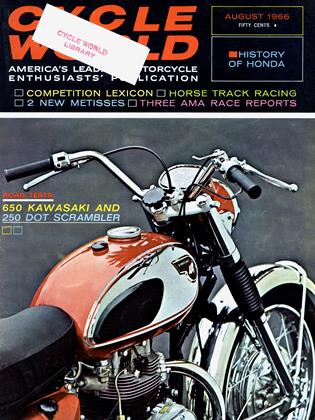

WEST GERMAN GRAND PRIX

HEINZ J. SCHNEIDER

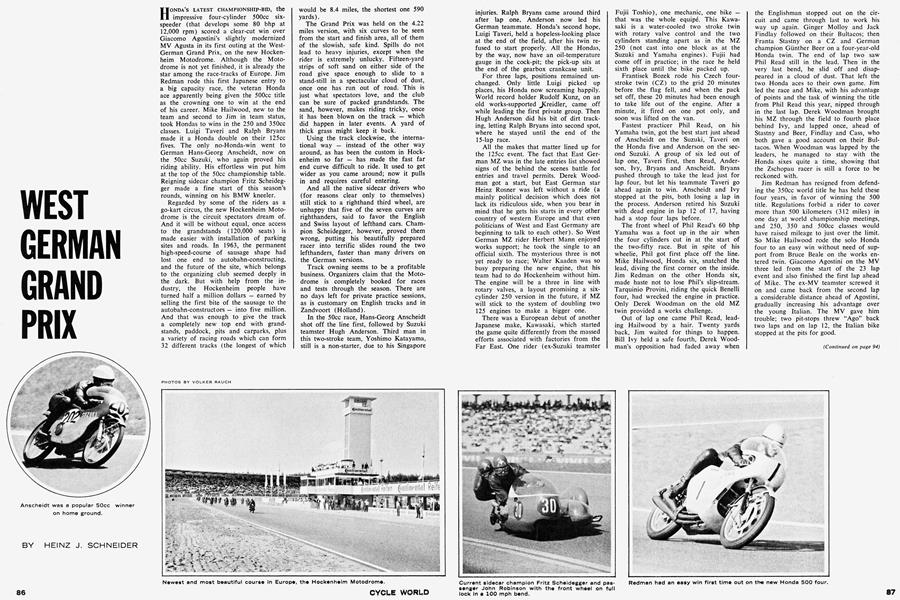

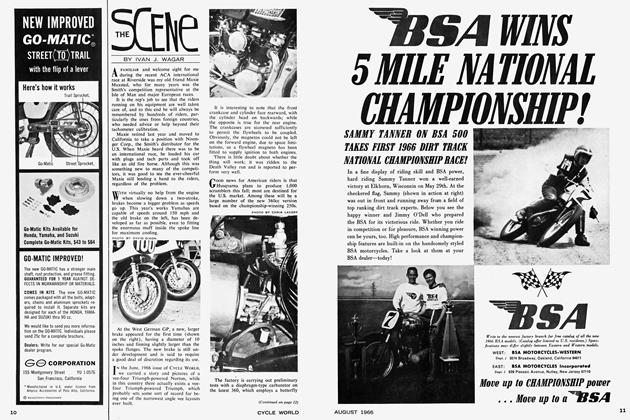

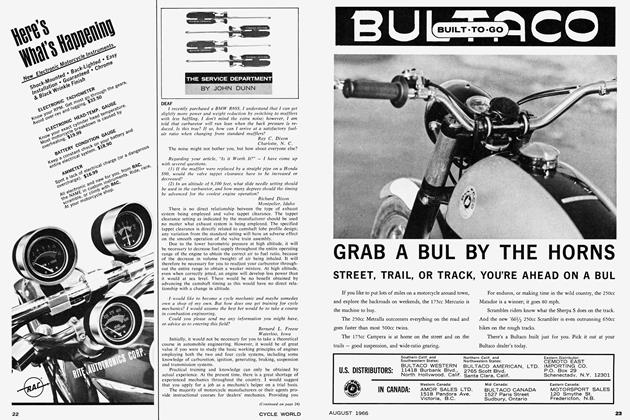

HONDA’S LATEST CHAMPIONSHIP-BID, the impressive four-cylinder 500cc sixspeeder (that develops some 80 bhp at 12,000 rpm) scored a clear-cut win over Giacomo Agostini’s slightly modernized MV Agusta in its first outing at the WestGerman Grand Prix, on the new Hockenheim Motodrome. Although the Motodrome is not yet finished, it is already the star among the race-tracks of Europe. Jim Redman rode this first Japanese entry to a big capacity race, the veteran Honda ace apparently being given the 500cc title as the crowning one to win at the end of his career. Mike Hailwood, new to the team and second to Jim in team status, took Hondas to wins in the 250 and 350cc classes. Luigi Taveri and Ralph Bryans made it a Honda double on their 125cc fives. The only no-Honda-win went to German Hans-Georg Anscheidt, now on the 50cc Suzuki, who again proved his riding ability. His effortless win put him at the top of the 50cc championship table. Reigning sidecar champion Fritz Scheidegger made a fine start of this season’s rounds, winning on his BMW kneeler.

Regarded by some of the riders as a go-kart circus, the new Hockenheim Motodrome is the circuit spectators dream of. And it will be without equal, once access to the grandstands (120,000 seats) is made easier with installation of parking sites and roads. In 1963, the permanent high-speed-course of sausage shape had lost one end to autobahn-constructing, and the future of the site, which belongs to the organizing club seemed deeply in the dark. But with help from the industry, the Hockenheim people have turned half a million dollars — earned by selling the first bite of the sausage to the autobahn-constructors — into five million. And that was enough to give the track a completely new top end with grandstands, paddock, pits and carparks, plus a variety of racing roads which can form 32 different tracks (the longest of which would be 8.4 miles, the shortest one 590 yards).

