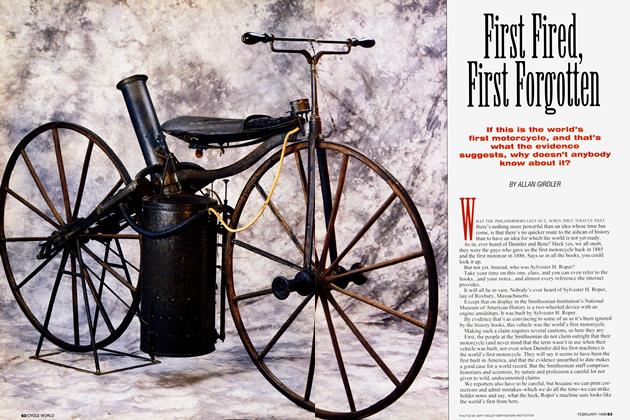

IF EVER A WIZARD THERE WAS

Chronic Timekeeper. Perfectionist. That Is Francis Beart, One Of England's Best Privateer Tuners.

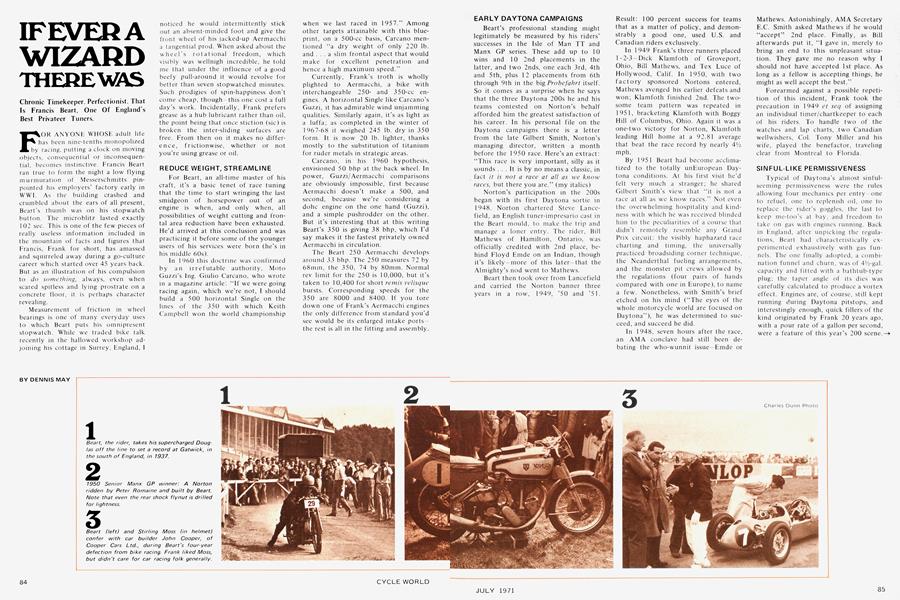

DENNIS MAY

FOR ANYONE WHOSE adult life has been nine-tenths monopolized by racing, putting a clock on moving objects, consequential or inconsequential, becomes instinctive. Francis Beart ran true to form the night a low flying murmuration of Messerschmitts pinpointed his employers’ factory early in WWI. As the building crashed and crumbled about the ears of all present, Beart's thumb was on his stopwatch button. The microblitz lasted exactly 102 sec. This is one of the few pieces of really useless information included in the mountain of facts and figures that Francis, Frank for short, has amassed and squirreled away during a go-culture career which started over 45 years back. But as an illustration of his compulsion to do something, always, even when scared spit less and lying prostrate on a concrete floor, it is perhaps character revealing.

Measurement of friction in wheel bearings is one of many everyday uses to which Beart puts his omnipresent stopwatch. While we traded bike talk recently in the hallowed workshop adjoining his cottage in Surrey, England, 1 noticed he would intermittently stick out an absent-minded foot and give the front wheel of his jacked-up Aermacchi a tangential prod. When asked about the wheel’s rotational freedom, which visibly was wellnigh incredible, he told me that under the influence of a good beefy pull-around it would revolve for better than seven stopwatched minutes. Such prodigies of spin-happiness don't come cheap, though this one cost a full day’s work. Incidentally, Frank prefers grease as a hub lubricant rather than oil, the point being that once stiction (sic) is broken the inter-sliding surfaces are free. From then on it makes no difference, frictionwise, whether or not you're using grease or oil.

