CYCLECARS

The Marriage of Motorcycles and Cars... Just Didn’t Work Out

MICHAEL LAMM

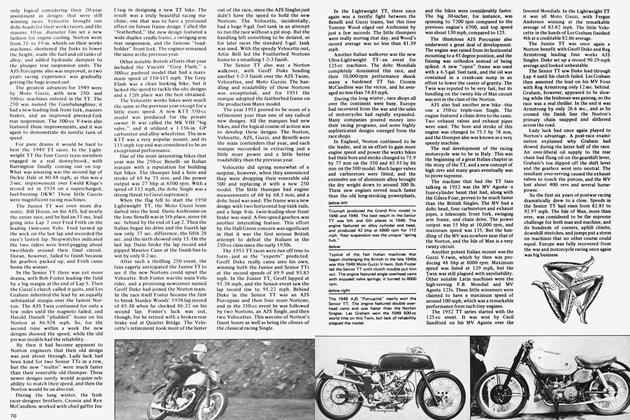

CYCLECARS became a rampant fad in this country from about 1912 through 1916. They were extremely cheap, gave an illusion of speed because of their nearness to the ground, and must have been the same sort of fun to drive as go-karts. Cyclecars tried to bridge the gap between motorcycles and conventional automobiles, usually carrying the driver and one passenger either in tandem or alongside (called “sociable”).

The majority of cyclecars were crude —some criminally so. After a short and happy life, cyclecars dropped from the American scene with such a thud that very few examples survive to this day. Partly, the reason is that most of them literally fell apart before collectors could preserve them.

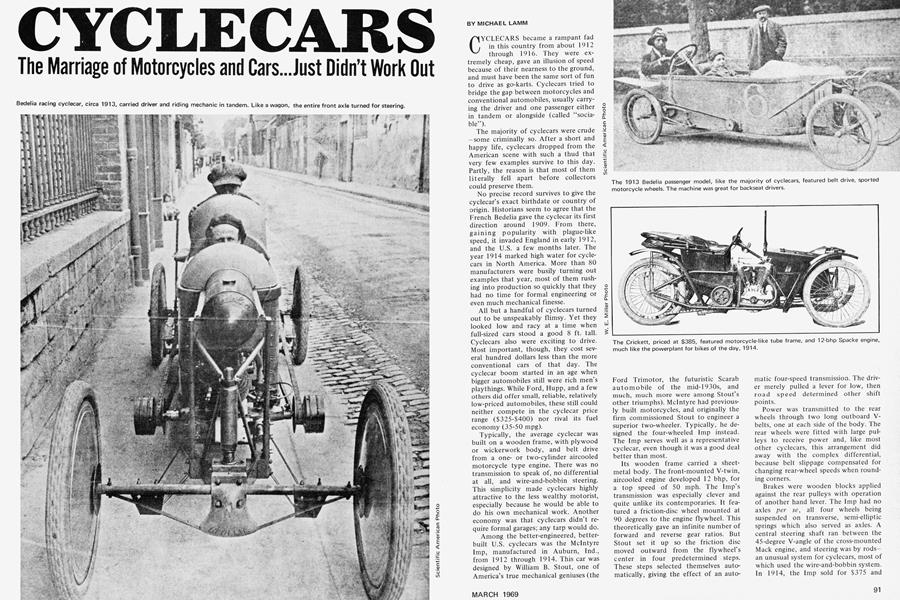

No precise record survives to give the cyclecar’s exact birthdate or country of origin. Historians seem to agree that the French Bedelía gave the cyclecar its first direction around 1909. From there, gaining popularity with plague-like speed, it invaded England in early 1912, and the U.S. a few months later. The year 1914 marked high water for cyclecars in North America. More than 80 manufacturers were busily turning out examples that year, most of them rushing into production so quickly that they had no time for formal engineering or even much mechanical finesse.

All but a handful of cyclecars turned out to be unspeakably flimsy. Yet they looked low and racy at a time when full-sized cars stood a good 8 ft. tall. Cyclecars also were exciting to drive. Most important, though, they cost several hundred dollars less than the more conventional cars of that day. The cyclecar boom started in an age when bigger automobiles still were rich men’s playthings. While Ford, Hupp, and a few others did offer small, reliable, relatively low-priced automobiles, these still could neither compete in the cyclecar price range ($325-$400) nor rival its fuel economy (35-50 mpg).

Typically, the average cyclecar was built on a wooden frame, with plywood or wickerwork body, and belt drive from a oneor two-cylinder aircooled motorcycle type engine. There was no transmission to speak of, no differential at all, and wire-and-bobbin steering. This simplicity made cyclecars highly attractive to the less wealthy motorist, especially because he would be able to do his own mechanical work. Another economy was that cyclecars didn’t require formal garages; any tarp would do.

