I'M SO GLAD

Into Every Turn Of The Throttle, Into Every Degree Of Lean Is Woven The Texture Of A Man's Life.

MARK LUNDE

WHEN I WAS SMALL and my eyes burned red and golden, alive, like the sunset, I'd stand on the porch

feeling silver in my pocket, overlooking the river, and across the river at the carnival with its violent lights turning softly in my brain, laughing. When I was young, my veins ran full and warm.

I loved cotton candy and the tilt-awhirl and I really loved the freaks. I really did.

But 1 loved the motordrome more. Around and around, flashing, lips ripped back over his teeth, rising black and hot and dirty. Around and around. Noise and stinking smoke. So close you can reach out and smash your forearm against his speeding throat. Send him crashing and pounding along the boards, spiraling and cracked and exploded over the edge and suddenly, everyone in the tent feels the urge. It’s so easy, so very easy.

When it was over, 1 followed him out of the tent and, like an animal shadow, to his trailer. It was long, wooden and painted white. There was a huge, grinning skull on the side wearing goggles and a leather flying helmet and underneath the skull were two words, three feet high, fashioned in red with black trim.

And the words said: DEATH RACER. He left his door part open and a thin slice of yellow light filtered sickly, into my eyes. / took a look.

He was retching, with his back towards me, onto the kitchen floor and, y’know, when 1 come to think of it, he must have realized that somewhere, there's a sharp, blood-crusted edge. It's the edge between sanity and insanity. We all walk that edge, like a tight-rope walker, cutting up our feet.

Once in a while, somebody slips.

“Eighty,” said sly Peter with a smile. He looked at me, then clasped his hands behind his head and leaned back in his chair.

“Mind you,” he continued,” I was drunk and them tires was a’screeaming, but I made it, by God. Yes siree!”

He threw me a glare and I knew he had me.

“And that lake. Wow! I figgered I was going to get sucked in for sure. I’m telling you, it was just a reaching right out for me and the old panel.” He paused. “But I made it.”

Jim sat, half bored, waiting for Peter to unload the big one. Suzy looked at me, knowing that Peter was lying through his teeth. She knew about me, too.

“Well”, said Peter, “how fast have you made it?”

“About sixty,” I said. I had told the truth and had immediately regretted it.

“'Eighty,’ said Sly Peter With A Smile.”

“Not bad,” said Peter, “for a bike. Now if you had yourself a Harley, something with a little weight, you could probably make 75 around Yellow Lake. Of course,” he admitted, “that would be pushing it.”

“You’re really good, Peter,” said Suzy. But it didn’t do any good, because Peter thought she meant it and his nose took on the purple hue of satisfaction. It ruined my whole evening. The rest of the night I spent looking for something in Suzy’s face and found nothing but a whole lot of irony. She knows, you see, only she doesn’t care. Well, anyway, Jim argued with Peter for a couple of hours and at about 1 a.m. Suzy’s old man awoke to announce that he was kicking the three of us out. He also said that although he had nothing against us all personal, we was all a bunch of crazy buggers. That was all right since we thought he was a crazy bugger, too.

When we left, Suzy stayed at the window to watch me start playing with my reliable Ducati. Jim’s Super Hawk started after two kicks, Peter’s panel had no trouble at all throwing a little gravel at us, and I tickled the carb, gave her two compression strokes and after nine colorful and romantic prods, gave up and started running her. This is all par for the course. My Duck started to rumble and jump up and down, sort of, because it’s a Single. I circled back down the street and rejoined Jim back under Suzy’s window.

I looked at her and she was laughing. I didn’t mind. I never do. When she laughs, it’s a good laugh. It’s honest and clean. I gave her a half-hearted gesture with my thumb and a grostesque Frank Zappa grin. Then Jim and I rode into town, looking for something to eat.

