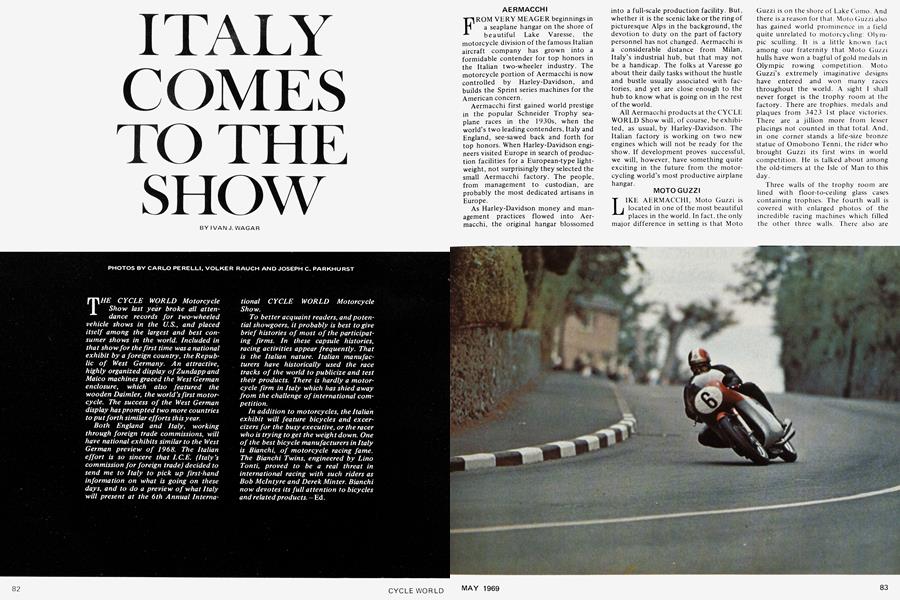

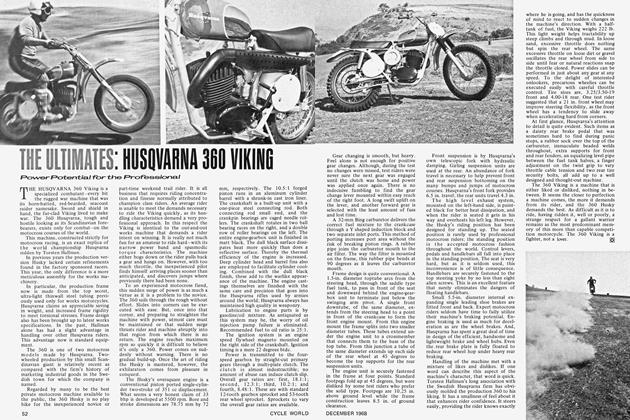

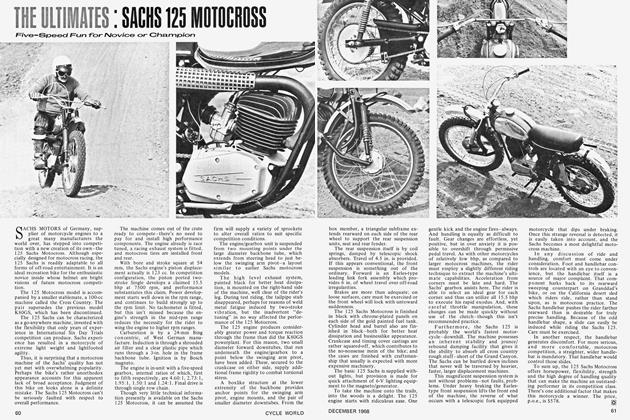

ITALY COMES TO THE SHOW

IVAN J. WAGAR

THE CYCLE WORLD Motorcycle Show last year broke a11 atten dance records for two-wheeled vehicle shows in the U.S., and placed itself among the largest and best consumer shows in the world. Included in that show for the first time was a national exhibit by a foreign country, the Republie of West Germany. An attractive, highly organized display of Zundapp and Maico machines graced the West German enclosure, which also featured the wooden Daimler, the world's first motorcycle. The success of the West German display has prompted two more countries to put forth similar efforts this year.

