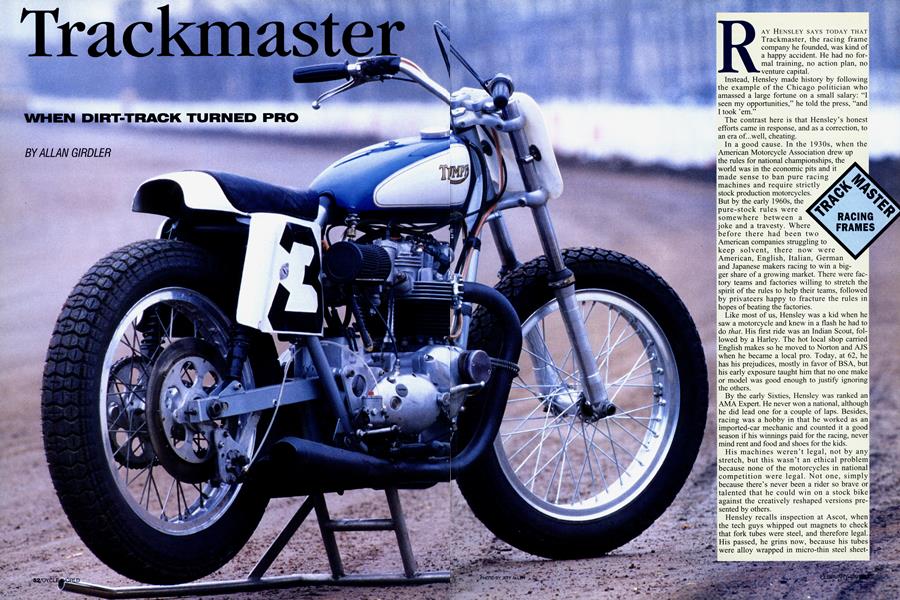

Trackmaster

WHEN DIRT-TRACK TURNED PRO

ALLAN GIRDLER

RAY HENSLEY SAYS TODAY THAT Trackmaster, the racing frame company he founded, was kind of a happy accident. He had no for mal training, no action plan, no venture capital. Instead, Hensley made history by following the example of the Chicago politician who amassed a large fortune on a small salary: "I seen my opportunities," he told the press, "and I took `em."

The contrast here is that Hensley's honest efforts came in response, and as a correction, to an era of...well, cheating.

In a good cause. In the 1930s, when the American Motorcycle Association drew up the rules for national championships, the world was in the economic pits and it made sense to ban pure racing machines and require strictly stock production motorcycles. But by the early 1960s, the pure-stock rules were somewhere between a joke and a travesty. Where FR before there had been two American companies struggling to keep solvent, there now were American, English, Italian, German i and Japanese makers racing to win a big ger share of a growing market. There were fac tory teams and factories willing to stretch the spirit of the rules to help their teams, followed privateers happy to fracture the rules in hopes of beating the factories.

Like most of us, Hensley was a kid when he saw a motorcycle and knew in a flash he had to do that. His first ride was an Indian Scout, fol lowed by a Harley. The hot local shop carried English makes so he moved to Norton and AJS when he became a local pro. Today, at 62, he has his prejudices, mostly in favor of BSA, but his early exposure taught him that no one make or model was good enough to justify ignoring the others.

By the early Sixties, Hensley was ranked an AMA Expert. He never won a national, although he did lead one for a couple of laps. Besides, racing was a hobby in that he worked as an~ imported-car mechanic and counted it a good season if his winnings paid for the racing, never~ mind rent and food and shoes for the kids.

His machines weren't legal, not by any stretch, but this wasn't an ethical problem because none of the motorcycles in national competition were legal. Not one, simply because there's never been a rider so brave or talented that he could win on a stock bike against the creatively reshaped versions pre sented by others.