REDUCE WEIGHT, STREAMLINE

For Beart, an all-time master of his craft, it’s a basic tenet of race tuning that the time to start wringing the last smidgeon of horsepower out of an engine is when, and only when, all possibilities of weight cutting and frontal area reduction have been exhausted. He’d arrived at this conclusion and was practicing it before some of the younger users of his services were born (he's in his middle 60s).

In I960 this doctrine was confirmed by an irrefutable authority, Moto Guzzi’s lng. Giulio Carcano, who wrote in a magazine article: “If we were going racing again, which we’re not, I should build a 500 horizontal Single on the lines of the 3 50 with which Keith Campbell won the world championship when we last raced in 1957.” Among other targets attainable with this blueprint, on a 500-cc basis, Carcano mentioned “a dry weight of only 220 lb. and ... a slim frontal aspect that would make for excellent penetration and hence a high maximum speed.”

Currently, Frank's troth is wholly plighted to Aermacchi, a bike with interchangeable 250and 350-cc engines. A horizontal Single like Carcano’s Guzzi, it has admirable wind unjamming qualities. Similarly again, it's as light as a luffa; as completed in the winter of 1967-68 it weighed 245 lb. dry in 350 form. It is now 20 lb. lighter, thanks mostly to the substitution of titanium for ruder metals in strategic areas.

Carcano, in his I960 hypothesis, envisioned 50 blip at the back wheel. In power, Guzzi/Aermacchi comparisons are obviously impossible, first because Aermacchi doesn’t make a 500, and second, because we’re considering a dohc engine on the one hand (Guzzi), and a simple pushrodder on the other. But it’s interesting that at this writing Beart's 350 is giving 38 blip, which I’d say makes it the fastest privately owned Aermacchi in circulation.

The Beart 250 Aermacchi develops around 33 blip. The 250 measures 72 by 68mm, the 350, 74 by 80mm. Normal rev limit for the 250 is 10,000, but it’s taken to 10,400 for short remis velisque bursts. Corresponding speeds for the 350 are 8000 and 8400. If you tore down one of Frank’s Aermacchi engines the only difference from standard you'd see would be its enlarged intake portsthe rest is all in the fitting and assembly.

EARLY DAYTONA CAMPAIGNS

Beart’s professional standing might legitimately be measured by his riders’ successes in the Isle of Man TT and Manx GP series. These add up to 10 wins and 10 2nd placements in the latter, and two 2nds, one each 3rd, 4th and 5th, plus 12 placements from 6th through 9th in the big Probefahrt itself. So it comes as a surprise when he says that the three Daytona 200s he and his teams contested on Norton’s behalf afforded him the greatest satisfaction of his career. In his personal file on the Daytona campaigns there is a letter from the late Gilbert Smith, Norton's managing director, written a month before the 1950 race. Here’s an extract : “This race is very important, silly as it sounds ... It is by no means a classic, in fact it is not a race at all as we know races, but there you are.” (my italics)

Norton’s participation in the 200s began with its first Daytona sortie in 1948. Norton chartered Steve Lancefield, an English tuner-impresario cast in the Beart mould, to make the trip and manage a loner entry. The rider, Bill Mathews of Hamilton, Ontario, was officially credited with 2nd place, behind Floyd Emde on an Indian, though it’s likely —more of this later—that the Almighty’s nod went to Mathews.

Beart then took over from Lancefield and carried the Norton banner three years in a row, 1949, ’50 and ’51. Result: 100 percent success for teams that as a matter of policy, and demonstrably a good one, used U.S. and Canadian riders exclusively.

In 1 949 Frank’s three runners placed 1-2-3 —Dick Klamfoth of Groveport, Ohio, Bill Mathews, and Tex Luce of Hollywood, Calif. In 1950, with two factory sponsored Nortons entered, Mathews avenged his earlier defeats and won; Klamfoth finished 2nd. The twosome team pattern was repeated in 1951, bracketing Klamfoth with Boggy Hill of Columbus, Ohio. Again it was a one-two victory for Norton, Klamfoth leading Hill home at a 92.81 average that beat the race record by nearly 4'A mph.