The Grand Prix was held on the 4.22 miles version, with six curves to be seen from the start and finish area, all of them of the slowish, safe kind. Spills do not lead to heavy injuries, except when the rider is extremely unlucky. Fifteen-yard strips of soft sand on either side of the road give space enough to slide to a stand-still in a spectacular cloud of dust, once one has run out of road. This is just what spectators love, and the club can be sure of packed grandstands. The sand, however, makes riding tricky, once it has been blown on the track — which did happen in later events. A yard of thick grass might keep it back.

Using the track clockwise, the international way — instead of the other way around, as has been the custom in Hockenheim so far — has made the fast far end curve difficult to ride. It used to get wider as you came around; now it pulls in and requires careful entering.

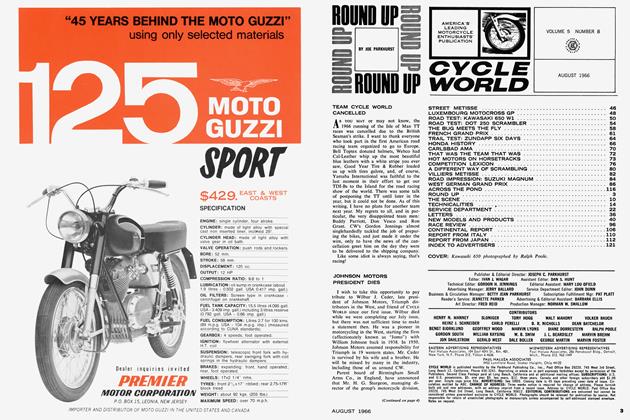

And all the native sidecar drivers who (for reasons clear only to themselves) still stick to a righthand third wheel, are unhappy that five of the seven curves are righthanders, said to favor the English and Swiss layout of lefthand cars. Champion Scheidegger, however, proved them wrong, putting his beautifully prepared racer into terrific slides round the two lefthanders, faster than many drivers on the German versions.

Track owning seems to be a profitable business. Organizers claim that the Motodrome is completely booked for races and tests through the season. There are no days left for private practice sessions, as is customary on English tracks and in Zandvoort (Holland).

In the 50cc race, Hans-Georg Anscheidt shot off the line first, followed by Suzuki teamster Hugh Anderson. Third man in this two-stroke team, Yoshimo Katayama, still is a non-starter, due to his Singapore injuries. Ralph Bryans carne around third after lap one. Anderson now led his German teammate. Honda’s second hope, Luigi Taveri, held a hopeless-looking place at the end of the field, after his twin refused to start properly. All the Hondas, by the way, now have an oil-temperature gauge in the cock-pit; the pick-up sits at the end of the gearbox crankcase unit.

For three laps, positions remained unchanged. Only little Luigi picked up places, his Honda now screaming happily. World record holder Rudolf Kunz, on an old works-supported JCreidler, came off while leading the first private group. Then Hugh Anderson did his bit of dirt tracking, letting Ralph Bryans into second spot, where he stayed until the end of the 15-lap race.

