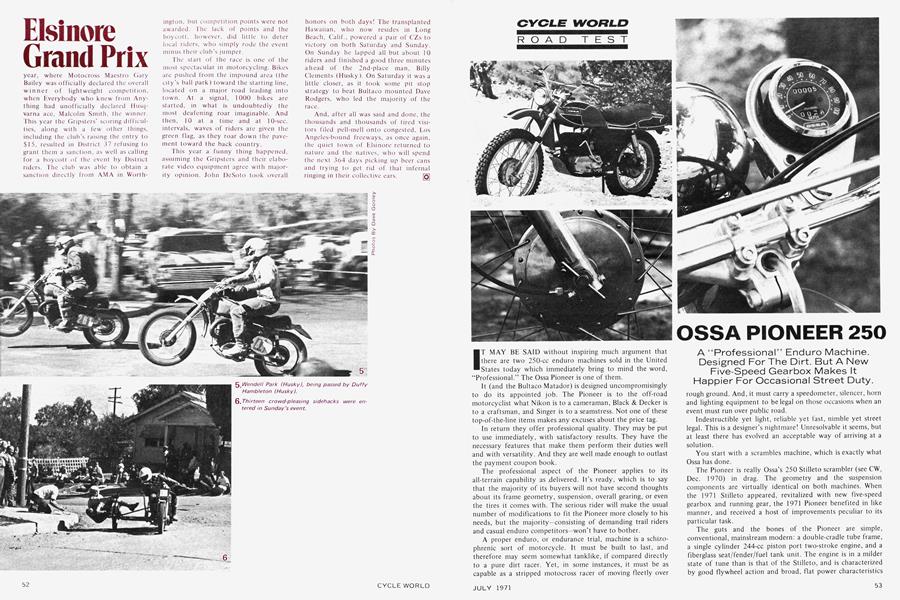

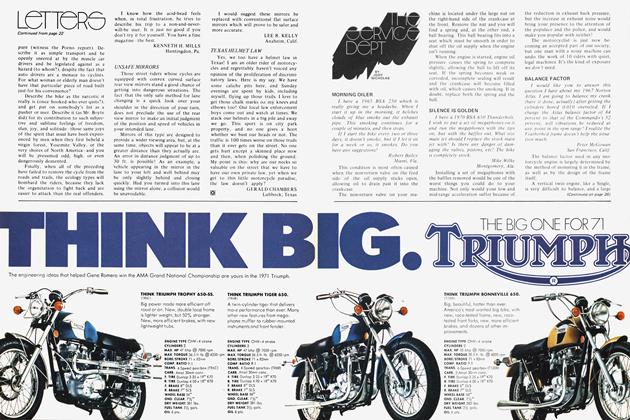

OSSA PIONEER 250

CYCLE WORLD ROAD TEST

A "Professional" Enduro Machine. Designed For The Dirt. But A New Five-Speed Gearbox Makes It Happier For Occasional Street Duty.

IT MAY BE SAID without inspiring much argument that there are two 250-cc enduro machines sold in the United States today which immediately bring to mind the word, "Professional." The Ossa Pioneer is one of them.

It (and the Bultaco Matador) is designed uncompromisingly to do its appointed job. The Pioneer is to the off-road motorcyclist what Nikon is to a cameraman. Black & Decker is to a craftsman, and Singer is to a seamstress. Not one of these top-of-the-line items makes any excuses about the price tag.

In return they offer professional quality. They may be put to use immediately, with satisfactory results. They have the necessary features that make them perform their duties well and with versatility. And they are well made enough to outlast the payment coupon book.

The professional aspect of the Pioneer applies to its all-terrain capability as .delivered. It’s ready, which is to say that the majority of its buyers will not have second thoughts about its frame geometry, suspension, overall gearing, or even the tires it comes with. The serious rider will make the usual number of modifications to fit the Pioneer more closely to his needs, but the majority—consisting of demanding trail riders and casual enduro competitors—won’t have to bother.

A proper enduro, or endurance trial, machine is a schizophrenic sort of motorcycle. It must be built to last, and therefore may seem somewhat tanklike, if compared directly to a pure dirt racer. Yet, in some instances, it must be as capable as a stripped motocross racer of moving fleetly over rough ground. And, it must carry a speedometer, silencer, horn and lighting equipment to be legal on those occasions when an event must run over public road.