By 195 1 Bean hail become acclima tized to the totally unhuropean I)av tona conditions. At his first visit he'd felt very much a stranger~ he shared Gilbert Smith's view that "it is not a race at all as we know races.'' Not even tlie overwhelming hos~iita1itv and kind ness with which he was received blinded him to th~..' peculiarities ot a course that didn~t remotely resemble any Grand Prix circuit: the visibly haphazard race charting and timing. the universally practiced broadsiding corner technique, the Neanderthal fueling arrangements, and the monster pit crews allowed by the regulations (tour pairs of hands compared with one in hurope ). to name a few. Nonetheless, with Smith's brief etched on his mind ("The eyes of the whole motorcycle world are focused on Daytona"). he was determined to suc ceed, and succeed he did.

In 1948, seven hours after the race, an AMA conclave had still been debating the who-wunnit issue —Emde or Mathews. Astonishingly, AMA Secretary E.C. Smith asked Mathews if he would “accept” 2nd place. Finally, as Bill afterwards put it, “I gave in, merely to bring an end to this unpleasant situation. They gave me no reason why 1 should not have accepted 1st place. As long as a fellow is accepting things, he might as well accept the best.”

Forearmed against a possible repetition of this incident, Frank took the precaution in 1949 et seq of assigning an individual timer/chartkeeper to each of his riders. To handle two of the watches and lap charts, two Canadian wellwishers, Col. Tony Miller and his wife, played the benefactor, traveling clear from Montreal to Florida.

SINFUL-LIKE PERMISSIVENESS

Typical of Daytona’s almost sinfulseeming permissiveness were the rules allowing four mechanics per entry one to refuel, one to replenish oil, one to replace the rider’s goggles, the last to keep me-too’s at bay, and freedom to take on gas with engines running. Back m England, after unpicking the regulations, Beart had characteristically experimented exhaustively with gas funnels. The one finally adopted, a combination funnel and churn, was of 4'A-gal. capacity and fitted with a bathtub-type plug; the taper angle of its dies was carefully calculated to produce a vortex effect. Engines are, of course, still kept running during Daytona pitstops, and interestingly enough, quick fillers of the kind originated by Frank 20 years ago, with a pour rate of a gallon per second, were a feature of this year’s 200 scene. —

Success never came easy to Beart at Daytona. Setting an ominous precedent, the Nortons broke their frames during 1949 training and were exquisitely repaired by Canadian master welder Frank Carter. Flaying it safe, Beart had Carter come south again in 1950 and '5 1; his services were needed both times. Welding was okay with the organizers, but any form of al fresco strengthening, e.g., gusseting, was out.

Thanks to the generosity of a local well wisher, William T. Thomas, Beart had the free use of a finely equipped workshop each time he visited Daytona. Nevertheless, as dependent as he was on his own two hands for even the most menial machine prepping tasks (apart from any irregular help gratuitously given by the riders), life was certainly no honeymoon. In 1949, when earburetion problems set in, cylinder heads were taken off and put back on again no less than 1 7 times.

A man in Frank's shoes must command at least three unrelated skills; He must be a development engineer cum master mechanic, an organizer of wide ranging capabilities, and invisible but i n d ispensible in situations involving human relationships.

The latter reared their potentially threatening heads the first time he went to Daytona. He'd had an advance tip that one of his riders was a Fhil M’Glass type, overly fond of liquor and late nights. With a directness that doesn't come easily to the notoriously reserved British, Beart, on first making this fun lover's acquaintance, went straight to the point; "Look lay off the booze and get to bed early while we’ve got this job on our hands. When it’s over, and not before, you and 1 will catch up on our drinking together." M’Glass complied without a murmur.

LUCK AND RIDER COOPERATION

In general, Frank says he’s been lucky with his riders, though I suspect it’s "luck" based on their respect for an ex-rider of many attainments in his own right. Frank knows his trade as few others know it. He is a perfectionist in all things, as unsparing with his labor as a Stakhanovite.

Chromie McCandless, the Ulsterman who won the 1949 Junior Manx GF on a Beart Norton and placed 2nd in the same year's Senior, ranked particularly high in Frank’s liking and admiration. Something that Chromie has in common with most U.S. riders of all generations, which is rarer in the U.K. and Ireland, was his deep-rooted love for and knowledge of bikes and unfailing willingness to give his sponsor the benefit of his quiet, unassertive expertise.