Both England and Italy, working

through foreign trade commissions, will

have national exhibits similar to the West

German preview of 1968. The Italian

effort is so sincere that I.C.E. (Italy's

commission for foreign trade) decided to

send me to Italy to pick up first-hand

information on what is going on these

days, and to do a preview of what Italy

will present at the 6 th Annual Interna-

tional CYCLE WORLD Motorcycle

Show.

To better acquaint readers, and poten-

tial showgoers, it probably is best to give

brief histories of most of the participat-

ing firms. In these capsule histories,

racing activities appear frequently. That

is the Italian nature. Italian manu facturers have historically used the race

tracks of the world to publicize and test

their products. There is hardly a motor-

cycle firm in Italy which has shied away

from the challenge of international corn-

petition.

In addition to motorcycles, the Italian

exhibit will feature bicycles and ex cer-

cizers for the busy executive, or the racer

who is trying to get the weight down. One

of the best bicycle manufacturers in Italy

is Bianchi, of motorcycle racing fame,

The Bianchi Twins, engineered by Lino

Tonti, proved to be a real threat in

international racing with such riders as

Bob McIntyre and Derek Minier. Bianchi

now devotes its full attention to bicycles

\and related products. — Ed.

AERMACCHI

FROM VERY MEAGER beginnings in a seaplane hangar on the shore of beautiful Lake Varesse, the motorcycle division of the famous Italian aircraft company has grown into a formidable contender for top honors in the Italian two-wheeler industry. The motorcycle portion of Aermacchi is now controlled by Harley-Davidson, and builds the Sprint series machines for the American concern.

Aermacchi first gained world prestige in the popular Schneider Trophy seaplane races in the 1930s, when the world’s two leading contenders, Italy and England, see-sawed back and forth for top honors. When Harley-Davidson engineers visited Europe in search of production facilities for a European-type lightweight, not surprisingly they selected the small Aermacchi factory. The people, from management to custodian, are probably the most dedicated artisans in Europe.

As Harley-Davidson money and management practices flowed into Aermacchi, the original hangar blossomed into a full-scale production facility. But, whether it is the scenic lake or the ring of picturesque Alps in the background, the devotion to duty on the part of factory personnel has not changed. Aermacchi is a considerable distance from Milan, Italy’s industrial hub, but that may not be a handicap. The folks at Varesse go about their daily tasks without the hustle and bustle usually associated with factories, and yet are close enough to the hub to know what is going on in the rest of the world.

All Aermacchi products at the CYCLE WORLD Show will, of course, be exhibited, as usual, by Harley-Davidson. The Italian factory is working on two new engines which will not be ready for the show. If development proves successful, we will, however, have something quite exciting in the future from the motorcycling world’s most productive airplane hangar.

MOTO GUZZI

LIKE AERMACCHI, Moto Guzzi is located in one of the most beautiful places in the world. In fact, the only major difference in setting is that Moto

Guzzi is on the shore of Lake Como. And there isa reason for that. Moto Guzzi also has gained world prominence in a field quite unrelated to motorcycling: Olympic sculling. It is a little known fact among our fraternity that Moto Guzzi hulls have won a bagful of gold medals in Olympic rowing competition. Moto Guzzi’s extremely imaginative designs have entered and won many races throughout the world. A sight I shall never forget is the trophy room at the factory. There are trophies, medals and plaques from 3423 1st place victories. There are a jillion more from lesser placings not counted in that total. And, in one corner stands a life-size bronze statue of Omobono Tenni, the rider who brought Guzzi its first wins in world competition. He is talked about among the old-timers at the Isle of Man to this day.

Three walls of the trophy room are lined with floor-to-ceiling glass cases containing trophies. The fourth wall is covered with enlarged photos of the incredible racing machines which filled the other three walls. There also are photos of the riders who helped Moto Guzzi win so many victories. In the history of motorcycle racing, there are very few factories which compare with Moto Guzzi in the amount of respect shown to the rider.