Penticton’s got a long main street that stretches from one soupy lake to another. The idea of the long main street is to give an illusion of bigness; small majesty and cheap splendor. On either side of the street are houses, not many businesses, just houses. Folks live in these houses, wake up and rise, cursing, and all through the day they sweat and hate. Some grovel, a whole lot grovel, and they all hate, at least most do, and they go to bed cursing, cold, and they all hate and they have rotten dreams. At least most do.

It’s a strange town. It can kill you. People like Suzy survive, only because they are pure, or something.

“My Duck Started To Rumble And Jump Up And Down, Sort Of, Because It’s A Single.”

Penticton’s a tourist town and in the summer it really comes to life. There are about 50 motels, varying in relative degrees of shoddiness, all strewn along the main drag. In July and August the place bloats with Americans. It attains the quality of a clogged sewage pipe. They come from Washington, Idaho, Oregon, California, even Kentucky and New York. They come with water bags strapped to their cars. They come to rough it, up country. And they spend a lot of money. That’s how Penticton makes it.

It’s a leech town and it’s pretty, like a painted corpse. And it’s mean.

We were heading for the A&W, nipping casually in and out of cars, when we met up, right flush, with a stop light. A pink and black ’54 Plymouth pulled up beside us. “331 Hemi” was crudely printed above the front fender in black felt pen. There were six guys in the car with two chicks. One girl was vomiting wine out of the back window, very close to Jim’s bike. That sort of thing gets him very uptight. He takes it as a personal insult. With the palm of his hand he reached over and pushed her head into the car. She hammered her head against the door and swore with a vileness that I couldn’t believe. Then she vomited in her boy friend’s lap.

(Continued on page 75)

Continued from page 55

I was all set to start laughing when the driver stepped out of the car. He certainly was ugly. He was big, too. The light was still red but there was a lull in traffic. Jim gunned it and the front wheel started bouncing like a basketball. He was standing on the pegs, laughing, and screaming obscenities all across the intersection. I began fishing for first, found it and began slipping the clutch. A fast boot snapped off the top of my helmet but I got off okay and we left the Plymouth wallowing, stupidly, at the light.

“Whayawat?” said the girl.

“Papa Burger,” I said. I was ready to make a smart answer but thought the better of it what with all the parked customers and the fact that she might try to hit me. She looked at me, crinkled her nose and walked off with our order.

“Nice girl,” said Jim crinkling his nose.

“Yeah,” I said, “too bad.”

When our food came I was too engrossed in cold onions to notice what had pulled into the lot.

I caught Jim’s eye. He was sitting sidesaddle on the Super Hawk, grinning, and pointing his finger behind us.

“Greeaasse,” he hissed.

I turned my head and nearly choked on my hamburger. Our friends in the Plymouth had found us. Jim got off the bike and walked over to the car. I had a horrible, cold feeling like my bike didn’t want to start. Jim leaned against the door like a speed cop and smiled.

“Hi,” he said loudly. “How are ya?”

Not that I haven’t seen it all, or nothing, but the thing is, it always get me. How Jim can take people in. I remember once, at a dance in Oliver, how Jim had convinced a punk that the punk didn’t really want to beat him up, he wanted to beat up his girl friend instead. Predictably, the girl had nothing to do with the argument. The guy started pushing his way through dancing couples, in a rage, looking for his woman. He got about halfway across the floor when Jim snuck up behind him and smashed his helmet against the back of his head. The dope sprawled, spread eagled, into the refreshment table. Jim ran for the exit and made it.

So, for about five minutes, I had the pleasure of watching Jim do his stuff.

I saw the driver’s face turn from pale, controlled anger to vague distrust to dreadful remorse, and finally, to absolute, childlike faith, realization of an old truth, long since forgotten. He stepped out of the car and shook Jim’s hand, solemnly. Then he stepped back into the car and motored quietly out of the lot.

When the waitress returned to take our tray, Jim bluntly propositioned her. She refused, equally bluntly, and Jim thought this was very funny. And so did I.

