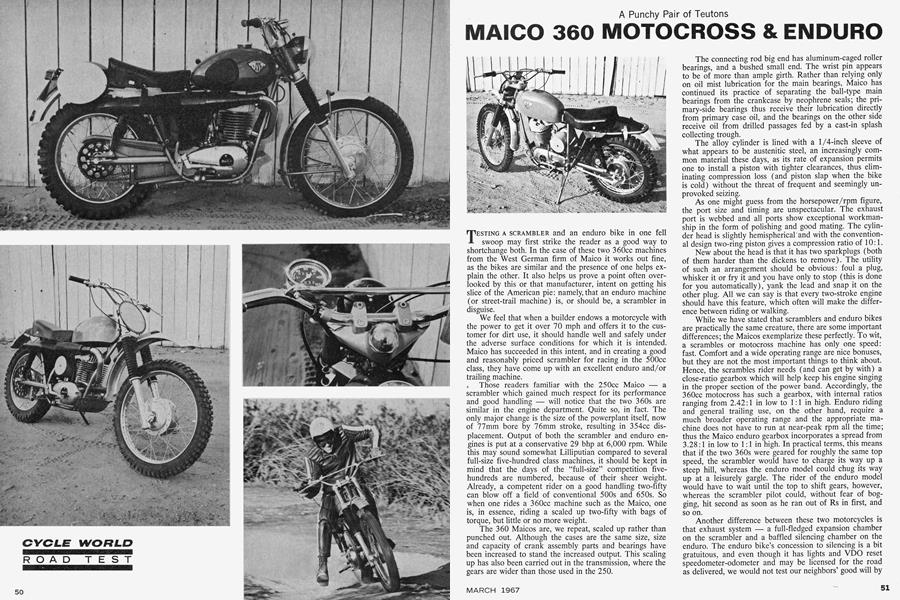

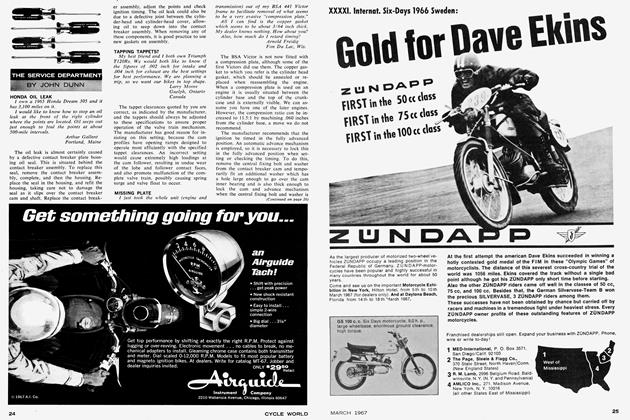

CYCLE WORLD ROAD TEST

MAICO 360 MOTOCROSS & ENDURO

A Punchy Pair of Teutons

TESTING A SCRAMBLER and an enduro bike in one fell swoop may first strike the reader as a good way to shortchange both. In the case of these two 360cc machines from the West German firm of Maico it works out fine, as the bikes are similar and the presence of one helps explain the other. It also helps us prove a point often overlooked by this or that manufacturer, intent on getting his slice of the American pie: namely, that an enduro machine (or street-trail machine) is, or should be, a scrambler in disguise.

We feel that when a builder endows a motorcycle with the power to get it over 70 mph and offers it to the customer for dirt use, it should handle well and safely under the adverse surface conditions for which it is intended. Maico has succeeded in this intent, and in creating a good and reasonably priced scrambler for racing in the 500cc class, they have come up with an excellent enduro and/or trailing machine.

. Those readers familiar with the 250cc Maico — a scrambler which gained much respect for its performance and good handling — will notice that the two 360s are similar in the engine department. Quite so, in fact. The only major change is the size of the powerplant itself, now of 77mm bore by 76mm stroke, resulting in 354cc displacement. Output of both the scrambler and enduro engines is put at a conservative 29 bhp at 6,000 rpm. While this may sound somewhat Lilliputian compared to several full-size five-hundred class machines, it should be kept in mind that the days of the “full-size” competition fivehundreds are numbered, because of their sheer weight. Already, a competent rider on a good handling two-fifty can blow off a field of conventional 500s and 650s. So when one rides a 360cc machine such as the Maico, one is, in essence, riding a scaled up two-fifty with bags of torque, but little or no more weight.

The 360 Maicos are, we repeat, scaled up rather than punched out. Although the cases are the same size, size and capacity of crank assembly parts and bearings have been increased to stand the increased output. This scaling up has also been carried out in the transmission, where the gears are wider than those used in the 250.

The connecting rod big end has aluminum-caged roller bearings, and a bushed small end. The wrist pin appears to be of more than ample girth. Rather than relying only on oil mist lubrication for the main bearings, Maico has continued its practice of separating the ball-type main bearings from the crankcase by neophrene seals; the primary-side bearings thus receive their lubrication directly from primary case oil, and the bearings on the other side receive oil from drilled passages fed by a cast-in splash collecting trough.

The alloy cylinder is lined with a 1/4-inch sleeve of what appears to be austenitic steel, an increasingly common material these days, as its rate of expansion permits one to install a piston with tighter clearances, thus eliminating compression loss (and piston slap when the bike is cold) without the threat of frequent and seemingly unprovoked seizing.

