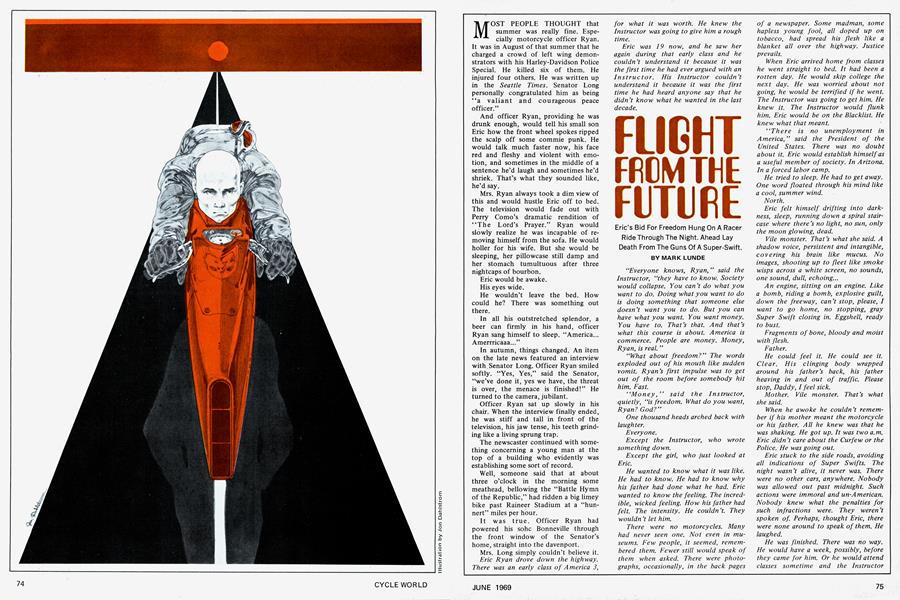

FLIGHT FROM THE FUTURE

Eric's Bid For Freedom Hung On A Racer Ride Through The Night. Ahead Lay Death From The Guns Of A Super-Swift.

MARK LUNDE

MOST PEOPLE THOUGHT that summer was really fine. Especially motorcycle officer Ryan. It was in August of that summer that he charged a crowd of left wing demonstrators with his Harley-Davidson Police Special. He killed six of them. He injured four others. He was written up in the Seattle Times. Senator Long personally congratulated him as being “a valiant and courageous peace officer.”

And officer Ryan, providing he was drunk enough, would tell his small son Eric how the front wheel spokes ripped the scalp off some commie punk. He would talk much faster now, his face red and fleshy and violent with emotion, and sometimes in the middle of a sentence he’d laugh and sometimes he’d shriek. That’s what they sounded like, he’d say.

Mrs. Ryan always took a dim view of this and would hustle Eric off to bed. The television would fade out with Perry Como’s dramatic rendition of “The Lord’s Prayer.” Ryan would slowly realize he was incapable of removing himself from the sofa. He would holler for his wife. But she would be sleeping, her pillowcase still damp and her stomach tumultuous after three nightcaps of bourbon.

Eric would be awake.

His eyes wide.

He wouldn’t leave the bed. How could he? There was something out there.

In all his outstretched splendor, a beer can firmly in his hand, officer Ryan sang himself to sleep. “America... Amerrricaaa...”

In autumn, things changed. An item on the late news featured an interview with Senator Long. Officer Ryan smiled softly. “Yes, Yes,” said the Senator, “we’ve done it, yes we have, the threat is over, the menace is finished!” He turned to the camera, jubilant.

Officer Ryan sat up slowly in his chair. When the interview finally ended, he was stiff and tall in front of the television, his jaw tense, his teeth grinding like a living sprung trap.

The newscaster continued with something concerning a young man at the top of a building who evidently was establishing some sort of record.

Well, someone said that at about three o’clock in the morning some meathead, bellowing the “Battle Hymn of the Republic,” had ridden a big limey bike past Raineer Stadium at a “hunnert” miles per hour.

It was true. Officer Ryan had powered his sohc Bonneville through the front window of the Senator’s home, straight into the davenport.

Mrs. Long simply couldn’t believe it. Eric Ryan drove down the highway. There was an early class of America 3, for what it was worth. He knew the Instructor was going to give him a rough time.