Keremeos, where we live, is about 30 miles south of Penticton. It’s a long ride, especially during July and especially at night.

A warm wind was hustling down the mountain slopes, nudging us along in dark gentle waves. h The moon was out, full, its fallen, murky reflection touching softly, upon tall pines that rested above and looked down upon the twisting highway, casting long, rolling shadows.

The Mark I was chugging under me, her sleepy thunder floating in my helmet. Jim’s Honda moved on ahead of me, dipping in and out of easy turns, puttering along.

It’s on nights such as these that I remember all my dreams and wonder why they never turned out. I remembered my first bike and I remembered my first love. The bike was great, a 180 Yamaha, and it wanted to last forever. It burned down the hot pavement and it burned, hot in the wind.

But I botched it with the girl, read bad. I thought of Suzy and began dreaming again, feeling funny. She was different, so much better, and I’m dreaming. I’d dream my life away.

It’s so much better than reality.

Now the wind changed and it ran cold in my face. We were nearing Yellow Lake. The wind always changes there. It becomes harsh and brittle and I don’t know why. It’s a callous slap across the face and it wakes you up.

“I don’t like this lake,” said Jim. “It scares me.”

Nobody likes Yellow Lake. You slow down before you reach it and you speed up after you pass it. You get the feeling it wants you. It's a dead lake, no fish can live in it and it’s supposed to be bottomless. It’s buried in a grey, deep bowl of mountains and the wind is always whipping fast and sullen over its surface.

Last January, they found another body. Somebody noticed something blue sticking out of the ice. It was a knee. And it belonged to a girl who had plunged her MG Midget into the lake. They had found the car; they hadn’t found her. When they found her, Constable Larch, who is an old man and very kind, said that she must have been very pretty, but part of her face had decomposed. She had crashed through the guard rail around the corner. The corner introduces you to the lake, smiling.

Come, meet the corner.

A massive chunk of rock knifes into the lake and the road skirts the rock in a half circle. Below and beyond the corner there’s the lake, sitting toad-like and patient. A sign reads: Slow To 25.

It means it. The rock is composed of chert. It’s almost as hard as diamond and it’s sharp as glass. A stray piece can rip up your tires plenty good. On a bike, that’s killing. There’s a long straight leading up. You can get a good run at it.

Wanna try?

We perched now, Jim and I, like ravens upon the guard rail. We looked down on the sloping, jagged plane of rock and wooden debris that had sunk into the lake. I bit my front teeth into the filter of my smoke and took a deep puff. I considered, briefly, how bad I’d be coughing in the morning. I could see myself, wheezing and hacking, spitting slime into the sink. One more gulp settled, fitfully, into my lungs. I flicked the butt into the water and it died with a small, hideous whistle. Behind me, the Super Hawk rested silently on its side stand. My Ducati was idling, erratically. Then it quit. I got up and, muttering weakly, turned off the key and the gas. “There’s no way,’ said Jim quietly.

“Nobody Likes Yellow Lake ... You Get The Feeling It Wants You.”

“No way what?”

“No way,” he replied,” that Peter could take it at 80. None.”

None at all. But that don’t matter to Peter. He is now convinced that his Thames panel will out handle my Ducati and anything else on the road. Whether it will or or not is of no concern. Peter believes that it will.

Peter is somebody that nobody thinks about, except me and Jim, and somebody that nobody forgets. He’s about five feet four with a brilliant splurge of red hair that’s shaved almost bald at the sides and back, but it really comes into its own at the top of his head. His eyes are small, clever slits with pink, puffed lids. His nose is long, pliable, and drooping, extending down to one quarter of an inch from his lips which are, perpetually, up turned and convey, to me, a horrid sensation. Peter is satisfied. Very much so.

He sets small goals and he overreaches all of them.

One of his aims in life is to upset me. He performs this feat admirably.

“But the top of third,” I said, “must be a good 90!”