But now the racing days are gone. Like most other Italian firms, Moto Guzzi ended its racing projects in 1 957. Unlike some of the others, Guzzi has not made a comeback to international racing. Instead they have concentrated on the development of the very successful V7 touring machine, along with several attractive lightweight models for the sporting market and export. Competition these days is limited to ISDT forms of racing and trials, where Moto Guzzi has picked up more than its share of silver and gold medals.

Guzzi’s future? It is a sure bet that Moto Guzzi will be around for many years to come. The grand and glorious years of grand prix racing are gone, but present management, (and the fact that Lino Tonti is now on the payroll) should introduce more big ideas for the American market.

INNOCENTI

MOST MOTORCYCLISTS look down~on scooters, viewing them as a mode of transport for old ladies. ButI have seen world champion~ ship motocross riders, plus some very famous road racers, jump on a scooter and suddenly realize what they have been missing. A scooter is comfortable, clean, easy to handle and easy to park—all features that a hundred thousand business executives in this country could appreciate, if they had the chance.

As Italy becomes more affluent, the masses are giving up two-wheelers for automobiles, and Innocenti is rapidly becoming a major producer of English BMC cars, which are being built under license. In addition to Minis, 1100s and Lambretta scooters, Innocenti also builds gigantic presses and machine tools for heavy industry. The trophy room at Lambretta proves that even a scooter manufacturer in Italy is interested in racing and records at one time or another. Resting in the corner of the room is the beautiful little Lambretta prototype grand prix racer. Built in 1950, the 250-cc transverse V-twin never was raced because of a management decision to maintain the scooter image. Even now, 20 years later, the machine would be a credit to any racing department.

A MOTORCYCLING PARADISE

DUCATI

THE DUCATI factory, more than most others, has its sights on the American market. The entire model line, especially the new 450 cc, is tailored for the U.S. buyer. In enormous buildings, far larger than needed, Ducati is doing a booming business in small auxilliary engines, both twoand four stroke models. Despite the success in this new field, Ducati still places motorcycle production above all other efforts.

Ducati’s racing activity has been shifted to the Spanish branch. A visit to the Bologna plant reveals nothing concerning the existence of the four-cylinder, or very fast Desmo Twins. In fact, the parent company has no racing programs whatever underway.

PIAGGIO

TALY FACED many problems after World War II. Not only was the country a shambles, but public transport was virtually nonexistent. The man to come to the aid of the masses was Enrico Piaggio, builder of airplanes and aircraft engines during the war. Piaggio realized the economy was not ready for a car, even the lowest cost design possible, so he put his efforts into a two-wheeled vehicle. Besides the cost advantage, a two-wheeler could more easily negotiate the badly damaged roads.

Within a year, Piaggio and his design team saw the birth of the motor scooter. The Vespa was a first in many ways. The streamlined monocoque configuration eliminated the need for a frame. The completely enclosed drive reduced maintenance, and the pleasing appearance, coupled with good rider protection, soon brought buyers by the thousands. By 1958 Piaggio had produced 1,000,000 Vespas in Italy. There is, in fact, one Vespa for every 52 people in Italy. This figure does not count the Vespas being built under license in Spain, India, Formosa, Indonesia, Malaysia and Israel.

Piaggio’s interest in competition followed the typical Italian pattern. And, it isa little known fact that 9 of 10 Vespas entered in the 1951 International Six Days Trial came home with gold medals. During the same year, the little Vespa 125-cc “Flying Cigar” streamliner covered the flying kilometer at 106 mph. The water-cooled engine produced 18 bhp at 9500 rpm, three more horsepower than the dohc Mondial grand prix racers of the same year.

A business merger with Fiat, plus the death of the brilliant Enrico Piaggio in 1965, brought an end to competition efforts. Under the guidance of Vittorio Casini, the experimental department concentrates its full attention on development of nine Vespa models, which range from 50 to 180 cc, with such up-to-date features as automatic oil injection.