Eric was 19 now, and he saw her again during that early class and he couldn’t understand it because it was the first time he had ever argued with an Instructor. His Instructor couldn’t understand it because it was the first time he had heard anyone say that he didn’t know what he wanted in the last decade.

“Everyone knows, Ryan, ” said the Instructor, “they have to know. Society would collapse. You can’t do what you want to do. Doing what you want to do is doing something that someone else doesn’t want you to do. But you can have what you want. You want money. You have to. That’s that. And that’s what this course is about. America is commerce. People are money. Money, Ryan, is real. ”

“What about freedom?” The words exploded out of his mouth like sudden vomit. Ryan’s first impulse was to get out of the room before somebody hit him. Fast.

“Money,’’ said the Instructor, quietly, “is freedom. What do you want, Ryan? God?”

One thousand heads arched back with laugh ter.

Everyone.

Except the Instructor, who wrote something down.

Except the girl, who just looked at Eric.

He wanted to know what it was like. He had to know. He had to know why his father had done what he had. Eric wanted to know the feeling. The incredible, wicked feeling. How his father had felt. The intensity. He couldn’t. They wouldn’t let him.

There were no motorcycles. Many had never seen one. Not even in museums. Few people, it seemed, remembered them. Fewer still would speak of them when asked. There were photographs, occasionally, in the back pages of a newspaper. Some madman, some hapless young fool, all doped up on tobacco, had spread his flesh like a blanket all over the highway. Justice prevails.

When Eric arrived home from classes he went straight to bed. It had been a rotten day. He would skip college the next day. He was worried about not going, he would be terrified if he went.. The Instructor was going to get him. He knew it. The Instructor would flunk him. Eric would be on the Blacklist. He knew what that meant.

“There is no unemployment in America,” said the President of the United States. There was no doubt about it. Eric would establish himself as a useful member of society. In Arizona. In a forced labor camp.

He tried to sleep. He had to get away. One word floated through his mind like a cool, summer wind.

North.

Eric felt himself drifting into darkness, sleep, running down a spiral staircase where there’s no light, no sun, only the moon glowing, dead.

Vile monster. That’s what she said. A shadow voice, persistent and intangible, covering his brain like mucus. No images, shooting up to fleet like smoke wisps across a white screen, no sounds, one sound, dull, echoing...

An engine, sitting on an engine. Like a bomb, riding a bomb, explosive guilt, down the freeway, can’t stop, please, I want to go home, no stopping, gray Super Swift closing in. Eggshell, ready to bust.

Fragments of bone, bloody and moist with flesh.

Father.

He could feel it. He could see it. Clear. His clinging body wrapped around his father’s back, his father heaving in and out of traffic. Please stop, Daddy, I feel sick.

Mother. Vile monster. That’s what she said.

When he awoke he couldn’t remember if his mother meant the motorcycle or his father. All he knew was that he was shaking. He got up. It was two a.m. Eric didn’t care about the Curfew or the Police. He was going out.

Eric stuck to the side roads, avoiding all indications of Super Swifts. The night wasn’t alive, it never was. There were no other cars, anywhere. Nobody was allowed out past midnight. Such actions were immoral and un-American. Nobody knew what the penalties for such infractions were. They weren’t spoken of. Perhaps, thought Eric, there were none around to speak of them. He laughed.

He was finished. There was no way. He would have a week, possibly, before they came for him. Or he would attend classes sometime and the Instructor would publicly blacklist him before the session started. Eric remembered once he had witnessed a Blacklisting. A gangly kid with thick glasses. He never got out the door. A few AYPs (American Youth Party) started pushing him around. Somebody hit him. Again. He went down. He looked as if he had fallen out of his clothes. Somebody stepped on his face.

Eric laughed again. It was better to be picked up by the Police. This was as good a time as any.

Twenty miles south of Seattle, on an old country road, he suddenly wished he hadn’t been so stupid in America 3. He could have got to know the girl.

Off the road and to the left, there was a light. It was moving through the dark forest. Eric turned off the car, doused the lights and listened. He thought he heard a chain saw, only softer.