As a sidelight on McCandless’s cooperativeness, in the 1950 North-West 200, Beart’s Norton had handled like a supermarket floor trolley. Back at Chromie’s place the same evening. Beart’s eye happened to light on a trials bike, dumped in an inconspicuous corner of the workshop. Appropriate to its purpose in life, it had pronouncedly upright forks, also a small front wheel; 19 in., compared with the Manx Norton's 21 in. "Maybe that’s what we need for racing,” mused Frank, never a man to despise homely empiricism. "So what are we waiting for,” McCandless wanted to know.

The switch to steep forks and a 19-in. front wheel kept them busy until breakfast time the next day, a Sunday. Then, while the Belfast cops obligingly played blind and deaf, Chromie put the unsilenced and otherwise heinously unlawful Manx Norton through prolonged tests on stretches of boulevard in the heart of the city. The improvement in handling and road holding quickly prompted Norton to incorporate the mods in the standard Manx. These were the last structural changes made to the model in the pre-Featherbed frame era.

Norton Rennleiter Joe Craig not only treated himself to the new front end evolved by Frank and Chromie but rounded out the compliment by recruiting the latter to the factory team for the '5 1 IT. Left with a competitive 500 on his hands, Frank offered it to Tommy McEwan for the Senior race. And guess what? McCandless placed 3rd, headed by Geoff Duke, Norton first string, and Doran on one of the works AJS Forcupines. McEwan was 4th. So, short of transporting finishers three and four, fate could hardly have rewarded Beart better.

ANALYSIS OR EDUCATION?

Frank never had a formal engineering education, doesn’t nourish his intellect on heavyweight tomes and isn’t strong on advanced theory. He has picked up what he knows, he says, by forever asking questions and sifting the 5 percent wheat from the 95 percent chaff tlie answers contain, and the painstaking analysis of his failures. All the time I’ve known him, going back to the early Thirties, he’s had the habit of attentively quizzing anyone whose company he’s in, including some who don’t come up to his kneecap in knowledge, experience and intelligence. But just once in a while, he says, the unlikeliest people will let drop an idea, a molecule of information, that’s worth brooding upon and turning to account. He is not intuitive and only had a hunch once in his life. That was on setting out for the Isle of Man at Manx Grand Prix time in 1960. He said to Biddy, his wife, “I'll send you a telegram when we’ve won the Junior race.” Not if, you notice, but when. His rider, Pillis Boyce, not only won but turned the first over-90 Junior race average in the series’ history.

An inveterate logger of logs, Frank has kept detailed records of all the work carried out on every bike and engine owned. He is a man totally absorbed by motorcycle racing. Although educated at one of London’s most famous schools, I'd say he nowadays devotes more time to reading spark plugs than the written word. He and Biddy last took a vacation in 1949, but as his work preoccupied him throughout this ordeal they decided not to repeat it.

Still in good shape physically, and mentally as sharp as a tack, he isn’t thinking of retiring yet. After this year, however, he may relinquish entrant/ sponsor status and just fettle customers’ bikes. This unattached clientele, he estimates, may well have totaled a thousand runners, first to last.

Conditioned to pessimism by failures and setbacks, of which lie’s had his fair share, Beart has a stock maxim: “Never expect anything.” He’s a sensitive fellow, as can be witnessed by his impulsive and immediate quittance of bike racing after two riders, Ivor Arbor and Ken James, were killed during practice for the 195 2 Manx GP on machines he’d prepared. (This wasn’t the first such tragedy: in the late Forties, at intervals separated by a couple of years or so. two other Beart-mounted men met their end on the Island). Frank couldn’t possibly have blamed himself or his mechanic for the 195 2 deaths that prompted his self banishment from the bike scene: Arbor, an unfit man, had blacked out on the approach to a fast curve; James hit cow manure at the same place.

