GREEVES 250 MOTO-CROSS

Cycle World Road Test

MOST OF THE THUNDER at the town of Thundersley, in England, comes from the small factory where the Greeves motorcycle is manufactured. For the most part, their output is devoted to outright competition machines, with very straight pipes and/or megaphones, and when the factory is doing development testing it must get very thunderous indeed.

There is, of course, a lot more at Thundersley than just noise, for Greeves motorcycles have absolutely decimated the 250cc displacement class for the past couple of years. Wins include such international prizes as the World’s Motor-Cross Championship in 1960 & 1961, and a gaggle of victories in lesser events. Here in America they did just about as well: picking up miscellaneous championships at every turn. In fact it appears as though they will not only utterly trounce everything in their own class, but will actually be a serious threat in the overall classifications as well.

Already, the 1962 race results have been showing the Greeves climbing right up there in the win-placeshow listings, and beating all of the “big-inch” machines while doing it. How do they do it? Their successes seems to be due to a combination of factors, and we’re not certain that any one of them can be said to be more important than any other. In any case, here is the Greeves; perhaps you can find its secret.

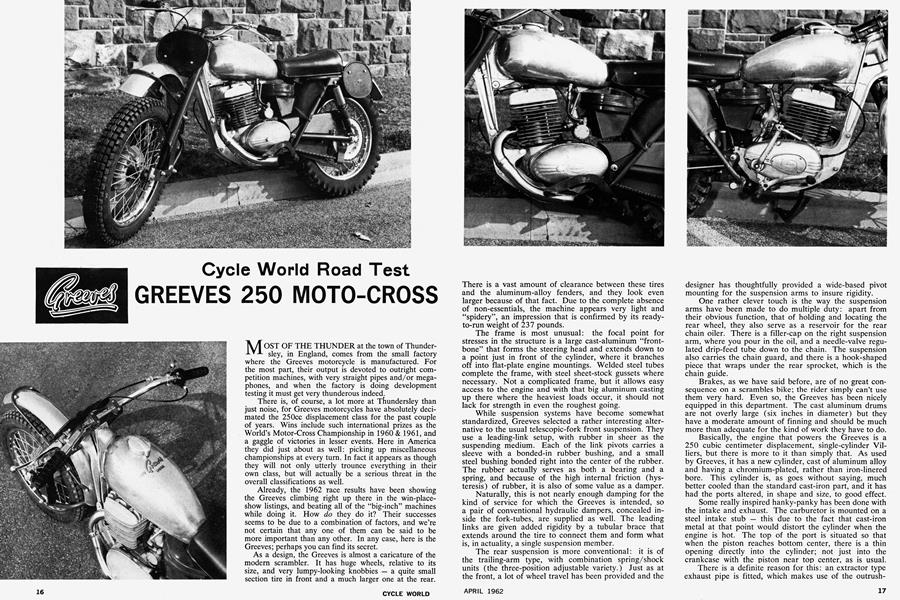

As a design, the Greeves is almost a caricature of the modem scrambler. It has huge wheels, relative to its size, and very lumpy-looking knobbies — a quite small section tire in front and a much larger one at the rear. There is a vast amount of clearance between these tires and the aluminum-alloy fenders, and they look even larger because of that fact. Due to the complete absence of non-essentials, the machine appears very light and “spidery”, an impression that is confirmed by its readyto-run weight of 237 pounds.

The frame is most unusual: the focal point for stresses in the structure is a large cast-aluminum “frontbone” that forms the steering head and extends down to a point just in front of the cylinder, where it branches off into flat-plate engine mountings. Welded steel tubes complete the frame, with steel sheet-stock gussets where necessary. Not a complicated frame, but it allows easy access to the engine and with that big aluminum casting up there where the heaviest loads occur, it should not lack for strength in even the roughest going.

While suspension systems have become somewhat standardized, Greeves selected a rather interesting alternative to the usual telescopic-fork front suspension. They use a leading-link setup, with rubber in sheer as the suspending medium. Each of the link pivots carries a sleeve with a bonded-in rubber bushing, and a small steel bushing bonded right into the center of the rubber. The rubber actually serves as both a bearing and a spring, and because of the high internal friction (hysteresis) of rubber, it is also of some value as a damper.

Naturally, this is not nearly enough damping for the kind of service for which the Greeves is intended, so a pair of conventional hydraulic dampers, concealed inside the fork-tubes, are supplied as well. The leading links are given added rigidity by a tubular brace that extends around the tire to connect them and form what is, in actuality, a single suspension member.