His hands were moist and when the light burst onto the road, he was ready. Eric knew what it was. He knew who it was. It dropped onto the road, its rear wheel hitting first, the front wheel easing down. It stopped. Eric switched on the lights and they burned into her like an accusation. Like a threat.

A thought erupted in Eric’s brain. He could see himself exposing her in America 3. He could see himself redeemed, written up in the Times. He could see an A YP pushing his shaved head between her breasts, snarling.

Eric jammed the car into first, but the girl already was moving down the road, the front wheel heaved up into the air, her hair unfurled in the wind like a flag. She was about a hundred feet ahead of him, flat against the gas tank, her feet tucked up onto the back of the seat. Eric felt that she would fall off. The angle at which she negotiated turns was incredible. The bike would slide from under her. He wanted to stop. She’d get killed.

As the needle touched the 80 mark, Eric realized that he was gaining on her, and at 83, as he was within 50 feet of her, he realized he was going off the road.

Mr. Hendricks looked down at Eric, whose head rested on a pillow stuffed with feathers rather than foam rubber.

“So that’s the Ryan kid, eh?” he said.

“He’s the one I was telling you about, Dad,” said Miranda.

“Christ, why didn’t he die?”

Mr. Hendricks turned away and walked into the kitchen. He put on the coffee pot. He was very angry. He was also very worried.

PART TWO: DISCOVERIES

At seven a.m. Mrs. Ryan was in curlers. She was quite embarrassed when a Super Swift pulled up by her house and a Policeman came to the door.

“Where’s the boy?” he asked, grinning. Mrs. Ryan said she thought he was at classes. She was punched in the face. He stood over her, quivering, his shaved head glistening in the morning sun that radiated innocently through the living room curtains. He pointed a revolver at her temple.

“Where is he?” He almost screamed it.

But, far off, Eric could hear little more than the gentle cries of birds, echoing fondly to each other and all those listening, little more than the Yamaha Enduro’s cheerful mid-morning babble. He could see little more than Mr. Hendricks easing the bike into a series of curves on a homemade track behind the house. Little more than the, green fresh maples that enveloped the building and track like a loving mother. He could feel little else than Miranda, close beside him, and a growing awareness of freedom, freedom from anxiety. Freedom to smile. Which he did.

A Super Swift was blasting down the highway, south; a Policeman in the back, bent over the sink, cursed. Blood was splattered on his face and shirt.

“Em telling you,” he said, “she sure burst. I must have hit a vein.” He swathed his face. The driver sneered. The man in the gun cockpit laughed.

Mr. Hendricks sighed.

“He’s a natural,” he said. “He may make it. ”

Eric flew into a fast bend, gearing down from fourth to third, came out full throttle, watched the tachometer soaring up from five grand and sinking deep into the red...

“He may, ’’said Miranda.

The right foot peg scraped. The 250 shuddered. Eric slammed down to third again...

“Yeah, but not with the Enduro,” said Mr. Hendricks.

Eric felt it, the wind, the warmth, the feeling, the need and the ability to satisfy the need. The power. The strength. This is it, Father, this is it. The Freedom. That’s why they took it from you, Father. It’s too good. It’s an attack on them, a menace, something they can’t really comprehend.

Something they can’t compute.

A kinship with nature, a sense of manhood, of God. And they can’t have that, can they? So you can’t have it either.

Mr. Hendricks went into the house. Miranda motioned Eric to stop.

“We’ve many things to show you,” she said. “Did you know that Dad was once a cop?”

The man in the gun cockpit was sweating. It was so bloody hot. These Super Swifts were always so bloody hot. Except maybe in winter. Then you froze. He jerked absentmindedly at the magazine.

“What if we don’t find that guy?” he asked.

“Why don’t you shut up?” answered the driver. “What’s eating you anyway?”

The gunner uttered a soft, almost caressing obscenity.

The other Policeman, the one with the dirty shirt, was lying on the cot, waiting for the coffee to boil.

“I know what’s eating him, Schneider. It’s his old lady. Pretty cold, ain’t she, boy?”

The gunner wished he had a shiv.

“It’s only that I’m worried, is all,” he said. “Just got a hunch. Like maybe we aren’t gonna catch that guy.”

“We’ll catch him,” said Schneider. He was sneering. The gunner always hated it when he sneered.

