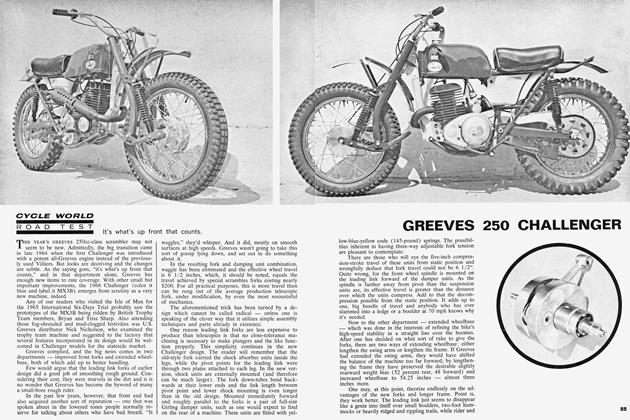

JAWA 250 MOTO-CROSS

CYCLE WORLD ROAD TEST

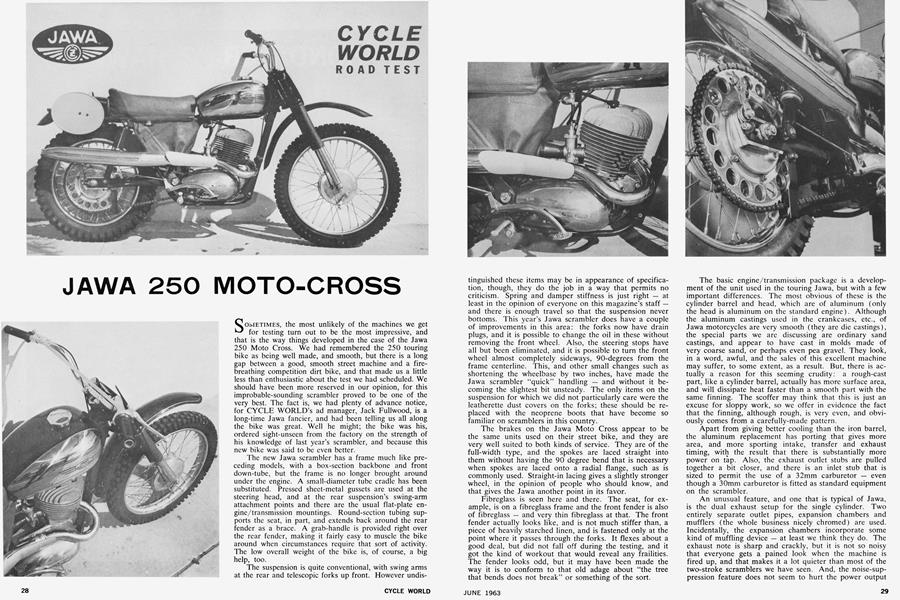

SOMETIMES, the most unlikely of the machines we get for testing turn out to be the most impressive, and that is the way things developed in the case of the Jawa 250 Moto Cross. We had remembered the 250 touring bike as being well made, and smooth, but there is a long gap between a good, smooth street machine and a fire-breathing competition dirt bike, and that made us a little less than enthusiastic about the test we had scheduled. We should have been more reserved in our opinion, for this improbable-sounding scrambler proved to be one of the very best. The fact is, we had plenty of advance notice, for CYCLE WORLD’S ad manager, Jack Fullwood, is a long-time Jawa fancier, and had been telling us all along the bike was great. Well he might; the bike was his, ordered sight-unseen from the factory on the strength of his knowledge of last year’s scrambler, and because this new bike was said to be even better.

The new Jawa scrambler has a frame much like preceding models, with a box-section backbone and front down-tube, but the frame is no longer brought around under the engine. A small-diameter tube cradle has been substituted. Pressed sheet-metal gussets are used at the steering head, and at the rear suspension’s swing-arm attachment points and there are the usual flat-plate engine/transmission mountings. Round-section tubing supports the seat, in part, and extends back around the rear fender as a brace. A grab-handle is provided right over the rear fender, making it fairly easy to muscle the bike around when circumstances require that sort of activity. The low overall weight of the bike is, of course, a big help, too.