Indestructible yet light, reliable yet fast, nimble yet street legal. This is a designer’s nightmare! Unresolvable it seems, but at least there has evolved an acceptable way of arriving at a solution.

You start with a scrambles machine, which is exactly what Ossa has done.

The Pioneer is really Ossa’s 250 Stilleto scrambler (see CW. Dec. 1970) in drag. The geometry and the suspension components are virtually identical on both machines. When the 1971 Stilleto appeared, revitalized with new five-speed gearbox and running gear, the 1971 Pioneer benefited in like manner, and received a host of improvements peculiar to its particular task.

The guts and the bones of the Pioneer are simple, conventional, mainstream modern: a double-cradle tube frame, a single cylinder 244-cc piston port two-stroke engine, and a fiberglass seat/fender/fuel tank unit. The engine is in a milder state of tune than is that of the Stilleto, and is characterized by good flywheel action and broad, flat power characteristics throughout the entire rpm range, from idle to peaking speed. This, and the longish Ossa wheelbase, conspire to make the Pioneer an exceptional hill climber, mud slogger, and top gear sandwash runner, as well as stable in bouncy going.

OSSA PIONEER

The new Pioneer seems to preserve several attributes which made the models of 1969 and 1970 pleasant machines to own. After break-in, for example, the machine seems to “consume” less spark plugs than you would normally expect of a two-stroke machine. Nor is the engine overly sensitive to altitude changes or indiscretions in mixing oil with fuel.

The '69 250 four-speed owned by one of our staffers is cleaned, that is to say hosed off, about six times yearly, although it is ridden about every other week, and the mechanical maintenance it receives is just about as cavalier. Recommended oil is Full Bore at 32:1, but the '69 has been subjected to such awesome sequences as Standard’s outboard motor oil 20:1, Bardahl VBA at 50:1, Blendzall at 28:1, Steen’s C at 20:1, ad nauseam, without emptying the tank between mixture changes. Except for that rather juicy bout with outboard oil, the ’69 ran quite well through all this cruelty, using only three B8E spark plugs in 1969, and five in 1970.

As well as reflecting nicely on Ossa’s carburetion, piston porting, and combustion chamber design, this sort of adaptability is inherent to a mildly tuned engine and is probably the best argument for the trail rider to choose such a machine over a high output dirt racer of the same brand and displacement.

There is yet another argument favoring the Pioneer over the Stilleto racer—at least for the majority of casual riders. While every dirt rider toys with the idea of acquiring a racing oriented machine (whether the motivation be image, more noise, power, or what have you), he may be surprised to find that if he removes the lighting equipment from the enduro model, he can get around a race course as fast or faster than he can on the motocross model. This is because the flexible power band of the enduro engine allows him to get on the gas sooner coming out of turns than he can with the feistier motocrosser. An enduro engine induces less wheelspin, while making directional control by means of throttle application a less nervewracking proposition.

Improvements to the 1971 Pioneer make it even more tempting in this respect. Take the new five-speed transmission, for instance.

While the Pioneer doesn’t need a five-speed insofar as its engine characteristics are concerned, the rider benefits from the addition of the fifth ratio for two reasons. One, high gear is higher than on the previous gearbox, while low gear remains the same. This allows a better top speed, and makes occasional runs at freeway speeds possible. The four-speed had a top speed of about 69 to 70 mph, but you wouldn’t want to cruise it at 65 mph for any sustained length of time. Two, with five speeds, the intermediate ratios are closer together, allowing much faster, neater shifts. One disadvantage of the old wide-ratio four-speed gearbox was the necessity to wait for a brief instant for the flywheel and gear train to catch up with themselves between gears, particularly between 3rd and 4th. With the gear spacing closer together, the process is almost instantaneous, and much more akin to that of the close-ratio racing model. A shortened foot lever on the new Pioneer also helps to make gearchanging easier and faster, as it is no longer necessary to move the left foot uncomfortably forward to reach the lever.

Another important improvement is the adoption of Betor telescopic forks and five-way adjustable rear shock absorbers. The resulting ride is softer, with the full travel of front (7-in.) and rear units being utilized. Rebound damping at the front is particularly improved, and the front wheel is more likely to follow the ground when full throttle is applied with the bike leaned over in a bumpy slow turn. Aluminum triple clamps, with double-bolt ties for the stanchions, complement the new forks.

