AN ERA OF RACING HONDAS

Is It Really Over Or Is There Something New Just Around The Corner?

RICHARD C. RENSTROM

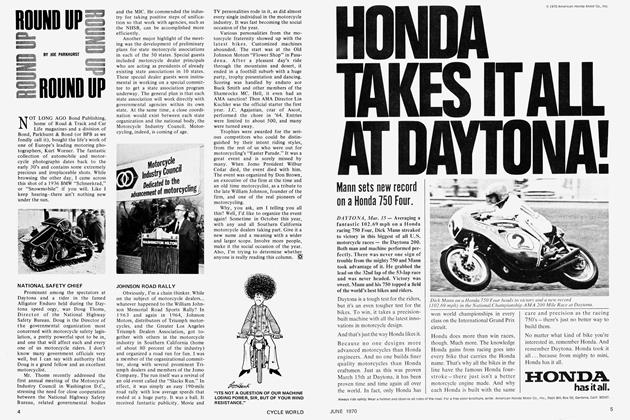

HONDA'S ONE-SHOT entry and win at this year's Daytona classic brings to mind one of the most remarkable stories in motorcycling. Soichiro Honda is legend, a genius who put the Japanese on the international motorcycling map.

Prior to the middle 1950s, Japan was an absolute nothing in motorcycle production, with only a few small companies producing a handful of archaic models that looked like something produced in Germany way back in the early 1930s. This all changed after Honda started rolling on two wheels, though, and by the early 1960s his machines were as good as anything in the world— as well as becoming undisputed sales leaders.

This rags to riches story of Soichiro Honda is a remarkable tale, but to many the history of his motorcycle production is far overshadowed by his success in international grand prix road racing.

This is especially true for the more sporting and technically minded types, who have, in the works racing Hondas, the very summit of four-stroke technical excellence. These Hondas, in the hands of some of the greatest riders the world has ever seen, have amassed a tremendous record in their nine years of racing—18 world championships and 137 classic victories. When Honda pulled out of international road racing at the end of the 1967 season, its fabulous multi-cylindered works racers were considered to be the most highly developed four-stroke models in the world, and so far nothing else has come along to take their place.

The story of Honda racing excellence began in 1954 when Soichiro visited the Isle of Man to study European racing design as well as to lay the groundwork for a visit by some of his racers the following year. Two weeks later, Soichiro returned to Japan—half in shock and half in despair. Honda had discovered that the European bikes developed three times as much pressure as his engineers could raise, and the technical excellence of the fast European bikes was devastating to his Oriental pride.

Returning home, Soichiro turned his talents to improving the production models—as well as developing some racing models for the Japanese racing events. By 1959 he felt that he was ready to challenge the European giants, so off went a team to the famous Isle of Man TT races.

Honda’s team that year consisted of four Japanese riders plus American Bill Hunt, who acted as rider and manager for the equipe. The riders were all mounted on 125-cc Twins, which had a very roughshod look about them. The Twin had a bore and stroke of 44 and 41 mm, and the lower end featured roller bearings throughout. The valves were actuated by double overhead camshafts, which were driven by bevel gears and a vertical shaft. Carburetion was by two Keihin units, and the ignition was by a magneto.

The real point of interest in this tiny Twin was the use of four valves per cylinder—a practice that had been scorned by the Europeans since the “pushrod” Rudges that dominated the 1930 Junior and Senior TT races. The power output claimed by Honda was 18.5 bhp at 14,000 rpm, but their subsequent performance in the race itself seemed to suggest that this was an optimistic claim.

This first racing Honda had a sixspeed gearbox, with the primary drive by gear. The rather large engine-gearbox unit was housed in a tubular spine frame with a swinging-arm rear suspension, and the engine acted as a part of the main frame section. The front fork was really wild, though—a cumbersome leading-link mechanism that mated to a huge front hub with a 180-mm double leading shoe brake. The tire sizes were 2.50-19 front and 2.75-18 rear.

In the 125-cc TT race the screeching 176-lb. Twins proved to be very reliable, with the four Japanese riders finishing in 6th, 7th, 8th, and 11th positions. Hunt crashed and retired, but the team still managed to win the team prize. Flat-out speed was nowhere near that of the MV Agusta, Ducati, or MZ models, and handling was obviously not first class. But Honda had gained his first point in world championship racingone point for 6th—and he returned to Japan with his head full of European ideas.

Little did the racing world realize at this time that here was a force with which to be reckoned, one that would completely change the complexion of international road racing within a few short years.

