MONTESA 250/5 CAPPRA

CYCLE WORLD ROAD TEST

When Is A Motocrosser Not A Motocrosser?

MONTESA'S CONCEPTION of a scrambler is of the Spanish school, i.e., it is not particularly specialized for any one branch of the dirt riding sport.

You can call the Cappra a motocrosser, but it is not completely that. For, by rigging it slightly differently, it may also be made to perform competitively in the desert, at a TT scrambles, or even at a professional steeplechase event. As such, it is a particularly useful racer for the American rider—who may choose to alternate the types of events in which he competes. Motocross is catching on like Gangbusters in the U.S., but there still remains a predominately larger number of smooth track events for the weekend Sportsman slide artist.

To prove this point, we went to opposite extremes, sampling a motocross style Cappra in the boonies and then running a “Class C” style Cappra in the more artificial confines of Ascot Park. The former situation demands stability in the rough and a flexible engine. The latter demands a low eg slider, and puts the Cappra’s five-speed gearbox to good use.

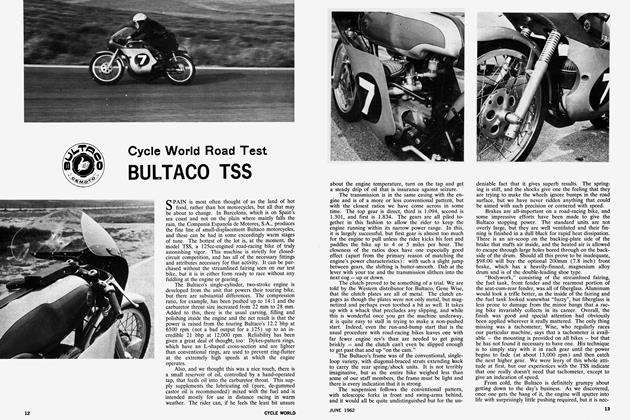

Eye catching appearance is the highlight of the machine. Bright orange fiberglass gas tank, side panels, and fenders, set off a white enamel frame. Engine cases, wheel rims, hubs and fork legs are polished aluminum, while chrome is used for the rest of the hardware. The black vinyl covered seat is nicely styled, and comfortable as well. The Cappra’s finish is quite acceptable, and shows a marked improvement over the first examples exported to this country by the Spanish.

If beauty were the criterion for judging competition motorcycles, Montesa’s 250 would be in the same league as Miss America. Unfortunately this is not the case, as beauty contests and racing events bare little resemblance.

A conventionally ported, 247-cc, two-stroke Single provides ample power for the Cappra. Ball bearings pressed into aluminum cases support the crankshaft assembly. Rollers are used at the crankpin, while the small end of the connecting rod rides on 28 uncaged needle bearings. Dykes type rings are fitted to the piston, which runs in an iron lined aluminum cylinder.

The cylinder barrel is held to the crankcase by two short alien head screws and four long studs which pass up through the head. A special long tool is necessary to remove the alien screws, which are located at the bottom of vertical holes bored in the outer portion of the cylinder. At the top of the holes is a pair of threaded studs, which help to hold the head on. These studs must be removed before the tool can be inserted into the holes to remove the alien screws. You could say a great many nasty things about these immovable cylinders, until you found the hidden screws.

The exhaust system is held to the cylinder by a threaded ring which screws directly into the outer exhuast port opening. This method is quite effective for conducting heat away from the cylinder and into the exhaust pipe, but has one drawback. This type of mounting allows the expansion chamber to move, and the engine unit vibrates, causing a constant point of stress where the threads of the steel ring meet the aluminum of the cylinder. A much better solution would be to bolt an adapter directly to the cylinder, slip the end of the exhaust pipe into this adapter, and connect the two by springs. This latter mounting method would prevent the exhaust flange ring from constantly coming loose, and causing eventual failure of the aluminum threads in the cylinder.

A constant mesh five-speed transmission, shifting on the right, replaces the old four-speed, and is coupled to the engine via an all metal plate clutch and gear drive primary. It worked flawlessly, with our favorite down for low and up for the rest shifting pattern. Ratios are close, allowing optimum use of the

powerband at any speed. The clutch seemed to slip slightly when kick starting a cold engine. This minor malfunction would disappear once things got warm, and never was noticeable when shifting or once the machine was underway. The effective kick lever engaging arc is a bit short for the rotation required to bring the engine to life. Fortunately the flywheel magneto gives a hot spark at a very slow engine speed, and starting drill is kept to a minimum of three or four quick kicks.

The frame is made of mild steel tubing, and has a single down tube running under the engine unit. A pair of smaller diameter tubes form a triangle on each side, by connecting the top backbone tube with the swinging arm pivot area. Swinging arm pivot bushes are steel sleeves bonded to rubber. When new these bushings are fairly rigid, but after a few miles in the dirt they become quite pliable, and the feeling is like the rear tire has gone flat. After Montesa has spent so much effort in trying to make the swinging arm pivot area rigid, it seems a waste of time to mount the arm in rubber. Bronze bushings that can be lubricated from the outside would be an ideal solution, and would give a much more stable feeling.

The front forks are Montesa’s own design, with aluminum legs fitted to chromed steel shafts. Compression and rebound damping are first rate, with enough travel to soak up the roughest ground. The rear dampers have chrome springs, with the top half covered to keep grit off the inner shafts. Full width aluminum hubs have high tensile strength alloy rims spoked to them, with Pirelli Motocross pattern knobbies providing the bite.

