Out of the Rubble of World War Ii Came the Nsu Twin of Wilhelm Herz — the First Motorcycle To Break 200

May 1 1968 Richard C. RenstromOut of the Rubble of World War Ii Came the Nsu Twin of Wilhelm Herz — the First Motorcycle To Break 200 RICHARD C. RENSTROM May 1 1968

Ruin to Record

Out of the Rubble of World War II Came the NSU Twin of Wilhelm Herz — The First Motorcycle to Break 200

RICHARD C. RENSTROM

NINETEEN YEARS is a long time to spend in capture of a world speed record, but that is the number of years the German NSU firm spent to become the world's fastest on two wheels at over 200 mph. The NSU record motorcycles were, and remain, among the finest examples of racing engineering excellence that have ever been produced — and a tribute to teutonic patience.

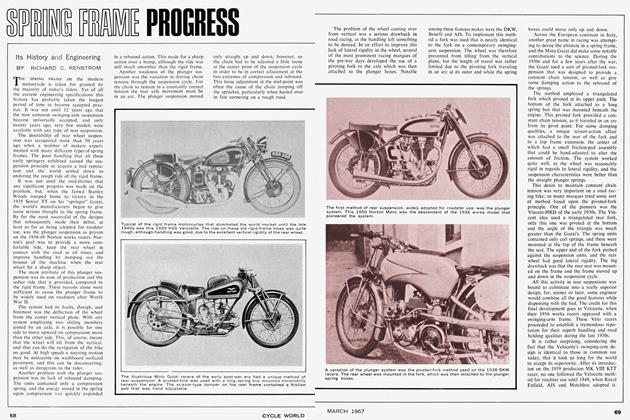

This story of the fabulous NSU speed record bikes started in 1937 when engineer Albert Roder drew up plans for a twincylinder road racing model. International Grand Prix racing had become terribly competitive during the 1930s, with the British singles being overwhelmed late in the period by German and Italian supercharged multi-cylindered machines capable of fantastic performances. Against such a background it was only natural that Herr Roder would think in terms of supercharging, as well as more than one cylinder. Thus his new twin certainly represented the progressive thinking that characterized the racing sport during the 1930-1940 era.

Produced in both 350and 500-cc displacements, the twin featured double overhead camshafts, as well as supercharging from an impeller type unit. The power was fantastic, with 65 and 90 bhp, respectively, from the two engines, which ran on a 50-50 petrol-benzol mixture.

During 1938 and 1939, the German factory raced its supercharged bikes with modest success, but the really major victories always eluded NSU, because the twins were not as roadworthy as was their opposition. Trackside weights were 440 and 486 lb. for the 350 and 500 models. Their high centers of gravity made the twins a handful on tight corners. Other motorcycles gained too much in cornering speed for the NSU to ever regain on the straightaways.

Then came World War II, and the NSU factory was heavily bombed. It was, in fact, not much more than a pile of rubble that greeted Wilhelm Herz in the spring of 1946 when he returned from the war. Herz had been one of NSU’s finest riders in the pre-war days, and he had returned hoping to find the magnificent blown racers intact so that he might once again howl around the classic GP courses.

All that Wilhelm found was the ruins of a once proud company, so he began to dig — by hand. Beneath the bricks and twisted beams of steel he uncovered some parts — an engine that was badly rusted, a bent frame, a pair of wheels, a front fork, and a gearbox. Wilhelm explained his plan to rebuild the illustrious racer to the occupational authorities, and for a purchase price of a few marks they allowed him to take the old warrior to his home shop.

At home began the tedious work of tearing down, then rebuilding a 350-cc model. By the fall of 1947, Wilhelm had completed his project and he gave the bike its first post-war airing. The machine reached a speed of 130 mph. During 1948, Herz won a great number of home country road races on the NSU, and in 1949 he rejoined the company as a works rider because by then the factory had been rebuilt.

One of Wilhelm’s first ideas as a team rider was to approach company executives about his plan to regain some of the lost German prestige by capturing the “world’s fastest” title for motorcycles. Surprisingly, the plan was enthusiastically adopted, but all agreed that it would take several years because Germany still was engaged in rebuilding its war-torn country and financing was not abundant.

So, at the factory, the serious work of building a record machine was undertaken. Herr Roder resumed where he had left off before the war. The 350and 500-cc engines were put on the test bed. Research resulted in development of additional horsepower. A systematic program followed, and, by fitting a vane type blower in place of the original impeller unit, the engineers were able to extract more power.

The two engines soon were developing 70 and 99 bhp on straight alcohol, instead of the pre-war petrol-benzol fuel, which was a really amazing output for such small powerplants. The reason for the alcohol fuel was not so much for any gain in performance, but rather because alcohol permits an engine to run much cooler than do more orthodox gasoline fuels. This cool running was deemed to be very important by the NSU technicians, as their plan was to run a fully streamlined shell over the bike which would limit the airflow to cool the engine.

