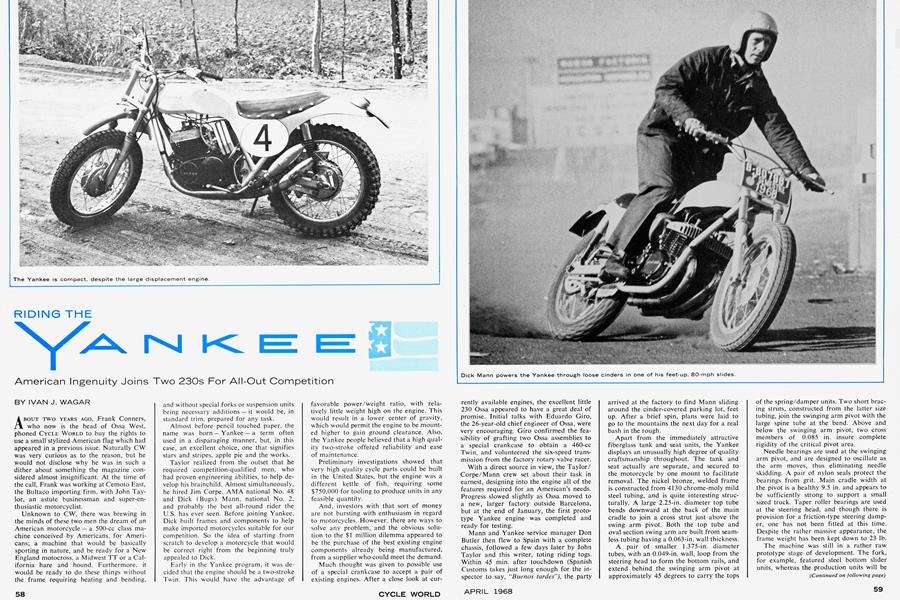

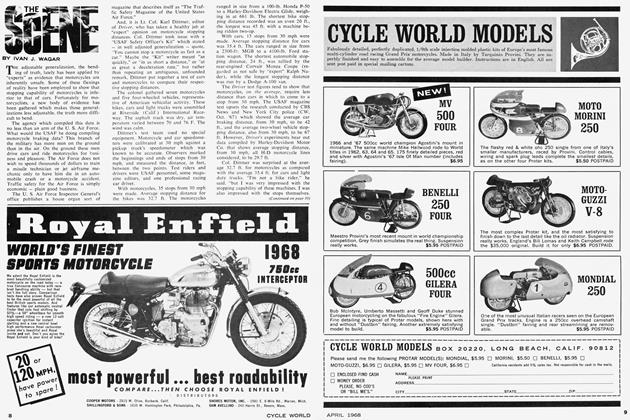

RIDING THE YANKEE

American Ingenuity Joins Two 230s For All-Out Competition

IVAN J. WAGAR

ABOUT TWO YEARS AGO, Frank Conners, who now is the head of Ossa West, phoned CYCLE WORLD to buy the rights to use a small stylized American flag which had appeared in a previous issue. Naturally CW was very curious as to the reason, but he would not disclose why he was in such a dither about something the magazine considered almost insignificant. At the time of the call, Frank was working at Cemoto East, the Bultaco importing firm, with John Taylor, an astute businessman and super-enthusiastic motorcyclist.

Unknown to CW, there was brewing in the minds of these two men the dream of an American motorcycle — a 500-cc class machine conceived by Americans, for Americans; a machine that would be basically sporting in nature, and be ready for a New England motocross, a Midwest TT or a California hare and hound. Furthermore, it would be ready to do these things without the frame requiring heating and bending, and without special forks or suspension units being necessary additions — it would be, in standard trim, prepared for any task.

Almost before pencil touched paper, the name was born — Yankee — a term often used in a disparaging manner, but, in this case, an excellent choice, one that signifies stars and stripes, apple pie and the works.