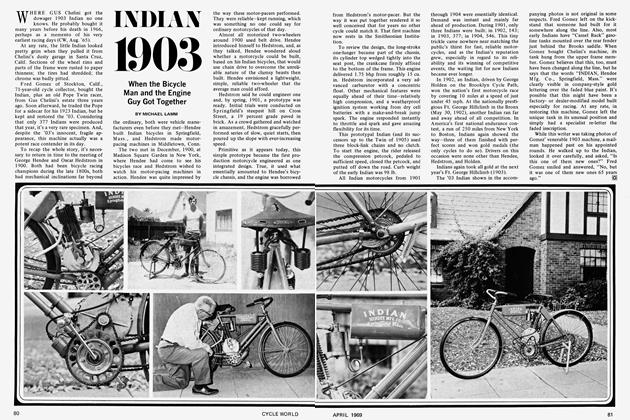

Among the better-engineered, betterbuilt U.S. cyclecars was the McIntyre Imp, manufactured in Auburn, Ind., from 1912 through 1914. This car was designed by William B. Stout, one of America’s true mechanical geniuses (the Ford Trimotor, the futuristic Scarab automobile of the mid-1930s, and much, much more were among Stout’s other triumphs). McIntyre had previously built motorcycles, and originally the firm commissioned Stout to engineer a superior two-wheeler. Typically, he designed the four-wheeled Imp instead. The Imp serves well as a representative cyclecar, even though it was a good deal better than most.

Its wooden frame carried a sheetmetal body. The front-mounted V-twin, aircooled engine developed 12 bhp, for a top speed of 50 mph. The Imp’s transmission was especially clever and quite unlike its contemporaries. It featured a friction-disc wheel mounted at 90 degrees to the engine flywheel. This theoretically gave an infinite number of forward and reverse gear ratios. But Stout set it up so the friction disc moved outward from the flywheel’s center in four predetermined steps. These steps selected themselves automatically, giving the effect of an automatic four-speed transmission. The driver merely pulled a lever for low, then road speed determined other shift points.

Power was transmitted to the rear wheels through two long outboard Vbelts, one at each side of the body. The rear wheels were fitted with large pulleys to receive power and, like most other cyclecars, this arrangement did away with the complex differential, because belt slippage compensated for changing rear-wheel speeds when rounding corners.

Brakes were wooden blocks applied against the rear pulleys with operation of another hand lever. The Imp had no axles per se, all four wheels being suspended on transverse, semi-elliptic springs which also served as axles. A central steering shaft ran between the 45-degree V-angle of the cross-mounted Mack engine, and steering was by rodsan unusual system for cyclecars, most of which used the wire-and-bobbin system. In 1914, the imp sold for $375 and weighed 450 lb., minus personnel.

That’s a portrait of one of this country’s better cyclecars. It and lesser makes proved fertile ground for drugstore cowboys and practical jokers throughout the nation. In Sarasota, Fla., during an informal cyclecar race at a county fair, drivers returned from a briefing to find all their mounts set atop the fair’s tallest exposition building.

Another favorite was to rewind the wire-and-bobbin steering. To explain how this worked, the steering column extended as far forward in most of these cars as the tie rod. To steer, steel cable was wound several times around a bobbin at the bottom of the shaft. When the driver moved the steering wheel, the cable moved the tie rod. Pranksters, though, would unhook the cable, rewind it backward, and attach the ends again to the tie rod. So when the driver hopped in and started off down the road, he soon found that in steering to the right, the car would veer left, and vice versa. Ha, ha.

A few cyclecars had so-called “hammock seats.” These were meant to save cost and weight. They consisted of a hemp mesh sling for the driver to sit in. The sling attached to the upper body sills. Commenting on this seat’s effectiveness, Prof. A. M. Low recalled (in the 1953 “BARC Yearbook”), “...my hammock seat broke and only by quickly putting my elbows over the [body] sides did I prevent my person from being ground off by the road.” Such were the thrills of cyclecarring.

A similar hazard existed in a number of rear-engined cyclecars. In these, the V-twin stood directly behind the hammock seat, completely exposed. By relaxing and leaning back a bit too far, the driver would suddenly find himself shot upright again by a hefty electrical jolt from the spark plug.

So quickly did some cyclecar manufacturers go into production that they bought up large quantities of motorcycle and bicycle wheels that attached to their hubs with screw-on caps. All these caps were right-hand threaded on both sides of the car. Thus it wasn’t uncommon for one of the left-side wheels to leave the vehicle at a most embarrassing moment. These were a few of the tarnished virtues which helped cut the cyclecar’s life short.

Another was the roads of that day. Hardly any were paved, and most were badly rutted. Cyclecars didn’t fit into the standard 56-in. ruts made by bigger cars. Most cyclecars, with their 36-in. tread, could sometimes ride the crown of the road, but sooner or later the driver would find himself with one set of wheels dropped off. Because these cars were extremely low to the ground, this usually damaged the undercarriage.