GILERA

IN 1 909, 22-year-old Giuseppe Gilera founded Italy's first motorcycle factory, after starting his appren ticeship in bicycle factories at the age of 1 5. The young Güera quickly established himself as an engineering genius, as well as an active sporting rider. It was Giuseppe who rode his own machine to Gilera’s first race win, in 1912, at the Cremona endurance classic—a distance of 1 17 miles— at the then remarkable speed of 28 mph. A younger brother, Luigi, became hooked on sidecar racing and kept the family flag flying into the 1940s.

The founder gave up active competition during World War I, and concentrated on production of the sturdy sidevalve Güera engines. In 1930 and 1931, Güera won the Trophy award at the International Six Days Priai, to become internationally famous, and prosperity increased at a goodly rate. The factory, situated at Arcore, close to Monza, was keeping pace with Italy’s overall motorcycle industry growth, and began to show an interest in grand prix racing.

Early in 1936, Giuseppe bought the rights to produce the Swallow, a fourcylinder 500-cc racing engine. It was, to say the least, the most futuristic engine in existence. One of the lead designers of the Swallow was Piero Taruffi, destined to become one of Italy’s most famous names in racing. The Swallow engine featured such things as supercharging, which the FIM permitted at the time, and water cooling. Considering the metallurgy of that period, it took considerable courage on the part of Giuseppe to have the foresight to enter into such a program. With only slight development, the engine was putting out 80 bhp at 8800 rpm, and it became apparent very quickly that engine progress far exceeded chassis technology, for it was virtually impossible to keep the thing on the road. It is quite amazing that Güera left the engine alone and concentrated completely on frame development, and still managed to set a world record of 1 70.5 mph in 1937, with Taruffi riding. By 1939 Enrico Serafini had won the European Championship with a “stock” engine, but by this time the chassis had been pretty much sorted out. 1'hen World War 11, the plague of racing, halted the screeching Güera.

After the war, the FIM made a rule change banning superchargers and tuel. Pump gasoline at the time was somewhere around 70 octane, a diet completely unsatisfactory for the Güera engine. To comply with the new rules, the blower was removed and the redesigned engine was converted to air cooling. As development continued, the octane rating of pump gasoline increased, and by 1948 the Güera was on its way again. With the help of riders such as Masetti, Pagani. Liberati, Milani, Geoff Duke, Reg Armstrong and Bob McIntyre, Güera won 10 world championships, and set numerous world speed records.

And what a power increase Güera picked up during that 10-year period! When supercharging and fuel were dropped, power decreased from 80 bhp to a measly 5 2 bhp at 8500 rpm. But, by 1 957, the 500 was churning out 72 bhp at 10,500 rpm. The 350 was capable of 49 bhp at 1 1,000 rpm.

ITALY

The year 1957 will always be remembered as a very bad year for international racing. Gilera, Moto Guzzi and Mondial all agreed to quit racing. Thus, once more, the Gilera Fours were shelved. Gilera did make a half-hearted comeback in 1963, but it was with the same 1957 equipment, with new rear dampers and up-to-date tires being about the only modifications. Considering the machines had no development for almost six years, it is surprising how well John Hartle and Phil Read did under the Scuderia Duke sponsorship.

When Gilera officially retired from grand prix racing in 1957, the factory returned to its first love—international trials competition-and brought home the Silver Vase from the ISDT in 1960. Last year’s ISDT brought more prestige to Gilera; two of the Italian team were mounted on Güeras.

RACI NG, FFHE NATIONAL SPORT

The Gilera factory is now concentrating on development of the new 500-cc ohc Twin, an attractive five-speed road burner, and a 125-cc rotary valve two-stroke, the first non-four-stroke ever produced by Italy’s oldest motorcycle factory. At age 70, Giuseppe Gilera is retired from the company he founded. He will, however, always be respected as the man who put as much into racing as he took from it.

AGRATI-GARELLI

ADALBERTO GARELLI built his L first motorcycle in 1913. It wasa 350-cc split Single two-stroke with a short future, due to the outbreak of World War I. After the war a plant was constructed on the outskirts of Milan, and a new version, using the same basic design, went into series production. Like all other race-minded factories, Garelli turned to racing to publicize the product. In 1919, Ettore Girardi won the Milanto-Naples endurance race at an average speed of 23 mph for the 535 miles, an outstanding feat.

