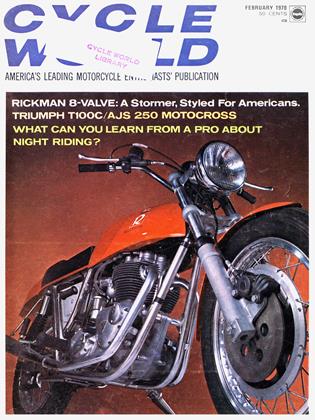

AJS Y4 MOTOCROSS

CYCLE WORLD ROAD TEST

The Y4 is a New Dirt Racer Built to Revive an Old Name. It is Definitely British in Conception. And It Has What It Takes.

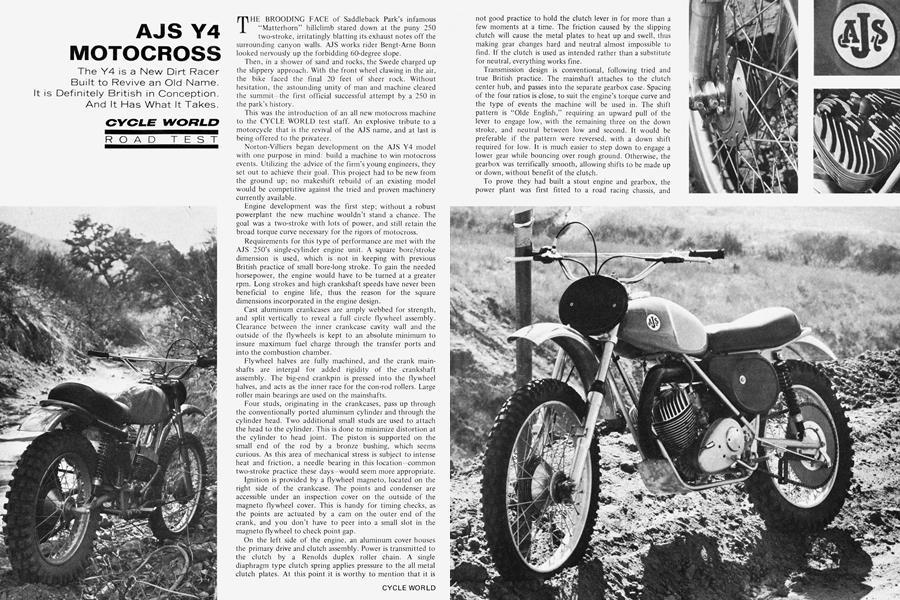

THE BROODING FACE of Saddleback Park's infamous "Matterhorn" hillclimb stared down at the puny 250 two-stroke, irritatingly blatting its exhaust notes off the surrounding canyon walls. AJS works rider Bengt-Arne Bonn looked nervously up the forbidding 60-degree slope.

Then, in a shower of sand and rocks, the Swede charged up the slippery approach. With the front wheel clawing in the air, the bike faced the final 20 feet of sheer rock. Without hesitation, the astounding unity of man and machine cleared the summit—the first official successful attempt by a 250 in the park’s history.

This was the introduction of an all new motocross machine to the CYCLE WORLD test staff. An explosive tribute to a motorcycle that is the revival of the AJS name, and at last is being offered to the privateer.

Norton-Villiers began development on the AJS Y4 model with one purpose in mind: build a machine to win motocross events. Utilizing the advice of the firm’s young engineers, they set out to achieve their goal. This project had to be new from the ground up; no makeshift rebuild of an existing model would be competitive against the tried and proven machinery currently available.

Engine development was the first step; without a robust powerplant the new machine wouldn’t stand a chance. The goal was a two-stroke with lots of power, and still retain the broad torque curve necessary for the rigors of motocross.

Requirements for this type of performance are met with the AJS 250’s single-cylinder engine unit. A square bore/stroke dimension is used, which is not in keeping with previous British practice of small bore-long stroke. To gain the needed horsepower, the engine would have to be turned at a greater rpm. Long strokes and high crankshaft speeds have never been beneficial to engine life, thus the reason for the square dimensions incorporated in the engine design.

Cast aluminum crankcases are amply webbed for strength, and split vertically to reveal a full circle flywheel assembly. Clearance between the inner crankcase cavity wall and the outside of the flywheels is kept to an absolute minimum to insure maximum fuel charge through the transfer ports and into the combustion chamber.

Flywheel halves are fully machined, and the crank mainshafts are intergal for added rigidity of the crankshaft assembly. The big-end crankpin is pressed into the flywheel halves, and acts as the inner race for the con-rod rollers. Large roller main bearings are used on the mainshafts.