Hensley recalls inspection at Ascot, when the tech guys whipped out magnets to check that fork tubes were steel, and therefore legal. His passed, he grins now, because his tubes were alloy wrapped in micro-thin steel sheeting. The next guy in line might have sprayed his alloy tubes with liquid steel, and the guy behind him might have made the entire frame out of thinner steel of a better grade, so it was stronger and lighter than the stock version. -

An engine's mounting plates might have been redone, to locate the engine where the weight would help traction. Not by much, not enough to be noticed except by someone who really knew his stuff, which Hensley says most inspectors didn't A Harley guy might have a front cylinder displacing the legal 375cc, with a rear one of 45 0cc, because he knew the inspectors always checked the front and never the back.

ES This got so bad that the AMA, pres sured surely by the factories, finally did the right thing, threw up their hands and said okay, racing frames will be legal, if they're insnected and certified

`V 111 Ullu At the time, Hensley had his eye on Honda's 250cc four-stroke Twin. It was a terrific engine but flat-track bikes back then used rigid rear ends and carefully limited forks, while the stock Honda had just enough bad suspension to be hopeless on dirt. So Hensley made a racing frame for the Honda engine. No textbook, no CAD-CAM, not much theo ry. This was 1965 and there wasn't a lot of theory to study.

The engine location, steering-head rake and so forth came from educated guess. "We'd been run ning our Gold Stars into curbs (a quick and effective way to shorten the wheel base, steepen the rake and speed up the steering)," Hen sley says, which was about it as far as ad vanced frame-geom etry research.

For the Honda 250 frame, Hensley used 4150 steel, the best on the market, and took his time with the welds. He gives the AMA credit here, in that they'd flunked some designs, but his was good and looked it, and passed a genuine inspection. Betting on his good ideas, Hensley went from track to track, week after week, hawking the frame like the peanuts seller at a ballpark. It was an uphill effort. "All the riders said, `Get somebody to run it, and if it does well maybe I'll be interested," he remembers.

Then came the break. Just about every motorcycle maker selling in the U.S. wanted into dirt-track. Most had their own operations and weren't looking for outside help. But ______ Suzuki was new, had a promising engine from the X-6 Hustler and a good rider in Rick Woods (who later earned fame in speedway) Hensley matched his frame and components to Suzuki's engine, the combo won first time out and the other guys took I note. Hensley began selling frames under the name Sonicweld-this was early in the Space Age, remember-but it was still a garage-band operation.

Then came the second big break. Gary Nixon knew Hensley from the track, where (we can guess, this isn't something either man would say) he saw Hensley was more tuner than rider. Nixon had BSA backing, but he reckoned they didn't know every thing, so he loaned Hensley $1000-which meant a rent ed building, a staff and the equipment needed to really go into business. Which

Hensley did in 1969, using the Trackmaster name.

To Nixon's further credit, business was business and the very first Trackmaster frame went to Gene Romero, who was to Triumph what Nixon was to BSA, never mind that BSA and Tnumph got along like, oh, Harley and Indian.

Nixon grumbled, Hensley says nearly 30 years later, but he understood and he kept his order in and his loan out. And, of course, the machines worked. Nixon was twice national champion and Romero won once-take that Harley and Norton and Yamaha and Honda, etc. .

The actual Trackmaster design was cheerfully empir ic. The very early examples were rigid rear, that being the way it was done at the time, with steering rake, wheelbase, engine location and frame stiffness all pat terned on what Hensley had seen work and not work.

Nor was Trackmaster the first to use a massive back bone or to take advantage of its bulk to carry engine oil. It simply worked, so Hensley did it. When rear suspension arrived, Trackmaster went with it, an advantage here being that Hensley was aware of the importance of swingarm-pivot location years before the subject went public.

Business boomed-from factories and privateers. Just about the only major brand not standing in line was Harley-Davidson. Trackmaster did make Harley frames and they worked, but the H-D crowd had their own sources of supply and they didn't always like to share as much as the team concept suggests, so riders like Mert Lawwill and Mark Breisford rode their own frames.