FLIRTATION WITH CARS

Biddy Beart, who’d previously always accompanied Frank to the IOM, vowed she’d never go there again and never did. Frank doubtlessly didn’t intend to but after a flirtation with cars and car racing folk that lasted four seasons, ’53 through ’56, he succumbed to the lure of his first love, bikes. With the exception of Stirling Moss, who during 1954 scored six straight wins, two 2nd places and three lap records on Beart-tuned Cooper-Nortons, all in international races, Frank had little rapport with car people. Moss, a 100-percent professional with a scrupulous code of business ethics, was atypical in his field, and endeared himself to Frank by always knowing his cars as well as, if not better than, the best riders know their bikes. The Cooper that Moss drove, incidentally, was almost as much Beart as Cooper; Frank had bought it CKD, built it up ah initio himself. As you'd expect, it was both lighter and slimmer than standard. Its first time out, it won its race and broke the Goodwood lap record for its class.

It’s sometimes alleged that the services of Frank Beart come expensive, but you can believe him when he says his motorcycle operations haven’t made him a rich man and never could. This perhaps is because only the best of which he is capable satisfies the perfectionist in him, no matter what lie's agreed to accept for a given job. The point is well illustrated by his fanatical bent for weight watching. I recall a Norton of his on which he replaced every original washer with a light alloy one. Just to be sure the substitutes were no thicker or of larger area than they need be, he made them himself, individually. He’s even been known to discard dural spoke nipples and make up Elektron ones instead.

Francis first rode street bikes 49 years ago, while at school learning the rudiments on a make called Duzmo, a corny abbreviation for Does Move. Other roadsters Fallowed and he later acquired and hillclimbed a I I Replica Norton ’27. A 500 Zenith-JAP gave him his combatant introduction to Brooklands track, conveniently located a stone’s throw from his home at Byfleet, Surrey. He entered the employ of the late Fric Fernihough, an established Brooklands star who was to become the world’s fastest rider in the early Thirties. But a wage equivalent to $12 per week, with 9and 1 2-hour days alternating, soon palled, and Frank quit to set up his own Brooklands speedshop in about 1935. (Thirty-five years later, at a reunion of racing oldtimers, the friends of his youth made him a surprise presentation of the doors off his original Brooklands workshop, with his name and ad matter still visible in faded paint.)

(Continued on page 110)

Continued from page 87

A VERSATILE TUNER/ENTRANT

Once seriously launched on a career as a tuner/entrant, his lack of specialized book learning didn’t seem to handicap him at all. In association with such track and road racing notables of the period as Dennis Minnet, Charles Mortimer Sr., Jock Forbes, and Johnny Lockett, earmarked for later and greater fame as a member of the Norton factory team, he was soon putting race winning and world record breaking on a wholesale footing. Nine-tenths of this lateThirties Beart activity was concentrated on Nortons of 350and 500-cc displacement, all of them compressioned for and running on alcohol. Although technically of local significance only, Minnet, who doubled in the throttle twisting and mechanic roles for Francis, cracked a uniquely hard nut the day he lapped Brooklands at over 100 mph from a standing start. He was the only rider ever to do so on a 500.

Beart’s own riding around this time was mostly done in sprints and on the short Mountain Circuit at Brooklands. In the former he rang changes between Nortons and a highly potent Douglas horizontal Twin, sometimes run with supercharger, sometimes not. In fighting a full-lock wobble that this one once developed at Brooklands, Frank took a mauling that still prevents him from straightening his right arm fully.

By the Emerson axiom, “Skill to do comes with doing,” but the converse never held water in Beart.’s case. After specializing all along on alcohol burners, he was asked in 1938 by Dennis Mansell, son of Norton Motors’ then managing director, to build and prep an engine for John Lockett to use in that year’s Senior Manx GP. Obligatory fuel for the Manx was a 50/50 mix of gasoline and benzol. Although totally unfamiliar with this form of fuel, he nevertheless undertook the job, completing it at the eleventh hour, actually on the Island. Skill to do had evidently come with very little doing, for Lockett led the entire field for over half the race, finally placing 2nd behind Ken Bills.

Years later, in 1963, he again demonstrated speed in mastering an unfamiliar technique when Bert Greeves of the Greeves motorcycle firm turned over one of his racing two-strokes to Frank and invited him to get the bugs out. To the marked betterment of power and torque, he dropped the compression from l 2: l to l 0: l. complementing this and othei tuning gambits with a weight reduction from 2I5 to 176 lb. and a rework of the rear suspension geometry. First time out, ridden by Joe Dunphy, the transformed Greeves won its 250 race in an international meeting at Crystal Palace, London. "To make a stroker really run," says Frank, "ignition is critical ... it it's less than perfect you've wasted your time.''