Four studs, originating in the crankcases, pass up through the conventionally ported aluminum cylinder and through the cylinder head. Two additional small studs are used to attach the head to the cylinder. This is done to minimize distortion at the cylinder to head joint. The piston is supported on the small end of the rod by a bronze bushing, which seems curious. As this area of mechanical stress is subject to intense heat and friction, a needle bearing in this location—common two-stroke practice these days—would seem more appropriate.

Ignition is provided by a flywheel magneto, located on the right side of the crankcase. The points and condenser are accessible under an inspection cover on the outside of the magneto flywheel cover. This is handy for timing checks, as the points are actuated by a cam on the outer end of the crank, and you don’t have to peer into a small slot in the magneto flywheel to check point gap.

On the left side of the engine, an aluminum cover houses the primary drive and clutch assembly. Power is transmitted to the clutch by a Renolds duplex roller chain. A single diaphragm type clutch spring applies pressure to the all metal clutch plates. At this point it is worthy to mention that it is not good practice to hold the clutch lever in for more than a few moments at a time. The friction caused by the slipping clutch will cause the metal plates to heat up and swell, thus making gear changes hard and neutral almost impossible to find. If the clutch is used as intended rather than a substitute for neutral, everything works fine.

Transmission design is conventional, following tried and true British practice. The mainshaft attaches to the clutch center hub, and passes into the separate gearbox case. Spacing of the four ratios is close, to suit the engine’s torque curve and the type of events the machine will be used in. The shift pattern is “Olde English,” requiring an upward pull of the lever to engage low, with the remaining three on the down stroke, and neutral between low and second. It would be preferable if the pattern were reversed, with a down shift required for low. It is much easier to step down to engage a lower gear while bouncing over rough ground. Otherwise, the gearbox was terrifically smooth, allowing shifts to be made up or down, without benefit of the clutch.

To prove they had built a stout engine and gearbox, the power plant was first fitted to a road racing chassis, and entered in various club and national events throughout England. Different exhaust lengths, port timing, carburetor sizes, and tuning methods were tried until the desired power and reliability had been achieved.

With the advent of the Japanese two-stroke Twin road racing machinery, the fact was evident that AJS would have to campaign their 250 Single in a more viable field of motorcycle competition. What better alternative than motocross?

Frame, forks, and wheels had to be designed with light weight and maximum strength the keynote. The Norton Commando frame met the basic requirements, so a scaled down version was assembled by the Reynolds Metal Tubing Company, using 531 steel alloy, one of the strongest available. A large diameter, thin wall tube makes up the backbone, while smaller duplex tubes cradle the engine-gearbox unit. Diagonal tubes form a triangle to join the main toptube with the duplex cradle members, and provide additional strength between the steering head area and the swinging arm pivot point.

Reynolds 531 is also used for the swinging arm. Flat plates, welded to the duplex tubes that cradle the engine, spread out the stress of the pivot area. Rear chain adjustment is carried out Rickman Metisse style, but with a minor variation. The eccentric discs don’t have to be changed as on the Metisse, only rotated to give the desired slack in the rear chain. This method eliminates adjustment at the rear wheel, and assures a more rigid wheel to swinging arm attachment, while sprocketto-chain alignment is held constant.

Wheels and forks are AJS’s own design, and show thought as well as quality in their construction. Conical alloy hubs riding on sealed ball bearings carry the load, while 5-in. diameter brake drums on both wheels do a good job of stopping. Bigger brakes would be unnecessary weight, and might prove harmful on the slippery surface of a motocross course. Impact resisting steel rims are spoked to the hubs.

The fork stanchion tubes are chromed, and slide freely in aluminum lower legs. Internal springs work evenly throughout 7 in. of travel. Damping is on the stiff side, but does provide a stable feeling over the rough. There is no rebound “klunk” or bottoming out when landing hard. They work well; the stiffness might be cured by more riding time or lighter weight oil.

A color-impregnated orange gas tank gives the Ajay a functional look. It is narrow and gives the rider good knee grip to control the machine. The gas cap is the flip-top variety, and would occasionally pop open at the wrong time, allowing fuel to slosh out. We were assured by Peter Inchley, AJS competition manager, that the cap was being changed to eliminate the problem. The black vinyl cloth covered seat is comfortable and well placed, allowing the rider to shift his weight to and fro for better traction at the rear, or to keep the front wheel from getting too close to the vertical point. Both fenders are aluminum, and do a minimal job of keeping the mud off the rider. The rear is rubber mounted, while the front is attached to a spring steel brace that is bolted to the lower fork yoke. The one-piece exhaust pipe/expansion chamber unit is also rubber mounted, and self-locking nuts are used throughout to attach the various components. Footpegs are aluminum alloy, and are adjustable for height by rotating them on a splined shaft. They also fold, and have a flat steel spring to return them to their original position should a stray immovable object be encountered. The controls all work nicely, although the aluminum clutch and hand brake levers are stiff and thus prone to break easily.