As one might guess from the horsepower/rpm figure, the port size and timing are unspectacular. The exhaust port is webbed and all ports show exceptional workmanship in the form of polishing and good mating. The cylinder head is slightly hemispherical and with the conventional design two-ring piston gives a compression ratio of 10:1.

New about the head is that it has two sparkplugs (both of them harder than the dickens to remove). The utility of such an arrangement should be obvious: foul a plug, whisker it or fry it and you have only to stop (this is done for you automatically), yank the lead and snap it on the other plug. All we can say is that every two-stroke engine should have this feature, which often will make the difference between riding or walking.

While we have stated that scramblers and enduro bikes are practically the same creature, there are some important differences; the Maicos exemplarize these perfectly. To wit, a scrambles or motocross machine has only one speed: fast. Comfort and a wide operating range are nice bonuses, but they are not the most important things to think about. Hence, the scrambles rider needs (and can get by with) a close-ratio gearbox which will help keep his engine singing in the proper section of the power band. Accordingly, the 360cc motocross has such a gearbox, with internal ratios ranging from 2.42:1 in low to 1:1 in high. Enduro riding and general trailing use, on the other hand, require a much broader operating range and the appropriate machine does not have to run at near-peak rpm all the time; thus the Maico enduro gearbox incorporates a spread from 3.28:1 in low to 1:1 in high. In practical terms, this means that if the two 360s were geared for roughly the same top speed, the scrambler would have to charge its way up a steep hill, whereas the enduro model could chug its way up at a leisurely gargle. The rider of the enduro model would have to wait until the top to shift gears, however, whereas the scrambler pilot could, without fear of bogging, hit second as soon as he ran out of Rs in first, and so on.

Another difference between these two motorcycles is that exhaust system — a full-fledged expansion chamber on the scrambler and a baffled silencing chamber on the enduro. The enduro bike’s concession to silencing is a bit gratuitous, and even though it has lights and VDO reset speedometer-odometer and may be licensed for the road as delivered, we would not test our neighbors’ good will by running it up and down the street too often. The distributor is now making arrangements to sell the enduro model with a spark arrester, which is easier on the ears, as well as keeping the forestry service happy.

With the lighting on the enduro machine comes a Bosch battery-generator system with automatic spark advance, an item which allows the pleasure of one-stab, kickfree starts. We couldn’t understand at first why the allegedly identical scrambler engine tended to “snap,” until we discovered that it is fitted with a Bendix magneto having fixed advance — a lightweight no-nonsense unit quite appropriate for an out-and-out racer, particularly as it is said to give a good spark up to about 10,000 rpm. The enduro bike has what amounts to a second ignition, should the battery system fail; by changing the positions of two wires, one switches to a magneto coil set-up and continues on in good fettle, sans battery.

The greatest design change on these new Maicos, of course, is the frame, which consists of single top tube, but a continuous double cradle, reinforced and triangulated by two tubes linking the top tube with the swing arm assembly. The new arrangement would seem to provide good overall resistance to twisting as well as a rigid guide for a healthy looking swing arm. Maico has taken the long wheelbase approach to building dirt machinery, and the distance between axle centers is now a whopping 55.5 inches, a figure nearly the equal of that for one or two 400-pound 650cc class scramblers we have ridden. The result of this, as expected, is good straight-line stability over rough surfaces and slowish, predictable handling, a plus factor for the novice as well as the expert.

The front end on the enduro model is heavier feeling than that of the scrambler. Part of this is due to the weight of the headlight unit and speedo on the enduro; also the heavier looking fender is unsprung weight on the enduro model, while a lightweight fender is mounted high on the scrambler and sprung with the frame.

Suspension on these otherwise identically hung bikes seemed as different as night and day. The scrambler had a much stiffer, more positive feel, while the enduro was an extremely comfortable, languid cross-country machine. Push the speeds up and it was the scrambler’s turn to feel comfortable, as the enduro bike transformed itself from magic carpet to rocking horse. The secret is in the type of rear spring, rather than the tension: constant rate springs with uniform winding on the scrambler and multirate springs with tightening end spirals on the enduro job. The advantage of a multi-rate spring is that it will give a very comfortable ride under easy-going conditions. The disadvantage, of course, is that one sacrifices about an inch or more effective travel when the going gets rough and fast. In addition, one is in constant transition between the soft and hard phase of spring compression — not the most desirable situation if predictability is your goal. Fortunately, the buyer of the enduro bike will have the option of single-rate springs, should he desire them.

We should not neglect to mention such touches as the skid plates, chain guides and Fram paper-element filtration on both Maicos, as well as the use of that great rebendable Magura control hardware.

The reader will also note that the Maico 360s retail for nearly the same price, even though the enduro model seems to come with a lot more equipment. This is because more attention has been paid to weight saving in the scrambler, the cost of which shows up in the choice of gasoline tank, fenders and sprockets.

Both of these are competitive machines ready to give good service as delivered. They are not as exotic as “last year’s works bike,” nor are they in the world championship class when it comes to light weight. But then, they don’t cost as much, either. Which one the reader chooses would depend mainly on his preference for closeor wide-ratio gearbox, as well as the anticipated use. The enduro would be a fun scooter for the woods or desert buff who likes to move fast. The scrambler would require someone with a harder gleam in his eye. ■

MAICO 360

MOTOCROSS & ENDURO

$998