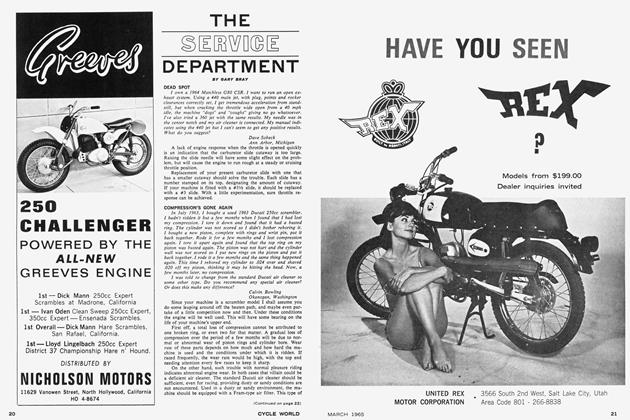

JAMES COTSWOLD 250

CYCLE WORLD ROAD TEST

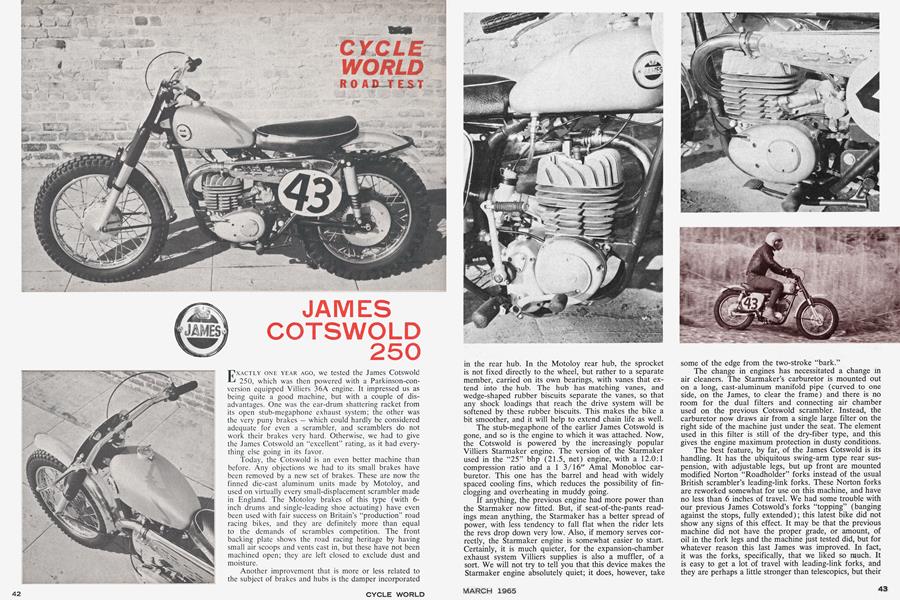

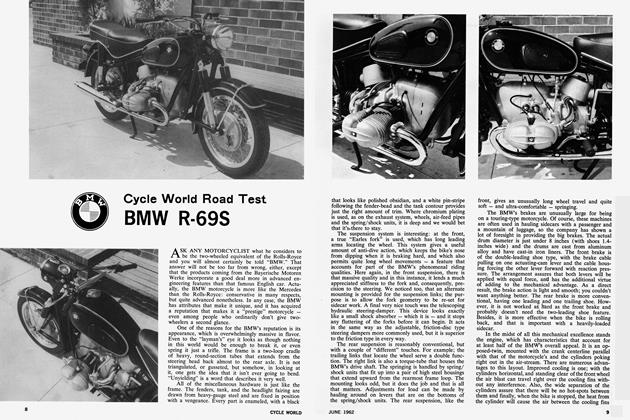

EXACTLY ONE YEAR AGO, we tested the James Cotswold 250, which was then powered with a Parkinson-conversion equipped Villiers 36A engine. It impressed us as being quite a good machine, but with a couple of disadvantages. One was the ear-drum shattering racket from its open stub-megaphone exhaust system; the other was the very puny brakes - which could hardly be considered adequate for even a scrambler, and scramblers do not work their brakes very hard. Otherwise, we had to give the James Cotswold an "excellent" rating, as it had everything else going in its favor.

Today, the Cotswold is an even better machine than before. Any objections we had to its small brakes have been removed by a new set of brakes. These are now the finned die-cast aluminum units made by Motoloy, and used on virtually every small-displacement scrambler made in England. The Motoloy brakes of this type (with 6inch drums and single-leading shoe actuating) have even been used with fair success on Britain's "production" road racing bikes, and they are definitely more than equal to the demands of scrambles competition. The front backing plate shows the road racing heritage by having small air scoops and vents cast in, but these have not been machined open; they are left closed to exclude dust and moisture.

Another improvement that is more or less related to the subject of brakes and hubs is the damper incorporated in the rear hub. In the Motoloy rear hub, the sprocket is not fixed directly to the wheel, but rather to a separate member, carried on its own bearings, with vanes that extend into the hub. The hub has matching vanes, and wedge-shaped rubber biscuits separate the vanes, so that any shock loadings that reach the drive system will be softened by these rubber biscuits. This makes the bike a bit smoother, and it will help to extend chain life as well.

