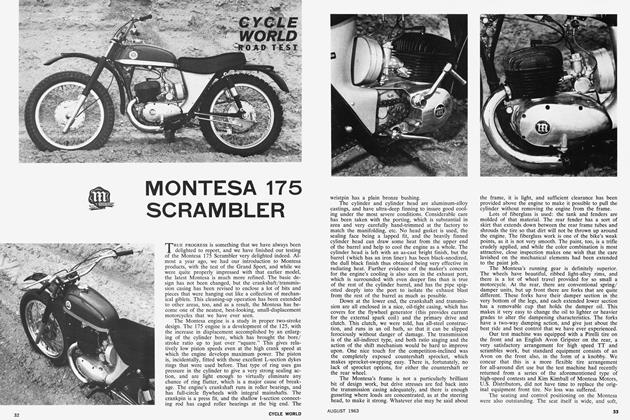

CYCLE WORLD ROAD TEST

Road Test and Technical Review, to be finished on the Daytona oval.

ON OCTOBER 21, 1965, George Roeder climbed into a streamlined Harley-Davidson "Sprint" and zapped back and forth across the Bonneville Salt Flats for a two-way average, over the flying mile, of 176.817 mph. As a record, it was officially recognized only in this country, by the American Motorcycle Association, but regardless of who recognizes what among the weird and wonderful world of motorcycle associations, the Sprint did in fact go faster than any other unsupercharged "250" in the history of motorcycles. And that was with a touring bike-based "pushrod" single-cylinder engine, burning straight gasoline. Really an amazing feat.

The engine used in setting that record more properly belongs in Harley-Davidson's 1966 road racing Sprint, the CR-TT. Although this motorcycle is similar in appearance and general layout to last year's competition Sprint, and to the current Sprint touring machine, it is actually a new design. New engine, new frame, new tank, new seat, new new, new. .

l3ut the most important changes are in tne enginei transmission unit; changes that begin in the cylinder head and continue right on back to the last bit of transmission housing. The cylinder head is a new casting, with a bigger and better intake port, and bigger valves. Actually, the present 39mm (1.535") intake valve has been used in earlier engines, to replace a still earlier, smaller valve, but it is now being used in conjunction with a larger port and a 33mm (1.299") exhaust valve. Last year's engine had a 29mm (1.14") exhaust valve, which was the big gest thing that could comfortably be accommodated in the old, small-bore engine and still leave room for a large enough intake valve. In the new head, the spark plug position has been moved, too, as a result of lengthy experimentation in plug location. Combustion control has become much more a problem with the compression ratio raised to 12.0:1, and work with piston "squish" bands and plug location have been required to avoid detonation.

HARLEY-DAVIDSON SPRINT CR-TT

A change in rocker-arm ratio has necessitated the repositioning of the rocker pivots, but there has been no change in the method of mounting. The rocker shafts are still carried in the head casting; the rocker covers are there for access only. These shafts turn in brass bushings pressed into the sides of the rocker cavities and are retained by end-plates with an oil-feed line leading into the end of the intake rocker shaft. The exhaust rocker is "splash" lubricated by oil draining down from the intake rocker "box" and goes from there to a drain-pipe which returns it to the crankcase.

The reason for changing the rocker ratio is simply that such a change makes life easier for the valve springs. The ratio is 1.59:1, which means that lift at the cam follower is multiplied by 1.59 by the time it gets to the valve. Thus, the followers and pushrods do not move as far, and are not as much bothered by inertia effects. On the other hand, pressure loads on the pushrods and followers will be multiplied by a factor of 1.59. Apparently, Harley-Davidson's engineers feel that the increased resistance to valve float is worth whatever problems may arise from the higher pressures.

A big carburetor has been provided, too. The carburetor is a Dellorto SSI 3OD; a TT-pattern instrument with a 30mm throttle bore. It is mounted vertically and leads straight into a vertical port which, because of the cylinder position is, in effect, actually only slightly downdraft relative to the intake valve. Fuel is fed from a remotemounted float chamber, which has a rubber cushion between the chamber and the frame, and the carburetor itself is isolated from the engine by a rubber (neoprene, probably) sleeve connecting the halves of the two-piece manifold.

We are told that experiments have been made with larger carburetors, but that they gave disappointing results. No perceptible increase in power at maximum revs, and a definite drop lower down on the power range. We might mention that other experiments, involving the long, slow-taper megaphones used on these machines in Europe, showed a drop of about one horsepower at the peak, but spread the range a great deal.

Valve timing, with the "H" camshaft used in this engine, is 73-92, 105-55. That is to say, the intake opens 73° before top center and closes 92° after bottom center. The exhaust opens 105° before bottom center and closes 55° after top center. Duration for the intake is 345°; and 340° for the exhaust. Overlap is a whacking 128°, which places the H-contour camshaft well over on the radical side of things. Lest you think that this timing only appears to be "long," and the result of including long, slow opening ramps, consider first that the timing figures given are measured at 5-7° of lift at the valve.

