THE SCENE

IVAN J. WAGAR

ONE fellow who has more than his share of critics is Evel Knievel, the motorcycle jump artist. Handsome, intelligent and soft-spoken, Evel's pre-jump spiel is reminiscent of a fast-buck con-artist. His sales pitch often is followed by two or three false starts to put everyone in the mood. Skepticism often reaches fever pitch at this point. But strong men turn white and women scream when Evel starts up the ramp. And suddenly, regardless of the admission figure, everybody has his money's worth. Suddenly, there are no skeptics.

At Las Vegas, the Caesar’s Palace jump went badly. After soaring for 150 ft., and with the motorcycle set up for a good rear wheel landing, Evel landed on a flat van roof, a few feet short of the landing ramp. The impact was so severe that he lost the bars and crashed down the ramp, breaking so many bones that even he lost count. Evel is on the mend now. Fortunately, the badly damaged pelvic area did not require fusion, and he is continuing his plans for the Grand Canyon jump.

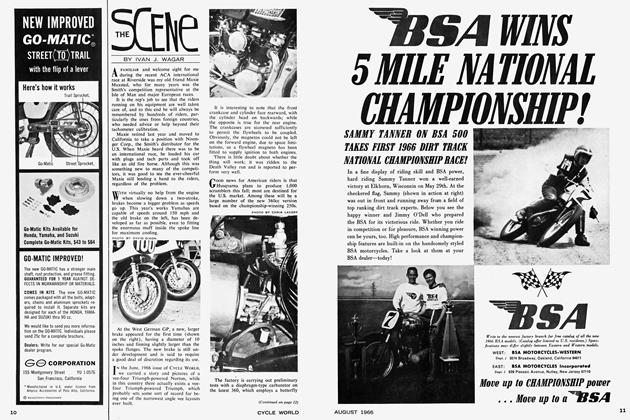

The accompanying photo is an artist’s rendering of Evel’s Skycycle. The designer is Alex Tremulis, who gained motorcycle fame as the designer of Bob Leppan’s 245-mph Gyronaut. Basic power for the Skycycle probably will be a Triumph engine. In addition, there will be two Turbonique rocket engines to provide a 3000-lb. boost. Evel reckons on 300 mph at blast-off, and has calculated that figure to be the minimum required to do the job. Will he do it? You can bet your boots he will!

PROBABLY little bent every or warped human one being way is or a another; some like skydiving, while at the other end of the scale there are those who collect stamps. Whatever a person’s bag is, I’m for it. And more power to him.

For the past 20 years, my bag, I admit, has been motorcycles, especially the unusual machines. There are plenty of fast motorcycles around, some of which truly are engineering masterpieces. The Honda Six and Yamaha Four are good examples of quarter-liter engines capable of more than 150 mph, but they are not, and never will be, for sale. Despite that fact, it does not take much time around these machines to form tremendous admiration for the people who build them.

Specials, frequently home built, can fall into the unusual category. Often constructed on shoestring budgets, the engines are nevertheless creditable pieces of work because they are different from those the big boys are producing for the masses.

With this little bit of ground work out of the way, it might be possible to understand my complete enthusiasm for the Yankee project during my recent trip to Spain. The motorcycle, as a whole, is a first quality machine. Magnesium hubs are now being cast in Ohio, and will be spoked up at the Schenectady plant. A massive tube bender has been installed at Yankee to facilitate frame production from the best tubing available. All fiberglass components are laid up with the latest resins to produce parts that are flexible, parts that never completely harden and become brittle.

The Yankee motorcycle, less engine, is an intriguing package of practical originality. When the engine is added, the picture becomes even brighter. The engine abounds with clever innovations and adaptations, and every thought and idea that has gone into the machine is there because it is believed that is the way Americans want their machines to be. Many corners could be cut, with a larger profit margin to the manufacturer, but the principles at Yankee prevent Mickey Mouse engineering or production becoming part of the project, even at the cost of a delay in engine production schedules.

Yankee President John Taylor insists that all production engines be built to the same standards as the machine I rode in Spain. However, the engine was a true factory prototype, with hundreds of man-hours involved in its construction, and the machine tools required to produce even small volume units are very complex.

The large central housing, for example, requires many machining operations to extremely close tolerances. On the prototype When the engine is added, the picture becomes even brighter. The engine abounds with clever innovations and adaptations, and every thought and idea that has gone into the machine is there because it is believed that is the way Americans want their machines to be. Many corners could be cut, with a larger profit margin to the manufacturer, but the principles at Yankee prevent Mickey Mouse engineering or production becoming part of the project, even at the cost of a delay in engine production schedules.

(Continued on page 46)

Yankee President John Taylor insists that all production engines be built to the same standards as the machine I rode in Spain. However, the engine was a true factory prototype, with hundreds of man-hours involved in its construction, and the machine tools required to produce even small volume units are very complex.

The large central housing, for example, requires many machining operations to extremely close tolerances. On the prototype engine, all of the work was accomplished on one machine, in a temperature/humidity controlled room. And the operation took almost two weeks of painstaking, highly skilled labor to complete. Now that the prototype engine has proved itself by running for considerable periods during the past two months, both on the test bed and in the motorcycle, the various boring and milling machines will be installed to initiate series production.

There have been many skeptics regarding the Yankee plan and there will be more. And it is a good thing there are pessimists about to keep overenthusiastic types in line. The Yankee is no longer a pipe dream. It is to be hoped the people involved have the courage to succeed regardless of whatever setbacks may come along. They are motorcyclists who are trying to build a machine that they also can ride and compete on, whether it be in the Six Days Trial, or at Daytona Speedway.

To insure the future of Yankee, John Taylor has, under the Yankee name, secured all U.S. distribution rights for Ossa motorcycles. The tieup is a natural; not only will the parts problem be solved, but also a Yankee dealer will have an excellent small displacement machine to fill out his model line. The Ossa West facility in Houston, Tex., will remain the port of entry. Schenectady, N.Y., will be the home office and eastern headquarters for parts and supplies. In addition, a completely new branch is to be formed in Southern California to service the West Coast. The future looks bright for Ossa, and it looks as if John Taylor will realize a dream shared for the past 30 years by many Americans.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Round Up

May 1968 By Joe Parkhurst -

The Service Department

May 1968 By John Dunn -

Letters

LettersLetters

May 1968 -

Ruin To Record

Ruin To RecordOut of the Rubble of World War Ii Came the Nsu Twin of Wilhelm Herz — the First Motorcycle To Break 200

May 1968 By Richard C. Renstrom -

Fiction

FictionThe Pickup

May 1968 By Robert Ricci -

Houston National

Houston NationalHouston National

May 1968 By Bruce Cox