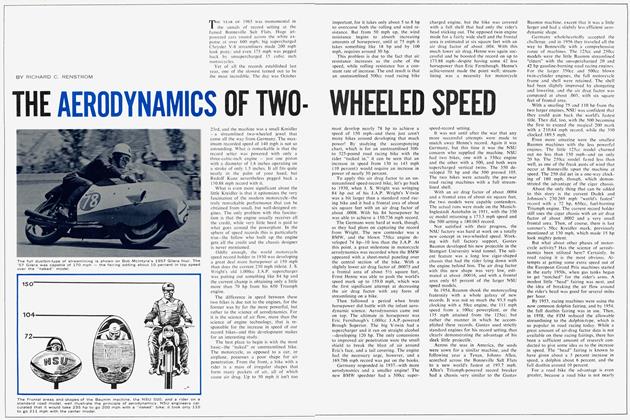

The next step was to design and build the streamlined shell for the twin. This was a major problem, because no research facilities were available to study airflow or other aerodynamic problems. Adopting an inexpensive and practical approach, the NSU technicians did their design work in a pond by towing various shapes of shells behind them in a hand rowed boat. By observing the wake left by the shell, it was possible to make small changes in the shape until the basic design was aerodynamically correct.

(Continued on page 38 )

Back at the race shop, the sheetmetal form was gradually molded into shape, and the beautiful blown engine was soon covered. Several previous record contenders had lost their lives at speed due to incorrect design of their shells; hence, the NSU technicians spent many months in testing and re-testing their design until they were convinced it would be stable at speed. In preliminary runs, Wilhelm achieved 150 mph, and, as all seemed well, in the spring of 1951, the new record contender was pronounced ready by the factory.

The morning of April 12 dawned clear and calm, with not a ripple of a breeze discernible. At 5:30 a.m. the 500-cc twin was fired up, the ripping roar of its exhausts shattering the quiet countryside. The engine was soon warmed up, and the technicians reported everything to be correct, so Herz set off down the road.

A tense silence then settled over the several thousand spectators who had gathered. All eyes were fixed on the small white object that approached down the Munich-Ingolstadt Autobahn. With a piercing howl from open exhausts and 8000 rpm, the NSU shot past and down the road. Soon Wilhelm returned on his run back through the clocks, and then the crowd waited for the time. In a few moments the loudspeakers crackled that Wilhelm had set a new world speed record for motorcycles at 180.065 mph — the first time that 3 miles had been covered in 1 min. on two wheels.

This new speed mark made the NSU camp jubilant, but it proved to be only the beginning of a great legend of speed. A few years later the title was taken away by an American using a British-built engine, so once again Wilhelm Herz laid out plans to recapture the record. By then, Herz and his NSU had become national idols, because German prestige had been greatly enhanced by their success in the world of speed. With this to motivate them, the NSU folk once again set the race shop humming with the honor of Germany at stake.

The goal this time became not only to gain back the speed title, but also to become the first to exceed the magical 200 mph mark on two wheels. The first step was to put the old engines on the test bed and obtain still more power. The research work soon proved successful. Output was pushed up to 75 bhp for the 350-cc engine, and 110 bhp for the 500-cc model.

Drawing upon all their previous experience, NSU engineers planned to run their motorcycles at the internationally famous Bonneville Salt Flat, Utah, USA. It was obvious to them that only at Bonneville could the full potential of their engines be exploited, because nowhere in Germany was there a road sufficiently long and level enough to obtain the absolute maximum speed. It was for this reason that output was raised to no more than 110 bhp, because running that far from home placed a heavy emphasis on the powerplant being perfectly reliable. In the event of a blown engine there would be no race shop conveniently at hand for repair work, so the quest for sheer power was thus tempered.

The next step was to build a new shell. For this the factory engineers went to the Stuttgart University wind tunnel to do their aerodynamic research. Herz was set on his bike in a crouched position, and the moulding of a shell around Wilhelm and his bike began. Altogether a total of 23 designs were tried until just the proper combination was found. The final design had a frontal area that was actually greater than the naked bike, but the much lower air drag factor of the shell gave a significant advantage to the streamliner. The frame, incidentally, was still the basic pre-war road racing unit with several inches added to the wheelbase for greater stability.

By 1956, the machines were pronounced ready, and in August the team arrived at Bonneville with a galaxy of models from 50-cc up to the big 500-cc supercharged model. For one full week, the NSU speedmen pounded the salt flat into submission. When they had finished, the record book had taken a dreadful thrashing. The runs were not without an incident, however, as Herz crashed at over 180 mph in a cigarshaped 250-cc model. He walked away from that one, and the next day the quest began for the elusive 200-mph mark.

When the runs began with the 500-cc model, named Delphin III, it was discovered that Wilhelm’s head and the cockpit roof made contact rather sharply due to the many bumps on the course. This was a real blow to the NSU plan, as the engineers had not expected such a rough course. The only answer was to remove the top of the cockpit shell, which upset the aerodynamics of the streamlining. A loss in speed was inevitable, and some concern was voiced about the stability at speed.

Herz was still confident, however. On the morning of August 4, the quiet of the Bonneville dawn was shattered by the scream of the blown twin’s exhaust. After a few preliminary, runs, the NSU was given its head, and the speed title once again belonged to Germany. The new record was 210.64 mph, the first time the double century mark had been achieved on two wheels.

