INTELLIGENT MOTORCYCLING

PART 2 Motorcycle Controls

WILLIAM C. KAYSING

JOHN WARMSHOE, A MOTORCYCLE rider with about nine months experience, is sitting astride his mount at a busy intersection. The red light has stared him into a complete stop. He is idly revving his engine up and down. Suddenly, against the light, his powerful twin leaps into the intersection directly into the path of a loaded gravel truck. An examination of the flattened machine reveals that John's instantaneous departure from the cycle world was totally unnecessary. A little preventive maintenance would have helped, but most important, a knowledge of motorcycle controls would have eliminated the danger and the resultant accident completely.

Many millions of people are being introduced to the sport of motorcycling each year. As soon as one person on a block buys a bike, everyone else wants to try it out. "Here's the clutch and here's the throttle . . . turn it like so and pull on this and away you go . . . here, I'll start it for you." This is all the instruction a novice gets. Wobbling a bit at the start, he goes flying down the street and is up to 40 or 50 miles per hour before he remembers that no one told him where the brake pedal is located. Many riders have been injured or killed just because they didn't take the pains to find out how to stop it before they got started. Furthermore, even after they learn the rudimentary mechanical operation of the cycle, they proceed to blast down streets and highways, off the road and into the hills without considering all of the special problems that are characteristic of motorcycling in general. When you buy a motorcycle, the seller or dealer will usually take the time to point out basic operation. Sometimes you get a manual of instructions. All of this is fine but what about the really fine points . . . the kick stand left down on takeoff, the fatigued clutch cable . . . these are usually left to the rider to find out for himself. The difficulty here is that the cost of finding out is a spill, an injury or (as in the case of Mr. Warmshoe) worse.

About the accident - it was simply a case of mechanical failure coupled with a lack of knowledge of motorcycle controls. Several decades back, most of the American motorcycles were equipped with a

clutch actuated by a foot-operated, springloaded rocker built to stay either in the engaged or disengaged position. Many riders removed this safety feature and thus invented what came to be known as the "suicide clutch." This type of clutch engaged automatically whenever the rider's foot was removed from the pedal intentionally or not! If the rider was at an intersection with the transmission in gear and accidentally lost his balance, his foot would be inadvertently removed from the clutch and the machine would move forward against his will. Such a large number of riders were injured and killed by this type of accident that the clutch was given its proper descriptive adjective.

Most modern motorcycles have the clutch lever on the left handlebar, thus removing the hazard of using the foot both as a balancing device and clutch lever actuator. However, the modern clutch employs a braided wire cable connecting the actuating lever with the clutch mechanism below. How long does this wire last and why is it important? Let's go back to actual cycle operation. Most experienced riders will downshift through all the gears as they approach a stop. This saves brakes and maintains their gear ratios in perfect match with road speed. As they approach their stopping point, they shift into neutral. Why? . . . simply because when the machine is in neutral it cannot go anywhere — clutch in or out. What has this to do with the clutch cable? Well, when the late Jack W. was at the intersection he had the clutch lever depressed, the transmission in low gear and he was amusing himself by running the motor up and down the scales, racer fashion. His life now depended on the clutch cable which was badly frayed and in need of replacement. At the instant when the cable broke, the engine was sufficiently wound up to propel the cycle into the intersection.

A motorcycle is a collection of parts which respond to the laws of physics. It does not appreciate the niceties of human control. If a clutch is engaged by a rider or by the failure of a cable, the cycle will proceed forward in accordance with its mechanical design. The moral of this example is threefold.

1. Learn all you can about any mechanical device before operating it.

2. Always shift into neutral when you are on a cycle with the engine running.

3. Treat your cycle like an airplane and keep it in top condition with preventive maintenance . . . the subject of a forthcoming article.

Now that it has been indicated that there are more things between heaven and your motorcycle than are dreamt of in anyone's philosophy, let us examine some of the basic elements of motorcycle controls and control thereof.

