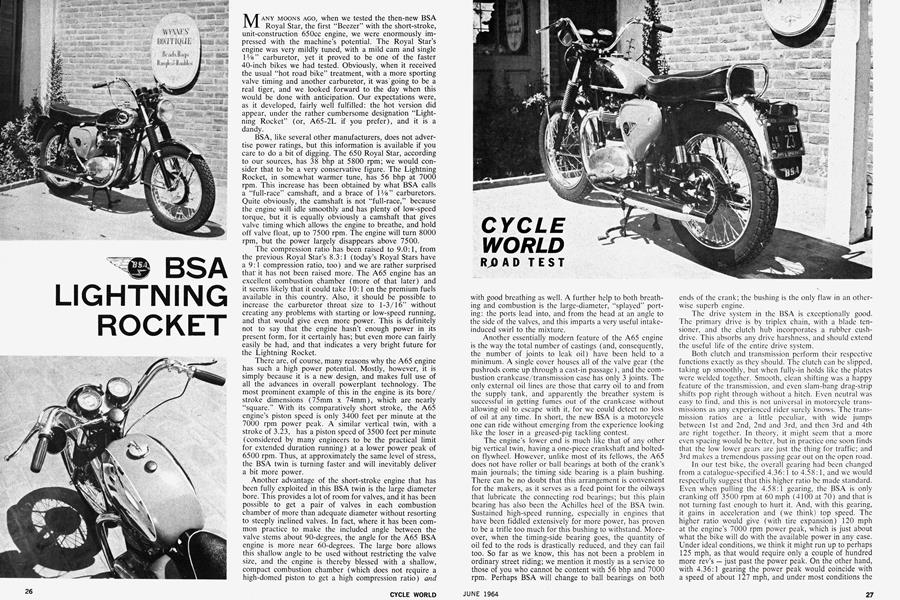

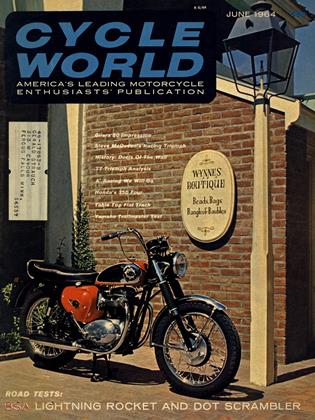

BSA LIGHTNING ROCKET

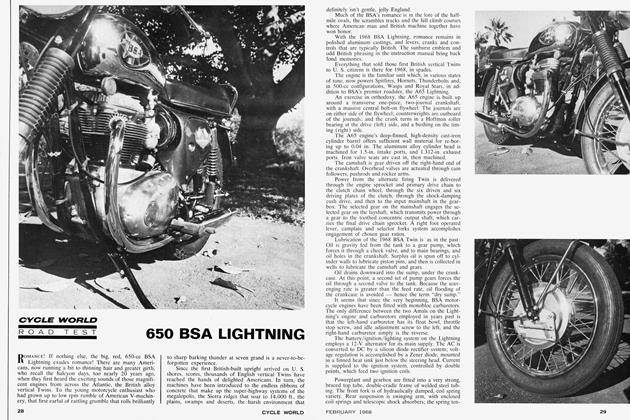

MANY MOONS AGO, when we tested the then-new BSA Royal Star, the first "Beezer" with the short-stroke, unit-construction 650cc engine, we were enormously impressed with the machine's potential. The Royal Star's engine was very mildly tuned, with a mild cam and single 1⅛" carburetor, yet it proved to be one of the faster 40-inch bikes we had tested. Obviously, when it received the usual "hot road bike" treatment, with a more sporting valve timing and another carburetor, it was going to be a real tiger, and we looked forward to the day when this would be done with anticipation. Our expectations were, as it developed, fairly well fulfilled: the hot version did appear, under the rather cumbersome designation "Lightning Rocket" (or, A65-2L if you prefer), and it is a dandy.

BSA, like several other manufacturers, does not advertise power ratings, but this information is available if you care to do a bit of digging. The 650 Royal Star, according to our sources, has 38 bhp at 5800 rpm; we would consider that to be a very conservative figure. The Lightning Rocket, in somewhat warmer tune, has 56 bhp at 7000 rpm. This increase has been obtained by what BSA calls a "full-race" camshaft, and a brace of 1 Va " carburetors. Quite obviously, the camshaft is not "full-race," because the engine will idle smoothly and has plenty of low-speed torque, but it is equally obviously a camshaft that gives valve timing which allows the engine to breathe, and hold off valve float, up to 7500 rpm. The engine will turn 8000 rpm, but the power largely disappears above 7500.