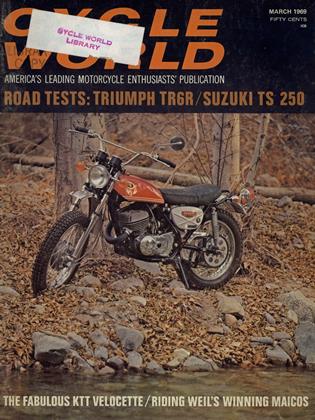

The majority of U.S. cyclecar makers favored the Spacke V-twin powerplant. This was a 70.6-cu. in., aircooled unit that developed up to 15 bhp at 2600 rpm. Among the cyclecar makes using Spacke engines were Falcon, Greyhound, Arrow, Fenton, Crickett, Scripps-Booth, and Mercury.

Drive systems varied a good deal. Some cars used full planetary transmissions, others employed centrifugal clutches, and still others used the crude but effective system of having a movable rear axle. In this type, the driver pulled a lever to slide the entire rear axle forward a few inches. In so doing, the drive belts slackened and the car could stand at rest without killing the engine.

These long belts, despite their simplicity, weren’t by any means tremendously efficient. Constant slippage soon glazed them, and even those reinforced with wire inevitably stretched after a few months. Then, too, matters weren’t helped by makes which used belts to change gears. The Bedelia had such a transmission. Here, to shift from low to high, the driver leaned out over the body side and flipped the belt from a smaller pulley onto a larger one by using a stick or wooden block. (If you think this was crude, remember that many cyclecars had no provision at all for reverse gear.)

All cyclecars had a certain undeniable cuteness, but only one or two could claim to have been genuinely “styled.” One was the Imp, which captured a certain graceful, harmonious design. Another was the J.P.L. (also known as the La Vigne), made in Detroit.

This car had an in-line, aircooled, 12-bhp Four supplied by the Henderson Motorcycle Co. The J.P.L.’s metal body was masterfully conceived, with a long hood, impressive grill, reverse-swept cowl, and a boat-tail rear taper. The body had no doors, entry being over the cut-down sides. Twin sweeps followed this contour up and over the cowl, and upholstery was diamond tufted. The whole effect was of a very sharp racing car.

The J.P.L.’s frame was spring steel, made up of two leaves that ran the entire length of the car. The chassis was underslung, with front and rear axles mounted on semi-elliptic springs. Simple, flat motorcycle fenders sheltered the large 30 by 3-in. tires. Buyers could specify various wheel diameters—40, 50, or 56 in.

Another relatively well-conceived cyclecar was the Scripps-Booth. It carried the passenger in tandem, had doors for both driver and passenger, and was one of the first motor vehicles to have a built-in trunk. This carried two or three small pieces of luggage protected from the elements inside the body rear, an advantage that not even the larger cars of that day could boast. The ScrippsBooth had a suicide front axle on quarter-elliptic springs, an arrangement that wasn’t uncommon for this type of car, many of which also had suicide rear axles (i.e., detached in front or behind the frame, the only supports being these quarter-elliptic springs).

In Europe, vehicles commonly called cyclecars often were a good deal larger and sturdier than those made in the U.S. They also were built more along big car lines. Several were powered by watercooled, four-cylinder engines, driving through sliding-gear or planetary transmission, with shaft final drive. Europeans took their cyclecars more seriously than Americans.

The French Bedelia did well in racing, as did the three-wheeled British Morgan (with JAP, Matchless or Blackburne engines) which survived virtually unchanged until 1951. Frazer-Nash, another race-bred make, began life as the sleek G.N. cyclecar. Other British cyclecars included the Enfield, Tamplin, Rollo, Eric, Sabella, Crouch, and New Hudson. Britishers, with all due respect, didn’t have quite the flair for naming cyclecars as did the Yanks. Like the Morgan, many English designs used the JAP (J. A. Prestwich) V-twin.

In addition to the Bedelia, the better -known French cyclecars included the Amilcar, Senechal, Elfe, and Aviette. In Germany, the most popular example was the three-wheeled Phanomobil.

For Europeans, the cyclecar phenomenon lasted until about 1923, after which only a handful of the once-legion makes survived. The others had either perished, reverted to motorcycles, or had grown up into full-sized cars. From time to time, wild-seed ancestors such as the post-WW II German Messerschmitt and the Spanish Biscuiter of 1957 cropped up, but while these were similar to cyclecars in size and purpose, it’s debatable whether they rated the name.

In the U.S., cyclecars had virtually ended their spurt by the time of America’s entry into World War L The American public had endured enough of most cyclecars’ lack of sophistication. Americans tended to favor conventional motorcycles on the one hand and full-sized automobiles on the other. Americans found that motorcycles could perform the same chores as cyclecars, including carrying an occasional tandem passenger (or “sociable” with a sidecar). And Model T’s had become so inexpensive that they easily rivalled the cyclecar’s initial cost. Thus the cyclecar disappeared almost as suddenly as it had come into being—and, once again, there were just cars AND motorcycles.