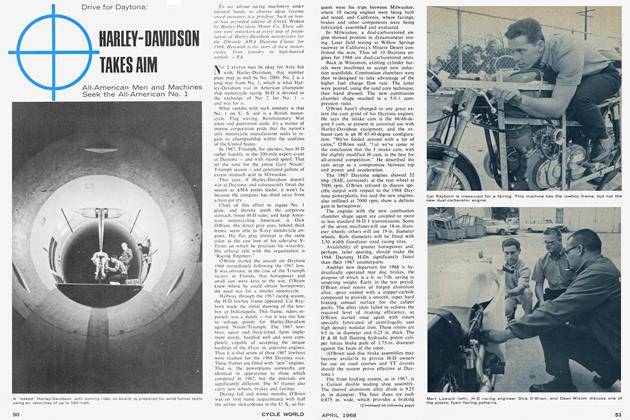

Taylor realized from the outset that he required competition-qualified men, who had proven engineering abilities, to help develop his brainchild. Almost simultaneously, he hired Jim Corpe. AMA national No. 48 and Dick (Bugs) Mann, national No. 2, and probably the best all-round rider the U.S. has ever seen. Before joining Yankee, Dick built frames and components to help make imported motorcycles suitable for our competition. So the idea of starting from scratch to develop a motorcycle that would be correct right from the beginning truly appealed to Dick.

Early in the Yankee program, it was decided that the engine should be a two-stroke Twin. This would have the advantage of favorable power/weight ratio, with relatively little weight high on the engine. This would result in a lower center of gravity, which would permit the engine to be mounted higher to gain ground clearance. Also, the Yankee people believed that a high quality two-stroke offered reliability and ease of maintenance.

Preliminary investigations showed that very high quality cycle parts could be built in the United States, but the engine was a different kettle of fish, requiring some $750,000 for tooling to produce units in any feasible quantity.

And, investors with that sort of money are not bursting with enthusiasm in regard to motorcycles. However, there are ways to solve any problem, and the obvious solution to the $1 million dilemma appeared to be the purchase of the best existing engine components already being manufactured, from a supplier who could meet the demand.

Much thought was given to possible use of a special crankcase to accept a pair of existing engines. After a close look at currently available engines, the excellent little 230 Ossa appeared to have a great deal of promise. Initial talks with Eduardo Giro, the 26-year-old chief engineer of Ossa, were very encouraging. Giro confirmed the feasibility of grafting two Ossa assemblies to a special crankcase to obtain a 460-cc Twin, and volunteered the six-speed transmission from the factory rotary valve racer.

With a direct source in view, the Taylor/ Corpe/Mann crew set about their task in earnest, designing into the engine all of the features required for an American's needs. Progress slowed slightly as Ossa moved to a new, larger factory outside Barcelona, but at the end of January, the first prototype Yankee engine was completed and ready for testing.

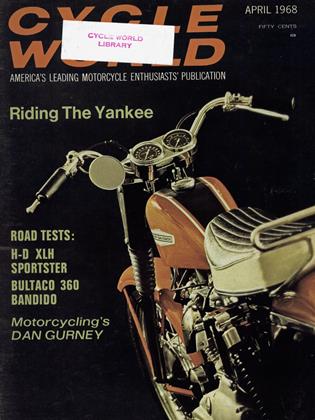

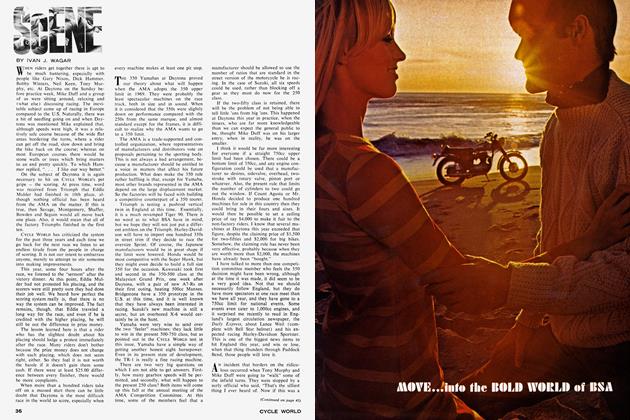

Mann and Yankee service manager Don Butler then flew to Spain with a complete chassis, followed a few days later by John Taylor and this writer, toting riding togs. Within 45 min. after touchdown (Spanish Customs takes just long enough for the inspector to say, "Buenos tardes"), the party arrived at the factory to find Mann sliding around the cinder-covered parking lot, feet up. After a brief spin, plans were laid to go to the mountains the next day for a real bash in the rough.