The compression ratio has been raised to 9.0:1, from the previous Royal Star's 8.3:1 (today's Royal Stars have a 9:1 compression ratio, too) and we are rather surprised that" it has not been raised more. The A65 engine has an excellent combustion chamber (more of that later) and it seems likely that it could take 10:1 on the premium fuels available in this country. Also, it should be possible to increase the carburetor throat size to 1-3/16" without creating any problems with starting or low-speed running, and that would give even more power. This is definitely not to say that the engine hasn't enough power in its present form, for it certainly has; but even more can fairly easily be had, and that indicates a very bright future for the Lightning Rocket.

There are, of course, many reasons why the A65 engine has such a high power potential. Mostly, however, it is simply because it is a new design, and makes full use of all the advances in overall powerplant technology. The most prominent example of this in the engine is its bore/ stroke dimensions (75mm x 74mm), which are nearly "square." With its comparatively short stroke, the A65 engine's piston speed is only 3400 feet per minute at the 7000 rpm power peak. A similar vertical twin, with a stroke of 3.23, has a piston speed of 3500 feet per minute (considered by many engineers to be the practical limit for extended duration running) at a lower power peak of 6500 rpm. Thus, at approximately the same level of stress, the BSA twin is turning faster and will inevitably deliver a bit more power.

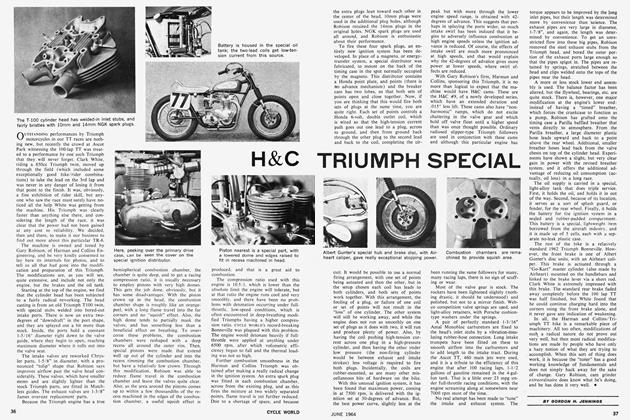

Another advantage of the short-stroke engine that has been fully exploited in this BSA twin is the large diameter bore. This provides a lot of room for valves, and it has been possible to get a pair of valves in each combustion chamber of more than adequate diameter without resorting to steeply inclined valves. In fact, where it has been common practice to make the included angle between the valve stems about 90-degrees, the angle for the A65 BSA engine is more near 60-degrees. The large bore allows this shallow angle to be used without restricting the valve size, and the engine is thereby blessed with a shallow, compact combustion chamber (which does not require a high-domed piston to get a high compression ratio) and with good breathing as well. A further help to both breathing and combustion is the large-diameter, "splayed'1 porting: the ports lead into, and from the head at an angle to the side of the valves, and this imparts a very useful intakeinduced swirl to the mixture.

CYCLE WORLD ROAD TEST

Another essentially modern feature of the A65 engine is the way the total number of castings (and, consequently, the number of joints to leak oil) have been held to a minimum. A single cover houses all of the valve gear (the pushrods come up through a cast-in passage), and the combustion crankcase/transmission case has only 3 joints. The only external oil lines are those that carry oil to and from the supply tank, and apparently the breather system is successful in getting fumes out of the crankcase without allowing oil to escape with it, for we could detect no loss of oil at any time. In short, the new BSA is a motorcycle one can ride without emerging from the experience looking like the loser in a greased-pig tackling contest.

The engine's lower end is much like that of any other big vertical twin, having a one-piece crankshaft and boltedon flywheel. However, unlike most of its fellows, the A65 does not have roller or ball bearings at both of the crank's main journals; the timing side bearing is a plain bushing. There can be no doubt that this arrangement is convenient for the makers, as it serves as a feed point for the oilways that lubricate the connecting rod bearings; but this plain bearing has also been the Achilles heel of the BSA twin. Sustained high-speed running, especially in engines that have been fiddled extensively for more power, has proven to be a trifle too much for this bushing to withstand. Moreover, when the timing-side bearing goes, the quantity of oil fed to the rods is drastically reduced, and they can fail too. So far as we know, this has not been a problem in ordinary street riding; we mention it mostly as a service to those of you who cannot be content with 56 bhp and 7000 rpm. Perhaps BSA will change to ball bearings on both ends of the crank; the bushing is the only flaw in an otherwise superb engine.

The drive system in the BSA is exceptionally good. The primary drive is by triplex chain, with a blade tensioner, and the clutch hub incorporates a rubber cushdrive. This absorbs any drive harshness, and should extend the useful life of the entire drive system.