The suspension system seems generally well balanced, particularly for straight-line running over hoop-dee-doos, or choppy loam. On the fireroads, the back end wallows slightly when powersliding through a cushion; the wheelbase and raketrail combination is not conducive to very precise control in slow speed slides. This latter comment is more for description than criticism, as it is impossible to design a good rough terrain machine that also handles like a Class C tracker.

Typical to its breed is the Pioneer’s forte: to be able to blast up a wash at 70 mph, then bolt across a jolting powerline cut without unseating the rider or causing him great discomfort, and finally turn up a bouldered trail which must be negotiated with the precision of a trialer. Fast or slow, rough or tight, versatility is what this machine is all about.

The fiberglass components are now made oí a flexible material that bounces back after impact. You can take your thumb and push in the side of the gasoline tank or bend the front fender, and they snap back in place. This characteristic reduces the chance of holing the fuel tank or snapping off a fender in a crash.

For the enduro rider, the addition of a full-sized speedometer/odometer unit with resettable trip indicator is quite welcome. The instrument, driven off the front wheel, is suspended in a “cat’s cradle’’ of rubber bands to isolate it from jolting and vibration.

There are other small changes which mark the evolution oí the Pioneer in the last few years. It sports a crossbrace handlebar, a fuel tank breather hose routed through the steering head, safety reflectors at front and rear, an ignition lock mounted under the headlight with the horn, tougher headlight mounting hardware, dust covers for the handlebar levers, and the lack of passenger footpegs, which we will miss. The rider’s folding footpegs are of much stronger design, featuring deep notches to provide good footgrip; they are hollowed and thus provide a modicum of self-cleaning when the going gets muddy. Front and rear axle pull-out pins will facilitate wheel changes.

As in previous models, the tail section has a compartment for the storage of a small tool package, extra plugs and even a small oil bottle. One warning about anything you put in there. If it is a plug, or any metallic object with sharp corners, it should be generously wrapped in something soft. A loose plug wrench, or screwdriver, will rattle around and chip a hole through the fiberglass compartment in about 80 miles of jarring enduro riding.

The least favorable part of the Pioneer is its seat design. Although the new seat is somewhat more thickly padded than the previous one, it is still not broad enough, nor shaped well enough, to provide good support to the fanny and thighs. For brief rides, it is adequate, but under the relentless pounding of a five-hour enduro it can cause considerable discomfort.

Another point oí' irritation is the silencing system. Our complaint has nothing to do with its effectiveness, guaranteed by a double muffling system one in the exhaust chamber itself and the other in a spring-mounted chromed silencing can which may be removed, reversed and stowed securely on the machine when not in use. But, as Ossa went to the trouble of making this extra silencing unit, we wonder why they have not yet incorporated into it an approved spark arrester design? Most rangers we have encountered in our adventures with the ’69, which has the same unit, look at it perfunctorily and assume that it is a legal spark arrester. But there will come a day when the luck runs out.

Returning to the silencing aspect of this system, however, we find it superior to that of any over-125-cc two-stroke motorcycle sold in the United States today. It is extremely quiet and pleasant sounding, and, frankly, we can find no difference in performance with the extra unit on or off, other than that trailing, hillclimbing and tight slow speed riding is easier with the unit on. In some cases, depending upon the relative humidity, altitude, barometric pressure, etc., top speed is sometimes improved with the can on. And that’s the way we prefer to ride the Pioneer. It’s quieter, less fatiguing, and delivers smoother throttle response.

In straight-line performance, the Pioneer is the equal of anything of its type and displacement. With the lights pulled off to reduce weight, a series of starting line drag races uphill with a leading 250-cc motocross machine manufactured in Europe produced a toss-up. The motocrosser had more steam, but the tractable Pioneer got more of its power to the ground.

The ultimate compliment to the Pioneer was paid it by a long-time four-stroker friend of ours. First of all, the sound didn’t bother him. Secondly, he figured it torqued its way up inclines almost as good as his single-banger. And thirdly, he admitted that if he ever had to swear off four-strokes, he'd probably end up buying a Pioneer, because it was the closest thing to a four-stroke he had ever seen.

A drastic statement, that last one.

OSSA

PIONEER 250

SPECIFICATIONS

$940

PER FORMANCE