The rear suspension is more conventional: it is of the trailing-arm type, with combination spring/shock units (the three-position adjustable variety.) Just as at the front, a lot of wheel travel has been provided and the

designer has thoughtfully provided a wide-based pivot mounting for the suspension arms to insure rigidity.

One rather clever touch is the way the suspension arms have been made to do multiple duty: apart from their obvious function, that of holding and locating the rear wheel, they also serve as a reservoir for the rear chain oiler. There is a filler-cap on the right suspension arm, where you pour in the oil, and a needle-valve regulated drip-feed tube down to the chain. The suspension also carries the chain guard, and there is a hook-shaped piece that wraps under the rear sprocket, which is the chain guide.

Brakes, as we have said before, are of no great com sequence on a scrambles bike; the rider simply can’t use them very hard. Even so, the Greeves has been nicely equipped in this department. The cast aluminum drums are not overly large (six inches in diameter) but they have a moderate amount of finning and should be much more than adequate for the kind of work they have to do.

Basically, the engine that powers the Greeves is a 250 cubic centimeter displacement, single-cylinder Villiers, but there is more to it than simply that. As used by Greeves, it has a new cylinder, cast of aluminum alloy and having a chromium-plated, rather than iron-linered bore. This cylinder is, as goes without saying, much better cooled than the standard cast-iron part, and it has had the ports altered, in shape and size, to good effect.

Some really inspired hanky-panky has been done with the intake and exhaust. The carburetor is mounted on a steel intake stub — this due to the fact that cast-iron metal at that point would distort the cylinder when the engine is hot. The top of the port is situated so that when the piston reaches bottom center, there is a thin opening directly into the cylinder; not just into the crankcase with the piston near top center, as is usual.

There is a definite reason for this: an extractor type exhaust pipe is fitted, which makes use of the outrushing slug of high velocity exhaust gases to create a partial vacuum in the cylinder and pull a final puff of fresh mixture right across the top of the piston. Although this sounds a trifle peculiar, tests have shown that the pressure inside the cylinder falls to as much as 10 p.s.i. below atmospheric after the exhaust charge leaves the cylinder. The test bike we were given had 21 bhp and-a-fraction, but we just received word that detail improvements have boosted this to 23 bhp — and have added another 1000 usable rpm right onto the top.

Test riding the Greeves was, of course, of necessity, confined to off-the-road expeditions. Not only that, but we had to take it out well beyond civilization, because it has a short, flat megaphone exhaust system that will break windows for about a mile. Ear-plugs or one of McHal’s “Akusta-Bloc” helmets is almost a must for Greeves riders. The exhaust system is efficient, there is no denying that, but it has about the same tone and amplitude as a rapid-fire 40mm cannon and it does create a fearful din.

From the scrambles rider’s viewpoint, the Greeves is as perfect a bit of machinery as is likely to be built by mortal man. The seat is rounded at the edges and is soft enough, and the foot-pegs stand up out of the way and, incidentally, look as though they couldn’t be knocked off with a hammer. The fuel tank is narrow, made of rolled aluminum, is beautifully polished and, as a piece de resistance, has an aluminum snap-release racingtype filler cap. The handlebars are wide and rather straight, with just enough rise to be comfortable and give good control whether the rider is sitting or standing on the pegs. The whole businesslike ensemble is given the final touch by the three oval number plates, which are finished in a flat black.

One’s first ride on the Greeves is likely to be somewhat exciting, as it has a great deal more sheer power than the average rider is expecting from a 250. Our initial run was made up a favorite, steep incline, which had, unfortunately, been rutted by a recent rain and then baked hard by the sun. CW’s intrepid test rider was away with a rush, and got up much more speed than was prudent for a first-acquaintance trial — with the inevitable result that the ride ended in a series of really phenomenal, bounding leaps that nearly dropped our hero on his helmet-clad noggin. Later, more restrained tries at the same slope gave more satisfactory, if less exciting, results and we all acquired great respect for the good manners of the Greeves when it is given just halfa-chance.

Before our trials were over, we became very aware of two of the Greeves’ outstanding characteristics: First its light weight and long-travel suspension make it relatively easy for the rider to maintain control of any situation; and second, that it has power to burn. It may simply be due to the gearing and light weight, but for whatever reason, the Greeves has about as much punch as most of the good 500cc bikes. The power is there all the way, too. Almost from idle, you can roll the 174turn throttle open and expect things to happen, and to stay happening until the power begins to fade at approximately 7000 rpm. With such a broad power spread, you don’t have to do much shifting; you merely keep cranking it on and gaining speed.