Jim kicked the side stand up under the muffler.

“I know,” he said.

He clunked it into first and started edging around the corner at about five miles per hour. He was looking it over. Three times he dismounted and threw a piece of chert into the lake. Once he stopped and, with his foot, swept some gravel onto the shoulder. He went over his line again, turned around and went over it once more. Seven times. Then he rode over to where I was sitting on the guard rail.

Continued from page 75

“I can do it,” he said, hoarsely.

He gave it a healthy, serious zap in first, eased off, placed it in third and rolled down the straight. I watched his headlight disappear as he turned into a slow curve and dropped behind a thick springing of pines.

Somewhere, a starling sang an ugly song. I looked up. There was a tree on the mountain, on the rock, just above the lake, just above me, looking down. And the tree was dead and it cupped a starling in its web of branches. It spoke to the starling, it whispered. It whispered: I love you. And the moon burned, cold, like fingers through the branches and the starling, its eyes icing over, fell silent. The starling, its small wings forever stilled, had nothing to say.

Suddenly, in the distance, there was this great, long shotgun blast, great and long, reverberating, and it roared. I could see it; the front wheel of the Super Hawk lanced, proud and erect, in the air, bounding up, poised, dropping. It came heaving and screaming down the straight, a red rocket, dancing, a red rocket burning with flame, fast and loud.

Jim went into it as best he could.

He didn’t come out.

His teeth were bared and I couldn’t hear it, but I think he was shrieking. His eyes were straining to get out of his head. He was halfway around the corner and he was starting to slide. His right leg was out, spider-like, trying to hold it up, he was sliding at an insane, pitiful angle, sliding.

He was sliding towards the lake. That’s why he was shrieking. The lake was going to take him into her. She reached out her cold arms. Jim dropped the bike. Its headlight smashed out on the pavement and, in darkness, it released a hot flurry of sparks, its skin shredding in blue, red and gold. Then it lodged under the guard rail, ten feet to my left. The back wheel whirred, spinning out tiny grains of dirt. The chain clicked like a metronome.

But Jim had no rhythm to his movements. He was rolling and tumbling on the road. Jerking and flailing. It was as if the earth-mother had started playing with her child, tossing him up and down in the air. Only she played too rough.

Jim lay on the road, quiet, and there was blood running out of his mouth.

Jim waited all through August. He waited a long time and there was a plastic tube pinned into his left nostril and there was another tube flowing out of his right arm. Suzy and I knew what they were there for but we didn’t talk about it. Sometimes his mouth would fall open and you could hear him breathing. It always sounded as if his lungs were filling with mucous. It was a sort of rasping gurgle, barely audible. He wasn’t well, you see, apd his skin had turned yellow and his eyes, when they opened, were pink and they ran a lot. Suzy and I used to think he was crying. He wasn’t.

He was fighting and it hurt.

That summer, I lived a dream and, for a while, it worked. I almost made it with Suzy but I never followed it through. I used to dream about making it with her but I never imagined the real thing would be tinged with doubt and suspicion. It was. Slick Peter saw to that.

Still, we had a lot of fun. She was a natural passenger and we used to like to ride south into the strange American wonderland. We’d leave in early morning and return in the late evening. Between morning and evening, it was all ours.

The sun would meander through the sky; it would reach across the land and release its mellow radiance. It would rest upon us. It would rest upon friendly lakes, too, upon gentle roads and deep tanned faces, upon red and white homes and through windows and into rooms; into rooms upon whose walls still hung the heavy, giddy fragrance of 5 a.m. coffee.