The next significant step in this story occurred late in 1959 when Honda showed up at the Asama Circuit with a new 250-cc Four that had the same bore and stroke as the 125-cc Twin. Its engine was set vertical in the frame (compared to a slightly inclined position on the Twin), and the camshaft drive was taken off the right side instead of the left side as on the Twin. The ignition was also changed to battery and coils, and each cylinder had its own carburetor.

This engine was claimed to pump out 35 bhp at 14,000 rpm on a 10.5:1 compression ratio, which should have given it fierce performance. As Japanese road races were then held on dirt roads, this exotic looking model was fitted with semi-knobby tires! The Four was highly successful in the local Nipponese races, and then all of them were supposedly put to the sledgehammer at the end of the season.

During the long winter season the factory engineers were put to the task of designing some new 125and 250-cc road racers that would be competitive in Europe. The idea behind this move was to gain worldwide fame and thus increase sales, which is a route that many a small factory has taken in order to become established. To this end the small Honda Company dedicated itself.

Honda’s next appearance was in the 1960 TT races, which traditionally started the European racing season in those days. By then Honda had come to

realize that he could never win in Europe without some experienced grand prix riders, so he hired Australian aces Bob Brown (ex-Gilera rider) and Tom Phillis for the TT races. Jim Redman of Rhodesia also joined the team after the TT, so Honda had a formidable trio to lead their challenge in classical roa< racing.

The big topic was not these riders, though, but rather the new 125and 250-cc models that graced the starting grid. The two models were still a Twin and a Four with the same bore and stroke as before, but that was about the only similarity between the 1960 racers and the previous Honda GP models.

Perhaps the biggest difference was in the engine, where a central gear drive was used to drive the two camshafts. The four-valve principle was retained; although it was still shunned by European designers, the basic principle was most sound, and in the end the scoffers were destined to come over to Honda’s theory.

To effect this four-valve arrangement, Honda used two lobes on each camshaft per cylinder, with the cams bearing directly onto inverted cups that fit over the duplex coil valve springs. The advantage of this four-valve setup is not so much in increased performance but rather for the purpose of reliability. At engine speeds of 14,000 rpm or higher, the valves can easily lose contact with the cams, which is a phenomenon called valve float. When valve float occurs, the whole valve train is under a greater shock load and thus more susceptible to failure. The other valve float danger is in the valves touching the piston or one another.

Total weight of a valve, spring, collar, and cup on the 250-cc Four was only 20 grams, and the factory said this allowed the engine to be buzzed some 3000 revs past the 14,000 rpm power peak speed with no ill effects upon the engine. This low reciprocating weight of the valve gear was a unique feature of the 1960 Hondas, and it is also one of the truly great milestones in the engineering history of grand prix motorcycles.

Some of the remaining Honda racers had some orthodox, and others not so orthodox, features. The alloy crankcases were split horizontally, which was the opposite of European practice, but the roller bearing lower end was standard procedure. The crankcase contained the oil sump, though, whereas the Europeans still preferred a separate oil tank. Honda also used cast-iron skulls in the alloy heads to form the combustion chamber, whereas the Europeans favored a straight alloy head with valve seat inserts. The ignition was by battery and coil, and it was possible (due to the four-valve setup) to mount the 10-mm spark plug directly on top of the combustion chamber. The compression ratio was 10.0:1.

These new engines had a much greater power output, with the 125-cc Twin developing 25 bhp at 13,000 rpm for a speed of about 112 mph, while the 250 pumped out 45 bhp at 14,000 revs for a 137 mph speed. Acceleration, through a six-speed gearbox, was very good. Only a racing shakedown would prove how good the reliability was.

Handling was also notably improved, with a new “space” frame that employed the engine as a frame section plus an orthodox telescopic front fork. The hubs were also new with single leading shoe brakes both front and rear. The tire sizes were 2.75-18 front and 3.00-18 rear. The fuel tank was a long and lean looking thing that came in five sizes from two up to eight gallons. A dolphin type fairing provided good air penetration.

These bikes were very new, and needed a great deal of proving—exhaust systems, carburetion, gear ratios, ignition, handling, etc.—before they could become winners. Despite this, the team did very well, with Bob Brown heading a Honda trio that took 4th, 5th, and 6th in the Lightweight TT and with Naomi Tanaguchi finishing 6th in the 125-cc event. Honda also contested the grand prix series, and in the Dutch GP a 6th in the 125-cc class was obtained. The Hondas all failed to finish the fast Belgian event, but in the German they garnered 3rd and 6th places with the

Four. In the Ulster classic the Fours finished 2nd, 3rd, and 5th; and at Monza the Fours took 2nd, 4th, 5th, and 6th, while the Twins bagged 4th and 6th places. Jim Redman was the most consistent rider, and he finished the 250-cc title chase in 4th position. The season’s verdict was—reliability fair, handling satisfactory, and speed only a tiny bit less than the fastest of the fast.