Braking is good, in fact too good. When riding on dirt, traction is not always ideal. In this situation the brakes have to be predictable, so as not to easily lock the wheel. The Cappra’s brakes would be better fitted to a roadster, for the extra weight and braking power unnecessary on a machine designed for dirt use.

The rear hub incorporates a rubber shock absorbing unit to protect the transmission and primary drive gears from the jolts encountered in shifting and bouncing over rough country. It’s a welcome addition, as most American riders have little regard for the lifespan of their machine’s internal pieces.

The Cappra 250/5 is more at home bouncing across the desert than trying to stop and start out of the tight, bumpy turns of a motocross circuit. The 250’s long wheelbase and steering geometry make it an ideal cross-country machine. The engine has gobs of torque, and is very responsive and easy to control. Handlebar and footpeg positions are well suited to a sit-down style of riding, making 100-mile events more comfortable. The most amazing thing about this motorcycle is its versatility, for Montesa 250 riders have scored wins in the desert and TT events on the same machine.

Having ridden the 250/5 Cappra in the rough, we jumped at the chance to try a differently rigged version on a professional TT track. Kim Kimball of Montesa Motors arranged the use of the famed Ascot Park course for an afternoon. He brought along young John Hately’s own 250 for us to put through its paces. John had managed to clinch second in the Ascot Novice TT title chase, so this new five-speed was no stranger to the hard clay turns and heart swallowing jump.

It takes relatively little change to convert the 250 Cappra into suitable hard track trim—a different set of tires, 19-in. front wheel and handlebars that allow throttle control while steering in a slide. Any pattern that feels comfortable, and lets the rider slide back on the seat to give more traction to the rear tire, will do.

Tire selection is a little more complicated. Different types of surface demand different tread designs and rubber compounds. The Pirelli Universal, Dunlop K70, and the Goodyear All-Traction are the most widely used. A good rule of thumb to follow is to see what the winners at your favorite track are using and fit a similar pair to your machine. Mixing brands is sometimes quite successful. For instance a Pirelli in front and a K70 on the rear works well on dry, slippery daytime tracks. Cutting the tire to alter the existing tread design is another method of getting maximum traction on a loose or “cushion” type surface.

Hately’s machine has a 4.00-19 uncut Pirelli in front, and a 4.00-18 Dunlop K70 at the rear. This combination is just right for the hard slick Ascot course in the day time. The switch from 21-in. to 19-in. front wheel alters the steering geometry to give better front end loading, and allows the rider to push harder into the turns without the tire letting go.

The additions mentioned aren’t too expensive, and allow the purchaser to own a dual purpose machine. This is a welcome bonus to most riders, as they can afford only one motorcycle, and nearly every town in the country has a nearby flat-track styled playground.

Off Ascot’s starting line in the middle of the front straight, you accelerate deep into the half-mile turn. Two quick backshifts down into second sets you up for the off-camber left-hander leading into the infield. A quick left on the far side of the duck pond leads to a sharp horseshoe to the right just before the jump. Up the ramp you crest the top in third, and hang on until you come back to earth. As soon as the front wheel touches down, you backshift to second for a sharp right. Then sliding through a tight left, you taper onto the main straight. Shifting up at full throttle, you hold it on all the way into the sweeping half-mile turn for another lap.

The Cappra 250/5 is a good slider. The weight is down close to the ground, giving the rider control while crossed up. The machine goes where it’s aimed, and doesn’t give the feeling of wanting to highside. Getting in and out of tight corners is somewhat slow due to the long wheelbase, in fact, overall handling is slow, without any sudden pitching or surprise movements. This slowness can be somewhat beneficial, as it gives the rider time to think and act before he is in serious trouble.

The success of Ascot TT stars John Hately and Jimmy Raymond, Tim Hart, motocross ace, and other Montesa competitors across the country is proof that the 250 Cappra can perform. No doubt these riders’ outstanding ability and sheer determination were the contributing factors that put them in the winner’s circle. However, the fact remains that they did accomplish these victories aboard Montesas. Given the opportunity to perform where it is most suited, the new Montesa 250/5 will hold its own.

MONTESA

250/5 CAPPRA

$1040

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

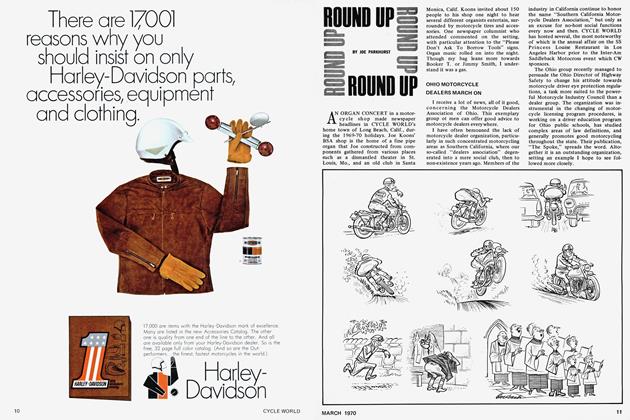

DepartmentsRound Up

March 1970 By Joe Parkhurst -

Departments

DepartmentsThe Scene

March 1970 By Ivan J. Wagar -

Letters

LettersLetters

March 1970 -

Features

FeaturesDoes Your Club Owe Income Tax?

March 1970 By Robert O. Fee -

Competition

CompetitionPolo Without A Feedbag

March 1970 By Heinz-J. Schneider -

Departments

DepartmentsThe Service Department

March 1970 By John Dunn