THE HISTORY OF SUZUKI

ONE OF THE most fascinating aspects of motorcycle history is the study of the many important innovations in design that have occurred over the years. Many companies all over the world have played an important role in this evolution of the motorcycle, and a particularly brilliant idea has often been the cause of a company or country taking the lead on both the sales floor and the world’s great racing courses.

It is an interesting point of motorcycle history that often the company which invents a particular design feature has not always been the marque that develops it into a sales leader. This is particularly true of the Japanese manufacturers, who have all developed a formidable sales rate using many design innovations that were created many years earlier.

One of the foremost examples of this has been Suzuki-a marque that is, perhaps, more responsible than anyone for making the two-stroke engine an acceptable proposition to the public.

The story of this enterprising Japanese concern actually began many years ago when the Suzuki Loom Works was founded at Hama-

founded at Hamamatsu in 1909. In 1920 the expanding company was renamed the Suzu-

ki Loom Manufacturing Company Ltd., and in 1939 a modern plant was built to keep up with the demand.

Then came the war, after which followed a period of rebuilding and economic instability. Faced with a declining textile business, Shunzo Suzuki was casting about for something new to produce. The idea finally hit him one fall day in 1951 when he was bicycling home from a fishing trip. Why not produce a motor for his bicycle?

This idea really wasn’t all that brilliant, since well over 100 other Japanese

companies were trying to do exactly the same thing. Mechanized transportation was very scarce in Japan then and the people were poor. A cheaply produced motorbike would certainly meet with an eager market. The big problem was that the country possessed little technical knowledge of how to produce good cars

or motorcycles, and a chaotic financial structure made it difficult for the company to purchase tools and establish prod uction.

As it transpired, only five of these companies were destined to survive. In the process Suzuki became the world’s largest producer of two-stroke machines, and has blazed a brilliant record in international competitions. Today the company produces small cars and trucks, outboard motors, and other industrial items. The Emperor of Japan has honored Michio Suzuki and his son

Shunzo with the Blue Ribbon Medal for significant contributions to the country.

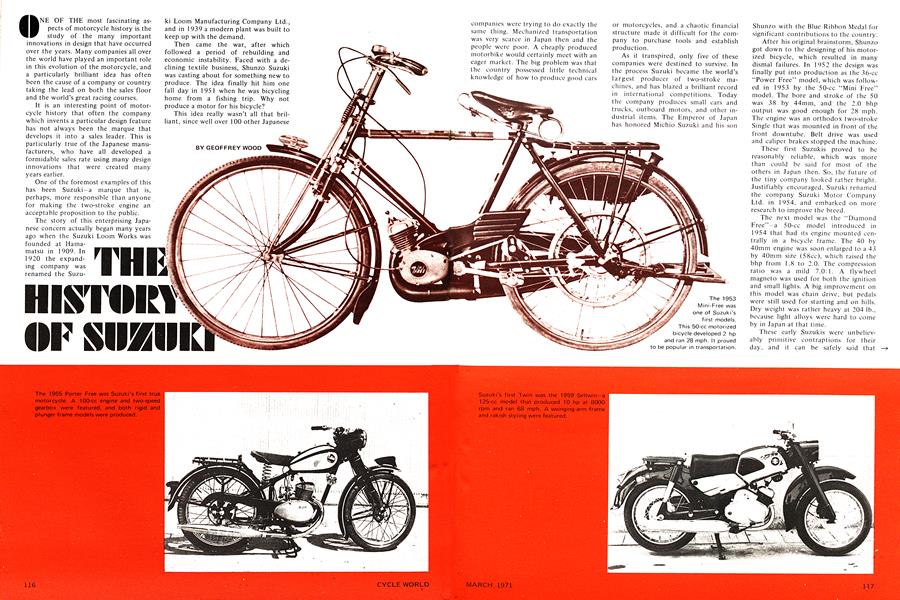

After his original brainstorm, Shunzo got down to the designing of his motorized bicycle, which resulted in many dismal failures. In 1952 the design was finally put into production as the 36-ec “Power Free’’ model, which was followed in 1953 by the 50-cc “Mini Free” model. The bore and stroke of the 50 was 38 by 44mm, and the 2.0 blip output was good enough for 28 mph. The engine was an orthodox two-stroke Single that was mounted in front of the front downtube. Belt drive was used and caliper brakes stopped the machine.

These first Suzukis proved to be reasonably reliable, which was more than could be said for most of the others in Japan then. So, the future of the tiny company looked rather bright. Justifiably encouraged, Suzuki renamed the company Suzuki Motor Company Ltd. in 1954. and embarked on more research to improve the breed.