The suspension is quite conventional, with swing arms at the rear and telescopic forks up front. However undistinguished these items may be in appearance of specification, though, they do the job in a way that permits no criticism. Spring and damper stiffness is just right — at least in the opinion of everyone on this magazine’s staff — and there is enough travel so that the suspension never bottoms. This year’s Jawa scrambler does have a couple of improvements in this area: the forks now have drain plugs, and it is possible to change the oil in these without removing the front wheel. Also, the steering stops have all but been eliminated, and it is possible to turn the front wheel almost completely sideways, 90-degrees from the frame centerline. This, and other small changes such as shortening the wheelbase by two inches, have made the Jawa scrambler “quick” handling — and without it becoming the slightest bit unsteady. The only items on the suspension for which we did not particularly care were the leatherette dust covers on the forks; these should be replaced with the neoprene boots that have become so familiar on scramblers in this country.

The brakes on the Jawa Moto Cross appear to be the same units used on their street bike, and they are very well suited to both kinds of service. They are of the full-width type, and the spokes are laced straight into them without having the 90 degree bend that is necessary when spokes are laced onto a radial flange, such as is commonly used. Straight-in lacing gives a slightly stronger wheel, in the opinion of people who should know, and that gives the Jawa another point in its favor.

Fibreglass is seen here and there. The seat, for example, is on a fibreglass frame and the front fender is also of fibreglass — and very thin fibreglass at that. The front fender actually looks like, and is not much stiffer than, a piece of heavily starched linen, and is fastened only at the point where it passes through the forks. It flexes about a good deal, but did not fall off during the testing, and it got the kind of workout that would reveal any frailities. The fender looks odd, but it may have been made the way it is to conform to that old adage about “the tree that bends does not break” or something of the sort.

The basic engine/transmission package is a development of the unit used in the touring Jawa, but with a few important differences. The most obvious of these is the cylinder barrel and head, which are of aluminum (only the head is aluminum on the standard engine). Although the aluminum castings used in the crankcases, etc., of Jawa motorcycles are very smooth (they are die castings), the special parts we are discussing are ordinary sand castings, and appear to have cast in molds made of very coarse sand, or perhaps even pea gravel. They look, in a word, awful, and the sales of this excellent machine may suffer, to some extent, as a result. But, there is actually a reason for this seeming crudity: a rough-cast

part, like a cylinder barrel, actually has more surface area, and will dissipate heat faster than a smooth part with the same finning. The scoffer may think that this is just an excuse for sloppy work, so we offer in evidence the fact that the finning, although rough, is very even, and obviously comes from a carefully-made pattern.

Apart from giving better cooling than the iron barrel, the aluminum replacement has porting that gives more area, and more sporting intake, transfer and exhaust timing, with the result that there is substantially more power on tap. Also, the exhaust outlet stubs are pulled together a bit closer, and there is an inlet stub that is sized to permit the use of a 32mm carburetor — even though a 30mm carburetor is fitted as standard equipment on the scrambler.

An unusual feature, and one that is typical of Jawa, is the dual exhaust setup for the single cylinder. Two entirely separate outlet pipes, expansion chambers and mufflers (the whole business nicely chromed) are used. Incidentally, the expansion chambers incorporate some kind of muffling device — at least we think they do. The exhaust note is sharp and crackly, but it is not so noisy that everyone gets a pained look when the machine is fired up, and that makes it a lot quieter than most of the two-stroke scramblers we have seen. And, the noise-suppression feature does not seem to hurt the power output at all; the Jawa scrambler will thunder along with the best of them .