(Continued on page 112)

Continued from page 110

This two-stroke experience later came in useful when Beart and Charles Mortimer Sr. teamed as cofounders and directors of the Beart-Mortimer race riders’ school. Frank was responsible for engine tuning and maintenance. The school used Greeves exclusively.

UNSURPASSED IOM RECORD

Although Beart-tlined engines have powered the winners of countless short circuit events, his heart, as already hinted, has always belonged to the two Isle of Man classics, the 11 itself and the Manx GP. In this sphere, no other private entrant has ever come near to matching Frank's success record. A bald listing of riders who have distinguished themselves on the Island on the green and silver flyers reads like a Who's Who of British racing motorcycledom . . . Lockett. Aitchison, Parkinson, McCandless. Romaine, Mchwan, Crossley. Sheppard. Washer, Boyce, Middleton, Minihan, Darvill. Dunphy. Jenkins. Guthrie, Kelly, Uphill, Heckles, Findlay and others.

The relative standings of the TT and the Manx GP being what they are. Joe Dunphy's two 2nd placements in the I f Senior events both times. 1962 and '65 comfortably outweighed the value of the 10 outright wins scored by Beart runners in the Manx CLP. Both Dunphy IT victories were won on Nortons. Only Hailwood (MV) beat him in the 1965 Senior Tl, and Dunphy finished more than four minutes ahead of the 3rd placeman. Two years later, in the 1967 Senior IT, Malcolm Uphill pushed his Beart Norton around the Island at a lap average of over 100 mph, a rare achievement for a single-cylinder bike.

From 1938 through '67. all Frank's Isle of Man endeavors, with the exception of a short A.IS interlude in the earl.y Sixties, were pinned on Nortons. Ehe AJS in question, a 7R. copped Filis Boyce respectable 8th and 9th place finishes in the Junior TTs of 1961 and ’62, and won the 1963 Junior Manx for Peter Darvill. Noticing the flattering interest that rival AJS handlers were showing in his 7R during Manx (»P practice, Beart, with native cunning, shifted the red line on his bike's tach from 8000 to 8400 rpm.

INTERCHANGEABLE ENGINES

Currently. Frank’s efforts are concentrated solely on the TT and the Manx GP, and he campaigns just one bike, the interchangeable engined Aermacchi. It was on this that Jack Findlay. after temporarily occupying 2nd spot, placed 3rd in the 1 969 Junior TT.

Apart from its performance, which for a pushrodder is really out of this parish, the Aermacehi is easy to work on and very reliable; parts are cheap, too. A piston, for instance, costs half as much as the Norton equivalent. After three seasons, the Beart Aermacchi’s pistons in their two sizes are still original. His Nortons always needed replacement conrods every year, and when he had a lucrative Norton dealership and could afford such prodigalities, he was fitting new pistons after every race of TT duration. On the eve of the 1968 Junior TT he dropped a brand new engine, untouched since its arrival from Italy, into the Aermacehi. In the race, ridden by Jack Findlay, the bike was up in 4th place for awhile and finished 6th after running into carb trouble.

He’s never designed an engine in his life, and, as essentially a development engineer, he doesn’t aspire to. He does have some firmly rooted views on the general configuration for roadracing bikes of the future. Presently, the rider sits tall in the saddle, at a prohibitive cost in terms of frontal area. The answer, he thinks, may lie in the banishment of the steering head as we know it and the substitution of a system ot hub-center steering, which would lend itself to a fully prone rider attitude.

He also has dickered with the idea of monocoque construction, the ideal recipe for strength combined with lightness. Beart tried to interest Norton in the idea some years back, but was unsuccessful. Air brakes, using a principle that Mercedes exploited with success on their sports racing cars in the Fifties, are another daydream ot his. Here again, though, conservatism the riders’ in this case -has brought frustration.

Contemplating the modest monetary returns that his labors have brought him in his native Britain, he thinks perhaps he’d have done better in the U.S., “though it's too late now.’’ Well, is it'.’ Personally, I’d say this puts too low an estimate on the powers of a man who, even if he’ll never see another sixty-fifth birthday, probably isn’t more than a degree or two off TDC as an engineering intellect and race campaigner. [Q]