BSA CYCLONE 500

CYCLE WORLD ROAD TEST

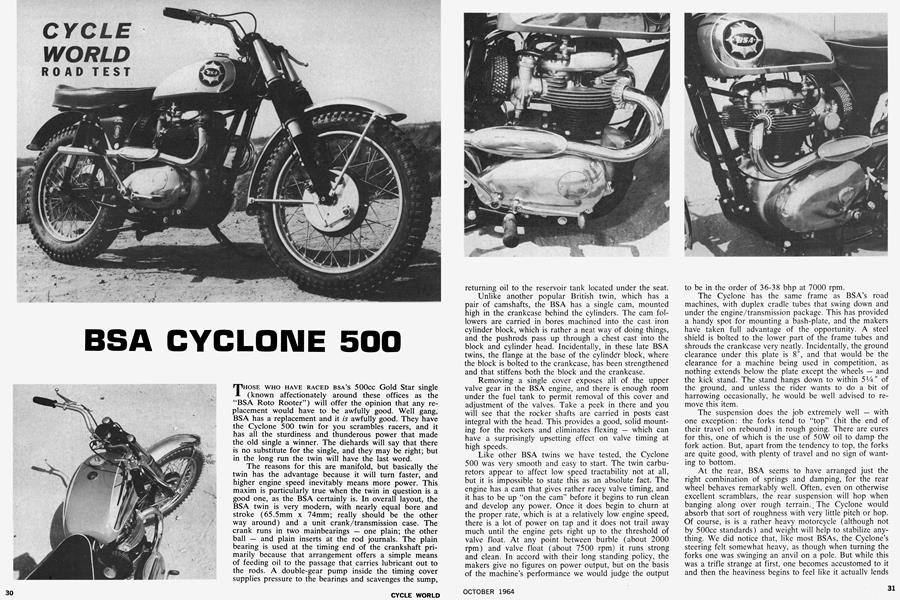

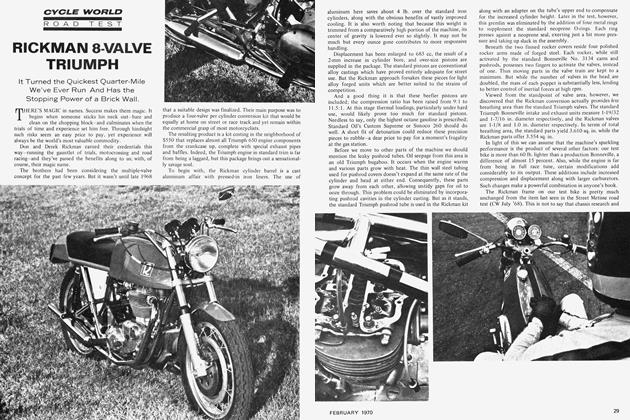

THOSE WHO HAVE RACED BSA'S 500CC Gold Star single (known affectionately around these offices as the "BSA Roto Rooter") will offer the opinion that any replacement would have to be awfully good. Well gang, BSA has a replacement and it is awfully good. They have the Cyclone 500 twin for you scrambles racers, and it has all the sturdiness and thunderous power that made the old single a winner. The diehards will say that there is no substitute for the single, and they may be right; but in the long run the twin will have the last word.

The reasons for this are manifold, but basically the twin has the advantage because it will turn faster, and higher engine speed inevitably means more power. This maxim is particularly true when the twin in question is a good one, as the BSA certainly is. In overall layout, the BSA twin is very modern, with nearly equal bore and stroke (65.5mm x 74mm; really should be the other way around) and a unit crank/transmission case. The crank runs in two mainbearings — one plain; the other ball — and plain inserts at the rod journals. The plain bearing is used at the timing end of the crankshaft primarily because that arrangement offers a simple means of feeding oil to the passage that carries lubricant out to the rods. A double-gear pump inside the timing cover supplies pressure to the bearings and scavenges the sump, returning oil to the reservoir tank located under the seat.

Unlike another popular British twin, which has a pair of camshafts, the BSA has a single cam, mounted high in the crankcase behind the cylinders. The cam followers are carried in bores machined into the cast iron cylinder block, which is rather a neat way of doing things, and the pushrods pass up through a chest cast into the block and cylinder head. Incidentally, in these late BSA twins, the flange at the base of the cylinder block, where the block is bolted to the crankcase, has been strengthened and that stiffens both the block and the crankcase.

Removing a single cover exposes all of the upper valve gear in the BSA engine, and there is enough room under the fuel tank to permit removal of this cover and adjustment of the valves. Take a peek in there and you will see that the rocker shafts are carried in posts cast integral with the head. This provides a good, solid mounting for the rockers and eliminates flexing — which can have a surprisingly upsetting effect on valve timing at high speeds.

Like other BSA twins we have tested, the Cyclone 500 was very smooth and easy to start. The twin carburetors appear to affect low speed tractability not at all, but it is impossible to state this as an absolute fact. The engine has a cam that gives rather racey valve timing, and it has to be up "on the cam" before it begins to run clean and develop any power. Once it does begin to churn at the proper rate, which is at a relatively low engine speed, there is a lot of power on tap and it does not trail away much until the engine gets right up to the threshold of valve float. At any point between burble (about 2000 rpm) and valve float (about 7500 rpm) it runs strong and clean. In accord with their long standing policy, the makers give no figures on power output, but on the basis of the machine's performance we would judge the output to be in the order of 36-38 bhp at 7000 rpm.