Maximum power is reached between 9800-10,000 rpm, where the average 1966 CR-TT engine delivers 32 bhp to the transmission output sprocket. This is probably 4-5 bhp more than was being extracted from the old long-stroke engine. Curiously enough, however, even though the bore/stroke dimensions have gone from 66 x 72mm to 72 x 61mm, the new short-stroke engine is being run at nearly the same crank speed as before. You were allowed a "safe" 9500 rpm with the long-stroker; the recommended limit for the short-stroke engine is 10,200 rpm. This means that the new Sprint is running at a much lower stress level than before, and should prove exceptionally reliable.

If the appearance of the crank, rod and piston present a true picture of reliability, this engine will be nearly unbreakable. The connecting rod, especially, has a real "racing-engine" look about it. It is an I-beam forging, with ribs around the piston and crankpin bores for strength. A caged, double-row roller bearing is used at the big-end of the rod, and these rollers run directly against the crankpin and the rod. The full-floating wristpin bears against a bronze bushing in the small-end of the rod.

Racing Sprints in years past could not claim their clutch as being one of their better features. In fact, the old clutches just would not carry the load unless the spring behind the pressure plate was made so strong the rider could barely budge the clutch lever. In the CR-TT that problem has been eliminated. The racing Sprint's clutch has been moved outside the primary-drive housing and completely redesigned. It is now a "dry" clutch, with enough plates to handle engine output without slipping, and placed where it gets plenty of cooling air. The rider can abuse this clutch all he likes and it will not fail. If he slips it enough, the plates will eventually wear out, but he will have no problems with the unexpected. And, control-lever pressure is down to a level not many touring bikes can match. In all, it is a lovely, lovely clutch light as a feather and (after a bit of practice) very controllable.

All things considered, it is a fine thing the clutch is so good, for a combination of an extremely narrow power range and ultra-tall low gear in the close-ratio, 5-speed transmission makes it impossible to get underway without a great lot of clutch-slipping. With "Daytona" overall gearing, low gives a total reduction of only 11.65:1, and one must get the bike churning along at almost 50 mph before the revs climb to 8000 rpm where the effective power band begins. Without a lot of controlled clutchslip, you would be a long time getting the Sprint to move after the flag falls.

There are actually two different gearsets available for this new Sprint CR-TT. The "5A" set has ratios of: 2.076:1, 1.620:1, 1.273:1, 1.084:1, 1.000:1 for first through fifth. "5B" has a 2.26:1 low, 1.75:1 second, 1.37:1 third, 1.12:1 fourth, and the same direct-drive fifth. Our test bike had the ultra-close 5A transmission, being destined for Daytona, where the very-close ratios are of considerable usefulness in getting up to speed around the long, banked oval.

And then there is the new frame. Basically, it is still a single-tube, "backbone" type frame, but redesigned for added rigidity. It is unusual in having a pair of forged steel plates to hold the swing-arm pivot, and these are welded to a cross-piece at the back of the main frame tube and bolt to the engine's crankcase. Additional smalldiameter tubes support the seat and provide mounting points for the rear-suspension units.

There have undoubtedly been changes in steering geometry and overall balance, but there is no specific information available regarding this point. In any case, the bike has what appears to be the same telescopic forks and rear "shocks" as the 1965 Sprint, and yet it handles better. Harley-Davidson says the new chassis has proved to be two seconds per lap faster at Daytona when both old and new chassis were being propelled by the same engine and handled by the same rider.

The brakes remain the same as before. The Sprint CR-TT is fitted with 200mm (7.9") Oldani brakes, the front drum having double-leading shoes; the rear brake has one shoe leading and the other trailing. In the 1966 brakes, the front brake shoes have what appears to be Ferodo "Green-Stuff" linings. This lining material has super-friction characteristics, and it makes the new Sprint stop like nothing else in the production-racer class. In fact, the brakes are almost too good. The rider must use care with the front brake, for it is astonishingly easy to actually lock the front wheel.

In common with many modern motorcycles, last year's Sprint CR had an "energy-transfer" type ignition system, with the sparks originating over on one side of the engine, at the crankshaft, and the breaker points at the opposite side, on the end of the camshaft. This arrangement can work well, but it is all too possible to get the generating source and the points out of phase, which means that the sparks weaken or disappear. In the CR-TT they have hit upon a better system, mounting a small magneto right on the end of the camshaft. There, it is easy to time, and keep in time, and as it runs at half engine speed, it delivers its strongest spark when the crank is spinning at 9000-10,000 rpm, right up there where it is needed.

