Riding The Winner

Rayborn's H-D: A critique from the clipons. . .

IVAN J. WAGAR

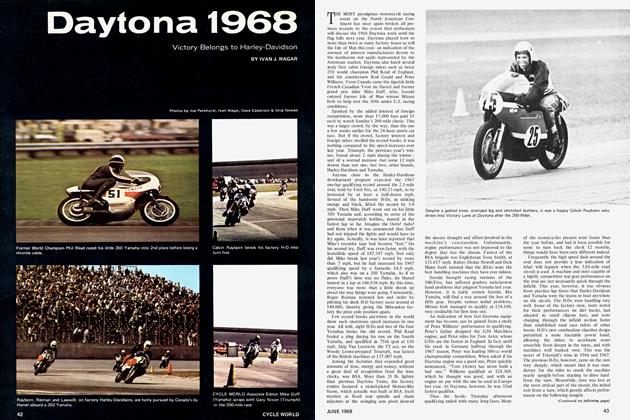

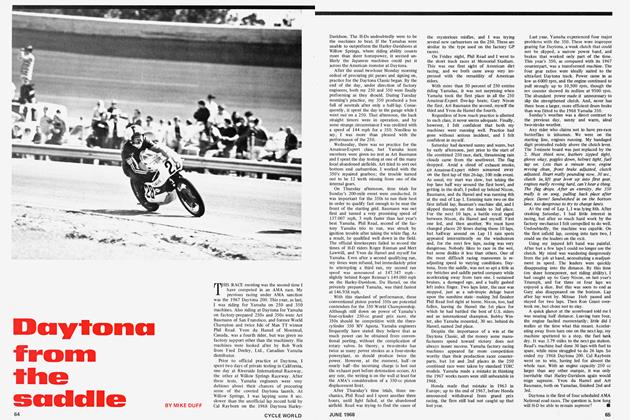

RIDING Cal Rayborn's winning Harley-Davidson is an experience not soon forgotten. The beast (any motorcycle that will go 150 mph is a beast) was taken to Riverside Raceway just as it had finished the Daytona 200-mile grind. By the time I rode the machine, it had a total of 300 practice and race miles, yet the engine was tight and mechanically very quiet. There was no indication whatever of worn lower ends or valve gear, and even from cold the engine sounded as though it would be quite happy to do another 200 miles if called upon to do so.

The whole motorcycle had been washed down, and was as clean as when it started the 200-mile race. However, I saw the machine immediately after the race at Daytona, and oil leakage was surprisingly small. The rear half of the bike was unusually dry, particularly the rear tire, which was completely oil free.

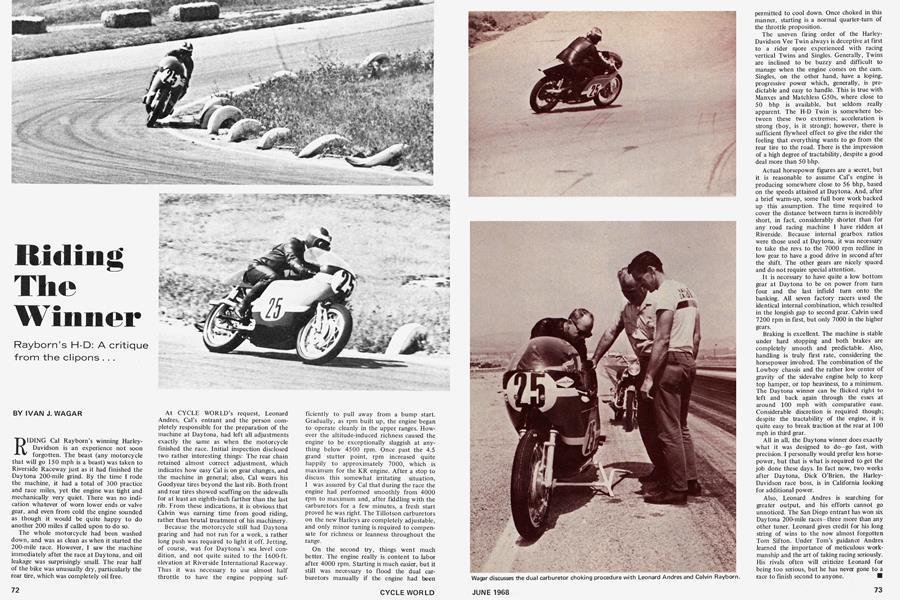

At CYCLE WORLD’S request, Leonard Andres, Cal’s entrant and the person completely responsible for the preparation of the machine at Daytona, had left all adjustments exactly the same as when the motorcycle finished the race. Initial inspection disclosed two rather interesting things: The rear chain retained almost correct adjustment, which indicates how easy Cal is on gear changes, and the machine in general; also, Cal wears his Goodyear tires beyond the last rib. Both front and rear tires showed scuffing on the sidewalls for at least an eighth-inch farther than the last rib. From these indications, it is obvious that Calvin was earning time from good riding, rather than brutal treatment of his machinery.

