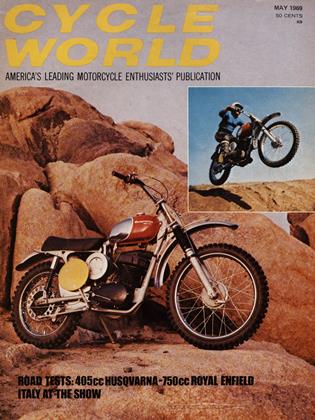

ROYAL ENFIELD STAGE II INTERCEPTOR

CYCLE WORLD ROAD TEST

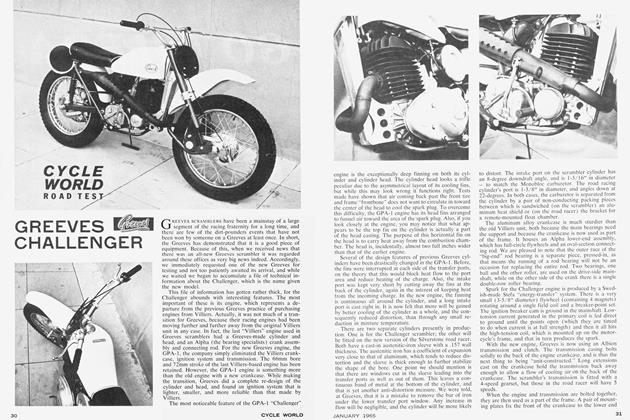

Fabulous Handling And Braking Mark This Heavyweight For The Enthusiast

SOME PEOPLE THINK caverns are reserved solely for truffles, troglodytes, and an occasional spelunker; not so. Royal Enfields are made in caves underneath England. Inside a vast complex of tunnels and caverns hewn from the earth during World War II, where the temperature stays at a constant 58 degrees year-round, men are hard at work assembling motorcycles for the Surface People. With ritual befitting a Druid sacrifice, white-cloaked mechanics assemble the enormously powerful Interceptors.

Big machine, the Enfield. Strong and authoritative, like Little John of Sherwood Forest. Sure, machines are just metal pieces with a plan, but there is a magical something about this bike that throbs with the sap of life and a chivalrous serenity. Its sturdy mien will always stand out amid a shock of motorcycles because enthusiasm for the machine is just a natural reaction. It cannot be taken for granted; after riding it, one feels impelled to take notes of his experience and save them for retelling and retelling.

The Enfield epitomizes the British road burner, and many riders speak of it with reverence. It is a machine for the rabid road enthusiast. Not everyone rides one: the machine demands a special sort of rider, one who can appreciate its rock-steady handling, its solidness, and that unique husky exhaust note that says “Big Guns.” The Enfield is up to the bigness of America, but this doesn’t mean that its rider will be a devotee of long-distance touring or rally riding. It is more likely you’ll find him out alone—perhaps on the same stretch of twisting valley and mountain road that he’s covered a hundred weekends in a row—only each weekend he does it a little better, a little harder, and he concentrates even more... Man alone, pitted against pavement, rock walls, flying trees, dizzy mountains, careening white lines, and he’s really into it to the very depth of his existence. The Enfield’s long-gaited jog compliments the experience and makes it feel motionless. Apply full throttle and the machine growls soulfully, carrying its rider into the future.

The 736-cc engine is big. It is tall because of the long stroke, 3.66 in., though the bore measures a relatively narrow 2.8 in. A lot of metal is needed to maintain any kind of discipline with 60 bhp at 6500 rpm, so the crankcase and transmission case are gargantuan castings. The crankshaft is an integral assembly cast in nodular iron. It is supported by two huge (3.34-in.) main bearings, ball bearings on the primary side and a roller bearing on the timing side.

Lubrication is by a dry sump system with an auto-type oil filter. The latter is not just a gauze strainer but a felt filter element. This is a valuable contribution to long engine life but its benefits are offset somewhat by the lack of carburetor air cleaners. The most irritating vice the Enfield showed was its propensity to leak oil, particularly from the gearbox cover and the primary chain cover. This situation is not entirely foreign to English machines, nor is it typical of them; it’s just there.

The Stage II Interceptor engine is substantially different from its predecessors. With previous models, oil was carried in a cavity between the transmission and the crankcase. The Stage II has an entirely new crankcase. There is now a finned, integral oil tank below the engine. This arrangement allows for both a quick oil warmup when the engine is cold and direct oil cooling as air flows past the finned sump. In spite of this new design, ground clearance is a spacious 5.75 in.