Eric and Miranda were down in Mr. Hendricks’ library. Libraries weren’t rare. This one was: One book said that Shakespeare was born in England. Eric couldn’t believe it. He had been taught that Shakespeare was born in Dallas in 1943. He never had liked Shakespeare much anyway. He always was possessed by the glorious atom-bombing of Hanoi. How communist babies had turned red like boiled lobsters. How the 101st Airborne had obliterated Canada’s parliamentary buildings when five Socialists were elected to serve in Ottawa.

“This isn’t the Shakespeare you know, Eric, ” Miranda was saying when Mr. Hendricks walked into the room.

“No, not quite,” he said. “Let me tell you something about the United States. It wasn’t always like this. Not so many years ago, people loved the police. Well, you know, there was respect but no fear. Everyone knew the neighborhood cop. A sort of officer-Sam-down-thestreet thing. We protected folks. We helped them out. We were on their side and they knew it. ”

Mr. Hendricks sat down on the floor, followed by Eric and Miranda. He glanced at his watch. It was past noon and he’d have to make it quick.

“Anyway that was until the late ’60s and early ’70s. That’s when the image changed. Yeah. Blacks rioted and there was a lot of trouble with something called the New Left. A lot of trouble. There was this big mess at a convention. I don’t remember where or when. It isn’t important. But the thing is, all of a sudden the press was against us. The next year there were more riots. And more. And cops busted more skulls. It appeared as if America had done herself in. The world forgot the good America had done. They wanted her blood. ”

Mr. Hendricks was sweating. He lit an illegal cigarette. He wasn’t going to let anything worry him.

The gunner was humming a tune. He tapped it out on the butt of his machine gun. Overhead, a jet coursed its way east, filtering in and out of clouds. He swiveled the turret around and up.

“Bratatatat,” he said. The plane went down, deep into the layers of his mind.

Schneider asked Paulson for some coffee, but Paulson had the headset on and couldn’t hear him. Schneider called up to the gunner.

“Hey, Smythe, you remember Hendricks?”

“I remember,” replied the gunner. His left hand twitched.

“He lives around here,” said Schneider. He paused. “He’s got a sweet chick of a daughter, Smythe.”

Smythe licked his lips, nervously.

“Who’s that?” asked Paulson.

“So finally,” continued Mr. Hendricks, “it got so bad that five presidents were assassinated in the space of less than a year. That was the end of the individual. The police protected the state from the people. The average Joe was fair game. If he’s suspicious, shoot him. Only that’s messy. So blacklist him. If he’s different, destroy him, or his means of being different. Such as his motorcycle. ”

Mr. Hendricks spat on the floor.

“Come outside, Eric, ” he said. “I have something to show you. ”

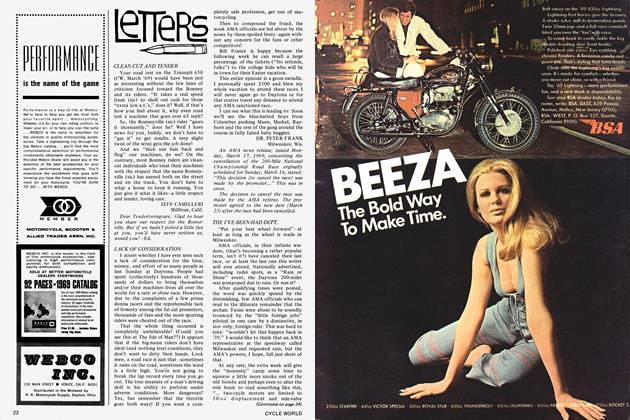

It was the color of a smoking orange moon, the final eruption of the Earth, the death gasp of the sun and it had a scoop that embraced the gas tank, clipons, engine, transmission and frame like a furnace hand. Eric felt it might have something to do with streamlining. It was a production racer and it went like hell and the Police had never found it.

It had taken Mr. Hendricks so long. Years. A three-cylinder Kawasaki 500. So fast, so very fast. So much of a realization, so much of a beautiful and tragic dream. It had taken months to break it in. One night a week. Now, in all likelihood, it would soon be on the highway, asunder, a Super Swift roaring over what was left of it, and Eric, poor stupid kid, lying in the middle of the road trying to get one gulp of dark night air into his broken body and the Super Swift bearing down, firing, perforating the asphalt and Eric trying to get up...