When AJS had a complete machine, British motocross star Malcolm Davis was selected to give the new model a go. He satisfied the firm by taking the British 250 Motocross Championship in 1968, the Y4’s first season of competition.

The new Ajay two-stroke has all the necessary ingredients to make it a successful motocross machine. The engine is functional and performs well. Starting was never a problem. Even when it was loaded up by using the wrong gear and too much throttle, two or three kicks would bring it back to life. The power curve is mild and there is never a feeling that a sudden burst will make the machine unmanageable. The Y4 does possess a creditable amount of torque for a 250. It is very easy to overrun the engine’s torque peak without knowing it. This just wastes the usefulness of its pulling power, and prematurely wears the internals out. Best results are gained in performance by shifting to a higher gear early, and letting the engine pull. This riding technique gives more traction and makes handling easier.

Suspension, front and rear, is one of the Finer points of the machine. The forks allow the rider to maintain control without the fear of the bars being pulled from his hands. Bumps and ruts are navigated with minimum effort, and suspension movement during both compression and rebound is smooth and consistent.

The rear dampers allow just a hair more travel than apparently was foreseen in the placement of the rear frame loop, for the rear wheel rubs the fender slightly when landing hard. A logical remedy here would be to bend the rear frame loop upward slightly, allowing a higher position for the fender. At any rate, the rubbing effect is hardly perceivable to the rider, and it certainly didn’t prevent Davis from winning that British title!

The Ajay has a feeling of neutrality about it, something like a tree branch that springs back to its original position when bent. When getting out of shape over rocks and jumps, the Y4 would return to the stable condition it held previously. This is not to say one cannot fall off, but the Ajay does try to keep its wheels on the ground, even when the rider is doing his best (or worst) to counteract the machine’s built-in stability. Weight distribution is in keeping with motocross tradition of having a light front end. It is possible to pull the front end up with the throttle, but the machine does not give the feeling that it wants to go over backwards.

Success of the Y4 as a machine designed to win motocross races, of course, has yet to be proven. But the machine seems to have most of the necessary attributes: excellent geometry, predictable and effective suspension, and robust engine/gearbox unit with a generous power band. On a more subjective level, the bike simply feels proper. If that seat-of-the-pants sampling informs us truthfully, the new AJS will do well.

AJS Y4 MOTOCROSS

$1075

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsRound Up

February 1970 By Joe Parkhurst -

Letters

LettersLetters

February 1970 -

Departments

DepartmentsThe Scene

February 1970 -

Features

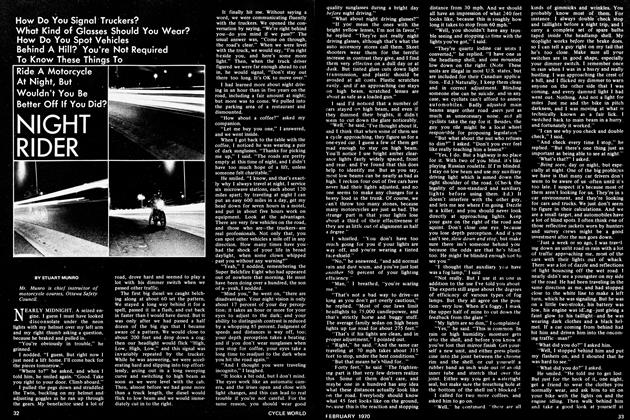

FeaturesNight Rider

February 1970 By Stuart Munro -

Features

FeaturesHow To Teach Your Girl To Ride

February 1970 By David C. Hon -

Special Color Feature

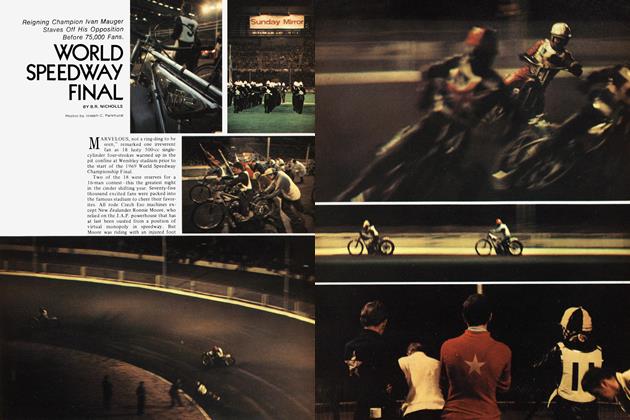

Special Color FeatureWorld Speedway Final

February 1970 By B.R. Nicholls