Because the motorcycle still had Daytona gearing and had not run for a week, a rather long push was required to light it off. Jetting, of course, was for Daytona’s sea level condition, and not quite suited to the 1600-ft. elevation at Riverside International Raceway. Thus it was necessary to use almost half throttle to have the engine popping sufficiently to pull away from a bump start. Gradually, as rpm built up, the engine began to operate cleanly in the upper ranges. However the altitude-induced richness caused the engine to be exceptionally sluggish at anything below 4500 rpm. Once past the 4.5 grand stutter point, rpm increased quite happily to approximately 7000, which is maximum for the KR engine. After a stop to discuss this somewhat irritating situation, I was assured by Cal that during the race the engine had performed smoothly from 4000 rpm to maximum and, after fiddling with the carburetors for a few minutes, a fresh start proved he was right. The Tillotson carburetors on the new Harleys are completely adjustable, and only minor tuning is required to compensate for richness or leanness throughout the range.

On the second try, things went much better. The engine really is content to labor after 4000 rpm. Starting is much easier, but it still was necessary to flood the dual carburetors manually if the engine had been permitted to cool down. Once choked in this manner, starting is a normal quarter-turn of the throttle proposition.

The uneven firing order of the HarleyDavidson Vee Twin always is deceptive at first to a rider njore experienced with racing vertical Twins and Singles. Generally, Twins are inclined to be buzzy and difficult to manage when the engine comes on the cam. Singles, on the other hand, have a loping, progressive power which, generally, is predictable and easy to handle. This is true with Manxes and Matchless G50s, where close to 50 bhp is available, but seldom really apparent. The H-D Twin is somewhere between these two extremes; acceleration is strong (boy, is it strong); however, there is sufficient flywheel effect to give the rider the feeling that everything wants to go from the rear tire to the road. There is the impression of a high degree of tractability, despite a good deal more than 50 bhp.

Actual horsepower figures are a secret, but it is reasonable to assume Cal’s engine is producing somewhere close to 56 bhp, based on the speeds attained at Daytona. And, after a brief warm-up, some full bore work backed up this assumption. The time required to cover the distance between turns is incredibly short, in fact, considerably shorter than for any road racing machine I have ridden at Riverside. Because internal gearbox ratios were those used at Daytona, it was necessary to take the revs to the 7000 rpm redline in low gear to have a good drive in second after the shift. The other gears are nicely spaced and do not require special attention.

It is necessary to have quite a low bottom gear at Daytona to be on power from turn four and the last infield turn onto the banking. All seven factory racers used the identical internal combination, which resulted in the longish gap to second gear. Calvin used 7200 rpm in first, but only 7000 in the higher gears.

Braking is excellent. The machine is stable under hard stopping and both brakes are completely smooth and predictable. Also, handling is truly first rate, considering the horsepower involved. The combination of the Lowboy chassis and the rather low center of gravity of the sidevalve engine help to keep top hamper, or top heaviness, to a minimum. The Daytona winner can be flicked right to left and back again through the esses at around 100 mph with comparative ease. Considerable discretion is required though; despite the tractability of the engine, it is quite easy to break traction at the rear at 100 mph in third gear.

All in all, the Daytona winner does exactly what it was designed to do-go fast, with precision. I personally would prefer less horsepower, but that is what is required to get the job done these days. In fact now, two weeks after Daytona, Dick O’Brien, the HarleyDavidson race boss, is in California looking for additional power.

Also, Leonard Andres is searching for greater output, and his efforts cannot go unnoticed. The San Diego entrant has won six Daytona 200-mile races-three more than any other tuner. Leonard gives credit for his long string of wins to the now almost forgotten Tom Sifton. Under Tom’s guidance Andres learned the importance of meticulous workmanship and the art of taking racing seriously. His rivals often will criticize Leonard for being too serious, but he has never gone to a race to finish second to anyone. ■