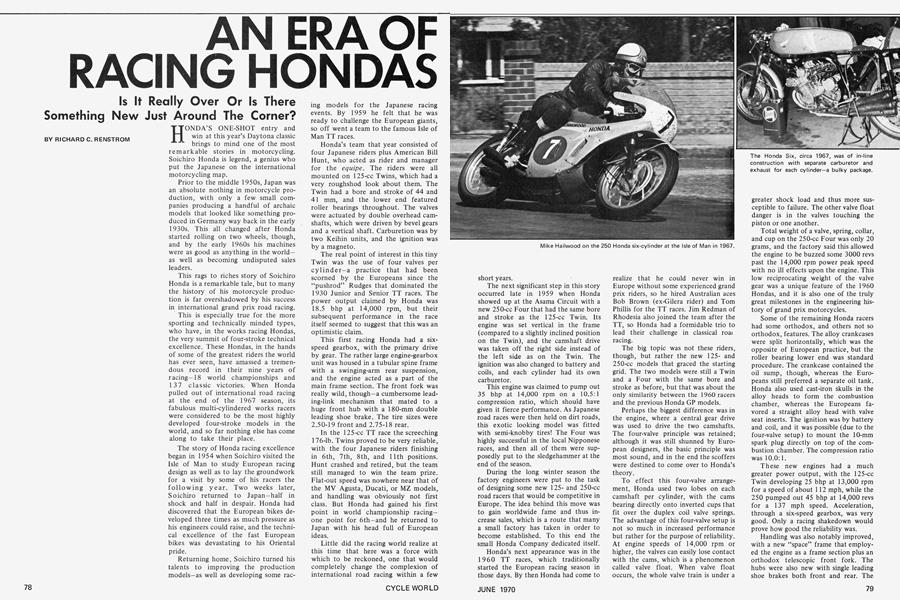

During the off season Soichiro’s technicians made many small changes in the bikes to make them more rehable as well as faster. Honda also made a determined effort to hire the finest riders in the world, with such greats as Luigi Taveri, Mike Hailwood, and Bob McIntyre joining the team. These riders, plus Redman and Phillis, gave Honda a formidable team, and money was poured into grand prix racing as never before.

The season began that year with the Spanish GP at Barcelona, and Tom Phillis gave Honda his first grand prix victory when he trounced the field on his tiny Twin. Try as he might Phillis could not edge out Gary Hocking’s MV Twin in the 250-cc race. Gaining momentum, the team went on to the TT races where Hailwood won both the 125and 250-cc events at record speeds. In the larger event, Bob McIntyre racked up his. fantastic 99.58 mph lap record from a standing start. In the end, Hailwood won the 250-cc World Championship and Phillis garnered the 125-cc title. Honda won every 250-cc class race after the Spanish event, but in the 125,-cc class the fast MZ two-stroke was only narrowly defeated.

In 1962 MV lost heart and pulled out of the 250-cc class, so that Jim Redman had no opposition worth mentioning. Luigi Taveri also won the 125-cc title, but the 50-cc Honda Single was slaughtered by the Kreidler and Suzuki twostrokes in the new tiddler class. This 50-cc thumper pumped out 9.5 bhp at

14.000 rpm, but it just wasn’t fast enough to hold off the screeching rotary-valve two-strokes.

Big news that year was Jim Redman’s 350-cc world title, won by using a 285-cc Four that developed 50 bhp at

14.000 rpm. Jim had a full-fledged 350 for the Ulster GP, though, which had a bore and stroke of 49 by 45 mm. After a year’s development, this Junior class model was producing 56 bhp at 12,500 rpm, giving it a top speed of 156 mph.

In 1963 Honda reduced their racing budget, which meant the death of the 50-cc Single. Redman retained his 250 and 350 championships, but Suzuki’s new 125-cc two-stroke Twins were much too fast for the Honda Twin. Even in the lightweight class Redman’s title was not a sure thing, since Jim had to defeat Tarquinio Provini’s embarrassingly fast Moto Morini Single in the final event of the season in Japan to claim the title.