In 1922, with a win in the French Grand Prix, Garelli collected Italy’s first foreign classic victory. Tazio Nuvolari and Achille Varzi, of car fame, were among the top line riders to race under the Garelli banner. During the period from 1922 to 1926, the split Singles fairly dusted off the sidevalve-engined opposition.

From 1926, interest in racing gradually decreased until the 350 racer was completely discontinued in 1935. The machine had collected 200 long-distance records before its death.

After World War II, the Garelli factory made a comeback with the Mosquito, a 38-cc clip-on engine for bicycles. Millions of these little units were sold as factories in England and France poured out production to a motorized-starved Europe. In 1961, Garelli merged with Agrati, another firm specializing in moped engines, and became Italy’s largest producer of small engines.

MV AGUSTA

N0 STORY on Italian motorcycling, or international racing, would be complete without a chapter from MV Agusta. From 1945 until this issue appears on the newsstands, MV has won a total of 55 world championships—the most enviable record in the history of motorcycle racing. All of this success is due to the iron hand of the autocratic Domenico Agusta, the man who told the Italian government to go to hell in 1957. As previously stated, 1957 was a black year for racing enthusiasts. That was the year when manufacturers were asked by the government to quit racing; everyone complied, except the “Count,” as he is known in racing circles. Regardless of how he is referred to by racers, Domenico Agusta is an Italian count, and he has, like it or noty kept pace with racing technology throughout his dictatorial career.

The Count cannot, however, take full credit for the existence of MV. His father Giovanni built his first airplane in 1907, and started a company named Costruzioni Aeronautiche Giovanni Agusta. It is interesting to note at this point that the Count’s father was building airplanes two years before Italy’s first motorcycle factory was founded. During World War II, Giovanni Agusta died, leaving the company in the hands of his wife and sons. At the conclusion of hostilities, the family was presented with a new problem: What should we build? The market for airplanes was fairly small, after a war. Domenico, with very enthusiastic support from his mother, Giuseppina, and younger brothers Mario and Corrado, decided on motorcycles and changed the name of the firm to Meccanica Verghera Agusta. The introduction of Verghera isa bit strange in this story, because Verghera is a small village on the outskirts of Gallarate, home of the MV Agusta racers, and no blazing metropolis, by anyone’s standards. At least Gallarate can be found on a map, but Verghera is not in contention.

'To make a long story short, the first MV appeared in late 1945. It wasa98-cc weakling, with a two-speed gearbox. Soon it became a 1 25 three-speed, which sold in quite large numbers, much to the concern of the established firms on the scene.

Domenico Agusta was not the sort to sit around when it came time to go racing. He was, after all, producing machines at a rate to scare the big boys, so why not carry it one step further and really give them fits in racing. At Valenza, in 1946, Domenico saw his motorcycle win a race. It is a bit silly now, 23 years later, that the race was won by a 125-cc machine which put out 6 bhp, less horsepower than most 50-cc engines on the current market.

Until 1949, racing activity by MV was restricted to the 125-cc class, and with two-stroke engines. In 1950, the factory switched from the underpowered, less expensive two-strokes to an all new dohc 125 Single. Few people at the time realized the new MV racer actually was one pot of a 500-cc contender. Hardly had the 125 appeared, when three more cylinders were added to produce the unforgettable MV howl. Fewer people realized it was the beginning of an era, for Italy was gradually switching from two wheels to four. The hangers-on in the two-wheeler category were interested in prestige, and MV was gaining prestige by leaps and bounds. The Count was gaining a larger portion of the market each time an MV won a race. He continually sponsored racing, because he loved the challenge of international competition.

At some point in this story, the Count, probably by accident, became involved in the manufacture of helicopters, and money started pouring into the MV kitty. All of that aside, the Count made no bones about the fact that motorcycle racing cost 1,000.000 lire ($1,600) per day to maintain.

