casa Leree.)

(Continued on page 90)

Continued from page 54

To our surprise, we were greeted with American slang from the fiftyish woman who waited on us. Rebecca Carrillo, it seems, was born at Casa Leree, but was raised in Van Nuys, Calif., and only recently returned to tend her soon-to-be 100-year-old mother, the matron of the Casa. Relatives from throughout Mexico were on hand for the matron’s birthday, and as pleasant and gracious as they all were, it would have been easy to stay there for at least 20 more years.

SPLITTING OF WAYS

But it was also in San Ignacio that we experienced some interpersonal problems. I don’t think it’s necessary to outline the particulars, except to say that they stemmed from differing attitudes, goals, ideals and opinions, which, it seems to me in retrospect, is something you must expect when near strangers, of differing backgrounds and ages, get together for a trip like this. After that, there were two factions within the group, one wanting to lounge along the way, the other wanting to ride hell-bent for leather into Ta Pa/.. Things finally came to a head two days later in Mulege, with the majority (4-3) voting to stay there for the night, and two of the dissenters opting to continue on to La Paz by themselves.

Am I glad we stayed in Mulege. The second neatest place in Baja. Mulege is located on the gulf side of the peninsula, about 300 road miles from La Paz. It, like San Ignacio, has an abundance of fresh water, as well as a jungle of palm trees.

BATHING IN THE BUFF

The neat thing, though, is that the water comes from a hot springs about two miles from the coast, which then flows in a lazy river down to the ocean. And there is nothing repeat, nothinglike bathing and swimming, sans clothes, in Mulege’s hot springs. Especially after a day of riding and eating dirt.

The town itself is rather typically Mexican (assuming there is such a thing), with a preponderance of adobe houses and businesses sitting along the edges of the numerous dirt streets. Mulege has been “discovered” by the Piper Cub Set, who fly in on weekends and spend their time browsing through the curio shops and cantinas, occasionally throwing a “buenas dias” at a villager slowly taking care of the day’s business.

It was in Mulege that we: (A) discovered Alfonso Cuesta and his Old Hacienda hotel, (B) met a very nice retired Mexican couple from Ensenada by the name of Fano, and (C) made our first, but certainly not last, contact with E.J. “Bosco” Christensen, a.k.a. Captain Zero, The Detroit Fox (pronounced DEE-troit), Super Star, The Gray Ghost and Bimbo, just to name a few.

(Continued on page 94)

Continued from page 90

THE BIG FISH

Good old Bosco. You remember Phil Harris, don’t you? Well, Bosco bears a striking, if slightly slimmer, resemblance to him, complete with wavy hair, ruddy complexion and a never-ending patter of slightly antiquated “jive” talk. (“Look out, baby, here come da DEE-troit fox.”) He owns a trucking company in Vancouver, Wash. (“We’re just big fish in a small pond, but we like it there.”), and he, his wife (“Been married 16 years, baby, and I don’t smoke my wife and she don’t smoke me.”) and six other people were on a two-airplane, month long, highly organized (“. . . 20 minutes flying time, then two days in Loreto, then . . . ”) vacation in Mexico (“These Mexican dudes really know how to live, don’t they?”).

Furthermore, he owns a DT-1 (“With the Gyt Kit. It’s more than the oF man can handle.”) and liked to talk about hikes (“. . . and the local hot shoes blew these National Number riders right into the weeds.”). Of course, some of his remarks were open to question. (“Been fishin’ down here seven years and only been skunked twice.”)

Then to another group two days later, “Been fishin’ down here seven years and never been skunked.” On the other hand, some of his remarks were not open to question (“I’m an obnoxious bastard, even when I’m not drinking.”). And he was that, all right, but a likeable obnoxious bastard just the same.

PLANE FOR BIKE

Anyway, we met Bosco and his crew at Alfonso’s Old Hacienda, ait attractive, 200-year-old structure in the* center of town that has been converted into a hotel, restaurant and bar, and where you can get a room, some class-A hospitality and three delicious meals for S 10 a day.

That evening, we were sitting around the courtyard, drinking Cuba Libres and listening to Captain Zero’s spiel about riding and how lucky we were to be taking a trip like this, when I suddenly had an idea. Bosco, I said. I’ve got a plan that will make your dreams come true. Why not, I suggested, let one of us go in the plane to Loreto (80 miles) tomorrow and you can ride the hike? Without hesitating, he snapped at the idea, and after a superb turtle steak dinner, we agreed to meet at the airport the following morning, where we would put Bosco aboard the Uusqvarna and Vagn Forrisdahl aboard the Cessna (or was it a Piper?).

(Continued on page 96)

Continued from page 94

Frankly, 1 didn’t expect him to follow through, but at the prescribed time, there he was, decked out in baby-blue lightweight denims, wing-tip cordovans and, for some reason, a white towel tied around his neck. Boots? Helmet? Naw, don’t need ’em. Never use ’em at home, anyway.

BOSCO LEADS

Practically from the minute we lett, Bosco jumped into the lead (“Not bad for an ol’ man, huh?”), and stayed there until he ran out of gas. That section, by the way, is where we learned that “washboard” roads just about double gas consumption, as Bosco’s Husky and Doug Parker’s Montesa ran out of gas a combined total of five times.

But we did finally make it (“Not bad for an ol’ man, huh? Just wait ’till you hear the lies I’m going to tell about this when I get home.” Plus, with a wink of the eye and a patronizing tone, “Thanks a lot for let tin’ the ol’ man stay out in front, fellas.”).

And that was Bosco, and, for all intents and purposes, our trip, as we zoomed the last 230 miles of pavement into La Paz the next day, followed a day later by our good friend Bosco, who was more than a little interested in obtaining one of those ostentacious patches that proclaims: Tijuana To La Taz Veteran Of The Road-CONQUISTA DOR.

We sat around La Paz for a couple of days, feeling closer to Tijuana than to San Ignacio or Mulege. Then, in groups of twos and threes, depending on how anxious we were to get back to the U.S. of A., we flew home, our bikes following a couple of weeks later on slow boat.

All in all, it was an extremely pleasant trip, even though we only had one lousy flat tire and no blood, guts or cactus plant cylinder boring. Maybe next year.

In some ways, the trip was easier than 1 expected; in other ways, more difficult. The terrain, for instance, is not all that rough. But there’s a hell of a lot of it. And we had no trouble at all buying gas along the way. But there’s not Can One of two-stroke oil on the whole peninsula-that I know about, at least. I’m sorry I didn’t get the blood and guts True Saga that 1 started out to get, but then, maybe 1 have a story here and don’t even know it.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsRound Up

SEPT 1971 1971 By Joe Parkhurst -

Letters

LettersLetters

SEPT 1971 1971 -

Departments

DepartmentsThe Service Dept

SEPT 1971 1971 By Jody Nicholas -

Departments

DepartmentsFeedback

SEPT 1971 1971 -

Technical, Etc.

Technical, Etc.Balancing the Mighty Multi

SEPT 1971 1971 By Gary Peters, Matt Coulson -

Features

FeaturesIt's A Steal

SEPT 1971 1971 By Joseph E. Bloggs