In 1964 Honda recognized that complacency had nearly ruined them in the racing game, since design progress was then moving ever so swiftly. Responding to these new challenges, Honda introduced a 125-cc Four that had an eightspeed gearbox and revved to a fantastic 16,000 rpm. This four banger proved to be a superb little racing bike, and Taveri succeeded in regaining the title for Honda.

The 250 was also improved, with 48 bhp being wrung from its reliable “old” engine. This provided a speed of 145 mph, but the 150-mph Yamaha Twins were just a wee bit faster and Honda thus lost their championship. Honda fought back gamely, though, and Redman wheeled out a spanking new sixcylinder model for the Italian GP. This new Six was a real flyer, but ignition trouble prevented the Rhodesian ace from battling with the Yamahas.

The following year Honda re-entered the tiddler class with a 50-cc Twin, and it surprised all by winning the world championship in the hands of Ralph Bryans. In the 125 and 250 classes the Suzuki and Yamaha two-stroke Twins were just too fast, and Redman and Taveri were both soundly trounced. Actually, the 250 Six was a very fast bicycle, but reliability was only fair. This is a normal situation with most new designs, so great things were expected of Honda in 1966.

During the off season Honda worked feverishly on their raceware and signed Mike Hailwood to the team. Obtaining Hailwood made the Honda prospects look exceptionally bright, since the Englishman was considered at that time to be the finest rider going.

In anticipation of the Honda challenge Yamaha fielded a new 250-cc water-cooled V-4 model that was rumored to develop 65 bhp. This proved to be an optimum situation for Honda, however, since they had spent over one year in getting the bugs worked out of their 250-cc Six. The Yamaha, meanwhile, was totally new for 1966, so that they would be spending the year in getting the reliability and handling problems worked out on their two-stroke.

And so it went, with Hailwood winning the 250 title on his Six over a fast but not too reliable Yamaha V-4. The two-stroke also did not handle very well, and Mike was just the man to exploit all of these advantages in every corner. Hailwood also won the 350-cc crown on his bigger Four, but Giacomo Agostini had been a fierce competitor on his new MV Agusta Three. The MV did not have anywhere near as much power as the Honda, but the lighter and slimmer three banger out-handled the bulky Honda so that the Italian very nearly made up in the corners what he was losing on the straights.

The 125-cc title also went to Honda, with Luigi Taveri barely nudging out Bill Ivy’s 40-bhp Yamaha. The small Honda was a real surprise, for it was a five-cylinder model—perhaps the only Five that has ever been built. It developed a fantastic 36 snarling horsepower at around 19,000 to 20,000 rpm. This high revving Five was known as being temperamental. Minor changes in atmospheric condition could make it necessary for lengthy tuning sessions to keep it running well. The power band was very narrow—only several thousand revs—and the riders complained that the Five was a difficult bike to ride. An eight-speed gearbox was really needed on this model, and Taveri was the only one who ever really mastered it.

The tiny 12-bhp 50-cc Twin did not fare too well against the 17.5-bhp Suzuki three-cylinder two-stroke, and Taveri and Bryans had to be content with the runner-up positions. By then there was talk of dropping the tiddler class, so perhaps Honda did not wish to invest in the development of a new engine.

Probably the biggest news in 1966 was the new 500-cc Four, which had been promised to Hailwood if he would just sign on with Honda. The big 30incher was a beastly looking thing, and everybody expected it literally to devour the “old” MV Agusta Four. MV, however, came out with their now famous 420-cc Three, which was supposed to develop 65 bhp. The Honda obviously would have more horsepower, and with both Hailwood and Redman on board there would be nothing to stop them from sweeping the awards.

The beastly 500 got off to a good start with Redman edging out Agostini in the West German and Dutch classics. Then Jim fell off in the fast Belgian event and broke his arm. That left Hailwood to battle with the dashing young Italian and his fine handling Three. Mike was way behind on points by then, so he really thrashed his massive Four around the circuits.

Several lap and race records fell to the big Honda but so did a lot of broken gearboxes and engines. The problem was the fierce horsepower. Mike had to use the gearbox and engine compression to get hauled up in time. The season ended with Ago on top and Honda’s reputation a bit tarnished.

When the spring of 1967 rolled around all of the “experts” predicted that Honda was not going to take this defeat lightly. The pundits, however, were wrong, for Honda’s all-out efforts in grand prix car racing were draining away both the finances and technical talent that were needed for the bike racing activities.

