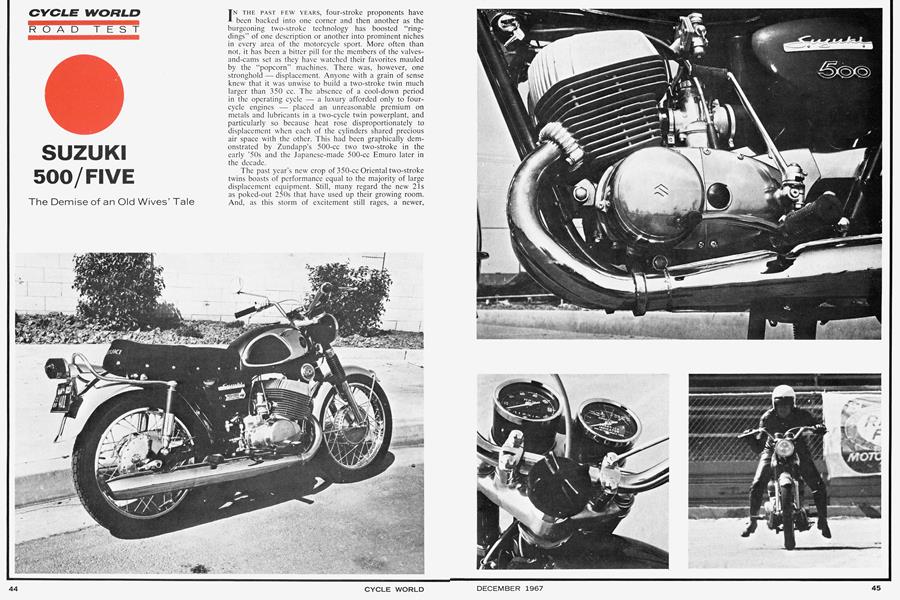

SUZUKI 500/FIVE

CYCLE WORLD ROAD TEST

The Demise of an Old Wives' Tale

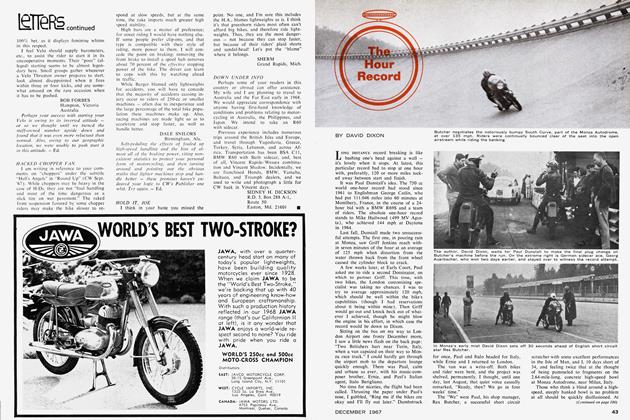

IN THE PAST FEW YEARS, four-stroke proponents have been backed into one corner and then another as the burgeoning two-stroke technology has boosted "ringdings" of one description or another into prominent niches in every area of the motorcycle sport. More often than not, it has been a bitter pill for the members of the valves-and-cams set as they have watched their favorites mauled by the "popcorn" machines. There was, however, one stronghold — displacement. Anyone with a grain of sense knew that it was unwise to build a two-stroke twin much larger than 350 cc. The absence of a cool-down period in the operating cycle — a luxury afforded only to four-cycle engines — placed an unreasonable premium on metals and lubricants in a two-cycle twin powerplant, and particularly so because heat rose disproportionately to displacement when each of the cylinders shared precious air space with the other. This had been graphically demonstrated by Zundapp's 500-cc two two-stroke in the early '50s and the Japanese-made 500-cc Emuro later in the decade.

The past year's new crop of 350-cc Oriental two-stroke twins boasts of performance equal to the majority of large displacement equipment. Still, many regard the new 21s as poked-out 250s that have used up their growing room. And, as this storm of excitement still rages, a newer, bigger, faster two-stroke bomb, the Suzuki 500./Five, is dropped on us, and we see the myth concerning displacement limitations for two-cycle engines go flitting out the window. Is nothing sacred?

The Suzuki 500/Five — or something just like it — was bound to appear at about this time; in the past ten years, industry in general has enjoyed an explosively expanding technology in metallurgy, in heat dissipation schemes, and in lubrication, and with this growth has come a greater understanding of the fundamentals of physics. Perhaps this seems a rather grand spring-board from which to launch an analysis of an everyday device such as a motorcycle — but then, the 500/Five is a rather grand motorcycle that, like as not, would not have been feasible a few years ago.