All the makes that matter lined up for the 125cc event. The fact that East German MZ was in the late entries list showed signs of the behind the scenes battle for entries and travel permits. Derek Woodman got a start, but East German star Heinz Rosner was left without a ride (a mainly political decision which does hot lack its ridiculous side, when you bear in mind that he gets his starts in every other country of western Europe and that even politicians of West and East Germany are beginning to talk to each other). So West German MZ rider Herbert Mann enjoyed works support; he took the single to an official sixth. The mysterious three is not yet ready to race; Walter Kaaden was so busy preparing the new engine, that his team had to do Hockenheim without him. The engine will be a three in line with rotary valves, a layout promising a sixcylinder 250 version in the future, if MZ will stick to the system of doubling two 125 engines to make a bigger one.

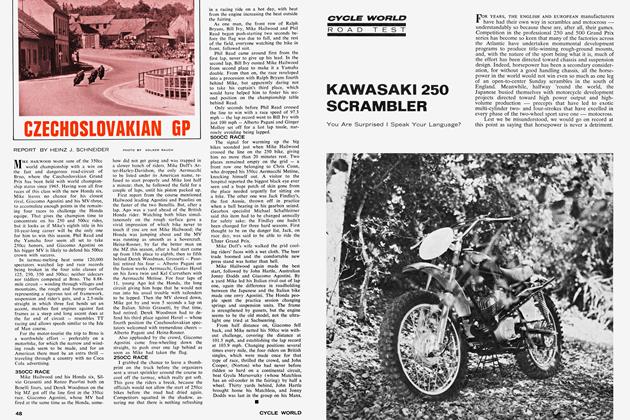

There was a European debut of another Japanese make, Kawasaki, which started the game quite differently from the massed efforts associated with factories from the Far East. One rider (ex-Suzuki teamster Fujii Toshio), one mechanic, one bike — that was the whole equipé. This Kawasaki is a water-cooled two stroke twin with rotary valve control and the two cylinders standing apart as in the MZ 250 (not cast into one block as at the Suzuki and Yamaha engines). Fujii had come off in practice; in the race he held sixth place until the bike packed up.

Frantisek Bozek rode his Czech fourstroke twin (CZ) to the grid 20 minutes before the flag fell, and when the pack set off, these 20 minutes had been enough to take life out of the engine. After a minute, it fired on one pot only, and soon was lifted on the van.

Fastest practicer Phil Read, on his Yamaha twin, got the best start just ahead of Anscheidt on the Suzuki, Taveri on the Honda five and Anderson on the second Suzuki. A group of six led out of lap one, Taveri first, then Read, Anderson, Ivy, Bryans and Anscheidt. Bryans pushed through to take the lead just for lap four, but let his teammate Taveri go ahead again to win. Anscheidt and Ivy stopped at the pits, both losing a lap in the process. Anderson retired his Suzuki with dead engine in lap 12 of 17, having had a stop four laps before.

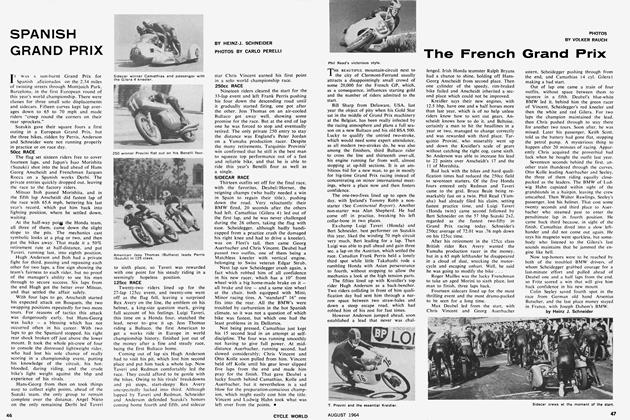

The front wheel of Phil Read’s 60 bhp Yamaha was a foot up in the air when the four cylinders cut in at the start of the two-fifty race. But in spite of his wheelie, Phil got first place off the line. Mike Hailwood, Honda six, snatched the lead, diving the first corner on the inside. Jim Redman on the other Honda six, made haste not to lose Phil’s slip-stream. Tarquinio Provini, riding the quick Benelli four, had wrecked the engine in practice. Only Derek Woodman on the old MZ twin provided a works challenge.