He watched Eric sprint the Kawasaki with incredible quickness into a fast hard ess and knew exactly how he felt. He closed his eyes. Gently, lovingly, he swept past a Norton, dreamlike and soft, at Daytona. No, no, he shook his head, not Daytona, the Isle of Man, yes...

The Isle of Man.

Smythe opened the hatch on the plexiglass turret. It never failed. These forests and dirt roads always made him feel as if he were suffocating. He needed air. There was something dangerous about a lot of trees. You couldn’t see all you wanted to see. The trees weren’t orderly and each was' different. They

were after him, they would kill him. They wanted to. He ran a hand down his face. He wished Schneider would slow down. Dirt roads weren’t safe. There was no one else around. They didn’t know exactly where Hendricks lived. What if the Super Swift crashed? He didn’t want to spend a blind night with all those filthy trees. At least he could hear.

And he heard a sound that ran through his body like electric blood.

“Stop the car,” he said.

Schneider only growled. He hated stopping. He accelerated.

“Will you stop the car?”

Silence. Paulson was stifling a giggle on the cot.

“Stop the car!” The gunner was yelling, kicking the inside of the turret with his foot.

Schnieder hit the brakes. The Super Swift drifted sideways down the road. Smythe nearly screamed as the trees flew by in a green blur. Paulson fell off the cot and rolled on the floor, laughing.

“What do you want?’’ asked Schneider.

“I’m not telling.” Why don’t they leave me alone?

Schneider turned around slowly and looked at the gunner. His eyes were popped wide and he was pale. Like a vampire with a stake in his heart, thought Smythe.

“I thought I heard one of those motor-things,” he whispered.

Paulson quit laughing. An obscene drool fell from his cadaverous, open mouth and settled onto his shirt collar.

Miranda sat on the porch watching Eric on the track, and watching her father watching Eric. She wondered how far he would get. Her father had told him he must leave at midnight when the curfew was in effect and roads were clear of commuters. He would ride about 150 miles on secondary roads that he had outlined on a map. Then he must break on through to the freeway, where he must outrun every Super Swift from there to the border. That was another 50 or so miles. He didn’t have a hope. Nobody did.

He wasn ’t like the others, she thought. He didn’t like uniforms and loud voices and orders. And beer, cars, or weekend meetings. He couldn’t understand why he couldn’t be happy in a world where you had all you needed, providing you did and felt as others thought you should. The sun, alive and warm, slipped, golden, behind a dark, shaded mountain. You couldn’t tell anyone how you felt. Not even Eric. It wasn’t done. The foulest word she could think of flowed softly, like water, from her mouth.

It was a sigh.

A final protest.

Ah, thought Eric, she sure looks good in jeans.

Schneider held the field glasses to his eyes, which were moist and strained, and peered from the edge of the maple trees onto the track, where Eric was refueling the Kawasaki, to Miranda on the porch, where his vision rested for a while, and, finally, to Mr. Hendricks.

They always shot you in the back of the neck, thought Mr. Hendricks, vaguely. That’s what Orwell said.

“Get him,” said Schneider.

Smythe clipped a magazine into his Browning. He was breathing hard. It was all these trees. Ants an’ bugs an’ leaves an’ stuff. It’s getting all dark. Spooky, is what it is.

Feeling better now. Going to blow your face off. Feeling better...

He lowered the sights, released the safety—this is too good—he guided his finger to the trigger, which was soft and yielding—feels so good—Mr. Hendricks’ neck bulged into the telescopic sights-I love you, so warm, I love you, so pretty, I love you, ah don’t leave me, it’ll last forever, I love you, you know I do, yes...

Mr. Hendricks went down, screaming.

Miranda uttered a small cry. She knew it would happen some day. She glanced at her father, gyrating in the grass, and at Eric, who already had started the bike and was moving off the track at full throttle and onto the road leading to the woods. No tears of grief flooded her eyes. Only one feeling came to her. Fear. Only one thought occurred. To run. So she hurtled over the porch railing and ran. And Smythe kept on firing and Miranda kept on running.