The stout and smooth transmission shifted positively every time. Finding neutral involved no terpsichorean exercise which is usually the case with most new bikes. Nevertheless, the exclusive Royal Enfield neutral finder is there, next to one’s right heel; it makes an easy chore easier. The ratios are well-spaced, though the Interceptor has enough power to make ratios seem incidental. Clutch operation is light. Minimal slippage is required to get the motorcycle underway. The semi-wet, multi-disc unit showed no sign of yielding to the engine’s brutish (44.2 ft./lb.) torque when not authorized. Even with all that carburetion and sporty cam timing the Enfield chuffs away from the stoplight in second gear with little clutch feathering.

The Interceptor’s frame isolates the rider well from engine vibration. The large diameter front downtube is bolted to the front of the engine and the rear downtubes are bolted to the rear of the transmission. The loop is completed by the transmission being bolted to the engine. In this way, the engine-transmission unit serves as a frame member. The bike can be ridden deep into a curve, leaned over to the pegs and powered through without a hint of flexion anywhere. The chrome-moly steel frame weighs only 26 lb. and deserves much credit for the bike’s fine handling.

The Interceptor is surprisingly nimble and handles like a much lighter machine. Ostensibly, it appears too big for maneuvering of any sort. On the contrary, the motorcycle has regal manners and is capable of the most elaborate prancmgs and gambades. The only criticism we can make regarding its handling is that the footpegs are too low. In turns, the bike can be leaned over farther than footpeg location allows. The Stage II Interceptor's wheelbase has been extended from 57 to 58 in. This has smoothed out the Enfield's ride in all circumstances. It shows no tendency to shudder or wobble in turns. The longer wheelbase seems to have made the machine more sensitive to rider control.

The Interceptor's front brake has been enlarged in diameter from 7 to 8 in., while the width is unchanged at 1.5 in. The rear brake retains its original dimensions of 7 by 1.25 in. These units do an admirable job of hauling down the 435-lb. (curb weight) Interceptor from the awesome speeds of which it is capable. The action of both brakes is light and positive. Cold starting is easy. The 8.5:1 compression ratio offered little resistance to the swing of the right-side kickstarter. Two or three kicks will start the fire after the 30-mm Ama! concentrics are tickled and fully choked and the throttle is opened about a quarter turn. Warm starting takes more of a knack and less throttle. Too much can result in a stern warning applied to the sole of one's right foot as the engine rejects the mixture.

The Enfield showed a definite reluctance to idle. Slow running was not always its forte, either. The engine would surge uncomfortably at small to moderate throttle openings. This irascibility did not make things easy in city traffic. Floyd Clymer, Royal Enfield distributor for states west of the Mississippi River, indicated that because the CW test model was one of the first off the production line, it was equipped with un-modified Ama! 930 concentric carburetors. Forthcom ing Enfields will use redesigned concentrics, for smoother operation. For those who have the earlier carburetors, a remedial kit is available from Barnes Enterprises in Inglewood, Calif.

ignition chores are dispatched by a dual breaker point, a battery-coil system with automatic advance. Also incorporated into the system is a Zener diode. This unit acts as a voltage regulator by converting excess electricity into heat which is dissipated by a heat-sink. The diode is located directly in front of the right spring/dampener. The ignition system never failed to deliver a good spark. The ammeter, mounted on the headlight nacelle, always gave good account of the Lucas capacitor system's activities. .

The finish of the Royal Enfield Stage II Interceptor is lavish, but good. The all chrome gas tank (2.7-gal. capacity) with a wide red center stripe, black frame, and polished alloy fork heads dazzle the eye in a most pleasing way. The bike attracts lots of attention and when riding the Interceptor one is imbued with a feeling of omnipotence. Soon its rider learns that most people fare poorly at hiding envy.

Undoubtedly, many will expect that the Royal-Enfield, being of such large displacement, would deliver its rider some fantastic speed and acceleration figures. Not so. The machine tested by CYCLE WORLD was singularly unastonishing. it will top 100 mph, which is fast enough for most people, and it will turn a quarter-mile in the middle 80s, which is passable. Interestingly, the Royal-Enfield 750 Interceptor tested by CYCLE WORLD four years ago was a much faster machine. One may draw two conclusions: either Enfields are getting slower, or the CYCLE WORLD test machine was in deplorable mechanical state. The latter idea is somewhat frightening, for if such a poorly prepared machine is given to CYCLE WORLD, think what the poor guy who walks in off the street must get. Either conclusion is rather sad.

ROYAL ENFIELD STAGE II INTERCEPTOR

$1495

SPECIFICATIONS

PERFORMANCE

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Round Up

Round UpRound Up

May 1969 By Joe Parkhurst -

The Service Department

The Service DepartmentThe Service Department

May 1969 By John Dunn -

Letters

LettersLetters

May 1969 -

The Scene

The SceneThe Scene

May 1969 By Ivan J. Wagar -

Travel

TravelSpecial Report: the Moving Forces Behind Motorcycle Legislation

May 1969 By J. Bradley Flippin -

Travel

TravelCycle To Solitude

May 1969 By James Tallon