The nexi model was the “Diamond Free”-a 50-cc model introduced in 1954 that had its engine mounted centrally in a bicycle frame. The 40 by 40mm engine was soon enlarged to a 43 by 40mm size (58cc). which raised the blip trom 1.8 to 2.0. The compression ratio was a mild 7.0:1. A flywheel magneto was used for both the ignition and small lights. A big improvement on this model was chain drive, but pedals were still used for starting and on hills. Dry weight was rather heavy at 204 lb., because light alloys were hard to come by in Japan at that time.

These early Suzukis were unbelievably primitive contraptions for their day, and it can be safely said that

Japanese designers were at least 35 years behind the Europeans. In 1955 Goeff Duke lapped the Isle of Man just shy of 1 00 mph on a dohc, four-cylinder Güera. Moto Guzzi was using a wind tunnel to perfect their streamlined shells then, and Norton had produced their famous “Featherbed” frame some four years earlier. Despite the antiquity of their designs, Suzuki would, within eight years, challenge the pride of Europe on the classical grand prix courses.

These first Suzukis gave the company a firmer financial base and the engineers had a modest reservoir of knowledge to draw upon. More effort was put into research and the first evidence of this came in 1955 when the new “Porter Free” model was introduced. This 100-cc Single was the first true motorcycle produced by Suzuki. It proved to be an exceptionally sound design as well as a great milestone in the history of the company.

The new Porter had a bore and stroke of 52 by 48mm, and it pumped out 4.2 bhp at 5000 rpm on a 7.0:1 compression ratio. A flywheel magneto provided current for both ignition and lighting, and an alloy head was used in conjunction with an iron cylinder.

The Porter Free was more modern with a foot shift and hand clutch, but the two-speed gearbox with ratios of 12

and 18:1 didn’t provide very impressive performance. Weight was 187 lb., and the maximum speed was 37 mph. Tire size was rather odd at 2.50-24, but a new telescopic front fork made the Porter Free appear more modern. This model was produced in both rigid and spring frame versions, the springer having plunger type rear suspension. The Porter Free did have clean, attractive lines and it possessed an appearance similar to the post-war CZ 125-cc models.

Suzuki moved rapidly during 1956 and 1957. New 125 and 250 “Colleda” Singles were introduced that looked more modern with their heavier frame, plunger rear suspension, and stronger front fork. A headlight nacelle was even tried that bore a striking resemblance to the British Triumph, and these models sold as never before. The future of Suzuki seemed assured.

In 1958 the company began mass producing motorcycles on an assembly line basis. This was the work of Shunzo after becoming president in 195 7. The number of models was limited to three sizes (50, 125, and 250cc) in an effort to streamline operations to keep up with the demand, and more effort was put into research.

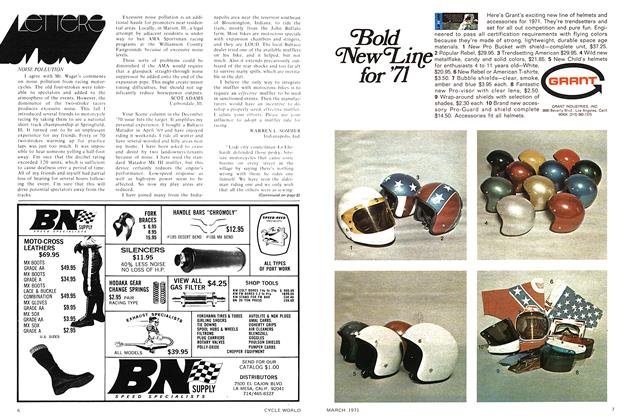

In 1959 the company made another great stride forward when they introduced their first Twin, the 125-cc “Seltwin.” This model set a new trend in comfort with its swinging-arm rear suspension, and the silky smooth engine churned out 10 bhp at 8000 rpm. Bore and stroke was 42 by 45mm and the compression ratio was 7.0:1. The wheelbase was 51.0 in. Tire size was 2.75-17. This high revving Twin would clock 68 mph, and it ushered in an era of high

speed engines that has become a hallmark of Japanese motorcycles. For this reason alone, the Seltwin is an important milestone in the history of the Japanese industry, and it shows just how fast they were moving.