PART THREE: THE LONG RUN

It must have been 10 o’clock by now. Eric’s watch had been smashed in the escape and his wrist was bleeding lightly. Probably a bullet, he thought. He brought his wrist up to his mouth and sucked.

He had ridden the bike down the road and had pulled into the forest. The Super Swift had passed by, perhaps two hours ago. He couldn’t see if Miranda was in it. All he saw was the gunner in his illuminated turret, smiling.

She must be dead. Maybe they had hung her up by her feet like a deer?

God, I’m sorry.

When the crescent moon continued its lonely flight across the stars, at midnight, when night died and day was reborn, Eric would make his long run. It was a form of redemption. Of penance.

Of moon and stars, thought Miranda. Loneliness is the cold, dark breath between Neptune and Pluto. She slept somewhere among the maples and Eric, somewhere, waited.

“You think they’ll forget about Ryan, huh?” asked Paulson.

“Yeah,” said Schneider, “well, listen. We got ourselves one, already. Stiff, mind you.”

Smythe laughed because, sure enough, Mr. Hendricks was all stiffed up, all right.

“And,” continued Schneider, “that guy with the bike has got to make a break for the border, now don’t he? Well, we’ll be waiting, maybe 10 miles out of Blaine. Okay? Sure they’ll forget. We have ourselves a cigaretter and a motorcycler all in one night. Who will care about that Ryan kid? Neat, eh?”

“Yeah, neat,” said Smythe.

“Neat,” said Paulson. “You know, we don’t get along so bad after all. You know?”

“Bratatatat,” said Smythe.

They all laughed clearly and goodnaturedly. This would be a night to remember.

Eric wheeled the Kawasaki from the trees onto the road. He would have about a five-mile ride to the freeway; then he must make a quick dash across it onto another secondary rural road, as he had done one short night ago. He plunged his leg up and down like a piston three times, and the bike cracked to life. He pulled in the clutch, and his left foot reached for first, connected, and he eased on the gas and the clutch was let out and the gears engaged, and Eric rode into the night. It was dark.

Eric, at the crossroads between dirt and asphalt, looked up and down. The freeway beckoned North. This, thought Eric, was the challenge. The challenge of life versus death. But it musn’t be met now. Not yet.

The Kawasaki edged slowly across the open and vunerable freeway and onto the road. It was a moment of exposure, and Eric had been tense and unprotected. Now he was hidden and could relax and breathe full and long. He placed the bike in third and cruised in the dirt, passing empty and sleeping farm houses. Most folks had long since left the countryside to live in Seattle, where tall building evoked no feelings beyond themselves. The buildings were there, they existed, and that was it. That was all that mattered. There could be little chance of arousing an irate farmer with a ready ear for motorcycles.

Occasionally, across the fields Eric could see a pair of headlights moving down the freeway, distant, fast and probing. As he leaned the bike in and out of sharp, rough corners, he continued to fire glances behind him. Each time he half expected to see a Super Swift’s lights feeling like blind tentacles around a turn. But he didn’t. The Kawasaki had no headlamp buried in its fairing. He could see them, but they couldn’t see him.

The road now changed to worn asphalt. Eric knew he must be nearing a town. Cattle along the roadside raised their sleep-leaden heads from the cool grass and made silent inquiries with their eyes.

Neither Eric nor the bike could make replies. They were merely enjoying the ride.

It was, indeed, a very small town. The store neons glittered a welcome, though usually at this time there were none to see them save petty thieves, the Police, and 13-year-olds with a taste for adventure.

Tonight, it was different.

Eric let the bike die. There was no point in making more noise than necessary. He pushed the bike into an Eagle gas station. The Eagle erupted on and off into blue and yellow light. Eric tapped the spring-action gas cap and it snapped open. There was no reason for the gas pump to be locked, for none but the very foolish, or the very desperate, would dare steal gasoline during the curfew hours. The tank was filled. He figured he had perhaps another 90 miles to the border and about 40 miles to the freeway.

He lit up a cigarette Mr. Hendricks had given him. He was careful not to inhale.

This is what it must have been like. He let his imagination creep up from the bottom of his mind, where it had remained stagnant too long, and roll out from his eyes like mist.