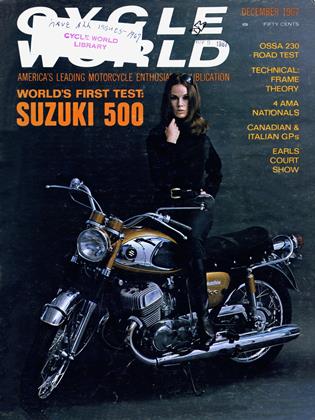

The 500/Five doesn't depart from current, common design practice. It simply has all the accepted items — in spades. Its built-up crank is carried in three massive roller bearing assemblies. These are mated to the horizontally split cases with O-ring seals which prevent oil from seeping between the bearing recesses and the outer races into the clutch and electrical chambers.

In the smaller twins, adequate clutch oiling is assured by routing oil, cast from the gearbox into a reservoir that supplies oil to the center main bearing, into the clutch chamber where it duly returns to the transmission — at least that is what is supposed to occur. Most of the time this system works well, but occasionally the clutch chamber finds inself with more oil than it needs, while the top-mounted gears in the transmission run high and dry for want of a sufficiently high oil level. The 500/Five Suzuki still employs transmission oil to lubricate the center main, but, instead of routing the oil into the clutch chamber, it is returned directly to the transmission. The clutch is supplied by way of a passage from the transmission that ensures that both systems have neither more nor less lubrication than they require.

The caged needle bearing assemblies at both ends of the connecting rods are noticeably heavy duty. Both are lubricated by oil mist which is created when the straight oil from the Posi-Force lubrication system passes through the outer main bearings and into the crank chambers where it is mixed with the incoming fuel/air mixture. The connecting rod big ends are split, to expose the middles of the needle bearing assemblies to the oil-mist atmosphere in the crank chambers.

The 500/Five's pistons bear examination because they employ windows, rather than notches, for port control. This design, uncommon in production machines because of its higher manufacturing cost, provides the pistons with full-circumference skirts that are stronger than notched ones, and quieter; the "bridges" between the solid portions of the skirt damp, to a great degree, the rattling operating sound that is common to notched-skirt pistons. The massive alloy cylinders are fitted with an equally generous set of steel liners that will comfortably accept a couple of rebores. Replacement pistons will be offered in 0.020 and 0.040 in. oversize, and when this rejuvenation approach has been exhausted, the cylinders can be refitted with new liners of the original dimension.

Porting is not as generous as might be expected of an engine that performs as strongly as this one. Abundant material around the ports promises good potential to the performance-minded enthusiast. Barrel-to-cylinder mating of the ports is quite good. The soft state of tune of the 500/Five is evidenced again by the mild geometric compression ratio of 6.6:1 for the hemi-chambered heads.

On the intake side of the track is the 500/Five's pair of great walloping 34-mm Mikuni VMs, with excellent delivery capabilities. Despite their choke sizes, the carburetors are pleasantly tractable at all engine speeds. On this point, much credit must be given to the method used to vent the float chambers. A static probe-like port is cast into the intake nozzle and is connected to the float chamber with a cast-in passage. Air passing through the intake siphons air from the port and, consequently, from the float chamber. At low engine speeds, with proportionately low intake velocities, the siphon effect is moderate and, as a result, a desirable pressure is maintained in the ullage portion of the sealed float chamber to prevent more fuel than is required from entering the chamber. Conversely, as engine speed increases, and with it intake velocity, the siphon effect increases and lowers the ullage pressure in the float chamber, which permits the fuel flow rate into the chamber to increase to meet the engine's increased requirements. Paired with the vacuum-operated positiveshutoff fuel tank tap, introduced on the X-5, the 500/ Five's carburetors offer one of the most advanced fuel feed systems to be found in motorcycling.

The totality of the 500/Five development program appeared time and again throughout evaluation and road testing. The transmission, for example, departs significantly — but not drastically — from what could be expected from Suzuki's competent gear train designers, who already have some good things going for them with the X-5 and X-6 layouts. The key innovation is the drum shifter assembly which, instead of using encircling shifting forks on the drum, employs stubby half forks, mounted on an independent shaft, that have nubs which engage the indexing slots on the drum. This design results in a reduction of fork-to-drum contact area that is attended by an absence of galling which occurs when minute particles from wearing-in gears happen to slip between a shifter drum and an encircling fork.

Chief characteristic of the transmission is sturdiness, with wide gears, needle bearings inboard on the shafts, and rollers supporting the ends. The transmission receives an additional and unfamiliar chore on this model; a worm gear on the "lazy" end of the countershaft drives the oil pump. Potentially, the only thing wrong with this is that neither the pump, nor the tachometer, operates when the clutch is disengaged. Realistically, this is of no consequence unless, of course, the engine were run at high speed with the clutch pulled in for a long period of time.