Out of lap one came Phil Read, leading Hailwood by a hair. Twenty yards back, Jim waited for things to happen. Bill Ivy held a safe fourth, Derek Woodman’s opposition had faded away when the Englishman stopped out on the circuit and came through last to work his way up again. Ginger Molloy and Jack Findlay followed on their Bultacos; then Franta Stastny on a CZ and German champion Günther Beer on a four-year-old Honda twin. The end of lap two saw Phil Read still in the lead. Then in the very last bend, he slid off and disappeared in a cloud of dust. That left the two Honda aces to their own game. Jim led the race and Mike, with his advantage of points and the task of winning the title from Phil Read this year, nipped through in the last lap. Derek Woodman brought his MZ through the field to fourth place behind Ivy, and lapped once, ahead of Stastny and Beer, Findlay and Cass, who both gave a good account on their Bultacos. When Woodman was lapped by the leaders, he managed to stay with the Honda sixes quite a time, showing that the Zschopau racer is still a force to be reckoned with.

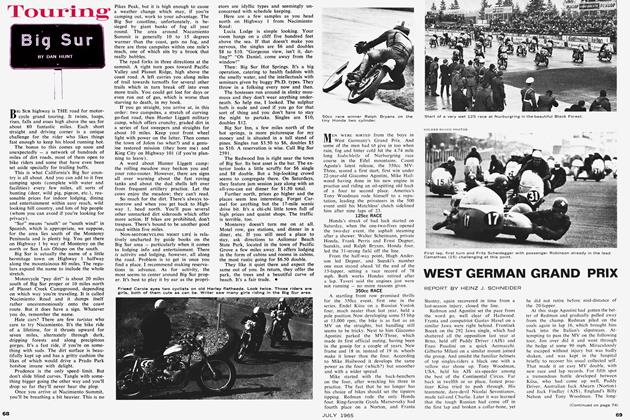

Jim Redman has resigned from defending the 350cc world title he has held these four years, in favor of winning the 500 title. Regulations forbid a rider to cover more than 500 kilometers (312 miles) in one day at world championship meetings, and 250, 350 and 500cc classes would have raised mileage to just over the limit. So Mike Hailwood rode the solo Honda four to an easy win without need of support from Bruce Beale on the works entered twin. Giacomo Agostini on the MV three led from the start of the 23 lap event and also finished the first lap ahead of Mike. The ex-MV teamster screwed it on and came back from the second lap a considerable distance ahead of Agostini, gradually increasing his advantage over the young Italian. The MV gave him trouble; two pit-stops threw “Ago” back two laps and on lap 12, the Italian bike stopped at the pits for good.

(Continued on page 94)

Provini used this chance to grab second place points on his new 350cc (genuine) Benelli four, Mike lapping him on the very last lap. Silvio Grassetti proved his Bianchi twin still competitive, beating Beale to take third. A similar Bianchi belonging to German Max Raab gave a sorry display of how a valuable bike can be misused for Sunday touring on fast people’s lines. Bianchi had sold out their racing stable last year, and ex-works rider Grassetti now is sponsored by an Italian factory which has bought the bikes for him.

Good old Franta Stastny (the end of his long career has often been predicted) and teammates Gustav Havel and Frantisek Bozek took their Czechoslovakian Jawas to places five to seven, and Derek Minter held up the English flag on the new Seeley-AJS. Thrills started late, as in the fight for ninth place, where privateers were in their own club. Canadian newcomer Rodger Beaumont finally got the best of never-aging Jack Ahearn, both on Nortons and young Stuart Graham (AJS), who is the son of the late Les Graham, MV-star of the fifties, who crashed fatally at the 1953 TT on the then hairy-to-ride 500 model. Stuart does not need his father’s name to gain popularity with the crowds. It is his racing — for the first time in the Continental Circus — that pays off. Fred Stevens on an AJS, instead of the Colin Lyster-sponsored Paton built for him in Italy (the bike is not yet finished), Tom Kirby’s Lewis Young and German champion Karl Hoppe followed, the six of them having swapped places every other mile until they finished in the given order.

With all the stupidity that only an organizer can muster, sidecars were started before the 500 solos, a method fortunately abandoned in most international events. Sidecars slide around the corners and therefore deposit rubber on the track, making the surface treacherous for solos. To make things messier, drivers try to keep their third wheels on the sand, mainly to cut the way short in the corners, and also to give the man behind a bit more trouble.