It was so good. The hot, furnace-like air split in our faces and we smiled, and sometimes, when it was really warm, the sweat ran free under my helmet. The long highway rumbled under us like a kindly strip of brooding, earthy sea. We sailed this narrow sea and we crossed vast, dry plains marred only by the occasional series of faded Burma Shave ads. We laced through long, tall bridges and hummed along green rivers and under trees. We rode, two maybe three hundred miles a day, through small towns and small adventures. Each town was an adventure, each street and face. Every steaming inch of road, every gear change, every breath of wind, an experience. It was all so good and, one day, the last day of August, I glanced down at the Ducati’s tach and listened to her strong heart, and I felt Suzy, snug behind me, very near and close, and all of a sudden, it came to me like a lightning bolt coursing through my brain. I was living my dream.

All towns were wonderful that summer, but Nighthawk, sleepy under the sunset, was the most wonderful of all. It was huddled around the Okanagan river, which was clear and fresh, and the whole town was cooled by its caresses which rose and enveloped it in soft, flowing drafts. The river banks were covered generously, with old cottonwoods and cedars, a cluster of them, tall and straight, swaying in the breeze. And somewhere beneath all these trees, and between them, Nighthawk lay — hidden and buried.

So, it was during that last day in August that Suzy and I pulled into Nighthawk. It was the first time I’d ever seen or heard of the place. The Ducati had a near empty gas tank, so we rattled over a bridge and coasted into a filling station. Suzy got off and I pulled the bike up on to the center stand where it wobbled for a second and then remained steady. The attendant, a wrinkled old sparrow, exploded out of the screen door with a grin.

“Nice dây, ain’t,it,” he said.

We replied that it was and I asked him to fill it up.

The filling station doubled as a general store with two yellow and blue, circa 1930 gas pumps propped outside. A bright American flag cracked and blazed its colors on the roof. A dusty street with wooden sidewalks ran alongside the place with about ten old houses with picket fences and well kept lawns strewn on either side. The main highway continued on its own. Only a dirt road dropped off the bridge and led into town.

“Somewhere There’s A Place Where You Don’t Have To Be Concerned Or Involved Or Unhappy ... It’s Very Near, Only It’s Very Hard To Find.”

“This is it,” said Suzy.

I didn’t catch on right away, so I looked around. A balding man was waxing a ’49 Ford with slow, hard strokes, down the street. A little kid was sitting on the ground, polishing a hubcap. The man was singing with a piano. The piano was rippling out of a window somewhere near. He wiped a film of sweat from his brow then looked up at us and waved. Then he sang with his heart hung on every note.

“One of these days, you’re gonna rise up singin’,

You’re gonna spread your wings and

fly”

A massive colored woman trundled in a garden. She was working, her hoe chunking into thick, moist clumps of soil. An elderly couple, in pink and gold, sat on a porch a few houses down the street. A jug of frosted lemonade was placed on a marble topped table in front of them. They sat on a long chair suspended from the ceiling by chains and they swung, like a pendulum, back and forth.

“This is it,” said Suzy, “the place we’ve all been looking for.”

Where the world is filled with wonder. Where times don’t change, yet are not stagnant, where the days are filled with wonder, forever. A place where you don’t have to be concerned or involved or unhappy. A place where you can be left alone. Somewhere in the back of your head, sleeping, a place and a time, come true. It’s not far away, it’s very near, only it’s very hard to find.

I found it, just once.

It was a long ride that night, about 70 miles, from Nighthawk to Suzy’s place.

I felt so weird, when we got there. I mean it was weird and fantastic and I couldn’t say anything. I just couldn’t. So I just looked at her. Then I rode away.

And, feeling weird and fantastic, I took Yellow Lake corner at 75.

Suddenly, on the first of September, it was gone; it just went away. It died, it sunk into the earth and it was gone.

„ ‘Hell,” said Jim, his face all puckered sour. “I’ve missed all the lousy summer.”

He had, too, because it was gone.

“Plunk,” said the striped three.

“Plunk,” said Jim, limping around to the other side of the table.

