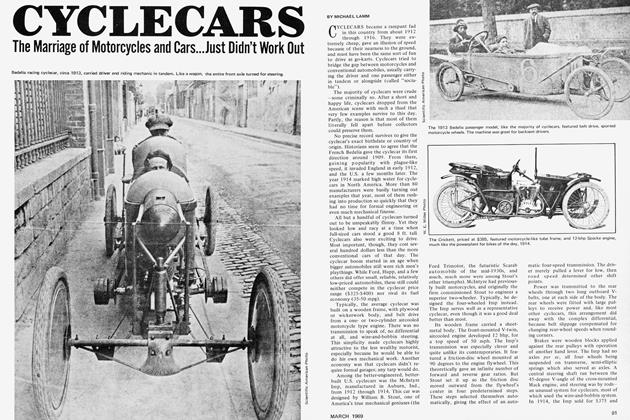

INDIAN 1903

When the Bicycle Man and the Engine Guy Got Together

MICHAEL LAMM

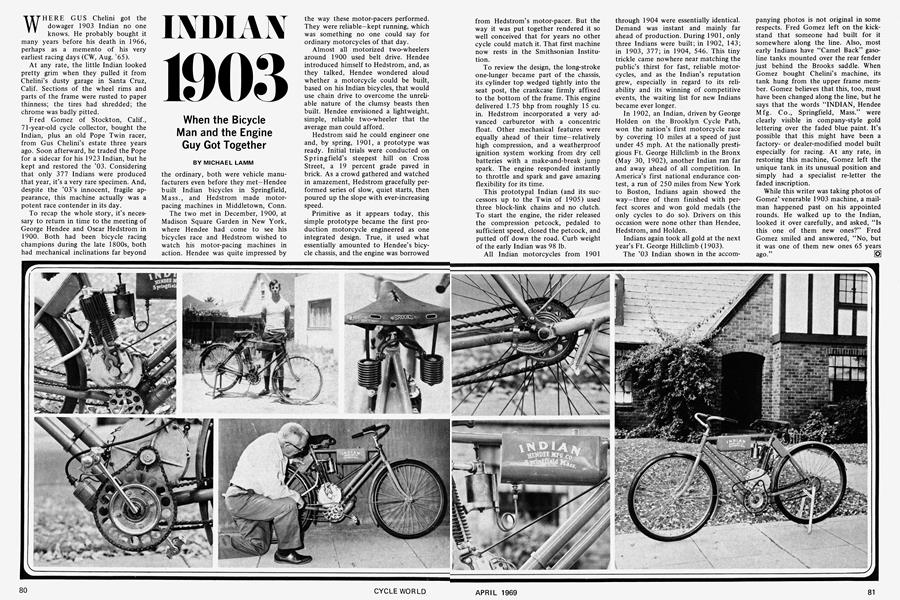

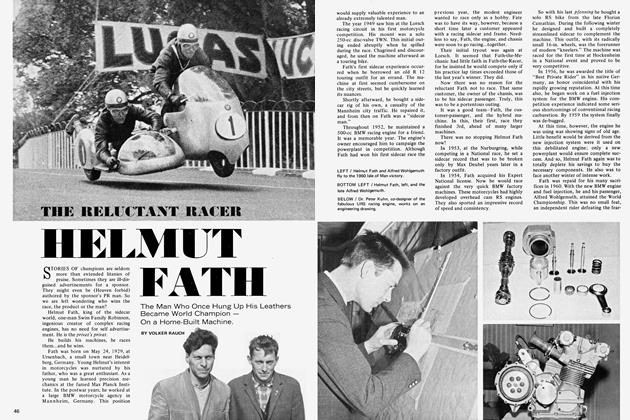

WHERE GUS Chelini got the dowager 1903 Indian no one knows. He probably bought it many years before his death in 1966, perhaps as a memento of his very earliest racing days (CW, Aug. ’65).

At any rate, the little Indian looked pretty grim when they pulled it from Chelini’s dusty garage in Santa Cruz, Calif. Sections of the wheel rims and parts of the frame were rusted to paper thinness; the tires had shredded; the chrome was badly pitted.

Fred Gomez of Stockton, Calif., 71-year-old cycle collector, bought the Indian, plus an old Pope Twin racer, from Gus Chelini’s estate three years ago. Soon afterward, he traded the Pope for a sidecar for his 1923 Indian, but he kept and restored the ’03. Considering that only 377 Indians were produced that year, it’s a very rare specimen. And, despite the ’03’s innocent, fragile appearance, this machine actually was a potent race contender in its day.