Assuming that the machine is in top mechanical condition, the first thing to learn before you start it is how to stop it. Mount the machine and operate the hand and foot brake controls. The foot pedal varies from left to right but the hand brake control is usually on the right side. This fact can be a lifesaver when you have temporarily forgotten just where-in-hell the foot pedal is located. Work these controls until you are thoroughly familiar with their "feel" and location. Paddle the bike ahead a few feet and test them out. See if the brake comes on slow and easy, grabs or even if it acts as a brake at all! Once underway, practice smooth, steady braking using both front and rear binders. This accomplishes two important objectives; it equalizes the wear on the brakes and allows quicker, smoother stops. In an emergency, using both brakes can be the difference between hitting some immovable object or merely advancing your pulse rate. Practice braking under non-traffic conditions. You will soon discover that too much front brake can throw the machine out of control . . . particularly when going down steep hills under rough surface conditions. Also, too much rear brake will cause the machine to "lie down" — a situation which might be desirable in some desperate circumstances — but which is to be avoided on busy highways.

Air travel has an enviable safety record. Some of this can be attributed to the continuing policy of constant control checks. Before an airplane takes off. the pilot operates his control surfaces. During flight he will switch magnetos to see if the spare is functioning. Do the same with your mo(Continued on page 64) torcycle. Before leaving, try out the brakes and occasionally while running, touch light ly to see if all necessary parts are still with you. This is particularly important after you have worked on your machine. The author can vouch for the fact that there is no feeling of helplessness quite like that obtained by depressing the brake pedal and having it go all the way down to the street. All you have to do to dupli cate this feeling is leave off the wing nut that secures the brake rod to the actuating arm following a reinstallation of the rear wheel. It's that simDle.

There is an old rule about braking that holds true for both two and four wheel drivers. If you have had to apply the brakes hard more than once in the past year, you are driving too fast for safety; repent your ways now. This is especially true for bike riders since they are their own radiator ornaments and will bear the brunt of any fast frontal contact. To summarize - an experienced rider seldom uses his brakes at all. He merely downshifts and allows engine compression to slow the cycle. He tries to avoid situations where hard braking is necessary.

The motorcycles of the future, like many of the present, will probably come equipped with electric starters. However, since a great majority of cycles still have starter levers, a word about their proper use and control. First of all, kick the lever through once or twice with ignition and gas off to check compression. Some of the larger bikes (and a few of the smaller) have enough compression to launch the novice over the bars or at least respond with a swift and painful kick in the shin. This usually occurs when the piston doesn't quite make it over top dead center and the engine fires backwards, thus kicking the starter lever violently back in the direction from whence it came. Some of the larger machines have a compression release which can take the hurt out of starting. About twenty-four years of motorcycle starting have indicated to the author that there is really no general rule to apply to problems of cycle engine starting; each machine seems to have a temperament and personality of it own. In time, its owner becomes familiar with his machine's little likes and dislikes in gas and spark setting and learns to start it with comparative ease. Although thousands of cyclists who have kicked their bikes millions of times without results will disagree (and they are welcome) it is reasonable to assume that a bike engine will start if it has the right combination of spark, gas, compression and timing.

When two people are pushing a cycle to get it started neither one of them is paying much attention to traffic. Towing is even worse and should be shunned by anyone seeking to live long enough to teach his grandchildren how to ride. In the first place, the person doing the towing (whether by cycle or car) cannot devote full attention to both front and rear activities. Thus he is likely to neglect one or the other with the usual disaster waiting in the wings. The man on the cycle being towed is in an even worse predicament. He is trying to do too many things at once. He is trying to ride a motorcycle which is being propelled in an unnatural manner . . . usually by a rope tied around the steering damper knob or on one side of the handlebars. In addition, he is busy choking, clutching, shifting, throttling and praying the ugly beast will spit some fire. It is easy to go out of control under these circumstances — the rider may spill and be dragged by the fallen bike. Also, if the engine starts suddenly, the rider may not be able to shut off in time. Find out what is wrong with your motorcycle engine and fix it. Then start it with the starter lever or button that the manufacturer provided.

Check out the cycle throttle carefully before you take a bike for a spin. Does it have a long or short travel? This is important since it determines just how fast the machine will accelerate. Many modern cycles have more horsepower than the average rider can use. "Fishtailing" or "breaking loose" can cause the novice rider to lose control. More common but also a hazard is the tendency of the novice to grab a handful of throttle, roar away from an intersection only to have to stand on the brake to stop before piling into the glut of cars waiting at the next stoplight. This misuse of the throttle is hard on the bike, the public image of motorcycling and, eventually, the rider's health and welfare.

When you have started the engine, rev it up and down a few times to get the feel of the power available. Then apply just enough power to get the machine underway and up to speed through the gears. The throttle on a motorcycle is a fairly trouble-free control but does have one tendency which bears mention . . . sticking in the open position. This attribute, along with bad brakes and snapping clutch cables has probably accounted for a good many of the "loss of control" type accidents. It can be caused by a number of different troubles but the major ones are kinked or frayed throttle cable wires and dirt between the slide and the carburetor. Again, (Continued on page 66) preventive maintenance will cure these ills before they happen but always be prepared to have the throttle stick at any position. Gear your mind to this event and it will not catch you unprepared. If and when the throttle sticks, pull in the clutch lever and begin braking. The motor (relieved of its load) will begin to scream so reach up and hit the kill button or ignition switch. When you have the machine safely stopped, make a thorough examination of all parts of the throttle linkage. If necessary, hitch a ride back to town and get new parts.

Motorcycle clutches are highly variable. Some engage at the end of lever release and others at the beginning. A good plan is to start the motor and gently release the clutch against low gear to find the engagement point. Next determine whether it is a "gentleman's" or a racing-type clutch. The former is smooth, easily depressed and engages slowly, the racing clutch is designed to come on all at once and has stiff springs. A fast acting clutch of this type coupled with a 40 or 50 horsepower engine can loop a cycle or even leave the rider behind as it takes off. The experienced rider releases the clutch lever smoothly and steadily while applying power with the throttle. The result is a smooth takeoff appealing to both the mechanical health of the motorcycle and to the viewing public. If you like the fast takeoff, • get an AMA card and take up dragging or flat track. Both are sure to satisfy anyone's urge for riding the rear wheel.

The gear shift is a foot pedal on almost all modern motorcycles. However, it varies in position and mode of operation. For example, most English makes have the pedal on the right side and follow an "up for low and down for second, third and fourth" pattern. The Triumph and 1964 BSA models have a right hand lever but reverse the pattern to down for low and the balance of the gears are changed by toeing upwards. Most German machines use this pattern but with the lever on the left side. The Japanese have followed this lead although they have one new design which allows a change in the up and down pattern. Why are gear lever differences important? .An example will illustrate this point. You are driving a new machine after years on one with the gear lever on the opposite side. You are tearing down a long hill and a herd of mountain goats comes out from behind a granite outcropping. What do you do? You automatically stomp down on what used to be the brake on your other machine only now it's the gear shift lever and presto . . . you are in a higher gear sailing through the goats.

Ask any racer who rides one type of machine on the street and another on the track and he will probably tell you that there are times when he must stop and think on which side the gear lever is located and which shift pattern it has. If you are a street rider, it is extremely important that your responses to all emergencies be automatic. There is virtually no time to think about which foot you are going to use when someone stops their Greyhound in front of you. You had best leave all your thinking to your conditioned reflexes. That is why it is best to stay with one shift pattern . . . especially if you ride both the street and the track. Don't forget to leave the transmission in neutral until you are ready to travel on.

