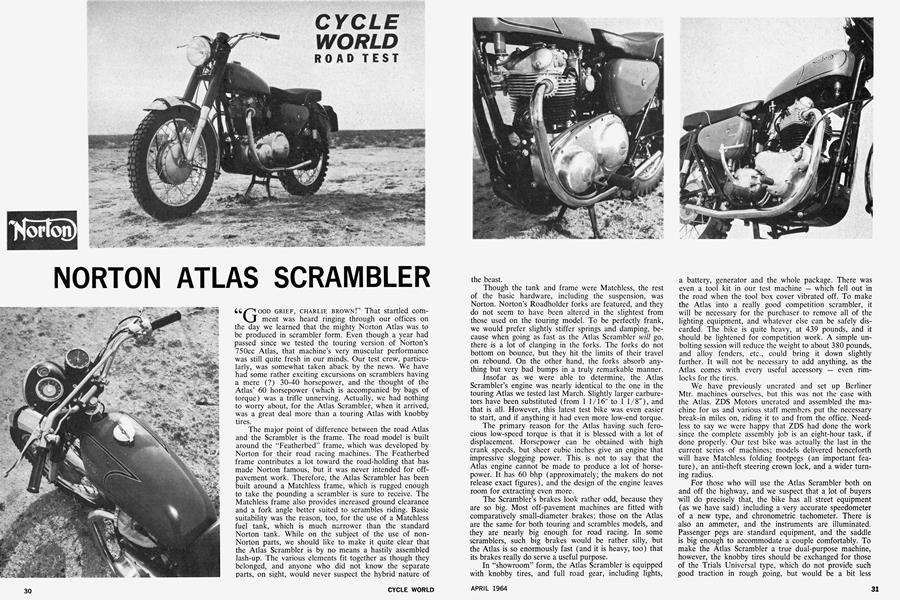

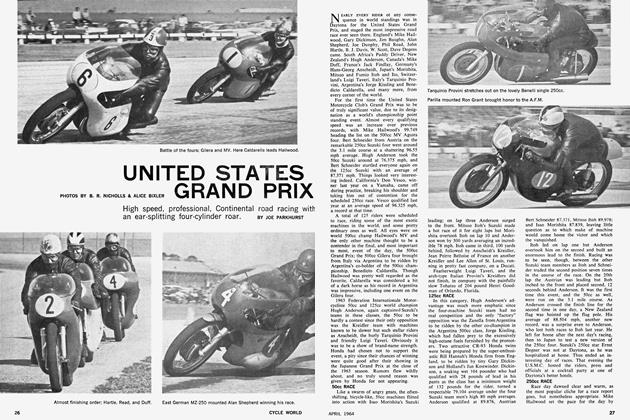

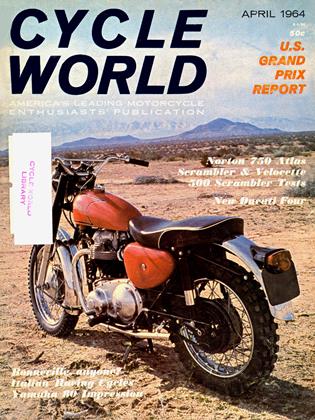

NORTON ATLAS SCRAMBLER

CYCLE WORLD ROAD TEST

"GOOD GRIEF, CHARLIE BROWN!" That startled comment was heard ringing through our offices on the day we learned that the mighty Norton Atlas was to be produced in scrambler form. Even though a year had passed since we tested the touring version of Norton's 750cc Atlas, that machine's very muscular performance was still quite fresh in our minds. Our test crew, particularly, was somewhat taken aback by the news. We have had some rather exciting excursions on scramblers having a mere (?) 30-40 horsepower, and the thought of the Atlas' 60 horsepower (which is accompanied by bags of torque) was a trifle unnerving. Actually, we had nothing to worry about, for the Atlas Scrambler, when it arrived, was a great deal more than a touring Atlas with knobby tires.

The major point of difference between the road Atlas and the Scrambler is the frame. The road model is built around the "Featherbed" frame, which was developed by Norton for their road racing machines. The Featherbed frame contributes a lot toward the road-holding that has made Norton famous, but it was never intended for offpavement work. Therefore, the Atlas Scrambler has been built around a Matchless frame, which is rugged enough to take the pounding a scrambler is sure to receive. The Matchless frame also provides increased ground clearance and a fork angle better suited to scrambles riding. Basic suitability was the reason, too, for the use of a Matchless fuel tank, which is much narrower than the standard Norton tank. While on the subject of the use of nonNorton parts, we should like to make it quite clear that the Atlas Scrambler is by no means a hastily assembled lash-up. The various elements fit together as though they belonged, and anyone who did not know the separate parts, on sight, would never suspect the hybrid nature of the beast.

Though the tank and frame were Matchless, the rest of the basic hardware, including the suspension, was Norton. Norton's Roadholder forks are featured, and they do not seem to have been altered in the slightest from those used on the touring model. To be perfectly frank, we would prefer slightly stiffer springs and damping, because when going as fast as the Atlas Scrambler will go, there is a lot of clanging in the forks. The forks do not bottom on bounce, but they hit the limits of their travel on rebound. On the other hand, the forks absorb anything but very bad bumps in a truly remarkable manner.