To recap the whole story, it’s necessary to return in time to the meeting of George Hendee and Oscar Hedstrom in 1900. Both had been bicycle racing champions during the late 1800s, both had mechanical inclinations far beyond the ordinary, both were vehicle manufacturers even before they met—Hendee built Indian bicycles in Springfield, Mass., and Hedstrom made motorpacing machines in Middletown, Conn.

The two met in December, 1900, at Madison Square Garden in New York, where Hendee had come to see his bicycles race and Hedstrom wished to watch his motor-pacing machines in action. Hendee was quite impressed by the way these motor-pacers performed. They were reliable—kept running, which was something no one could say for ordinary motorcycles of that day.

Almost all motorized two-wheelers around 1900 used belt drive. Hendee introduced himself to Hedstrom, and, as they talked, Hendee wondered aloud whether a motorcycle could be built, based on his Indian bicycles, that would use chain drive to overcome the unreliable nature of the clumsy beasts then built. Hendee envisioned a lightweight, simple, reliable two-wheeler that the average man could afford.

Hedstrom said he could engineer one and, by spring, 1901, a prototype was ready. Initial trials were conducted on Springfield’s steepest hill on Cross Street, a 19 percent grade paved in brick. As a crowd gathered and watched in amazement, Hedstrom gracefully performed series of slow, quiet starts, then poured up the slope with ever-increasing speed.

Primitive as it appears today, this simple prototype became the first production motorcycle engineered as one integrated design. True, it used what essentially amounted to Hendee’s bicycle chassis, and the engine was borrowed from Hedstrom’s motor-pacer. But the way it was put together rendered it so well conceived that for years no other cycle could match it. That first machine now rests in the Smithsonian Institution.

To review the design, the long-stroke one-lunger became part of the chassis, its cylinder top wedged tightly into the seat post, the crankcase firmly affixed to the bottom of the frame. This engine delivered 1.75 bhp from roughly 15 cu. in. Hedstrom incorporated a very advanced carburetor with a concentric float. Other mechanical features were equally ahead of their time—relatively high compression, and a weatherproof ignition system working from dry cell batteries with a make-and-break jump spark. The engine responded instantly to throttle and spark and gave amazing flexibility for its time.

This prototypal Indian (and its successors up to the Twin of 1905) used three block-link chains and no clutch. To start the engine, the rider released the compression petcock, pedaled to sufficient speed, closed the petcock, and putted off down the road. Curb weight of the early Indian was 98 lb.

All Indian motorcycles from 1901 through 1904 were essentially identical. Demand was instant and mainly far ahead of production. During 1901, only three Indians were built; in 1902, 143; in 1903, 377; in 1904, 546. This tiny trickle came nowhere near matching the public’s thirst for fast, reliable motorcycles, and as the Indian’s reputation grew, especially in regard to its reliability and its winning of competitive events, the waiting list for new Indians became ever longer.

In 1902, an Indian, driven by George Holden on the Brooklyn Cycle Path, won the nation’s first motorcycle race by covering 10 miles at a speed of just under 45 mph. At the nationally prestigious Ft. George Hillclimb in the Bronx (May 30, 1902), another Indian ran far and away ahead of all competition. In America’s first national endurance contest, a run of 250 miles from New York to Boston, Indians again showed the way—three of them finished with perfect scores and won gold medals (the only cycles to do so). Drivers on this occasion were none other than Hendee, Hedstrom, and Holden.

Indians again took all gold at the next year’s Ft. George Hillclimb (1903).

The ’03 Indian shown in the accompanying photos is not original in some respects. Fred Gomez left on the kickstand that someone had built for it somewhere along the line. Also, most early Indians have “Camel Back” gasoline tanks mounted over the rear fender just behind the Brooks saddle. When Gomez bought Chelini’s machine, its tank hung from the upper frame member. Gomez believes that this, too, must have been changed along the line, but he says that the words “INDIAN, Hendee Mfg. Co., Springfield, Mass.” were clearly visible in company-style gold lettering over the faded blue paint. It’s possible that this might have been a factoryor dealer-modified model built especially for racing. At any rate, in restoring this machine, Gomez left the unique tank in its unusual position and simply had a specialist re-letter the faded inscription.

While this writer was taking photos of Gomez’ venerable 1903 machine, a mailman happened past on his appointed rounds. He walked up to the Indian, looked it over carefully, and asked, “Is this one of them new ones?” Fred Gomez smiled and answered, “No, but it was one of them new ones 65 years ago.”