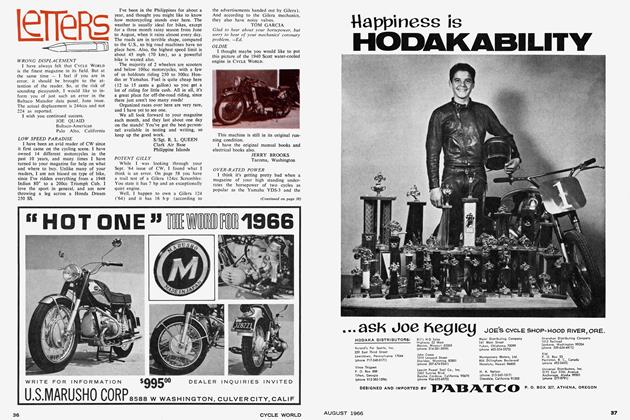

Ex-champion Max Deubel shot off the grid out of second row position to grab an early lead, ahead of title-holder Fritz Scheidegger, who cut inside Max in the first righthander to take first position, •which he never gave up again (in spite of his engine going rough at mid-distance of the 15-lap event). Max remained second, although he had not been given much of a chance after a disappointing practice session. He still drives his old outfit, which had won Walter Schneider his title in 1958, and he cannot make up his mind to engineer a modern one. A struggle developed for third place between Georg Auerbacher and England’s Colin Seeley on the Camathias-engined BMW. The ambitious German led most of the time, Colin often pushing through in the righthander after the starting-line, Georg regaining the lead in the sharp left-hander where his outfit was favored. Two laps from the end, however, he was shunted to the sand by lapped Swiss Hans-Peter Hubacher on his low BMW special. That gave Colin time for a safe third. Chris Vincent took fifth spot.

Hubacher, now in a position to draw attention not only for his pretty girl passenger, Renate Burghalter, but for driving and outfit as well, has gone to great expense building the first BMW in the game with 12-inch wheels all around, which involved cutting new gears for the bevel drive and casting special magnesium wheels. Former champion Helmuth Fath tried a come-back on a completely homemade special, propelled by the four cylinder engine he has built. With fascinating care, he goes over the engine with an electric temperature gauge after every few laps in practice, looking for hot spots. The outfit, a modern kneeler, has 12-inch wheels, and chain drive. It looks small and neat. However, the whole thing gives the impression of a lawnmower gone raving mad. Like his title-winning BMW, Fath’s new engine of an estimated 70 to 75 bhp, is equipped with fuel injection. The wide air intakes are made from glassfiber.

Big 500 racing has not really become much more interesting, now that Hondas have entered the field. Until last year, there was one superior bike, miles ahead of the opposition; now there are two, the Honda and the MV, separated by half a minute. Start of the race was delayed, as the marshals had to clear up the mess produced by the sidecars. The engines cooled off and John Cooper’s Norton refused to fire. Derek Minter’s Seeley Matchless went out after a lap with a leaking tank. With Redman’s Honda and Agostini’s MV far in the lead and after 20 laps of racing two laps ahead of third place, a tremendous scrap for third developed between Gyula Marsovszky, who finally succeeded, young Steward Graham and Lewis Young (all on Matchlesses) and Austrian Eddie Lenz (Norton), the four of them changing in the lead every lap until midway through the race. In the opening stages it had been a dozen riders in this bunch: Ian Burne, who later came off leading the group, Jack Findlay, Canadian Rodger Beaumont, Fred Stevens on the big Paton, Walter Scheimann and Helmuth Allner, who rides one of the few BMW RS models used for solo work, plus Kelvin Carruthers, who has done all the winning in his native Australia the past five years, and Jack Ahearn. The sight of these twelve equally fast bikes and almost equally good riders, dicing through the right-left-left-right-right-right sequence of curves, and the sound of the engines, multiplied by echoes from the grandstands, made one forget who led the race somewhere out in the blue.

Jack Ahearn and Walter Scheimann later dropped back — all the others having retired — and were caught by Dan Shorey. Walter even had to let Billie Nelson go by. But he could take it easy; his only rival for German championship points, Karl'Hoppe on a borrowed Matchless, was one more lap behind. Texas rider Byron Allen Black was entered, but did not turn up. He was said to be working on a Matchless in England.