The stub-megaphone of the earlier James Cotswold is gone, and so is the engine to which it was attached. Now, the Cotswold is powered by the increasingly popular Villiers Starmaker engine. The version of the Starmaker used in the "25" bhp (21.5, net) engine, with a 12.0:1 compression ratio and a 1 3/16" Amal Monobloc carburetor. This one has the barrel and head with widely spaced cooling fins, which reduces the possibility of finclogging and overheating in muddy going.

If anything, the previous engine had more power than the Starmaker now fitted. But, if seat-of-the-pants readings mean anything, the Starmaker has a better spread of power, with less tendency to fall flat when the rider lets the revs drop down very low. Also, if memory serves correctly, the Starmaker engine is somewhat easier to start. Certainly, it is much quieter, for the expansion-chamber exhaust system Villiers supplies is also a muffler, of a sort. We will not try to tell you that this device makes the Starmaker engine absolutely quiet; it does, however, take some of the edge from the two-stroke "bark."

The change in engines has necessitated a change in air cleaners. The Starmaker's carburetor is mounted out on a long, cast-aluminum manifold pipe (curved to one side, on the James, to clear the frame) and there is no room for the dual filters and connecting air chamber used on the previous Cotswold scrambler. Instead, the carburetor now draws air from a single large filter on the right side of the machine just under the seat. The element used in this filter is still of the dry-fiber type, and this gives the engine maximum protection in dusty conditions.

The best feature, by far, of the James Cotswold is its handling. It has the ubiquitous swing-arm type rear suspension, with adjustable legs, but up front are mounted modified Norton "Roadholder" forks instead of the usual British scrambler's leading-link forks. These Norton forks are reworked somewhat for use on this machine, and have no less than 6 inches of travel. We had some trouble with our previous James Cotswold's forks "topping" (banging against the stops, fully extended); this latest bike did not show any signs of this effect. It may be that the previous machine did not have the proper grade, or amount, of oil in the fork legs and the machine just tested did, but for whatever reason this last James was improved. In fact, it was the forks, specifically, that we liked so much. It is easy to get a lot of travel with leading-link forks, and they are perhaps a little stronger than telescopies, but their overall weight tends to be slightly greater. Also, and more important, link-type forks inevitably carry a lot of weight out some distance from the steering axis, giving them a lot of inertia and producing a heavy feel. The James' telescopies felt marvelously light and did an entirely acceptable job of absorbing jolts.

We should mention that the James' handling is such that it makes an excellent machine for the beginner. There is a combination of lightness and geometry (rake and trail) that makes it easy for the slightly inept rider to maintain control. Seldom will you encounter situations where the front wheel decides, suddenly, to go its own way. In general, the front end will do everything possible to stabilize itself, and that is a good thing to have when you are trying to get accustomed to pounding along vigorously out in the dirt. In this connection, we should mention that the wide power range of the engine is also a help.

Seating position, and the seat itself, is important on a scrambler, and here the James Cotswold scores rather well, too. The bars are wide and flat, typically "English scrambler," and the relationship to the seat and pegs is, in our opinion, just right. The seat looks thin, but it must be pure padding right to the bottom, for it is very comfortable. Of course, being a British-built scrambler, the Cotswold has its seat and pegs located well to the rear — making it easier for the rider to pull the front wheel up so the machine is in proper "boulder-climbing" position.

Apart from the use of aluminum-alloy fenders, the Cotswold's makers have not gone to any great trouble to build a light machine. The Villiers engine and transmission are reasonably light, having main castings entirely of aluminum, but such items as the fuel tank are of steel. The frame incorporates in its structure several very substantial cast-iron lugs and while these are commonly used on mass-produced road machines it is unusual to see them on a scrambler, where lightness is so important. It is a lot of little things, like this, that account for the Cotswold's all-up weight (with a half-tank of fuel) of 261 pounds. The previous model was lighter, at 40 pounds, but James have added real brakes and a more complicated exhaust system and that is very likely the source of the added weight.

Still, weight or no weight, we very much liked the James. The frame, while admittedly a little heavy, does loop under the engine and protect it from chance encounters with rocks, and it is rigid enough to give good handling — with a little help from the excellent suspension system, of course. We also liked the use of "aircraft" style lock nuts, which is really the only way of insuring against the sudden loss of parts. The bike is a bit nose-heavy, something we noted in our previous test report, but this time around we discovered that the footpeg/handlebar relationship allows the rider to pull the front end into the air anytime he likes. Also, as before, the relatively heavy frame does dampen engine vibrations, and the James feels very smooth as a result. And then there is the finish, which is truly exceptional, and which makes the bike look a bit more handsome than the average small displacement scrambler — which, as a breed, unfortunately tend to resemble argicultural implements. •

JAMES COTSWOLD

SCRAMBLER

$895