There it is: Nineteen years after the design left the drawing boards of chief engineer Roder, it was still setting records. Truly, in the annals of all motorcycle sports there never has been an engine that has been so successful over so many years.

Serious students of motorcycle sport and history often are curious as to why such an engine could still be so modern and competitive. Was the NSU twin such a terribly complex, unusual or unique design? While it is true that the engine was certainly unique (only eight were built), the fundamental design really was quite straightforward and incorporated basic European motorcycle racing technology of the pre-war period.

When Roder first laid out his design, it was obvious that a single would never be suitable, because the uneven power impulses would make it nearly impossible to effectively damp the blower pressure. To go to the other extreme, to build a four-cylinder engine would make the aerodynamics a problem, because a Four is normally a very wide engine in a motorcycle frame. This extra width in the days before streamlined fairings came into use would have caused a greater air resistance factor than the twin, thus nullifying the small gain in horsepower the Four would have produced. So Roder settled for a twin, which he believed could be kept quite compact even with a supercharger, and yet would have a low reciprocating mass and short stroke, both of which permit high rpm.

A vertical twin it was, with a bore and stroke of 63 x 80 mm on the 500-cc engine, 56 x 70.5 mm on the 350. The crankcase was a cast alloy component with a separate oil tank also contained in the case; the entire unit was finned for heat dissipation.

The crankshaft was a built-up assembly with massive roller main bearings to withstand the pressure generated by supercharging. The solid steel rods also carried roller bearings at the big end. Pistons were three-ring alloy full-skirt units, moderately domed for an 8:1 compression ratio. Twin vertical shafts and bevel gears drove the two overhead camshafts. Hairpin valve springs were used.

The pre-war road racing engines used impeller superchargers. The post-war models were fitted with multi-vane blowers. The supercharger pulled air through a British Amal TT racing carburetor. A relief valve in the induction tube released excess pressure. The blower was chain driven as was the clutch. The Bosch magneto was gear driven.

Peak horsepower on this engine always was exceptional. In 1939, 65 and 90 bhp, respectively, were delivered. The two powerplants churned out 75 and 110 bhp, respectively, on straight alcohol fuel when NSU ran at Bonneville in 1956. Outputs of 8500 and 8000 rpm were produced on the two engines.

The chassis was quite orthodox for a 1938 grand prix machine. An old-style girder front fork was employed, and this was retained on the speed record models. The old girder fork lacked the suspension qualities of modem hydraulically damped telescopic forks, but did provide greater lateral rigidity for the wheel. NSU evidently believed this control and steering advantage at ultra-high speeds was more important than suspension quality, which is logical, considering the speed and smoothness involved on most speed record courses.

The frame was of wide duplex cradle configuration that had the old-style plunger rear suspension. The gearbox had four speeds. Final drive was by chain. Huge brakes were retained on the 1956 Bonneville models, a hangover from road racing days.

The fully streamlined models, used in 1956, were on the heavy side at 583 lb. with fuel. Overall length of the Delphin III was 145.7 in. Wheelbase was 63.5 in. Overall height was 43.7 in., with a width of 26.6 in. Special tires were built for the NSU at the Hanover works. The front was a 3.25-18, the rear a 3.50-20.

During technical development of the Delphin III some interesting data was assembled on the horsepower required to attain a certain speed. To achieve an even 200 mph on the naked NSU would have required something approaching 235 bhp. The air pressure on the rider would have been approximately 110 lb. It was obvious that 235 bhp could not have been obtained from a standard motorcycle engine; and a rider could never stay on the bike with 110 lb. of air pressure against him. Full streamlining was the only answer to surmount these obstacles.

In regard to the 1956 record assault by NSU, it seems odd that NSU did not mount its powerful blown twin in one of the long, low “cigar” shaped chassis developed in the Stuttgart University wind tunnels for the 50to 250-cc models. This cigar shape has been used by all Triumphpowered record setters since 1955. The long shell, with the rider lying prone, offers a great deal less wind resistance than does the full sized motorcycle with a shell. NSU considered this approach, but engineers stated at the time that they wished to see what they could do with a standard motorcycle type frame and 110 bhp.

During the past year there have been rumors that NSU desires to hold the “world’s fastest motorcycle” title once again. Some activity in the racing shop indicates that work is being done on the old pre-war supercharged engines. The speed record, now 245 mph, was set in 1966 with a cigar-shaped projectile that had two fuel burning 650-cc Triumph engines, which produced approximately 120 bhp. An NSU engineer recently stated the firm has extracted that much power from the venerable old 500-cc twin.

With 120 bhp in a cigar chassis, NSU engineers believe they may break the 300mph mark, which would be quite a feat on two wheels. For the present, however, they must be content to hold the official 500-cc world speed record, as well as the unofficial title of the world’s fastest true motorcycle. It is true that the NSU 500 remains the fastest motorcycle in the world with an orthodox frame and engine, and in which the rider sits in a normal position. All this speed and record setting is quite an achievement, particularly for an engine that is now 30 years old!