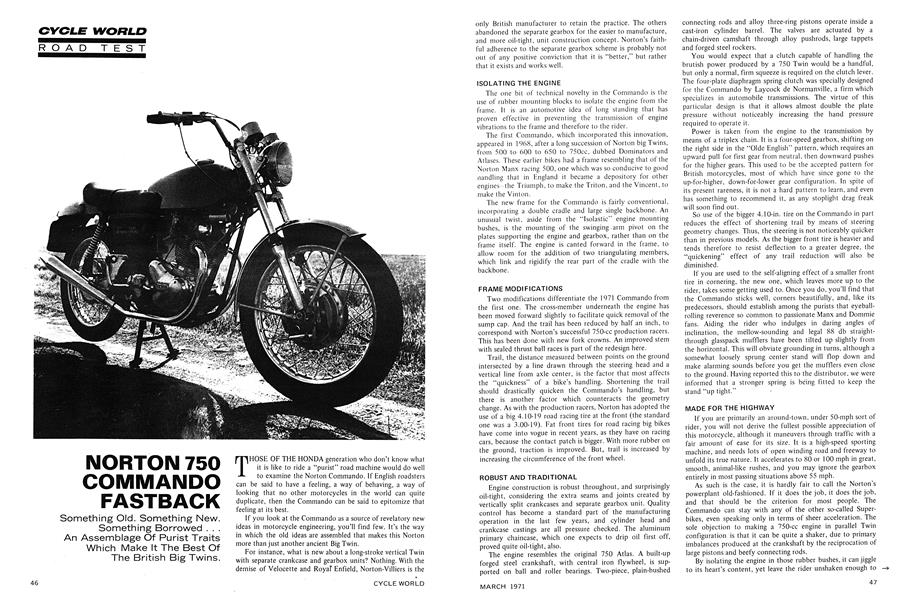

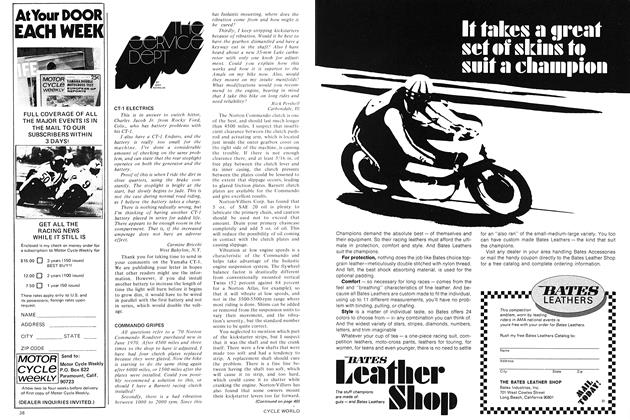

NORTON 750 COMMANDO FASTBACK

CYCLE WORLD ROAD TEST

Something Old. Something New. Something Borrowed . . . An Assemblage Of Purist Traits Which Make It The Best Of The British Big Twins.

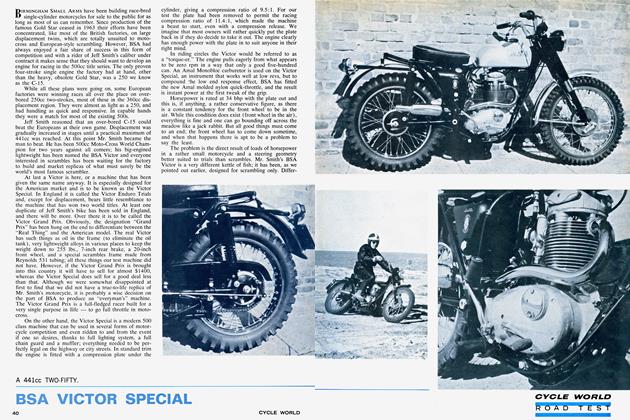

THOSE OF THE HONDA generation who don’t know what it is like to ride a “purist” road machine would do well to examine the Norton Commando. If English roadsters can be said to have a feeling, a way of behaving, a way of looking that no other motorcycles in the world can quite duplicate, then the Commando can be said to epitomize that feeling at its best.

If you look at the Commando as a source of revelatory new ideas in motorcycle engineering, you’ll find few. It’s the way in which the old ideas are assembled that makes this Norton more than just another ancient Big Twin.

For instance, what is new about a long-stroke vertical Twin with separate crankcase and gearbox units? Nothing. With the demise of Velocette and Royaf Enfield, Norton-Villiers is the

only British manufacturer to retain the practice. The others abandoned the separate gearbox for the easier to manufacture, and more oil-tight, unit construction concept. Norton’s faithful adherence to the separate gearbox scheme is probably not out of any positive conviction that it is “better,” but rather that it exists and works well.

ISOLATING THE ENGINE

The one bit of technical novelty in the Commando is the use of rubber mounting blocks to isolate the engine from the frame. It is an automotive idea of long standing that has proven effective in preventing the transmission of engine vibrations to the frame and therefore to the rider.