Insofar as we were able to determine, the Atlas Scrambler's engine was nearly identical to the one in the touring Atlas we tested last March. Slightly larger carburetors have been substituted (from 1 1/16" to 1 1/8"), and that is all. However, this latest test bike was even easier to start, and if anything it had even more low-end torque.

The primary reason for the Atlas having such ferocious low-speed torque is that it is blessed with a lot of displacement. Horsepower can be obtained with high crank speeds, but sheer cubic inches give an engine that impressive slogging power. This is not to say that the Atlas engine cannot be made to produce a lot of horsepower. It has 60 bhp (approximately; the makers do not release exact figures), and the design of the engine leaves room for extracting even more.

The Scrambler's brakes look rather odd, because they are so big. Most off-pavement machines are fitted with comparatively small-diameter brakes; those on the Atlas are the same for both touring and scrambles models, and they are nearly big enough for road racing. In some scramblers, such big brakes would be rather silly, but the Atlas is so enormously fast (and it is heavy, too) that its brakes really do serve a useful purpose.

In "showroom" form, the Atlas Scrambler is equipped with knobby tires, and full road gear, including lights, a battery, generator and the whole package. There was even a tool kit in our test machine — which fell out in the road when the tool box cover vibrated off. To make the Atlas into a really good competition scrambler, it will be necessary for the purchaser to remove all of the lighting equipment, and whatever else can be safely discarded. The bike is quite heavy, at 439 pounds, and it should be lightened for competition work. A simple unbolting session will reduce the weight to about 380 pounds, and alloy fenders, etc., could bring it down slightly further. It will not be necessary to add anything, as the Atlas comes with every useful accessory — even rimlocks for the tires.

We have previously uncrated and set up Berliner Mtr. machines ourselves, but this was not the case with the Atlas. ZDS Motors uncrated and assembled the machine for us and various staff members put the necessary break-in miles on, riding it to and from the office. Needless to say we were happy that ZDS had done the work since the complete assembly job is an eight-hour task, if done properly. Our test bike was actually the last in the current series of machines; models delivered henceforth will have Matchless folding footpegs (an important feature), an anti-theft steering crown lock, and a wider turning radius.

For those who will use the Atlas Scrambler both on and off the highway, and we suspect that a lot of buyers will do precisely that, the bike has all street equipment (as we have said) including a very accurate speedometer of a new type, and chronometric tachometer. There is also an ammeter, and the instruments are illuminated. Passenger pegs are standard equipment, and the saddle is big enough to accommodate a couple comfortably. To make the Atlas Scrambler a true dual-purpose machine, however, the knobby tires should be exchanged for those of the Trials Universal type, which do not provide such good traction in rough going, but would be a bit less spooky at high speeds out on the pavement. Also, if the police in your area are the least bit sticky about noise, a pair of mufflers would have to be fitted as none are furnished.

Controls and seating positioning were good, except for the bars; several staff members on the smallish side felt they were a bit too high and narrow. Good ball-end control levers are provided, and no-slip bar grips and foot peg covers. Dual fuel taps on the tank give a "reserve" supply—and that is a point too often neglected on scramblers. The only part of the controls layout we really did not like was the location of the killbutton. This essential item (the Norton has magneto ignition) was clipped to the right handlebar next to the fork crown. Somehow, it would have seemed better if the button had been within thumb's reach from the grip.

All of us were slightly concerned about the effects of 60 or more horsepower on handling; we need not have been. The power proved to be an asset, not an embarrassment, as there are times when a good blast of power is the best means of keeping a situation in hand — and on the Atlas, the power is always there. For most crosscountry running, we were able to simply poke the Atlas into 2nd gear and use all that torque as a sort of automatic transmission. The engine is strong and happy from 15 to 60 mph, and it should be extremely reliable: few riders will be able to hold wide-open throttle long enough to hurt the engine's innards. You twist up the wick hard for a few seconds, shift twice, and you will be lashing along across the boondocks like the rocket for which this motorcycle was so aptly named.

If the engine had been fussy, so much power would have created problems. A sudden blast of that magnitude could put the bike down terribly fast. Fortunately, the big Norton engine comes on in a smooth surge as one cranks the throttle around. In fact, it is not only possible,

but quite natural, for the rider to use the throttle to steer the machine. Just tilt the tank a bit with your knees, and tweak the throttle; the rear wheel will swing around and steer the machine off in the desired direction. This may sound tricky; actually it is a simple technique to master —

if you have a lot of torque on tap.

Despite the difference in gearing (same transmission ratios, but 4.92:1 instead of 4.53:1 overall), the Scrambler has acceleration nearly identical to the touring Atlas, and that means it has slightly better acceleration than almost anything. We ran it at the Lions Club drag strip (Long Beach, Calif.), as is our custom, in standard Scrambler trim except for the rear tire. This was changed to a road tire because the standard knobby simply would not get a bite on pavement. And, in point of fact, the bike developed a fair amount of wheelspin with a 4.00-18 street tire. It was as impressive at the drag strip as it had been out on the desert.

NORTON ATLAS SCRAMBLER

SPECIFICATIONS

$1244.00

PERFORMANCE

View Full Issue

View Full Issue