At this point it is logical to assume some readers will query the Count’s good judgment, or his senility. Let me assure you the Count is as crazy as a fox. For instance, he signed up Carlo Ubbiali, a most dynamic little guy, who has won nine world championships, more than any other rider. The names of riders who have taken MVs to victory are almost too numerous to mention. Would all this have been possible if Moto Guzzi and Güera had kept racing? For, not only did the absence of other factories make less competition, but it also meant the Count had first choice of the best riders in the world, and his judgment of rider ability was excellent.

As a true enthusiast, the Count did improve his machines every year, even when there did not appear to be sufficient opposition to warrant the expense. This year there will be no Hondas, and the only serious threat to MV domination comes from Benelli, but already a 500 MV Six is being readied. A Six was tried briefly in 1957 and was shelved, as MV relied on the reliable Four of that era.

While it frequently appears that the Count only stays in motorcycling to race, there have been some very attractive touring machines from Gallarate. At the present time there are street and scrambler versions of handsomely designed 1 25 and 1 50 Singles. And, making its American debut at the CYCLE WORLD Show, a new five-speed 250-cc Twin. Company officials still insist there is a strong desire to produce the 600-cc MV Four for the American market, and that one will be flown over for the show.

BEN ELLI

SIX ENGINIIRING-MINDED Be nefli brothers started a mechanical workshop in Pesaro, on the Adri atic coast, in 1911. At first, work was confined to repairs of motorcycles, cars and shotguns. Eventually the brothers started building parts for airplanes and airplane engines and, after World War 1, small two-stroke motorcycles.

It probably is inevitable that at least one of the brothers would have become a racer and, in 1923, the youngest, Tonini, made an impressive debut. Young Tonini constantly hounded his brothers to build better and faster race machines, and in 1927 Benelli produced a gear-driven 175-cc ohc engine which dominated Italian racing until 1936. By this time Benelli had grown to one of the five largest motorcycle factories in Italy.

Benelli applied racing technology in its line of sporty touring machines and developed ohc engines for 1 75, 250 and 500 road-burning Singles. Very little was done in the racing sphere from 1936 until 1938, when the factory introduced an all new dohc 250 Single, which carried the English prewar ace, Ted Mellors, to an Isle of Man win in 1939. The little Single was so successful that further development was not required, and the engineering department was free to concentrate on a four-cylinder, water-cooled, supercharged replacement. Unfortunately the war halted work on the Four and, although actually constructed, it never raced.

The Benelli factory was harder hit by the war than most. Bombed several times, the engineering department managed to survive, until the Nazis, anxious to lay their hands on the Four, tore the place to pieces and took everything in sight back to Germany. A few of the Singles had been carefully hidden, but it is interesting that the German NSU Singles of the late 1 940 period were very similar in design to the Benelli.

When the war ended, Benelli slowly struggled back to its feet, and carefully carried out modifications to the old prewar Single. For riding chores the firm signed on the brilliant Dario Ambrosini, who won the Isle of Man TT in 1950, and went on to take the world championship as well. Unfortunately, while practicing for the French Grand Prix, in 1951, the likable little ace was killed, and Benelli, completely depressed by the loss of Ambrosini, pulled out of grand prix racing.

In 1964, Benelli decided to make a full-scale comeback with a new air-cooled dohc Four, and signed up Tarquinio Provini. Just when Provini had sorted out the teething troubles, he crashed while practicing for the 1966 Isle of Man TT. So extensive were Provini’s injuries that he retired from racing, and Benelli signed on the young, tigerish Renzo Pasolini, the present official rider for the Pesaro factory.

Despite the possibility of an FIM ruling restricting grand prix machines to two cylinders, Benelli is forging ahead with a 250 V-8. Most of the engine castings are completed, plus the crankshaft. There are delays in obtaining pieces froni suppliers, such as carburetors, but the engine should be running this year. The Italian Grand Prix in September is the target deadline.