The first Commando, which incorporated this innovation, appeared in 1968, after a long succession of Norton big Twins, from 500 to 600 to 650 to 750cc, dubbed Dominators and Atlases. These earlier bikes had a frame resembling that ot the Norton Manx racing 500, one which was so conducive to good Handling that in England it became a depository for other engines -the Triumph, to make the Triton, and the Vincent, to make the Vinton.

The new frame for the Commando is fairly conventional, incorporating a double cradle and large single backbone. An unusual twist, aside from the “Isolastic” engine mounting bushes, is the mounting of the swinging arm pivot on the plates supporting the engine and gearbox, rather than on the frame itself. The engine is canted forward in the frame, to allow room for the addition of two triangulating members, which link and rigidify the rear part of the cradle with the backbone.

FRAME MODIFICATIONS

Two modifications differentiate the 1971 Commando from the first one. The cross-member underneath the engine has been moved forward slightly to facilitate quick removal of the sump cap. And the trail has been reduced by half an inch, to correspond with Norton’s successful 750-cc production racers. This has been done with new fork crowns. An improved stem with sealed thrust ball races is part of the redesign here.

Trail, the distance measured between points on the ground intersected by a line drawn through the steering head and a vertical line from axle center, is the factor that most affects the “quickness” of a bike’s handling. Shortening the trail should drastically quicken the Commando’s handling, but there is another factor which counteracts the geometry change. As with the production racers. Norton has adopted the use of a big 4.10-19 road racing tire at the front (the standard one was a 3.00-19). Fat front tires for road racing big bikes have come into vogue in recent years, as they have on racing cars, because the contact patch is bigger. With more rubber on the ground, traction is improved. But, trail is increased by increasing the circumference of the front wheel.

ROBUST AND TRADITIONAL

Engine construction is robust throughout, and surprisingly oil-tight, considering the extra seams and joints created by vertically split crankcases and separate gearbox unit. Quality control has become a standard part of the manufacturing operation in the last few years, and cylinder head and crankcase castings are all pressure checked. The aluminum primary chaincase, which one expects to drip oil first off, proved quite oil-tight, also.

The engine resembles the original 750 Atlas. A built-up forged steel crankshaft, with central iron flywheel, is supported on ball and roller bearings. Two-piece, plain-bushed

connecting rods and alloy three-ring pistons operate inside a cast-iron cylinder barrel. The valves are actuated by a chain-driven camshaft through alloy pushrods, large tappets and forged steel rockers.

You would expect that a clutch capable of handling the brutish power produced by a 750 Twin would be a handful, but only a normal, firm squeeze is required on the clutch lever. The four-plate diaphragm spring clutch was specially designed for the Commando by Laycock de Normanville, a firm which specializes in automobile transmissions. The virtue of this particular design is that it allows almost double the plate pressure without noticeably increasing the hand pressure required to operate it.

Power is taken from the engine to the transmission by means of a triplex chain. It is a four-speed gearbox, shifting on the right side in the “Oldc English” pattern, which requires an upward pull for first gear from neutral, then downward pushes for the higher gears. This used to be the accepted pattern for British motorcycles, most of which have since gone to the up-for-higher, down-for-lower gear configuration. In spite of its present rareness, it is not a hard pattern to learn, and even has something to recommend it, as any stoplight drag freak will soon find out.

So use of the bigger 4.10-in. tire on the Commando in part reduces the effect of shortening trail by means of steering geometry changes. Thus, the steering is not noticeably quicker than in previous models. As the bigger front tire is heavier and tends therefore to resist deflection to a greater degree, the “quickening” effect of any trail reduction will also be diminished.

If you are used to the self-aligning effect of a smaller front tire in cornering, the new one, which leaves more up to the rider, takes some getting used to. Once you do. you'll find that the Commando sticks well, corners beautifully, and, like its predecessors, should establish among the purists that eyeballrolling reverence so common to passionate Manx and Dommie fans. Aiding the rider who indulges in daring angles of inclination, the mellow-sounding and legal 88 db straightthrough glasspack mufflers have been tilted up slightly from the horizontal. This will obviate grounding in turns, although a somewhat loosely sprung center stand will flop down and make alarming sounds before you get the mufflers even close to the ground. Having reported this to the distributor, we were informed that a stronger spring is being fitted to keep the stand “up tight.”

MADE FOR THE HIGHWAY

If you are primarily an around-town, under 50-mph sort of rider, you will not derive the fullest possible appreciation of this motorcycle, although it maneuvers through traffic with a fair amount of ease for its size. It is a high-speed sporting machine, and needs lots of open winding road and freeway to unfold its true nature. It accelerates to 80 or 100 mph in great, smooth, animal-like rushes, and you may ignore the gearbox entirely in most passing situations above 55 mph.