He could see himself pulling into the station. The sun would be oppressively and wonderfully hot and dry. It would be two o’clock in the afternoon and Miranda would be on the back.

“Sure is a pretty bike, ” would say the attendant.

“And it’s fast too. ”

“Sure is pretty. ”

“Almost as pretty as you,” Eric would say, laughingly, turning to Miranda. She would smile. Then he would pay the attendant, who would be young and happily envious, and say good afternoon...

Eric threw down the cigarette and slapped the cap back on. He started running the Kawasaki, which was, nonetheless, very pretty, down the street and out of town.

Eric rode on, cascading down a long, curving road edged on both sides with tall, gray cottonwoods. Not far off, in the moonlight, he could see the freeway, a lifeless strip like a sullen and dangerous finger reaching its way toward Blaine.

The men in the Super Swift weren’t saying much. They had pulled off the freeway 11 miles from the Canadian border and were waiting. Schneider and Paulson were gazing out the front window and were breathing very quietly, the round fog from their breath hazing the glass. Smythe was squatting, froglike, on the roof, leaving the turret hatch open so he could be ready almost instantly.

The engine was running, like an old washing machine. Six o’clock Monday morning. Lulling.

They were waiting.

The sign read:

38 Miles to Blaine (If crossing into Canada, have authorization slip ready)

Very few Americans were allowed to cross into Canada. Usually, only high ranking businessmen. The U.S. owned 100 percent of Canada’s industry.

The border would be open. Even now. It was a form of flaunt.

Eric hit first gear up for all it was worth, then flashed through second, third, fourth and finally high into fifth. This, then, was the challenge, met.

The dotted line went on and by forever. Eric’s eyes issued streams of tears from the wind, which had suddenly turned like ice. He reached for the goggles. The lenses were shooting out like a bizarre banner from behind his neck. The fingers of his left hand slipped in their grasp of the strap. The bike weaved across the line, crazily. He saw six white lines, then five, then seven. The rear wheel careened into the shoulder. Eric released the throttle and touched the brakes. The bike shifted down to fourth, then third. Now there were two lines. Now one. He placed the goggles securely around his eyes, crouched on the tank, looked behind him and cranked the limit out of third.

Among leaves and outhouses, cows and fences, an irate farmer awoke and wondered what on earth was making that horrible wail. Memories of all the kittens he had drowned came back to him. He shivered, then fell back to sleep, the blankets molded around him like a warm, cozy sock.

Eric moved on, each long mile rocketing by in a matter of seconds.

I might, he thought, make it.

He pressed himself harder down onto the immense orange tank and gave it just a bit more throttle.

Smythe was getting excited.

Wait! Listen. Be sure now, no false alarms. Listen...yes...yes!

He jutted his head like a mad squirrel into the turret.

“He’s coming! I hear him—listen. He’s coming!”

“Hot diggety!” said Paulson and felt a trifle foolish.

Schneider piloted the Super Swift onto the freeway and rushed through the gears. He left the lights out, and although he could see well enough to stay on the road, he locked the steering mechanism into Freeway-Straight position. Only one light illuminated the dash. It was green and trickled, weakly, from under the speedometer. It read 127 mph. Not bad.

(Continued on page 121)

Continued from page 78

Smythe swiveled the twin machine guns to face the motorcyclist when he came up behind them. He didn’t know how fast the things went. He sure hoped it could catch up.

Paulson stepped briskly over Mr. Hendricks and opened the hydraulically assisted rear doors. He unlatched the overhanging spotlight from the ceiling and swung it out into the open air. He placed a finger on the switch and asked if they were ready and they said that they were.

Eric suddenly wished he had a headlight. He could, now, barely discern the outline of a Super Swift perhaps 100 yards ahead of him.

He didn’t know what to do.

They must have heard the bike miles off, he thought. Miles and miles. I’ve had enough. No.

He realized that his body was shivering with cold. He couldn’t get any air, couldn’t breathe.

Paulson flicked the switch.

His eyes ached. He couldn’t see.

Help me.

“Now we got you! Now we got you!” Eric dropped into fourth, momentarily, and the bike surged further into the violent fit of light.

Please.

The machine guns unleashed florescent bars of orange, which vanished, then reappeared, and seemed to encircle him like a shifting, red-hot cage.

