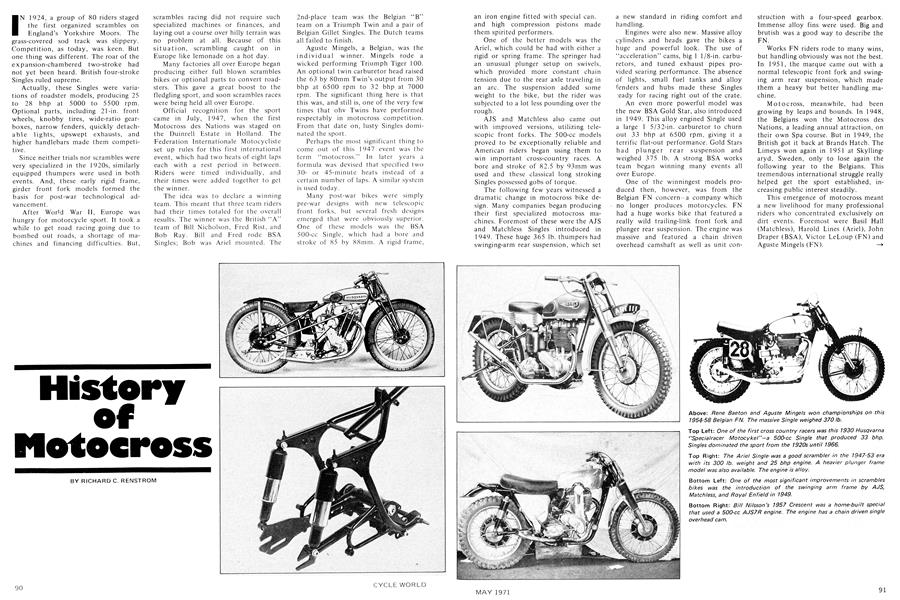

History of Motocross

RICHARD C. RENSTROM

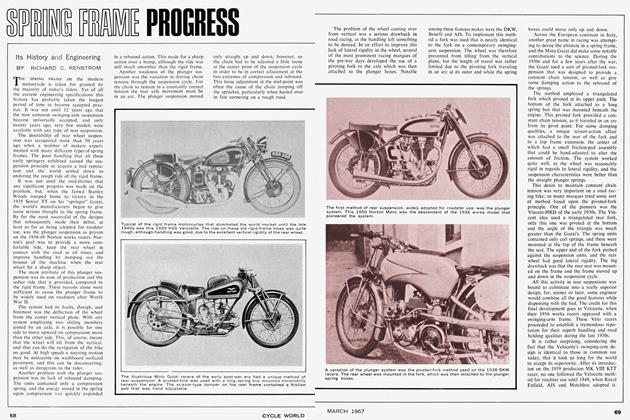

IN 1924, a group of 80 riders staged the first organized scrambles on England's Yorkshire Moors. The grass-covered sod track was slippery. Competition, as today, was keen. But one thing was different. The roar of the expansion-chambered two-stroke had not yet been heard. British four-stroke Singles ruled supreme.

Actually, these Singles were variations of roadster models, producing 25 to 28 bhp at 5000 to 5500 rpm. Optional parts, including 21-in. front wheels, knobby tires, wide-ratio gearboxes, narrow fenders, quickly detachable lights, upswept exhausts, and higher handlebars made them competitive.

Since neither trials nor scrambles were very specialized in the 1920s, similarly equipped thumpers were used in both events. And, these early rigid frame, girder front fork models formed the basis for post-war technological advancement.

After World War 11, Europe was hungry for motorcycle sport. It took a while to get road racing going due to bombed out roads, a shortage of machines and financing difficulties. But,

scrambles racing did not require such specialized machines or finances, and laying out a course over hilly terrain was no problem at all. Because of this situation, scrambling caught on in Europe like lemonade on a hot day.

Many factories all over Europe began producing either full blown scrambles bikes or optional parts to convert roadsters. This gave a great boost to the fledgling sport, and soon scrambles races were being held all over Europe.

Official recognition for the sport came in July, 1947, when the first Motocross des Nations was staged on the Duinrell Estate in Holland. The Federation Internationale Motocycliste set up rules for this first international event, which had two heats of eight laps each with a rest period in between. Riders were timed individually, and their times were added together to get the winner.

The idea was to declare a winning team. This meant that three team riders had their times totaled for the overall results. The winner was the British “A” team of Bill Nicholson, Fred Rist, and Bob Ray. Bill and Fred rode BSA Singles; Bob was Ariel mounted. The

2nd-place team was the Belgian “B” team on a Triumph Twin and a pair of Belgian Gillet Singles. The Dutch teams all failed to finish.

Aguste Mingels, a Belgian, was the individual winner. Mingels rode a wicked performing Triumph Tiger 100. An optional twin carburetor head raised the 63 by 80mm Twin’s output from 30 bhp at 6500 rpm to 3 2 bhp at 7000 rpm. The significant thing here is that this was, and still is, one of the very few times that ohv Twins have performed respectably in motocross competition. From that date on, lusty Singles dominated the sport.