We were playing pool in Keremeos and it was a Friday night in the middle of a cold October. Outside, the north wind was running quick in the streets. It was slamming around buildings like a sudden flood of hellish ice water, spewing like blood from a hole in the earth, slithering and freezing under doors and rifling through spider webs of cracked glass. Glass and doors and shudderings and sudden blasts of gritty dust with careless newspaper pages caught in the wind like kites and confused clatterings and quiet unlatchings and a brisk step inside with small curses and there in the pool hall stood Peter, his thin red lips stretched over his teeth like a ghoul, grinning.

“At The Top Of Third, I Started To Have My Doubts.”

Tip, the proprietor, sat in his dark corner, behind the counter, the' ancient 16-inch television casting an eerie, faded blue glow on his face. He sat, absorbed, the door crashing to and fro in the wind. Peter stood in the door way, his feet braced apart, the overhead lamps glinted, catlike, pale and sharp, in his eyes.

He threw me a glare and I knew he had me.

Only I didn’t know what he had me on.

Then, there was a small gypsy-monster creating fire from his fingers. He made it and he left it behind him. There was a sudden quilt patch of flame in the night, then nothing, and, somehow, the gypsy-monster had acquired two others. And they walked an alley with a rustle of satin and a soft cracking of knuckles. They sniffed the air and, like the flutter of a bat wing, whisked under a street lamp. They appeared, briefly, like black horses, flying and silhouetted, against an Autumn moon.

I haven’t been in one for a while but I’d say that it was a pretty fair night for a thirty-first of October.

It was the night I got my big surprise.

I rode down the Penticton streets and on each side there were small 'gatherings of little kids all done up in white sheets and plastic vampire teeth, sticky, rubber masks and purple wigs. There were long, staggered caterpillar strings of them, sometimes, lined up behind an open door. In the doorway there’d be a mother, all smiling and bending down at the knees, and behind her there’d be a round two-footer, gazing out on the fantastic menagerie of children a few years beyond her; she’d gaze in awe and savour the gentle tartness of her first chunk of candy apple.

When I arrived at Suzy’s place I rang the buzzer and was greeted by her father. He wore a suit with a loosened pink tie. Down the hallway a surge of fake jazz trumpets came rolling out at me accompanied by a rattling of loud voices and, behind all this, there were many electric smiles. They burst on like flash bulbs and they faded quickly. It was a party and it came complete with cheap flirtations, black lies and little games, instant headaches, liquor and a dash of ugliness.

Well, I figured I had it all over them but when I was told that Suzy was out with Peter it drove through my brain like a hot bullet.

“Welcome back,” said the corner, smiling.

And I rode around the corner very slowly at about five miles per hour and when I reached the end of it I turned around, stopped and dismounted, and threw a piece of chert onto the roadside. I did this several times. Then I got back on and went a ways down the road. I wanted to get up a good head of steam.

The moon had sliced behind a black mountain side and it rested there, half hidden, and stared; its thin vision hung in the night, clear as ice. My Ducati was an animal and she waited, her golden eye reaching blindly up the road. With a crack of exhaust, the golden eye jerked up into the air and was moving down the line ...

At the top of third, I started to have doubts.

My Ducati isn’t much of a singer but she keeps good time and as soon as we passed Yellow Lake she kept time to a song first done in 1923 by Skip James and more recently by the now defunct Cream.

I can still remember Jack Bruce’s voice barreling out:

You’re leavin’, you’re goin’,

And I don’t know what to do, yeah,

But, I’m so glad, I’m so glad,

I’m glad, I’m glad, I’m glad ...