Another improvement over last year's scrambler is the air-filtration system, which consists of a pair of Framtype air cleaner elements. These are enclosed in a leatherette shroud which is lighter than the sheet-metal pressing used previously. The earlier air cleaners used on Jawa scramblers would filter out boulders, but were something less than perfect in the dust-laden air at the average American scrambles event.

The electrics on this new scrambler have also been considerably rearranged. A single 6-volt wet-cell battery is used, in place of a pair of dry-cell batteries. The battery is tucked away under the seat, near the air cleaners, and there is a pair of ignition coils, one for each of the spark plugs (the engine has dual ignition). A 3-position switch operates the ignition: “down” switches on the battery; the middle position is “off”; and when the switch is pulled “up,” the ignition current is drawn from a crankshaft-mounted dynamo. This last is an emergency position, and the engine is rather reluctant to kick-start on the dynamo, although it can be pushstarted easily and will run perfectly with the switch in that position.

The dynamo cover has been cut away to give easy access to the clutch adjustment mechanism, a measure that was being employed by most of the riders anyway. The clutch is, by the way, still connected to the shift lever through an operating cam, and the clutch lever need not be touched except to get underway. After that, the rider can stomp and yank at the lever all he likes without having to touch the clutch lever. We liked this feature a great deal, and found ourselves changing gears while airborne, and in the middle of corners, because it could be done so easily and did not require us to loosen our panic-stricken grip on the bars.

Speaking of the handlebars; the ones that are supplied on the Jawa scrambler are dandies. They look peculiar, and when the machine was uncratcd and assembled, the owner remarked that they “would have to go.” Experience, that most effective of all convincers, soon showed us that this was not going to be necessary. Those bars proved to be one of the bike’s best features, and now its owner would not part with them for the world and all that’s in it. Strangely enough, they suited everyone on our staff perfectly, and our staff ranges in size and reach fairly considerably. We were also pleased to note that the control levers had ball-ends.

Standard gearing on the Jawa Moto Cross is with a 14tooth countershaft and 62-tooth rear wheel sprocket, which limits the top speed to not much more than 60 mph — which is fine for Continental FIM events, as these cannot, by regulation, exceed a 30 mph average speed. With the bike, the purchaser also gets a kit that contains, among other things, a 65-tooth rear sprocket, and 13and 15-tooth countershaft sprockets. This provides quite a variety of gearing.

The “goodie” kit also contains a spare piston and rings, a set of 5 clutch plates, a chain master link, a spare foot peg, an extra spark plug and a small tool-roll. The spare piston is, we think, just a couple of thousandths oversize, so that the bore can be honed clean and the bike raced again without getting into a rebore job.

No racing two-stroke is ever easy to start, but the Jawa provided us with a minimum of aggravation. The kick lever is a bit short, and it is necessary to snap it through its stroke with the toe; if the engine is not flooded it will usually start immediately.

After the first staff member took the first ride on Jawa’s new scrambler, there was a big struggle to see who would be next, and everyone was ready for seconds long before whomever happened to be riding was willing to quit. This created quite a problem, as anyone on the machine did not want to surrender it, and we didn’t have anything that would catch the Jawa. Thus, each time a new rider would take over, the bike would disappear in the distance, trailing a rooster-tail of sand, and would not be seen again for what seemed like hours. Each rider found, in turn, that the Jawa’s handling was almost too much to be believed. Even our less-skilled dirt riders (and we have a couple) were jumping the bike like a gazelle and in general behaving themselves just as though they knew what they were doing — which was an illusion, as they well knew. Our experts, too, were delighted with the machine, and this is one scrambler we would recommend for expert, or novice, and it would make a pretty good puttering-around bike for the man who likes to go cow-trailing and has no inclination toward outright racing. We would like the machine a bit better if the overall finish were not so crude, but we are inclined to overlook anything else in our enthusiasm for its performance. •

JAWA 250 SCRAMBLER

$740.00,