Hailwood and a few others knew this in 1966, but the public did not know it until the spring of 1967 when Soichiro announced that they were pulling out of 50and 125-cc class racing. The team was then reduced to only Hailwood and Ralph Bryans, plus chief mechanic Nobby Clark.

Honda did introduce one new model for the season, though, and this was the fine 297-cc Six for use against the 350-cc MV Three. This new model actually weighed less than the older Four, and it punched out a wicked 70 bhp. The 297-cc model proved to have an exceptionally good combination of power, weight, handling, and reliability; and Hailwood gave MV Agusta a thorough trouncing. Mike rated this Six as the best all-around racing bike he ever rode. With it, he pushed the IOM Junior TT lap record up to 107.73 mph-only one mile per hour below his best on the big 500.

In the 250-cc class Hailwood and Phil Read (Yamaha) battled all season long-four-stroke Six versus two-stroke V-4. The Yamaha was chucking out a phenomenal 72 bhp which propelled it to 160 mph, but the 66-bhp Honda handled much better and seemed slightly more reliable. Both bikes came apart on too many occasions, however, reflecting the cost of obtaining the very ultimate in performance. In the end Mike and Phil both had 50 points, but the Honda ace got the title due to the FIM rule that gives it to the man with the greater number of first place finishes.

The real donnybrook in 1967 was in the 500-cc class, where Agostini had a full 500 to pit against the super-powerful Honda Four. Once again the more reliable and better handling MV edged out the faster Honda, although it once again took the final event of the season to decide the title.

During the 1967 season Hailwood had lived a nightmarish life with the big Honda, which handled so badly that photographers were known to scurry up the bank as it passed! Mike even went so far as to have Ken Sprayson at Reynolds build him a better frame, but the Honda brass put the dampers to that idea. Despite repeated pleas for a better frame and brakes, Honda mounted Hailwood on an inferior handling beast and chose, instead, to pour money into a GP car that ex-motorcycle champ John Surtees was blowing up quite regularly. The traditional meticulous machine preparation was also lacking, and Nobby Clark complained that his pile of spare parts, engines, and gearboxes had dwindled to nothing.

The biggest of Hondas did have a fantastic performance, though, which has caused a lot of speculation on just how much horsepower it really did have. This was never really known due to Honda’s secretive policy on its racing wares, and perhaps we shall never really know. Nobby Clark, writing in one of the European magazines, has stated that the 500 put out 114 bhp at 12,650 rpm, but that Mike’s bike was “detuned” to 105 bhp in an effort to get things under control.

Clark, however, goes on to say that Hailwood never did believe the claims of 114 bhp or even 105 bhp and, quite frankly, neither do I. In order to get that much power from the 500 Four, Honda would have had to have better volumetric efficiency than it obtained from the 250-cc Four while going to much larger cylinders. Even assuming that Honda could have retained the same volumetric efficiency on its 500 Four as it had on its 350 Four, this would give only 80 bhp. There was, of course, more knowledge gained about engine breathing during their last few years of racing, so that perhaps an 80 to 85 bhp output would not seem unreasonable.

This estimate is further verified by our research into flat-out speeds recorded on the faster circuits, which usually showed Hailwood to be traveling only about five miles per hour faster than the 70-bhp MV Agusta Three. The best information we could find revealed that the fastest speed ever recorded on the big Four was 172 mph on the extremely fast Masta Straight in the Belgian Grand Prix. This is below the 178 mph clocking of the fully streamlined 80-bhp Moto Guzzi V-8 in 1957, still considered by many to be the fastest road racing bike ever built.

MV claimed only 70 bhp and a 165 mph top end for their 500 Three, and Hailwood never really did devour Agostini on even the fastest of circuits. Surely, on a course as fast as the Belgian GP horsepower would tell, yet Agostini blew off Hailwood badly in 1967 and pegged in a lap record of 128.58 mph to boot.

It is also interesting to note that Agostini won on the “horsepower” courses of Hockenheim (112.34 mph), the Belgian (123.95 mph), the East German (105.99 mph), and at Monza (124.42 mph), whereas Hailwood trounced the MV ace on the slower and tighter circuits such as the Dutch (90.84 mph), Czechoslovakian (98.43 mph), and Canadian (80.03 mph). It would seem that a 105-bhp bike with a rider as brilliant as Hailwood on board would have simply annihilated a 70-bhp MV on these faster courses, yet the opposite is what actually happened. It appears to me that Honda had lost heart in bike racing by then, and tried to cover up its sloppy machine preparation and poor team support with a touch of propaganda. The approach, obviously, did not work very well—as proven two years in a row by Agostini and his “underdog” Three.