I will not give up. I refuse to die. I refuse.

Then, the light was gone.

PART FOUR: REALIZATION

Paulson was incredulous.

“He passed us...”

Schneider turned on the headlights. The Kawasaki was slamming down the road far ahead. Soon it faded beyond the reach of headlight or bullet. Schneider stopped the car. He turned back to look at the other two. He was tight lipped and livid. Paulson looked at him for an instant, then found that his shoes had somehow lost their glimmer. Smythe stared at and through, not knowing which, the distorted plexiglass turret.

Someone had plucked a lemon lollipop from his mouth and he was rather upset about it.

Eric slashed the bike through the streets of Blaine. The U.S. Customs rose ahead. Eric was through the wide open gate before the Border Official had time to put down his Reader’s Digest. He bolted from his chair and ran to the radio, swearing.

One down, one to go.

The Kawasaki stormed ferociously through—North.

Didn’t see nothing, thought the man on the other side.

Eric let out a terrific whoop.

Didn’t hear nothing, neither.

Eric rode into a drive-in cafe. A huge black and yellow sign read “Eat. ” There were a lot of cars parked outside. He ordered a coffee and paid the cashier.

“American, eh?”asked the cashier.

He took the coffee to the bike and sat sideways on the seat. He was exhausted.

The War is over.

He sipped the coffee. It was hot. He didn’t notice the hand on his shoulder until it applied a bit more pressure.

“Where’s your license plate, son? And your lights?” It was Mountie. Only a Mountie.

The War is over. It is.

“Just, ’’said Eric, “made the run from Seattle. ”

“Seattle!” said the officer. Amazing. “Pretty rough, I’ll bet?”

The War is not over.

“I left something behind.” Eric kicked the bike over. He put the goggles over his eyes.

The officer watched Eric gain speed through the Canadian border and by the time he blazed into Washington State he was in fifth. He counted the gears. Five.

I never, thought the officer, out loud, seen such a fool in my entire life. ¡Oj

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Round Up

June 1969 By Joe Parkhurst -

The Scene

June 1969 By Ivan J. Wagar -

The Service Department

June 1969 By John Dunn -

Letters

LettersLetters

June 1969 -

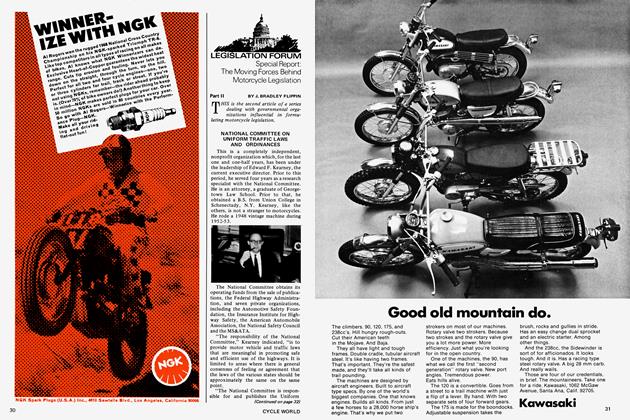

Legislation Forum

Legislation ForumSpecial Report: the Moving Forces Behind Motorcycle Legislation

June 1969 By J. Bradley Flippin -

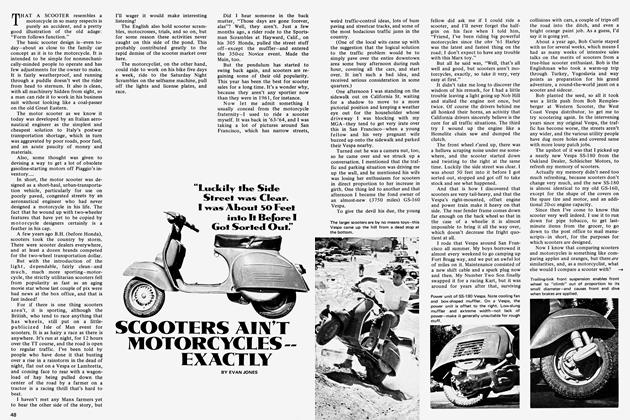

Offshoot Dept.

Offshoot Dept.Scooters Ain't Motorcycles-- Exactly

June 1969 By Evan Jones