Racing motorcycles are seldom as well finished as the Harley-Davidson CR-TT. Its engine/transmission case castings are left as-cast, but they are smooth and attractive for all that. Very businesslike. The fiberglass tank, seat and front fender are very well done, and have their racing-red color bonded right in.

The only complaints we have are directed at the control levers, which are too straight for comfort, and the footpegs, these being of such an unhandy diameter that they make it difficult, at times, to get one's right toe under the gear-change lever for downshifts. Of course, a bona fide Harley-Davidson rider would not notice anything the least bit unusual about them, as pegs of a like diameter are used on all the Milwaukee Marvels not actually fitted with foot-boards. Also, large riders will find the Sprint CR-TT a trifle cramped, but this is not much of a problem; it is a simple matter to drill new mounting holes and shift the seat back for more room.

One item not often fitted as standard equipment on road racing bikes is a "kill" button. Presumably, this has been provided to give the rider the option of making full-throttle, clutchless shifts. We tried it, and it works fine. The Sprint has one of the smoothest, most positive gear-change mechanisms we have ever encountered, and the lever moves (as the sporty-car types used to be fond of saying) "just like it's slicing butter." To make a killbutton shift, you put a bit of pressure on the pedal, and then simply pip the button quickly as the tachometer sweeps up to 10,000 rpm. There is no jerk, no clank; nothing but a change in engine note as the revs drop with the change in ratios. It goes without saying that this technique is only used for upshifts. Coming down through the gears, you use the clutch.

Those not in a great, thundering hurry may want to use the clutch for upshifts as well, as it is surely more kind to the transmission than the kill-button. However, there is an excellent chance that you will get away with the kill-button shifts for a long time. The 1966 Sprint CR-TT has had its gear widths increased by 25%, and has larger shafts and higher load-capacity bearings.

Good handling is a vitally important factor in a road racing motorcycle, and the Harley-Davidson Sprint CR-TT has it. The bike is steady in fast turns, and extremely agile around the slow stuff. Its most outstanding handling characteristic is quickness; all the rider has to do is think about turning, and the bike pops right over and starts carving its way around a corner. No effort is required; no pulling at the bars and hitching one's body over the side to get the "peel-off" started. In part, this is probably due to the Sprint's low center of gravity, but the rather shallow fork angle must also contribute to the quickness of the steering.

We tried the bike at the tight, bumpy Carlsbad Raceway course, and at the fast, bumpy Willow Springs, and it behaved very well in both places. A bit stiffly suspended at the rear for Willow Springs; those ripples in 100-mph bends make the rear wheel step-out if the rider is really "scratching" as the British say. But this was amply compensated by its behavior at Carlsbad, for it did not have the fork-twitch most motorcycles develop when clearing "Vesco's Leap" flat-out in top gear.

At this point in our testing, we usually get on with the performance runs. In this instance, the performance phase will be conducted at the AMA's Daytona races, where the Tech. Ed. will ride this very Sprint in the Amateur/Expert 100-mile event for 250s. When all is said and done, the only true measure of the Sprint's performance is its ability to equal, or exceed, the performance of the other 250cc-class road racing motorcycles. We can give you an idea of the Sprint's general performance: geared for the quarter-mile, it will get to just over 100 mph at the timing trap, albeit with no startling elapsedtime figure due to the inconveniently (in this instance) tall first gear; with Daytona gearing, the top speed will be around 130 mph.

One point that should be made is that the less-thanexpert customer will find the 1966 CR-TT a real handful to ride. The power-band is very narrow, and the rider will find himself pumping the bike along with the gearchange lever. It will be a good thing to keep an eye on the tachometer, too, for the engine continues to pull very strongly right past the red-line and into the range of valve-float (at about 11,000 rpm). This can happen before the rider knows it is happening when the bike is carrying short-course gearing. And, at the other end of the scale, if the rider lets the revs drop too much in a turn, he will find that he is obliged to make a downshift right then and there. When this engine drops "off the cam," it drops with a thud, and the fellow behind will if he is trying at all zip past before you can blink your eyes.

As a matter of fact (and here is where we make ourselves especially popular in Milwaukee) our advice to Harley-Davidson would be to offer a "short-course" CR-TT with the 5B transmission ratios and a long, "European" exhaust system. It would be much easier for the novice to live with, and even the experts might find that a Sprint set up in that manner had its advantages on a short, twisty circuit. However, with either transmission or megaphone, the Sprint CR-TT is sure to become a most popular mount for the hotly-contested 250-class races. It is fast, and handles well, and has the best brakes of any 250 we have tried. And, we have some inside information that tells us it is also phenomenally reliable unless overrevved. The 1966 racing season should be very, very interesting.

HARLEYDAVIDSON SPRINT CR-TT

$ 1,000