Two of the six brothers are still alive. Tonini died in a car accident just after World War II. At about that time Giovanni and Giuseppe pulled away from the family business to form the Motobi Co. which, in 1 962, merged with Benelli. Giuseppe’s sons, Marco and Luigi, have managerial positions at Benelli, while Tonini’s sons, Paolo and Piero, are primarily concerned with management of the shotgun factory.

Benelli will be at the CYCLE WORLD Show with models from 50-cc minibikes to the new 650-cc Twin, designed especially for the American market. This colorful firm also will feature the full double cradle framed sports 250and 360-cc street scramblers.

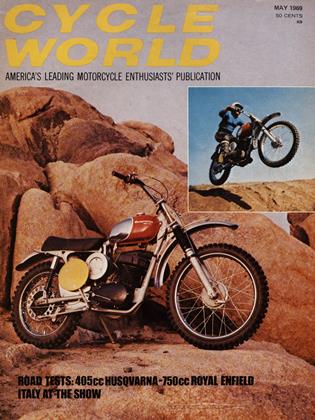

View Full Issue

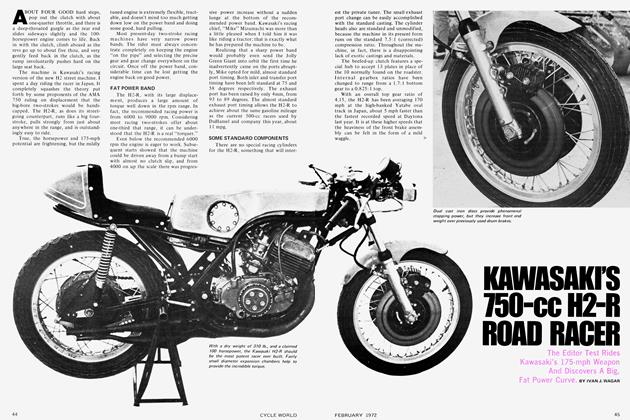

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Round Up

Round UpRound Up

May 1969 By Joe Parkhurst -

The Service Department

The Service DepartmentThe Service Department

May 1969 By John Dunn -

Letters

LettersLetters

May 1969 -

The Scene

The SceneThe Scene

May 1969 By Ivan J. Wagar -

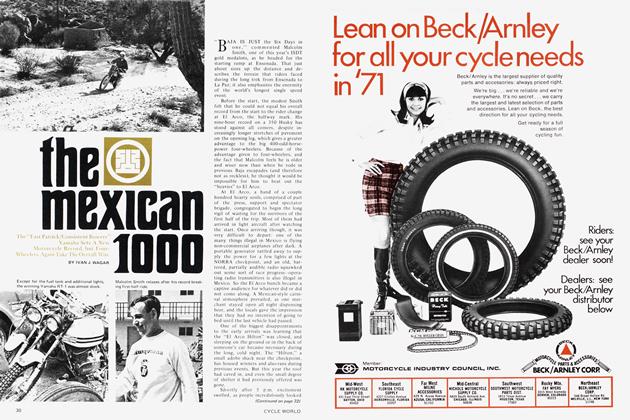

Travel

TravelSpecial Report: the Moving Forces Behind Motorcycle Legislation

May 1969 By J. Bradley Flippin -

Travel

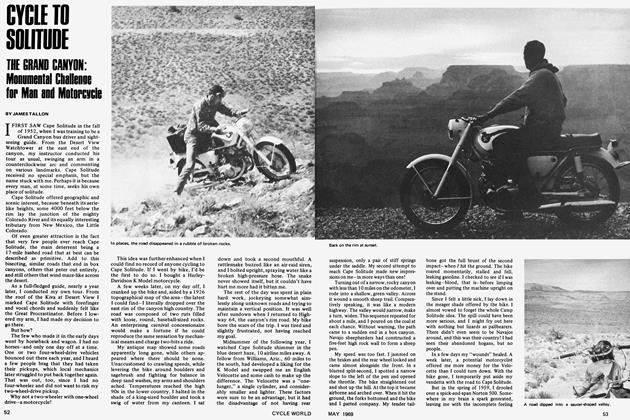

TravelCycle To Solitude

May 1969 By James Tallon