Perhaps the most significant thing to come out of this 1947 event was the term “motocross.” In later years a formula was devised that specified two 30or 45-minute heats instead of a certain number of laps. A similar system is used today.

Many post-war bikes were simply pre-war designs with new telescopic front forks, but several fresh designs emerged that were obviously superior. One of these models was the BSA 500-cc Single, which had a bore and stroke of 85 by 88mm. A rigid frame,

an iron engine fitted with special can. and high compression pistons made them spirited performers.

One of the better models was the Ariel, which could be had with either a rigid or spring frame. The springer had an unusual plunger setup on swivels, which provided more constant chain tension due to the rear axle traveling in an arc. The suspension added some weight to the bike, but the rider was subjected to a lot less pounding over the rough.

AJS and Matchless also came out with improved versions, utilizing telescopic front forks. The 500-cc models proved to be exceptionally reliable and American riders began using them to win important cross-country races. A bore and stroke of 82.5 by 93mm was used and these classical long stroking Singles possessed gobs of torque.

The following few years witnessed a dramatic change in motocross bike design. Many companies began producing their first specialized motocross machines. Foremost of these were the AJS and Matchless Singles introduced in 1949. These huge 365 lb. thumpers had swinging-arm rear suspension, which set

a new standard in riding comfort and ha ndling.

Engines were also new. Massive alloy cylinders and heads gave the bikes a huge and powerful look. The use of “acceleration” cams, big 1 1 /8-in. carburetors, and tuned exhaust pipes provided searing performance. The absence of lights, small fuel tanks and alloy fenders and hubs made these Singles eady for racing right out of the crate.

An even more powerful model was the new BSA Gold Star, also introduced in 1 949. This alloy engined Single used a large 1 5/32-in. carburetor to churn out 33 bhp at 6500 rpm, giving it a terrific flat-out performance. Gold Stars had plunger rear suspension and weighed 375 lb. A strong BSA works team began winning many events all over Europe.

One of the winningest models produced then, however, was from the Belgian FN concern-a company which no longer produces motorcycles. FN had a huge works bike that featured a really wild trailing-link front fork and plunger rear suspension. The engine was massive and featured a chain driven overhead camshaft as well as unit con-

struction with a four-speed gearbox. Immense alloy fins were used. Big and brutish was a good way to describe the FN.

Works FN riders rode to many wins, but handling obviously was not the best. In 1951, the marque came out with a normal telescopic front fork and swinging arm rear suspension, which made them a heavy but better handling machine.

Motocross, meanwhile, had been growing by leaps and bounds. In 1948, the Belgians won the Motocross des Nations, a leading annual attraction, on their own Spa course. But in 1949, the British got it back at Brands Hatch. The Limeys won again in 1951 at Skyllingaryd, Sweden, only to lose again the following year to the Belgians. This tremendous international struggle really helped get the sport established, increasing public interest steadily.

This emergence of motocross meant a new livelihood for many professional riders who concentrated exclusively on dirt events. Foremost were Basil Hall (Matchless), Harold Lines (Ariel), John Draper (BSA), Victor LeLoup (FN) and Aguste Mingels (FN). —>

By 1952, motocross had grown so much that the F1M decided to inaugurate a European Championship. The idea was to stage a series of grand prix events in various countries, which would provide points toward the championship. This championship immediately replaced the Motocross des Nations as the most important criteria of both man and machine, and today it rivals the older road racing sport for popularity and prestige.

The first European Championship proved to be a fantastic battle.

FNs were unbeatable, with John Avery (BSA) following Victor LeLoup and Aguste Mingels. In 1953 Mingels won again, only this time he used a Matchless in several events.

In 1954 the Belgians continued their hold on the trophy, with Mingels trouncing Rene Baeton’s Sarolea Single (also made in Belgium) after a torrid

season. Next came Jeff Smith (BSA) and LeLoup (BSA & FN). These were the great years of motocross, with the giant Mingels handling his huge FN as if it were a toy. These massive machines and po.werfu! men provided a spectacle that really caught the public’s fancy. Crowds over 100,000 began frequenting the major events.

The British, in 1955, finally got it back on the Belgians when John Draper, Bill Nilsson, Sten Lundin and Brian Stonebridge took 1st, 2nd, 4th, and 6th in the championship on BSA Gold Stars. LeLoup finished 3rd on his FN and Les Archer (Norton) got 5th. These 370-lb. Gold Stars were very fast with a 38 blip output at 7000 rpm. Big, powerful sounding, and fast that was motocross in 1 955.

The next year the sport received quite a shock when a privateer on a home-built special trounced all the works bikes something terrible. Les Archer was the man. He used an old 1 94 7 Norton Manx engine with a smaller International head in which Manx valves were installed. The 79 by 100mm single ohc mill used either a 1 3/32or l 5/32-in. TT carburetor. (The larger bore was for fast courses where

peak power is important.) This classic engine was mounted in a home-built swinging arm frame. Dry weight was 350 lb.