In 1959 the company also produced the “Suzu Moped” in an effort to provide a really inexpensive mode of transportation. This 50-cc Single churned out 2.2 bhp at 5000 revs. Power was transmitted through a belt drive. The belt was later dropped in favor of chain drive. This model proved to be exceedingly popular in Japan due to the heavy traffic and low incomes of the people.

During the next few years Suzuki

continued to improve their machines. Pressed steel frames and forks were tried in an effort to cut production costs while providing a more modern appearance. It was during this time that Suzuki, like other Japanese manufacturers, acquired the rather ungainly fuel tanks that were featured until the late 1960s. A great deal of research also went into designing better engines and gearboxes.

The 50-cc mopeds continued to be the big seller in Japan, but in 1961 the company began production of their 360-cc light truck. Suzuki also opened their London office in an effort to penetrate the European market. A U.S. branch followed in 1963.

Suzuki models produced then were good routine transportation machines. This was all that was needed in order to sell in Japan. Riders around the world

were interested in a little more sporting proposition, however, since they had been fed a steady diet of road races, motocross, and trials for many years. Realizing this, it is no surprise that Suzuki did not take the world by storm.

Typical of the early 1960 Suzukis was the 125-cc "SL,” a Single that churned out 8.0 blip at 6000 revs and ran 56 mph. The SL was heavy at 246 lb., and with a four-speed gearbox, it did not provide very spirited performa nee.

The challenge was two-fold build more sporting bikes and then get Suzuki known throughout the world. This, of course, was no easy chore, since their motorcycles were unknown outside of Japan until the early 1960s when Honda first went racing in Europe. The only answer was. of course, to do just like Honda go racing to get known, which in turn would provide technical knowledge to improve their roadster models.

The first mention of Suzuki in the racing annals of Europe occurred in 1960 when the marque made their way to the Isle of Man to compete in the ultra-lightweight TT. In contrast to all the interest shown in Honda in 1959, Suzuki was hardly mentioned by the journalists, mostly because two-strokes had inferior performance.

The bikes were cobby looking 1 25cc Twins with an orthodox piston-port design, but beyond that not much is known about them. Even then Suzuki exhibited a trait that would be with them all during their racing daysalmost total secrecy concerning the technical specifications of their racing machines.

In the TT itself, Suzuki riders T.

Matsumoto, M. Ichino, and R. Fay finished in 15th, 16th, and 18th places. This was a superb demonstration of reliability, but the 71.88 mph speed was well below the 85.6 mph speed of Carlo Ubbiali's MV Agusta. Matsumoto was also well below the 80.08 mph speed of Naomi Tanaguchi on his Honda Twin. Suzuki obviously had a great deal to learn. Undaunted, they returned to Japan to develop a real racing engine.

In 1961 Suzuki returned to Europe, this time with rotary valve 125 and 250ce Twins that had "borrowed” the disc valve idea from the fast but unreliable East German MZs. Little is known of the technical specifications, but they were faster and less reliable! By then Suzuki realized that they would need some good riders if they were to have any chance at success, so they hired Hugh Anderson of New Zealand and Alastair King of Scotland to ride their bikes.

In the 1 25-cc TT all the Twins came unglued at the seams, and King also found a mechanical weakness in the 250 machine. Anderson and Ichino managed to struggle home in 10th and 12th positions, but the 8 2.5 mph speed was pitiful when compared to Mike Hailwood’s 98.38 mph average on his Ho nda.

The Suzuki team also had a bash at the Dutch Grand Prix, held at Assen just after the IOM. Ichino, M. Itoh, and Matsumoto came home in 14th, 16th, and 17th positions, but none of the 250s managed to finish the event. After this the team returned to Japan.

Late in 1961 Suzuki was able to hire Ernst Degner away from MZ, which was a real advantage for two reasons. First,

(Continued on page 128)

Continued from page 119

Degner was a very good rider. Secondly, he was a brilliant engineer. During the long winter this team toiled to build their racing bikes, which included a tiny 50-cc Single for the new “tiddler” class plus a 125-cc Single and a 250-cc Twin.

Suzuki showed up in force for the TT, and Degner made history when he won the first 50-cc TT at a shattering 75.12 mph. Itoh and Ichino finished 5th and 6th. This was the first win by a two-stroke since 1938 when Ewald Kluge won the 250 TT at 78.48 mph on a blown rotary-valve, water-cooled DKW split-Single. In the 125-cc TT Degner finished eighth at 84.14 mph-well below^ Luigi Taveri’s 89.88 speed on a Honda. None of the 250s finished the race.

On the continent, Degner had a great year with the screaming 50, winning the Dutch and Belgian Grand Prix. This gave him enough points to be crowned world champion, which was the first time that a two-stroke had won the world title since its inception in 1949.

In the 125 and 250 classes Degner, Frank Perris, Hugh Anderson, Ichino, and Itoh gained many good places, but the Honda 125 Twins and 250 Fours were just too fast and reliable. The only answer was more research. So, factory engineers produced new 50 and 125-cc racers that at first were air cooled, but soon sprouted water cooling. The 250 class, for the time being, was ignored.

These new racers were much faster, and Suzuki started off a great year with smashing wins in the 50 and 125-cc TT events. The team of Degner, Perris, Bert Schneider, and Ichino simply dominated these two classes to give Anderson both of the titles.

The following year Honda came out with their 16,000 rpm 1 25-cc Four with an eight speed box. This proved to be too much for Suzuki to match. Anderson held onto the 50-cc title, but late in the season Honda brought out a faster 50-cc Twin. -The only answer was to build a Twin. In 1966, after a year of development, Georg Anscheidt captured another 50cc title for Suzuki.

The water cooled 125, meanwhile, was steadily improved, and in 1965 Anderson and Perris finished 1-2 in the championship ahead of the 34 bhp Hondas. In 1966 Yamaha got their two-stroke going and it was a threeway battle. Suzuki finished 3rd after a torrid season.

Meanwhile, Suzuki was designing a unique bike to get back into the 250

class. The basic design was a 43 by 42.6mm rotary valve Four, with the cylinders and crankshafts set in a square position, much the same as that great classic, the Ariel “Square Four.” Water cooling was used, and there were three transfer ports per cylinder and single ring pistons.

The two crankshafts were mounted transversely to the frame and were coupled together by large gears in the center of the block. The front shaft turned forward and the rear shaft backward-thus achieving a counteracting balance factor. The clutch was driven off the right side gearbox input shaft. The final drive sprocket was on the left. Both fiveand six-speed gearboxes were used, depending on the circuit.

Due to a lack of braking compression, the Four had an immense double front brake. Each unit had twin leading shoes. The frame was a wide duplex cradle type, and the whole bike was rather low but wide due to the engine shape. Dry weight was remarkably light at 286 lb.

The first Four was completed and tested in late 1963, at ,which time it produced a little over 50 bhp at 12,500 rpm. Carburetor size was 22mm, and a gas oil ratio of 20 to 1 was used. The power band was quite narrow, with real power available at about 10,000 revs, although the engine would pull well from 8500 rpm.

During 1964 the factory experienced a great many failures with their brainchild, as is often the case with a new and complex design. In the Spanish GP Anderson finished 5th, while Schneider gained a 3rd in the French and 6th in the Ulster. For 1965 Suzuki added an auxiliary oil pump to get extra lubrication to the rod big-ends. An improved ignition and better brakes made the Four more competitive. Perris finished 3rd in the TT that year plus 5th in the Belgian. Newcomer Yoshimi Katayama gained 4th in both the Dutch and Belgian events. In the fast Belgian GP Katayama averaged 1 17.7 mph-respectably close to Jim Redman’s 120 mph speed on the Honda Four.

For 1966 Suzuki decided to drop the 250 class and concentrate on smaller machines, perhaps because the expenses had become exorbitant and the competition brutal. The Four, despite its brilliant design, had proven to be temperamental. In addition, the factory never did have riders with quite the class of Mike Hailwood and Phil Read. In the 50-cc class Suzuki was still champion with Hans-Georg Anscheidt on board their 17.5 bhp Twin, but Anderson and Perris found their 125s outsped by the new Honda 36 bhp 125 and the Yamaha 40 blip Four.

In 1967 and 1968 Anscheidt continued to hold on in the 50-cc class, but \

Stuart Graham could not quite edge out

Continued from page 128

the 125 Yamahas despite winning his share of the races. Suzuki then decided that they had achieved what they wanted in the way of worldwide fame and technical knowledge, so they began to pull out of grand prix racing. In 1968 they did not field any 50-cc models, and their only 1 25 effort was to loan a racer to Anscheidt for a few events.