Both clutch and transmission perform their respective functions exactly as they should. The clutch can be slipped, taking up smoothly, but when fully-in holds like the plates were welded together. Smooth, clean shifting was a happy feature of the transmission, and even slam-bang drag-strip shifts pop right through without a hitch. Even neutral was easy to find, and this is not universal in motorcycle transmissions as any experienced rider surely knows. The transmission ratios are a little peculiar, with wide jumps between 1st and 2nd, 2nd and 3rd, and then 3rd and 4th are right together. In theory, it might seem that a more even spacing would be better, but in practice one soon finds that the low lower gears are just the thing for traffic; and 3rd makes a tremendous passing gear out on the open road.

In our test bike, the overall gearing had been changed from a catalogue-specified 4.36:1 to 4.58:1, and we would respectfully suggest that this higher ratio be made standard. Even when pulling the 4.58:1 gearing, the BSA is only cranking off 3500 rpm at 60 mph (4100 at 70) and that is not turning fast enough to hurt it. And, with this gearing, it gains in acceleration and (we think) top speed. The higher ratio would give (with tire expansion) 120 mph at the engine's 7000 rpm power peak, which is just about what the bike will do with the available power in any case. Under ideal conditions, we think it might run up to perhaps 125 mph, as that would require only a couple of hundred more rev's — just past the power peak. On the other hand, with 4.36:1 gearing the power peak would coincide with a speed of about 127 mph, and under most conditions the bike would not haul itself up to that speed. Thus, under the normal conditions of slight winds and small upgrades, the 4.58:1 gearing gives better acceleration and top speed. Clearly, the bike is faster at the end of a half-mile run, which is about as much room as anyone can usually find (and which we use to determine practical top speed).

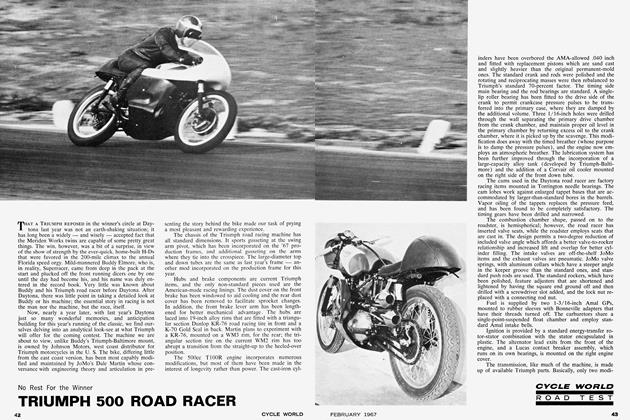

In all respects, the BSA Lightning Rocket is a rider's delight. It has a wide, soft seat, and comfortable bars, with controls positioned so that there is nothing awkward in their operation. Handling is good, though not exceptional, but the ride — which is of more immediate interest to most riders than fantastic cornering ability — was as good as anything we have experienced,. The brakes, although perfectly ordinary in specification (they even have iron drums) gave outstanding results. When running at the drag strip, we found that we could get slowed quickly enough to take an earlier return-road turnoff than is usually possible with bikes of the BSA's speed. A lot of machines have brakes that feel fine at 60-70 mph, but begin to shudder and behave badly as the machine nears the 100mph mark; we are pleased to report that the BSA's brakes are not like that.

One item we especially liked was the instrumentation. The BSA has a speedo and tach of a new type, which have eddy-current, rather than chronometric metering units, and give particularly steady readings. This sort of thing has been used before, of course, but seldom in conjunction with such large, legible dials. And, incidentally, the speedo has a built-in odometer and a quick-reset trip meter.

The Lightning Rocket's performance is quite impressive, as can be seen in the figures given on our data page, but the figures do not tell the complete story. We used 7500 rpm as a rev limit in obtaining the figures — and we could have virtually duplicated them using a thousand fewer. The BSA has a very wide range of power, and you can get startling acceleration simply by turning on the tap at any engine speed. It is not necessary to row the bike along with the shift lever. And, of course, the test results were obtained with our 190-pound "heavyweight" rider in the saddle. A lighter staff member was able to bang off a 90 mph, 14.3-second standing-quarter, and followed this with a 92 mph run after megaphones had been substituted for the standard mufflers. The elapsed time for all the quartermile runs could have been better but for the fact that the BSA was a little flat under 3000 rpm (very strong from there up) and it had such good traction that it could not be smoked away with the rear tire spinning. Slipping the clutch helped, but a real "Banzai!" run was just not possible. We tried one, and only succeeded in getting our test rider involved in a big drama with the BSA leaping along like a horse with a burr under its saddle.

Of course, the most important thing about the big BSA is that it is an extremely satisfactory machine for the sort of all-around riding for which it is intended. You can depend on it to start with a minimum of prodding; it will slog along through traffic without complaint; and it is capable of quite fast, strain-free cruising. You won't find anything that offers more day-in, day-out enjoyment, or more trouble-free service. It is not a road racer, or a scrambler, but it ranks very high on our list of sports/ touring bikes we would like to own.

BSA

LIGHTNING ROCKET

List Price $1,198, FOB L A