As such is the case, it is hardly fair to call the Norton’s powerplant old-fashioned. If it does the job, it does the job, and that should be the criterion for most people. The Commando can stay with any of the other so-called Superbikes, even speaking only in terms of sheer acceleration. The sole objection to making a 750-cc engine in parallel Twin configuration is that it can be quite a shaker, due to primary imbalances produced at the crankshaft by the reciprocation of large pistons and beefy connecting rods.

By isolating the engine in those rubber bushes, it can jiggle to its heart’s content, yet leave the rider unshaken enough to

enjoy the engine’s virtues—torque and flexibility.

The Commando’s engine is a long-stroked wonder (bore 73mm, stroke 89mm) in this day of square and oversquare bore/stroke configurations. Fortunately, it reaches its power peak at about 7000 rpm, which converts to a piston speed of 4100 feet per minute. Piston speed is a rather loose factor upon which engineers try to predict the stress to which an engine is being subjected, and how long it will wear. A figure of 4000 fpm has been considered, in the past, the upper limit of reliability. Lately, this old rule of thumb has risen, due to the improved quality of modern engine materials. Beyond that, one must consider the normal operating range of the Commando, which is far lower than 4100 fpm.

As the engine has a broad powerband and achieves most of its horsepower before the rpm limit is reached, it will be operated at lower rpm and therefore be subjected to less stress than the peak piston speed would first lead you to believe.

REFINING THE GEARBOX

Some improvements have been made in the gearbox this year in the interest of greater reliability. First, second and third gears are now made of a slightly harder grade of steel, “EN 39” instead of “EN 34.” All the shoulders of the mainshaft and layshaft are radiused for increased strength. Due to the machine’s newness, the selection of second gear offered light resistance but soon began working itself out. The internal ratios are ideal, with no large jumps between gears.

It is an interesting curiosity to note that the Commando, when delivered in Europe, has a countershaft sprocket two teeth higher than the American models. All this has to do with national character, we Yanks being oriented to blinding acceleration while the purists overseas think that top speed is

where it’s at. As a result, the Commando for the U.S. will easily red-line in top gear, and has the power needed to pull a higher gear at a faster top speed.

DETAIL CHANGES, AND LUCAS . . .

Several detail changes make the new Commando much easier to live with, notably the rear wheel, which now incorporates a vaned rubber cushioned hub. It smooths the bike's progress at slow speeds and counteracts chain snatch, as well as insures that the drive train will not suffer the ill effects of sudden stresses imposed by rider malfeasances.

The center stand is much easier to use, having been modified with a longer locating lip and mounted on the engine plates in such a position that even a 98-lb. weakling can cope with it. The sidestand is longer, and is more secure on soft surfaces, as it has more support area. Another minor change, a straight-ended chain guard, makes it possible to remove the rear wheel without having to dismantle the chain guard at the same time. The oil tank, located under the snap-off seat, is larger, with an increase in capacity from 3 to 4 quarts; the filler cap comes with a dip stick for easy checking.

The Commando has new controls for the electrical accessories, which it will have in common with most of the other British brands, as they are made by Lucas. They are rather curious, if the intent of Lucas was to rationalize and modernize the system. The “wingtip” thumb switches are annoying to operate, because of the pointed tips, and the auxiliary buttons that are placed above and below them are too small and indefinite in feel. For this, you cannot blame Norton, as the Lucas company is somewhat of a monopoly in England. The Smith tachometer and speedometer faces are simpler and easier to read for the average rider. The odometer counter was a clinker and quickly went awry, trying to make us believe that it had been around the world three times and back. Too bad that Norton-Villiers has to bear up under these outside annoyances, for which they have no direct responsibility. Otherwise, the machine is a beautifully executed whole.

A SLEEK, LUSH TOURER

The people at Norton-Villiers like to call the Commando their “European” version, their “fastback.” It does have some of the character of a sleek, lush grand touring car. The striking red slash of the integrated fuel tank and fender is nicely offset by the supple black leather saddle, the front of which is lipped to provide knee pads at the rear of the tank. If you are too long-legged, or short-legged, however, they don't provide a perfect match for the position of your knees, leaving you with some indecision about where to sit in the saddle. Or you may find that they make your legs stick out into the airstream.

But this idiosyncrasy is soon forgotten when you fire up that throbbing big Twin. It requires a heavy kick when the engine is cold to overcome the oil drag, but the starting procedure is easy. Use the choke lever and flood the carburetor float bowls generously with the tickler and a few prods will bring it to life. Once warm, the Commando is a first-kick starter.

Ease into first, and there’s no clunking. Away into traffic, out onto the highway, and turn it on. There are absolutely no flat spots in the power curve. Dial it on and you accelerate, with no hesitation.

As you gain rpm, the rubber mounting does its job. The handlebars don’t shake or make your hands tingle.

Happiness is the first fast bend. The Commando is solid, secure, and as easy handling as some 500s. There may be something to “purism” after alk Updated. Commando-style. [O]

NORTON 750 COMMANDO FASTBACK

View Full Issue

View Full Issue