And there was politics. Sometimes-witness Nixon stay ing cool when Romero got the frame first-personalities didn't interfere. And sometimes they did. Hensley recalls

one rider who was backed by Triumph and who was supposed to get Trackmaster help. The racer borrowed one of Hensley's own bikes and when it came back the special tires Hensley had been saving were gone. The racer was vague as to what hap pened. Hensley made sure that man never rode Trackmaster equipment again.

Growing pains also figured into the equation. Hensley had a large and expanding family and he wasn't pleased with what life in the city was becoming. He liked the outdoors, especially the Canadian wilderness, so he moved his family from California to a camp in Ontario, expecting to run his business via remote control.

"I had delusions of grandeur," he ruefully reflects now. Hensley recalls two kinds of employee: those who wanted to do well but weren't good enough at it, and those who wanted to take advantage and excelled.

Making an unhappy story short, the disgruntled and devi ous workers went off and founded a frame company of their own, which didn't do all that well. The loyal guys bought out Trackmaster, but it, too, fell victim. Hensley, mean while, signed on with a Canadian mining company, which took him away from his own wilderness into the rest of the Great White North, but paid the bills.

The problem with Trackmaster had nothing to do with the product, it was just that by the mid-'70s, winning on Sunday no longer translated into selling on Monday. BSA and Triumph and Norton had been so badly managed and fallen so far behind the times that they went out of business, taking with them the 5l~~ factory teams and the contracts.

2 S Yamaha filled part of the gap, taking over the role of anti-Harley and doing a good job at it. Trackmaster did some work for Yamaha in the early days, but Hensley's pal Shell Thuett got the factory contract, and then Yamaha, too, dropped out of the Grand National game.

V Then came motocross. There was a tremendous off-road boom in the late 1960s, early 1970s. Erstwhile MXers could go to the store and buy a racing machine off the floor, ready to race or be improved, no secret passwords needed, just like dirt-track had been back in the 1930s. This was great for racing and the average racer, but it didn't do much for firms like Trackmaster-or Redline or Champion, rivals for the now-shrinking pie. The market for frames darn near disappeared.

Hensley made one more try. He was offered financial backing so he came back to the U.S. and went into business as Starracer, offering frames for any engine certified for competition. Some orders came in, but the demand was low and Hensley says the business side was poorly run so that operation also shut down.

But the story has a happy ending. Motorcycle racing is the most cyclical of sports. The Grand National Championship became smaller and more professional, requiring extra technology and money, but about the time old racebikes became rare and fragile.. .they became valuable. We invented vintage racing.

Hensley found himself plagued, well, better make that pursued, by guys who'd found old Trackmasters in the back of their shops, or got them from their dads or something. These new guys were matched by old guys who'd kept the machines and suddenly discovered there was something to be done with them again.

The vintage guys needed parts and advice. Hensley wasn't shy with either. Plus, he looked around and couldn't find anybody using the name Trackmaster, so he filed a "Doing Business As..." statement, nobody objected, and he got his brandname back.

The sign on the shop, on the outskirts of Hesperia, California, at the edge of the high desert, says Ray Hensley's Innovations, but that's kind of a disguise, because the cards and the ads say Trackmaster.

His experiences haven't been wasted. Like any prudent contractor, Hensley has slightly overbooked himself. His shop, staffed this time with loyal employees-his son, for instance-has more orders than it can keep up with. Most of the work is what you'd expect, as in frames for BSA and Triumph Twins. Vintage rules require period specifications; the design has to be the same and there are limits on suspen sion travel, but there's nothing in the book says you can't make a frame now that looks just like it would have if it'd been made in 1970.

Meanwhile, vintage-race organizations such as ARHMA and VDTRA are putting on Amateur and Semi-Pro events coast to coast and all those classic engines have, so to speak, someplace to go.

And we have Ray Hensley and Trackmaster to thank for it.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue