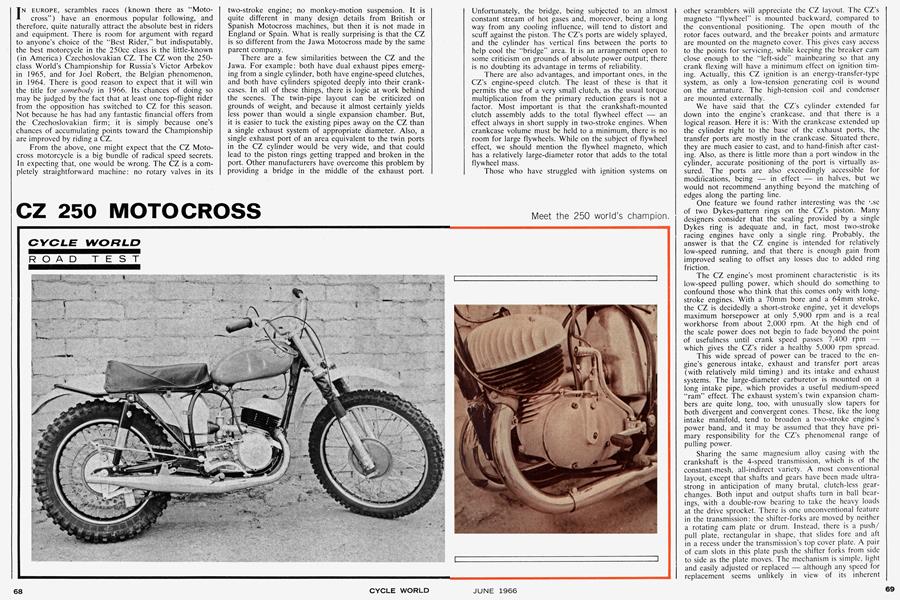

CZ 250 MOTOCROSS

CYCLE WORLD ROAD TEST

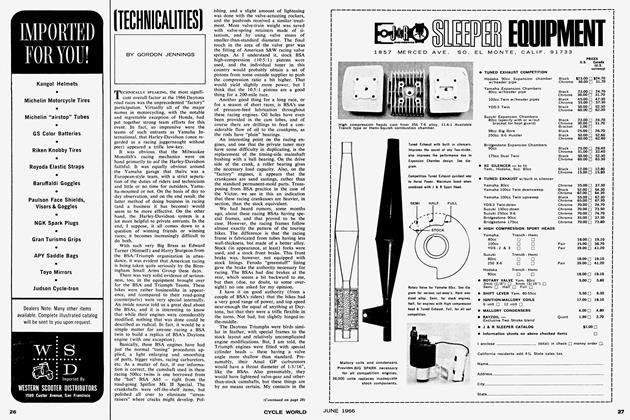

IN EUROPE, scrambles races (known there as “Motocross”) have an enormous popular following, and therefore, quite naturally attract the absolute best in riders and equipment. There is room for argument with regard to anyone’s choice of the “Best Rider,” but indisputably, the best motorcycle in the 250cc class is the little-known (in America) Czechoslovakian CZ. The CZ won the 250-class World’s Championship for Russia’s Victor Arbekov in 1965, and for Joel Robert, the Belgian phenomenon, in 1964. There is good reason to expect that it will win the title for somebody in 1966. Its chances of doing so may be judged by the fact that at least one top-flight rider from the opposition has switched to CZ for this season. Not because he has had any fantastic financial offers from the Czechoslovakian firm; it is simply because one’s chances of accumulating points toward the Championship are improved by riding a CZ.

From the above, one might expect that the CZ Motocross motorcycle is a big bundle of radical speed secrets. In expecting that, one would be wrong. The CZ is a completely straightforward machine: no rotary valves in its two-stroke engine; no monkey-motion suspension. It is quite different in many design details from British or Spanish Motocross machines, but then it is not made in England or Spain. What is really surprising is that the CZ is so different from the Jawa Motocross made by the same parent company.

There are a few similarities between the CZ and the Jawa. For example: both have dual exhaust pipes emerging from a single cylinder, both have engine-speed clutches, and both have cylinders spigoted deeply into their crankcases. In all of these things, there is logic at work behind the scenes. The twin-pipe layout can be criticized on grounds of weight, and because it almost certainly yields less power than would a single expansion chamber. But, it is easier to tuck the existing pipes away on the CZ than a single exhaust system of appropriate diameter. Also, a single exhaust port of an area equivalent to the twin ports in the CZ cylinder would be very wide, and that could lead to the piston rings getting trapped and broken in the port. Other manufacturers have overcome this problem by providing a bridge in the middle of the exhaust port. Unfortunately, the bridge, being subjected to an almost constant stream of hot gases and, moreover, being a long way from any cooling influence, will tend to distort and scuff against the piston. The CZ’s ports are widely splayed, and the cylinder has vertical fins between the ports to help cool the “bridge” area. It is an arrangement open to some criticism on grounds of absolute power output; there is no doubting its advantage in terms of reliability.

There are also advantages, and important ones, in the CZ’s engine-speed clutch. The least of these is that it permits the use of a very small clutch, as the usual torque multiplication from the primary reduction gears is not a factor. Most important is that the crankshaft-mounted clutch assembly adds to the total flywheel effect — an effect always in short supply in two-stroke engines. When crankcase volume must be held to a minimum, there is no room for large flywheels. While on the subject of flywheel effect, we should mention the flywheel magneto, which has a relatively large-diameter rotor that adds to the total flywheel mass.

Those who have struggled with ignition systems on other scramblers will appreciate the CZ layout. The CZ’s magneto “flywheel” is mounted backward, compared to the conventional positioning. The open mouth of the rotor faces outward, and the breaker points and armature are mounted on the magneto cover. This gives easy access to the points for servicing, while keeping the breaker cam close enough to the “left-side” mainbearing so that any crank flexing will have a minimum effect on ignition timing. Actually, this CZ ignition is an energy-transfer-type system, as only a low-tension generating coil is wound on the armature. The high-tension coil and condenser are mounted externally.

We have said that the CZ's cylinder extended far down into the engine’s crankcase, and that there is a logical reason. Here it is: With the crankcase extended up the cylinder right to the base of the exhaust ports, the transfer ports are mostly in the crankcase. Situated there, they are much easier to cast, and to hand-finish after casting. Also, as there is little more than a port window in the cylinder, accurate positioning of the port is virtually assured. The ports are also exceedingly accessible for modifications, being — in effect — in halves, but we would not recommend anything beyond the matching of edges along the parting line.

One feature we found rather interesting was the ».se of two Dykes-pattern rings on the CZ’s piston. Many designers consider that the sealing provided by a single Dykes ring is adequate and, in fact, most two-stroke racing engines have only a single ring. Probably, the answer is that the CZ engine is intended for relatively low-speed running, and that there is enough gain from improved sealing to offset any losses due to added ring friction.

The CZ engine’s most prominent characteristic is its low-speed pulling power, which should do something to confound those who think that this comes only with longstroke engines. With a 70mm bore and a 64mm stroke, the CZ is decidedly a short-stroke engine, yet it develops maximum horsepower at only 5,900 rpm and is a real workhorse from about 2,000 rpm. At the high end of the scale power does not begin to fade beyond the point of usefulness until crank speed passes 7,400 rpm — which gives the CZ’s rider a healthy 5,000 rpm spread.

This wide spread of power can be traced to the engine’s generous intake, exhaust and transfer port areas (with relatively mild timing) and its intake and exhaust systems. The large-diameter carburetor is mounted on a long intake pipe, which provides a useful medium-speed “ram” effect. The exhaust system’s twin expansion chambers are quite long, too, with unusually slow tapers for both divergent and convergent cones. These, like the long intake manifold, tend to broaden a two-stroke engine’s power band, and it may be assumed that they have primary responsibility for the CZ’s phenomenal range of pulling power.

Sharing the same magnesium alloy casing with the crankshaft is the 4-speed transmission, which is of the constant-mesh, all-indirect variety. A most conventional layout, except that shafts and gears have been made ultrastrong in anticipation of many brutal, clutch-less gearchanges. Both input and output shafts turn in ball bearings, with a double-row bearing to take the heavy loads at the drive sprocket. There is one unconventional feature in the transmission: the shifter-forks are moved by neither a rotating cam plate or drum. Instead, there is a push/ pull plate, rectangular in shape, that slides fore and aft in a recess under the transmission’s top cover plate. A pair of cam slots in this plate push the shifter forks from side to side as the plate moves. The mechanism is simple, light and easily adjusted or replaced — although any speed for replacement seems unlikely in view of its inherent reliability.

The CZ’s frame is uninspired, as frame designs go, but it is sturdily constructed of chrome-moly’ tubing and unquestionably strong enough for the most arduous service. The suspension is conventional, but is well damped and does its job in a manner beyond reproach. The oildamped front forks provide a total travel of 6.7", and there is over 31/2" of travel for the rear wheel. We note in the CZ Motocross owners’ manual that the forks are to be filled with 170cc of “thin engine oil” and that this is supposed to be enough to remain cool in long races and thus insure even damping characteristics. Also noted was a squib that says there is “progressive damping downward and efficient damping upward,” whatever that means.