The Suzuki family resemblance is strong in the new chassis. Its appearance is a scale-up of its two smaller brothers. The frame is constructed of heavy-wall tubing, fabricated gussets, fine welding, and satisfying triangulation. In general, the frame is a full duplex design that departs from the "accepted standard" in that the base tubes do not arc upward to meet the top tubes at the seat/tank juncture, but, instead, incline casually up and rearward to intersect the top members at the upper rear shock mount. The rear swing arm assembly is stout, reinforced by a large gusset aft of the pivot tube.

The 500/Five can be faulted on only one point, suspension. Unfortunately, for a motorcycle as fast as this one, poor suspension is a grievous shortcoming. The entire suspension system is not to be harshly criticized, however. The rear spring-shock units are well applied to their duties with spring rates that suit the weight and purpose of the motorcycle and damping that cannot be disparaged. The front fork assembly is another matter. It is plagued with a set of too-soft springs and cursed with dampers that would scarcely be missed if they were left at home. Conversation with service reps from U.S. Suzuki revealed that experiments with damping oil many weight grades heavier than recommended had improved the condition, but certainly not cured it. It's entirely possible, however, that this problem soon will be rectified by a design change.

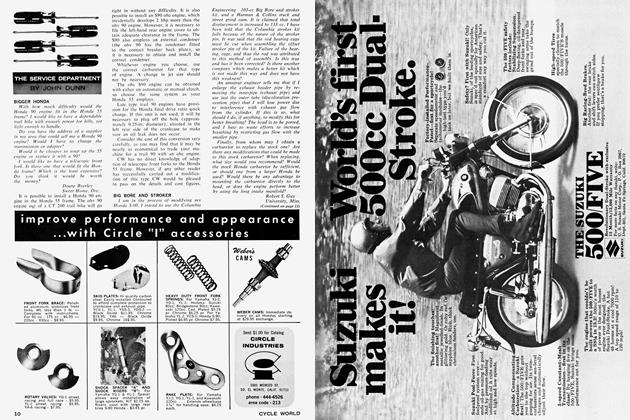

During performance testing the 500/Five's strength was clearly demonstrated when CW alternated acceleration runs with U.S. Suzuki's flyweight road tester. His all-or-nothing technique produced a slightly better ET — 13.9 — but a lower speed — 91.4 mph.

Some of the 500/Five's more endearing virtues — performance aside — concern its civility and suitability as a high-speed tourer. There's little question that a great deal of money and head scratching have gone into the design of the exhaust system which is pleasantly throaty and totally inoffensive.

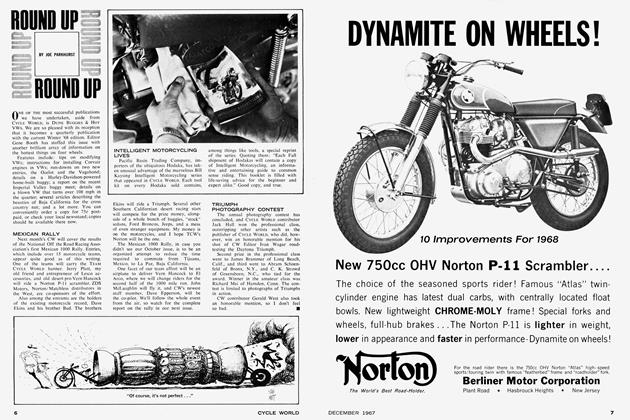

Riding position and comfort are very agreeable, and the bike readily accommodates riders sized from medium to extra large. The seat, covered in a non-slip material, is a little too firm and tends to become board-like after several hours of riding without a break. Controls positioning and action, with exception of the gear selector, are so satisfactory that the motorcycle has an instant athome feeling. Selector movement is longer than it should be, and missed cogs — particularly the 4th to 5th change — are a regular thing if the left foot is not moved decisively upward. However, this is something that can be lived with, and it's not difficult to call to mind a dozen other motorcycles that are more irritating in this respect.

The 500/Five's brakes are superb with predictable action and high fade resistance. The front unit, as might be expected, is a robust, double-leading-shoe unit that can be encouraged to completely stop the front wheel at almost any speed. Used prudently, it is a comfortable confidence builder that offers a wide margin of safety.

Suzuki has been a leader in providing customers with proper electrical systems. (Suzuki was one of the first two manufacturers to win acceptance of lighting systems by the very particular California Highway Patrol.) The components on the 500/Five indicate Suzuki remains a leader in this area. Lights are very bright at any engine speed, all switches perform without flaw, and circuit integrity is perfect. The AC ignition is partially independent of the main electrical system in that the engine can be started and run with a dead battery, or with no battery at all. However, this is recommended only as an emergency measure because the ignition is dependent upon battery current to augment its output at low engine speed.

Viewed as a package, a concept, a milestone, the Suzuki 500/Five qualifies as one of the most exciting and best engineered motorcycles on today's market. It has exploded an absurd myth and may, itself, be destined to become a legend, or, at the very least, a benchmark at the beginning of a brand new game. ■

SUZUKI 500/FIVE

$1039