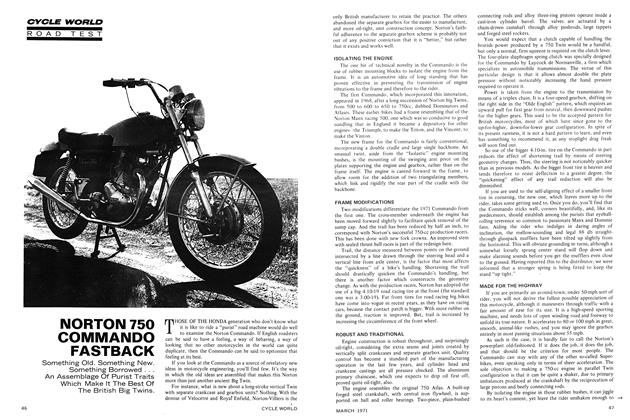

All of this research on their racing bikes provided a great deal of technical knowledge that was soon applied to the roadsters. The first real indication of this was the 1965 X-6 model, a 250-cc Twin with an exceptionally advanced design. The big news with the X-6 was the six-speed gearbox that provided searing acceleration from the 29 bhp engine. The other big item was the “Posi-Force” lubrication system that consisted of an oil tank and a pump that put the oil directly into the main bearings. This device did away with messy gas and oil ihixing, and it provided superior lubrication to the lower end.

It should be pointed out that Suzuki was not really first, since the 1912 Matchless TT bikes had a six-speed box and the Velocette GTP two-stroke of the 1930s had a positive oiling system. Another analogy is Suzuki’s 1967 500-cc, five-speed Twin, which was preceded way back in the 1 930s by DKW’s big two-stroke Twin. Perhaps the really significant thing is that the new Suzukis are really outstanding machines with exceptional reliability, as has been proven in countless production machine endurance races around the world. A great deal of technical knowledge of thermo-dynamics, metallurgy, and lubrication has been adopted from the racing research, so that today the marque produces a wide range of models with sophisticated specifications.

In the U.S., production racing was just becoming popular on the West Coast in 1965, and the X-6 proved to be just the thing for the 250 class. In February of 1966, U.S. Suzuki decided to have a go at Daytona and prepared three 250 X-6 models. The potential shown by these machines was astounding, but minor ignition problems stopped the effort.

During the following two years, developments improved the X-6 into a really competitive machine. But, it was soon to be overshadowed by the introduction of the largest two-stroke Twin in current production, the T500 Titan.

Ron Grant got the ball rolling in the States by outfitting a T500 for racing by installing the engine in a Rickman

frame. Even though the machine only handled fairly well, the engine’s reliability was evident. The factory showed interest and 1969 saw the first T500 road racers to come to these shores.

What happened is a matter of record. The Suzuki team of Ron Grant, Art Baumann and Jim Odom ran near the front of the 200 miler at Daytona with Grant eventually finishing 2nd. Other successes by the big Twins that year included a 5th at Loudon, 2nd and 3rd at Indianapolis and Art Baumann’s first ever win for a two-stroke in big bore AMA road racing at the 125-mile Sears Point National.

A new batch of T500 road racers came to the States in 1970. and a new team member, Jody Nicholas, joined Ron Grant and Art Baumann in their assault on AMA road racing. After running out of gas while leading at Daytona, Ron Grant scored a decisive victory at Kent, Washington. Jody finished 2nd at the 200 mile national at Talledega, Ala.

Back in California, the T500s set many lap and race records at local road race courses. Their unfailing reliability previews the 1971 season.

Another chapter in the company’s history is their new found love for motocross racing. The first serious interest in this rough and tumble sport came in 1968 when the TM250 was produced in limited numbers for selected riders. This lusty Single had a bore and stroke of 66 by 73mm, and it churned out 3 2 bhp at 6800 rpm using an 8.0:1 compression ratio and a 26mm carburetor. Dry weight was about 230 lb. and a long 52.7 in. wheelbase was used. These scramblers went well but were not outstanding, so the factory did more research into the designing of a motocross bike.

By the spring of 1970 the new bikes were ready, and Joel Robert and Sylvain Geboers were invited to test them in Japan. The Europeans were so impressed that they signed on the spot. Almost overnight Suzuki was ready to challenge the might of Europe.

Two new models were produced, a 250 and a 367. Both have fivespeed gearboxes, and the weight is known to be very light —about 189 lb. for the 250 and 202 lb. for the 367. While technical data is still kept rather secretive on these bikes, it is known that they produce about 34 bhp at 7000 rpm and 38 bhp at 6500 rpm. The engines have a standard piston-port design, and the bikes follow orthodox European styling.

Suzuki decided to limit themselves to the 250 class for 1970, and Geboers and Robert ran 1st and 2nd in the championship nearly all season long. By winning nearly every event, the traditional European domination of motocross was broken and Japan is now a leader i n t h a t sphere. [O]