The Cyclone has the same frame as BSA's road machines, with duplex cradle tubes that swing down and under the engine/transmission package. This has provided a handy spot for mounting a bash-plate, and the makers have taken full advantage of the opportunity. A steel shield is bolted to the lower part of the frame tubes and shrouds the crankcase very neatly. Incidentally, the ground clearance under this plate is 8", and that would be the clearance for a machine being used in competition, as nothing extends below the plate except the wheels — and the kick stand. The stand hangs down to within 5 VA " of the ground, and unless the rider wants to do a bit of harrowing occasionally, he would be well advised to remove this item.

The suspension does the job extremely well — with one exception: the forks tend to "top" (hit the end of their travel on rebound) in rough going. There are cures for this, one of which is the use of 50W oil to damp the fork action. But, apart from the tendency to top, the forks are quite good, with plenty of travel and no sign of wanting to bottom.

At the rear, BSA seems to have arranged just the right combination of springs and damping, for the rear wheel behaves remarkably well. Often, even on otherwise excellent scramblers, the rear suspension will hop when banging along over rough terrain.. The Cyclone would absorb that sort of roughness with very little pitch or hop. Of course, is is a rather heavy motorcycle (although not by 500cc standards) and weight will help to stabilize anything. We did notice that, like most BSAs, the Cyclone's steering felt somewhat heavy, as though when turning the forks one was swinging an anvil on a pole. But while this was a trifle strange at first, one becomes accustomed to it and then the heaviness begins to feel like it actually lends stability to the bike. In any case, for whatever reasons, the steering is not unduly affected when the front tire clips large humps, rocks etc., and the motorcycle will go where it is aimed with commendable precision.

The handlebars are the proper length, and nicely positioned, and fitted with ball-end levers and comfortable squishy rubber grips. Even the most bony of hindsides will find the wide, soft seat very comfortable, and the distance from seat to pegs and seat to ground will suit riders in the average size range. The tank is rather wide, but as the engine width more or less limits the amount the bike can be narrowed, a smaller tank wouldn't make too much difference.

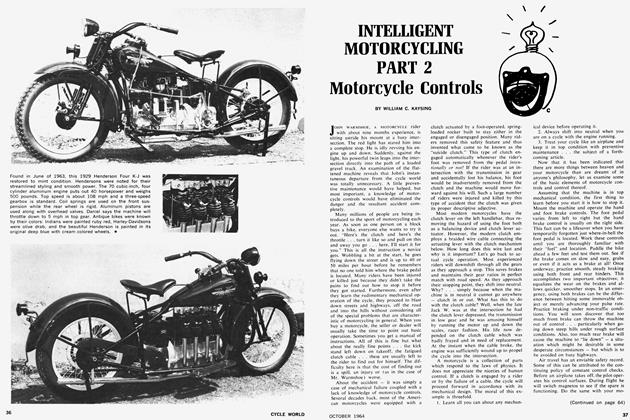

Genuine evidence of the popularity of this machine and the other models in the new BSA unit twin series is the fact that they are virtually impossible to find, the demand is so intense. We were forced to obtain the use of our test machine from a BSA dealer, rather than from the distributor in the West, Hap Alzina, in Oakland. Norm Reeves, BSA/Honda dealer in Paramount, California, let us make a used machine of one of these rare birds, and Jim Hunter, leading 500cc scrambles Expert in Southern California prepared it for us. Hunter rides under Reeves' sponsorship on a BSA single but will soon make the single to twin transition himself.

Now for the things we didn't particularly like. We think it would be wise to provide a tachometer on the Cyclone, as the engine will rev more willingly than is really good for the various moving pieces, and knowing how fast it is turning would help in selecting gearing for different courses. We appreciated the very neatly mounted heat shields on the high exhaust pipes, but we would have liked the arrangement better if the kick-start pedal had not insisted on swinging around and jamming into the shield when released. When this happens, it props the kick lever back far enough to hold the starter drive in engagement, and you get a fine, ghastly grinding noise from the ratchet mechanism. There is no real danger to the equipment, as long as you hear it and reach down and flip the pedal away from the shield so that the lever can come forward, but it is an annoyance and should be corrected. Finally, we were less than enchanted with the position of the kill button. Good luck to you riders in trying to chop the engine after a high speed burst for a spark plug reading; perhaps you can punch the button with your nose.

We can also register a big gripe about the gearing, which is now tall enough for road racing at the Isle of Man; but the gearing is being changed. With the gearing we had on our test machine, it was all but impossible to get the engine speed up enough to keep it on the cam in slow going, and it hampered our runs at the drag strip. It is a tribute to the good low-speed torque of the engine that the Cyclone performed as well as it did.

The brakes on our test bike squealed something shocking, but we rather suspect that this was due to their not being bedded in completely. And, even with the squealing, they did the job of stopping the motorcycle quite well.

The word is that the change in gearing will be done by changing the present 21-tooth countershaft sprocket for one having 16-teeth. This will give an overall ratio of 6.62:1, and that will do a lot more for the machine than the existing 4.93:1 gearing.

Although handicapped by poorly chosen gearing in its present form, the BSA Cyclone 500 Scrambler is still a most vigorous performer, and the gearing can be changed easily enough. Moreover, the BSA impressed us as being put together with more than average care, and the flogging we gave our test bike had no perceptible effect oh its willingness to start after a couple of moderately hard kicks. Nor, did the flogging make the engine smoke, or develop any of those tell-tale ticks in the valve gear nor indeed to show any signs of distress whatever. In all, we consider the Cyclone to be an entirely worthy successor to the venerable and venerated Gold Star single.

BSA CYCLONE 500

SPECIFICATIONS

POWER TRANSMISSION

PERFORMANCE