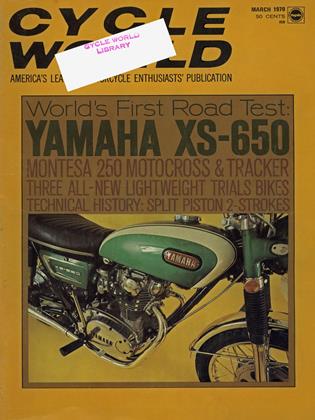

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsRound Up

March 1970 By Joe Parkhurst -

Departments

DepartmentsThe Scene

March 1970 By Ivan J. Wagar -

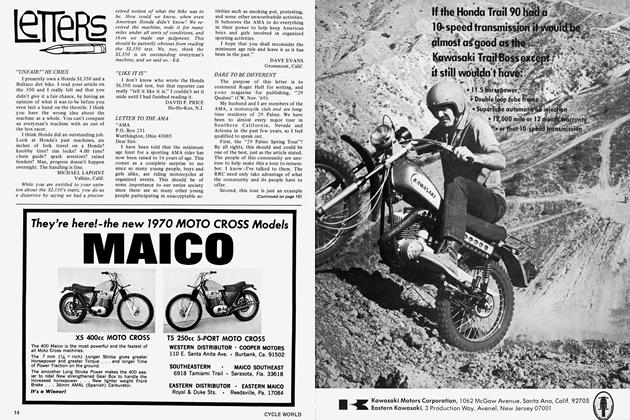

Letters

LettersLetters

March 1970 -

Features

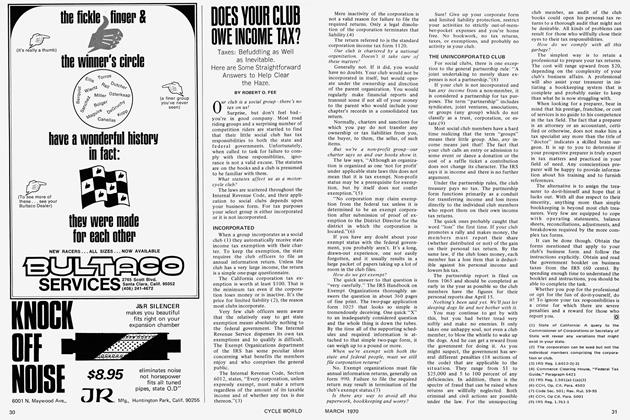

FeaturesDoes Your Club Owe Income Tax?

March 1970 By Robert O. Fee -

Competition

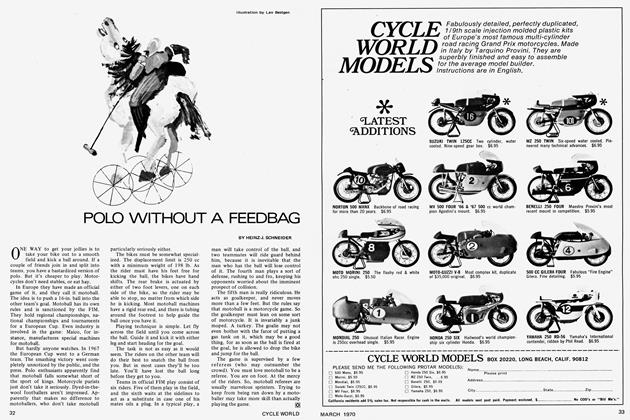

CompetitionPolo Without A Feedbag

March 1970 By Heinz-J. Schneider -

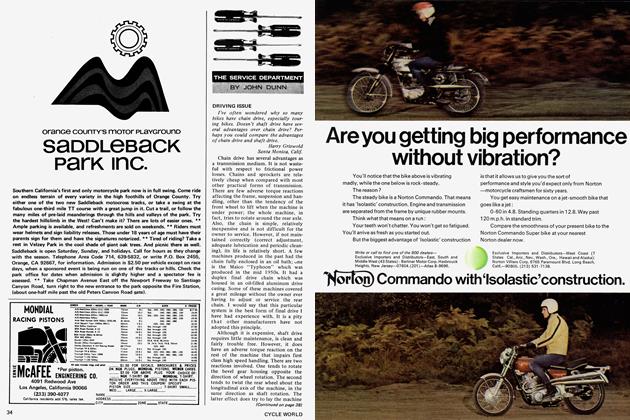

Departments

DepartmentsThe Service Department

March 1970 By John Dunn