If we sound like big boosters for the Greeves, it is because we are. Indeed, we liked it so well that one of our staffers promptly bought one — and when you put up money to back your opinions, there isn’t really any higher praise you can offer. •

GREEVES

250 MCS

SPECI FICATIONS

$795.00

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

The Service Department

April 1962 By Gordon H. Jennings -

Cycle Round Up

April 1962 By Joe Parkhurst -

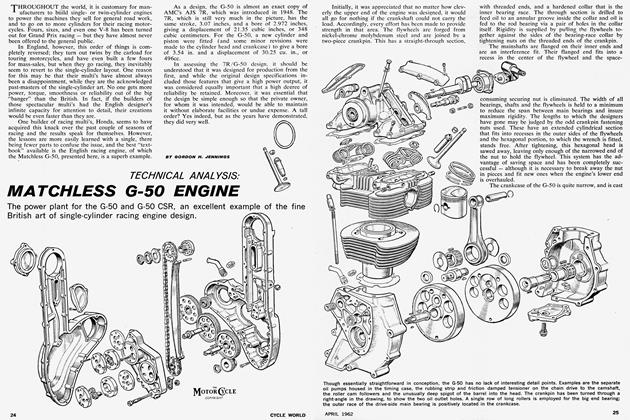

Technical Analysis: Matchless G-50 Engine

April 1962 By Gordon H. Jennings -

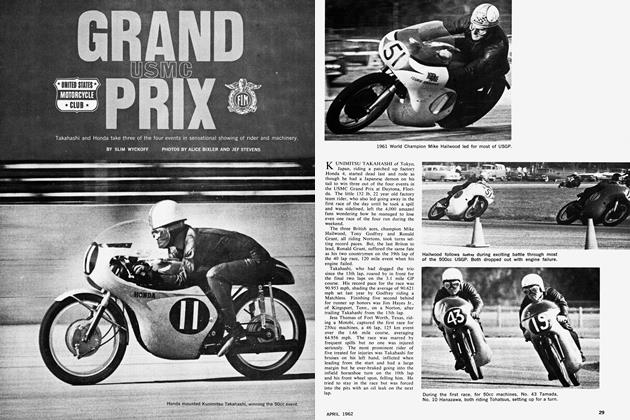

Grand Usmc Prix

April 1962 By Slim Wyckoff -

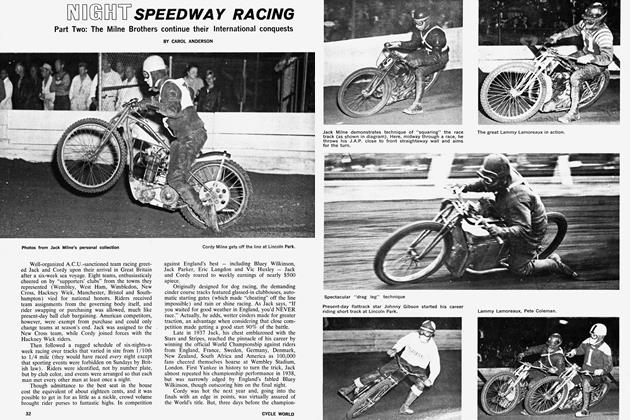

Night Speedway Racing

April 1962 By Carol Anderson -

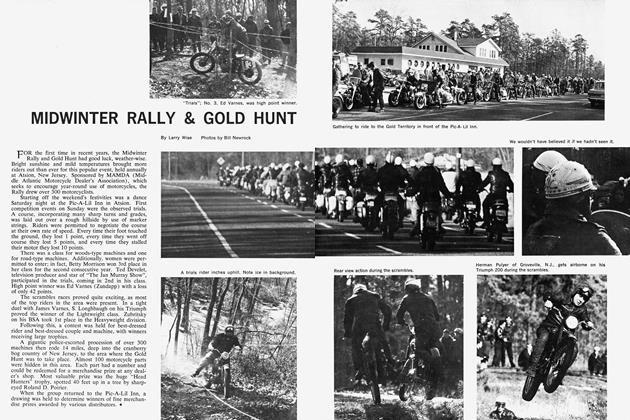

Midwinter Rally & Gold Hunt

April 1962 By Larry Wise