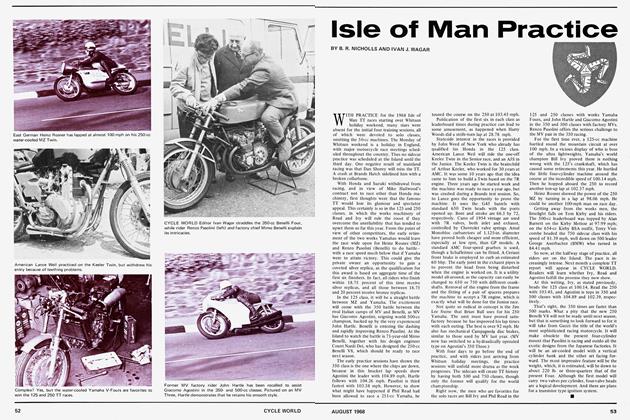

Apart from the immediately attractive fiberglass tank and seat units, the Yankee displays an unusually high degree of quality craftsmanship throughout. The tank and seat actually are separate, and secured to the motorcycle by one mount to facilitate removal. The nickel bronze, welded frame is constructed from 4130 chrome-moly mild steel tubing, and is quite interesting structurally. A large 2.25-in. diameter top tube bends downward at the back of the main cradle to join a cross strut just above the swing arm pivot. Both the top tube and oval section swing arm are built from seamless tubing having a 0.063-in. wall thickness.

A pair of smaller 1.375-in. diameter tubes, with an 0.049-in. wall, loop from the steering head to form the bottom rails, and extend behind the swinging arm pivot at approximately 45 degrees to carry the tops of the spring/damper units. Two short bracing struts, constructed from the latter size tubing, join the swinging arm pivot with the large spine tube at the bend. Above and below the swinging arm pivot, two cross members of 0.085 in. insure complete rigidity of the critical pivot area.

Needle bearings are used at the swinging arm pivot, and are designed to oscillate as the arm moves, thus eliminating needle skidding. A pair of nylon seals protect the bearings from grit. Main cradle width at the pivot is a healthy 9.5 in. and appears to be sufficiently strong to support a small sized truck. Taper roller bearings are used at the steering head, and though there is provision for a friction-type steering damper, one has not been fitted at this time. Despite the rather massive appearance, the frame weight has been kept down to 23 lb.

The machine was still in a rather raw prototype stage of development. The fork, for example, featured steel bottom slider units, whereas the production units will be constructed trom aluminum. It has been decided to use the larger diameter (41.5 mm) stanchions, as employed by the Rickman Brothers on their famous Metisse machines. At present, Yankee also uses Rickman triple clamps, but these might be swapped for fabricated sheet steel components later. The Spanish Telesco concern is busy making up damper units to Yankee specifications for the front fork.

(Continued on following page)

The test venue was the area to be used for the International Six Days Trial when Spain plays host in 1969. The terrain is very similar to Southern California, and quite unlike most parts of Europe. It is a guess that Californians will do very well in the Spanish ISDT.

The anticipation of riding a prototype — a motorcycle so new that only three people have ridden it before — is somewhat of an overwhelming experience. Engineers expect prototypes to be crude development vehicles, but this writer eagerly hoped for perfection from the beginning.

And, in most respects, perfection is exactly what was discovered in the Yankee. Sitting on the machine gives the impression of a large displacement motorcycle, but balance and "feel" is more akin to a large 250. Starting the engine is an effortless one prod proposition. The Spanish IRZ carburetors worked well on idle and responded favorably to throttle changes during warmup. There was some evidence of light vibration, probably accentuated by the very rigid frame, but Taylor does not feel it will be a problem to adjust the balance factor slightly to suit the Yankee chassis.

The Yankee's six-speed gearbox is near perfection. One of the test roads was identical to a California "fire trail" with flat out stretches on which the 90-mph maximum often could be used to the full extent. But when it was necessary to back shift, once or even twice, the clutch could be ignored completely. In fact, once underway, the clutch is not needed until it is time to make a pit stop. It is inconceivable that a rider would encounter a situation where he would be off-power.

Despite a rather ferocious top end, riding actually was done on a "woods bike," as it's known in the East. And, though the engine pulls from idle, strong power is evident at 5000 rpm. However, keeping the wheel spinning, or keeping it from spinning, simply is a matter of combining the movements of right foot and hand only.

Handling can be described as slow, and completely predictable. There was no indication that a steering damper would be required at any time. The Yankee shows no signs of wanting to shake its head, or waggle the front end, or misbehave when landing on the front wheel, or any of those truly evil things that cause a rider to work up a sweat about his future health.

During the day, Dick Mann simulated trials, TT, rough scrambles, and performed wheelies for a mile down the road. John Taylor plowed through anything that looked like New England country. And, when no one was looking, CW'S representative tried a little road racing. None found anything serious to complain about when it came time to partake in one of the best bench racing sessions ever. Next month. CYCLE WORLD will feature a complete analysis of the unique Yankee engine.