Considerable care on the part of the makers in minimizing unsprung weight, is reflected in the use of magnesium alloy in the CZ’s hubs and brake assemblies, as well as for the engine/ transmission casing. The front brake has a pressed-in iron liner; the steel rearbrake liner is riveted in place and has an integral flange that is the rear drive sprocket. This arrangement gives you 62 teeth at the rear wheel, and the only means of changing this would be to install the 53-tooth rear hub from the 360cc model, or to add a large “overlay” sprocket. As the bike is delivered, and normally operated, overall gearing changes are made by selecting from the countershaft sprockets supplied (14, 15 and 16-tooth). The sprockets delivered with the motorcycle would cover the requirements of any European Motocross or civilized Eastern Scrambles; Western desert riders might find the 53-tooth rear hub useful for highspeed, cross-country events.

Like so many racing motorcycles, the CZ’s very impressive internal finish is balanced by a rather scruffy exterior. Castings are rough, and no effort has been made to smooth them; the various steel surfaces have been painted, but only with such care as is needed for a complete, rust-resistant coating. On the other hand, the seat is comfortable, and the positioning of foot-pegs and controls is “right.” Functional to the end, the CZ’s makers have followed the “pretty is, as pretty does” precept in almost every particular.

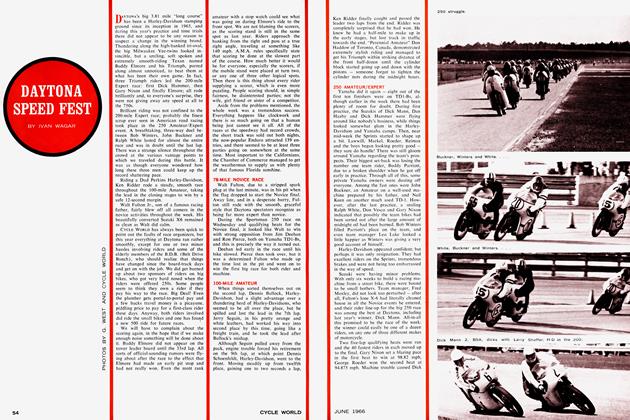

In riding the CZ Motocross, we were given a glimpse into the wonderful world of European-style scrambles. The CZ is made for that sort of thing, and it mirrors that in the way it handles, and in its engine’s power characteristics. The 2.75-21 front tire, for example, is just the thing for running in moist, tacky loam, but tends to skate away badly on hard, sandy surfaces. The engine, which is a terrific work-horse in its speed range, lacks the sheer peak horsepower for other than European-style scrambles. Here, we might also mention that the engine is virtually dead under 2,000 rpm and much over 7,000 rpm. However, it jumps to what feels like the full rated 26 bhp at 2,109 rpm and holds it all the way to 7,000 rpm. The transmission has quite closely-staged ratios, close enough for a peaky engine, but you won’t have to do much stirring of the gears to get along at a cracking pace.

The final pleasing touch, for us, was that the CZ was even fairly easy to start. A bit fussy about flooding, like many 2-strokes, but not too vexing most of the time. And if you foul a plug in slow running, just pull the spark lead from the central plug and pop it on the one at the side of the cylinderhead. The second plug is supposed to be of a slightly warmer heat range, and is there to use in case one fouls the primary plug. Running on the second plug will, of course, usually clear the first. This, like all the CZ’s many detail features, left us vastly impressed with the motorcycle.

As yet, the CZ Motocross is still a rather rare bird, and we are in the debt of arch-enthusiast Brian Fabre for loaning us his personal motorcycle for our tests. Three cheers from our staff to Mr. Fabre, and a rousing Huzzah! for the CZ 250 Motocross.

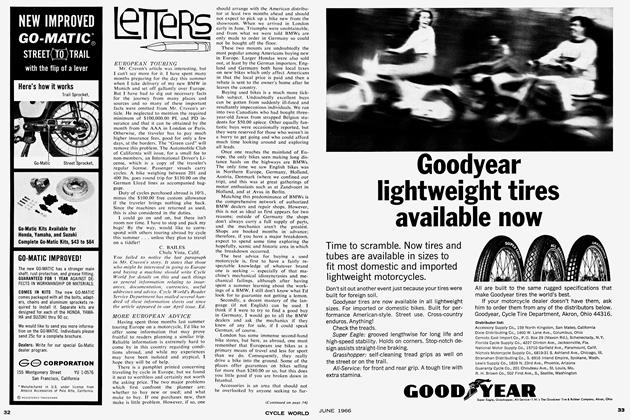

CZ 250

MOTOCROSS

SPECIFICATIONS

$895

PERFORMANCE