Motocross received a big boost 1957 when the FIM elevated it to full world championship status. Bill Nilsson, from Sweden, was the champ that year, and once again it was a home-built special that stove the crowd in.

Bill began with a 350-cc AJS 7R road racing Single. An increase in bore and stroke to 80 by 96mm gave him a cool 483cc. Next came a 1 5/32-in.

carburetor to replace the GP unit. Stock valves were retained. The gearbox came from a BSA Gold Star, and a 7R frame was used with some gussets added extra strength.

For wheels, Bill used the 7R alloy conical hubs with 21-in. front and 19-in. rear steel rims. Next came a BSA fuel tank and Sarolea seat. Nilsson’s idea to get something a little lighter than had previously been used, and his mount was about 30 lb. lighter than the competition.

In 1958, the dashing Rene Baeton took the championship on his ohc Single. Again, the powerful man on big, powerful Single prevailed. After

Rene came Nilsson on his 7R Crescent, Sten Lundin (Monark), John Draper (BSA), Hubert Scaillet (FN), and Jeff Smith (Gold Star).

These bikes were all superb Singles in the 340 to 3 70 lb. range, and all featured long stroking engines with gobs of torque. Reliability was, perhaps, better than today’s fragile lightweights, but it took a muscular man to control one in full flight.

Since motocross had grown at an amazing rate, the F1M decided to add a 250-cc class for 1958 called the Coup d’ Europe. Light 200-lb. two-strokes dominated this class since its inception; little did the world know that here lay the seeds of disaster for the classical Single. It would take time, but the changeover to lightweight machinery was inevitable.

A new era of motocross began when the Swedes started dominating the sport in 1959. The man was Sten Lundin, who used a Monark to edge out Nilsson (Crescent). Next came Dave Curtis (Matchless), Broer Dirks (Gold Star), Les Archer (Norton), Smith (BSA), Don Rickman (Metisse), and Lars Gustafson (Monark). The Monark was produced by a small Swedish concern who used BSA or Husqvarna engines.

The following year Nilsson won again, this time on a Husqvarna that was perhaps the most beautiful motocross machine ever produced. The Husky had a twin-loop cradle frame with Ceriani front forks-the first significant use of this now famous Italian design. Husqvarna borrowed freely from all over Europe, using a 7R rear hub and gearbox.

For a powerplant, an old 1936 pushrod Single was dug out of the warehouse. The stroke was reduced slightly from 101mm to 99, but the stock 79-mm bore was retained. An alloy cylinder and head replaced the cast-iron parts. A high compression piston, Lucas racing magneto, wilder cams, and larger valves were also fitted.

Another concern of Husqvarna’s was weight reduction, and their Single weighed only 312 lb.—a remarkable contrast to the 370-lb. FN or BSA. The engine punched out 35 bhp, which ■ made the bike quite competitive.

In the championship, Nilsson was followed by Lundin (Husqvarna), Rickman (Metisse), Rolf Tibblin (Husqvarna), Gunnar Johannson (Lito), and Ove Lundell (Monark). The following year saw Lundin on top with his Lito, but in

1962 and 1963 Rolf Tibblin trounced the field on his Husky. Swedish bikes took the first five places in the championship in 1962—an awesome display of their superiority. The Lito was a pushrod Single, which had a Ceriani suspension and a weight of around 3 1 0-3 1 5 lb.

During these years the trend had been to lighter models with improved suspension. Power output was actually little greater than the old 1950 Gold Stars, but improved handling was a significant step forward in design evolution. Never again would a heavy Single be competitive. Handling and less weight was the trend.

Meanwhile, BSA had witnessed their proud old Gold Stars being humiliated. Obviously, something had to be done. The Birmingham approach was to enlarge a 250 to 420cc. By using modified 250 frame, it was possible to reduce weight to an unbelievable 255 lb. —50 to 60 lb. less than the Swedish bikes! BSA intentionally sacrificed engine size (and horsepower) to get the job done. Nevertheless. Jeff Smith finished 2nd to Tibblin in 1963.

In 1964, Rolf and Jeff engaged in torrid, season long battle. Smith won

(Continued on page 118)

8th ANNUAL INTERNATIONAL

CYCLE WORLD SHOW

IN CONJUNCTION WITH THE 11TH ANNUAL INTERNATIONAL CUSTOM CAR SHOW AND HOT VW EXTRAVAGANZA / LOS ANGELES MEMORIAL SPORTS ARENA / APRIL 15, 16, 17 & 18,1971 / SEE ALL THE 1971 MODELS FROM EVERY SIGNIFICANT MANUFACTURER IN THE WORLD PLUS HUNDREDS OF DRAG BIKES. CHOPPERS. ANTIQUES, CLASSICS, ROAD RACERS, MOTOCROSSERS, CUSTOMIZED BIKES OF EVERY TYPE, MINI-BIKES, BONNEVILLE STREAMLINERS AND RECORD HOLDERS FROM ALL OVER THE WORLD. THE WORLD’S LARGEST AND MOST INFLUENTIAL MOTORCYCLE SHOW.