While not strictly a control, the side stand used to support a bike at rest needs some controlling. The bicycle type which consists of a "U" shaped piece of metal is not much of a problem since it will just bounce around on the street if it gets away from its holder. The side stand, however, can be a killer. Another for instance — the author, while taking off on a mountain road one sunny afternoon, neglected to put up the. side stand on his 21-inch Velocette. While banking into the first left turn, the stand touched pavement and before kicking up automatically, which they are supposed to do, it lifted the bike off the street and caused an instantaneousloss of control. The bike recovered itself with no help from the appalled operator but a good lesson had been learned. Make it your habit to check to see if the stand is up and also assure yourself that the spring or other holding device is in good condition.

Often neglected in the roster of cycle controls is the steering damper control located directly over the steering head assembly on most machines. Turning it clockwise will increase the resistance of the forks and wheel to turn in either direction. The purpose of this stiffening action is to allow the cycle to track straighter and with less effort by the rider when traversing a rough surface. It may be left free or nearly free when the machine is used on smooth surfaces. Use this control with great care. If the steering assembly is too tight, it can cause poor control on any. surface. Work up to its use gradually and set it to suit your own particular requirements.

Adjustable shock absorbers can be approached in the same manner ... by trying the various settings to determine which will give both the best ride and easiest control on varying surfaces. Shocks which are too stiff will give a jolting ride and cause you to feel that you are riding an up-ended bed frame. Shocks which are set too mushy will cause the bike to continue to bounce up and down after passing over a bump. This could be the cause of speed wobbles or other loss of control. Experiment with shock settings on different road surfaces until you get the feeling that the machine is holding to the road as well as it can.

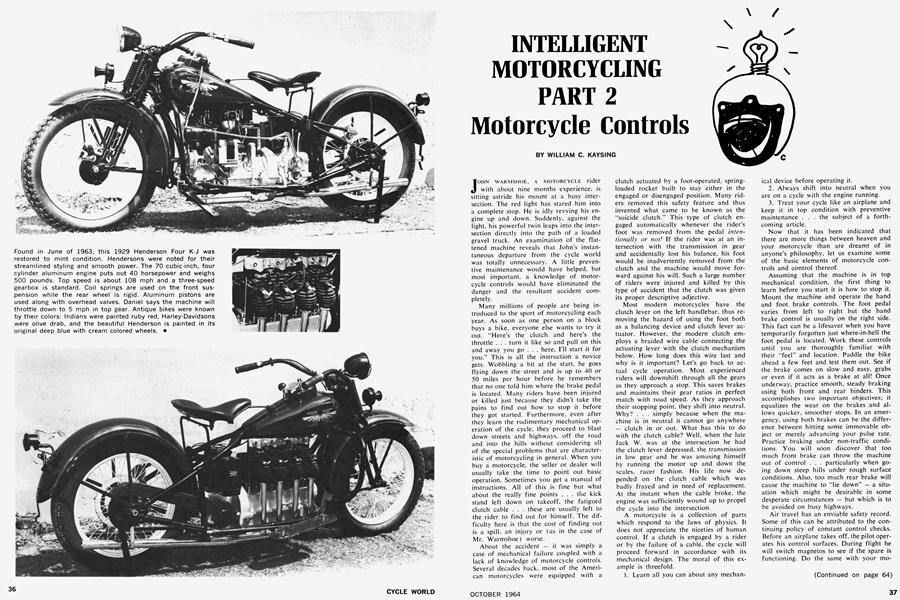

To summarize our discussion of controls on motorcycles, we can say that a bike is more like an airplane than a car. Almost anyone can hop in a four-wheeler and drive down the highway. Like an airplane, a motorcycle can bank, fly (for short distances), loop and will resent neglect of precise control without warning. Treat your cycle accordingly. Thoroughly understand each and every control of every machine that you ride even if you are only going for a short spin. A motorcycle will always respond the same ... it will give an excellent performance in return for excellent and intelligent control. •