So the saga of the fabulous Honda grand prix bikes drew to a close. In the spring of 1968 came the announcement that they were withdrawing from active participation in international motorcycle racing. It was not exactly a shock, since it had been rumored for some time in knowledgeable racing circles. But the move took a great deal of interest out of grand prix road racing, since the Honda had been the only four-stroke that had any chance at defeating the screeching 50to 250-cc two-strokes. These great battles in the lightweight classes are now recognized as classics, and the fantastic battles between Hailwood and Agostini also have become epic in proportion.

Will Honda ever return? Perhaps it doesn’t need to, for it achieved what it wanted. It established an unforgettable racing image and its position as a builder of quality products. To this Honda adds its world leadership in sales. So those impeccably prepared machines, swarming teams of technicians, and squads of fine riders might be things of the past.

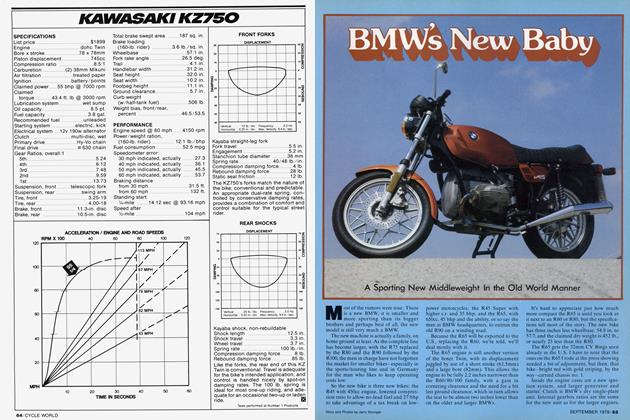

Yet the lure of racing is strong. Commercially, Honda had no reason to go to Daytona this year. But they did, with highly refined versions of the production 750-cc Four. And they won.

They are coy about future attempts on the AMA circuit, which is fast becoming more competitive than the GP contests in Europe. But that victory at Daytona may tantalize them to further racing efforts. If it happens, one of the most exciting eras in American road racing may be just around the corner...

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsRound Up

JUNE 1970 By Joe Parkhurst -

Legislation Forum

Legislation ForumIllinois Success Story

JUNE 1970 By Lee Strobel -

Departments

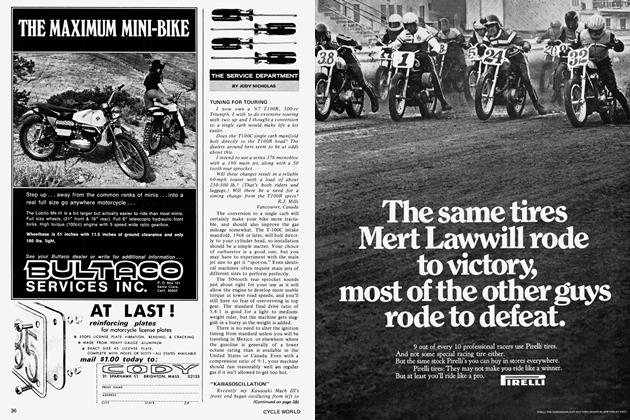

DepartmentsThe Service Department

JUNE 1970 By Jody Nicholas -

Departments

DepartmentsThe Scene

JUNE 1970 By Ivan J. Wagar -

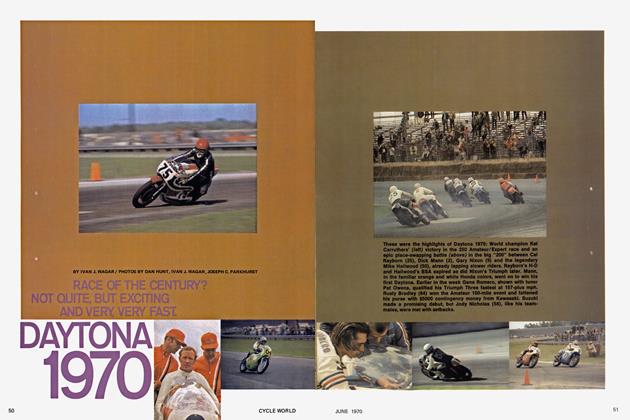

Special Competition Feature

Special Competition FeatureDaytona 1970

JUNE 1970 By Ivan J. Wagar -

Features

FeaturesOverland Adventure

JUNE 1970 By Dean Haagenson