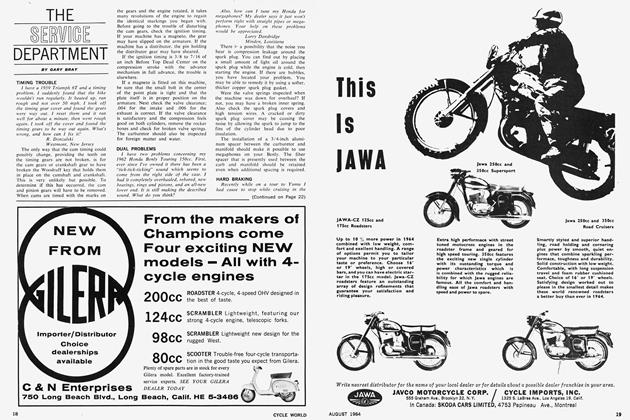

The French Grand Prix

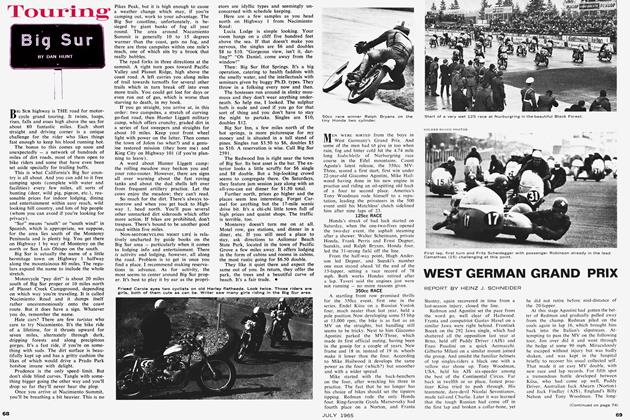

Phil Read's victorious style.

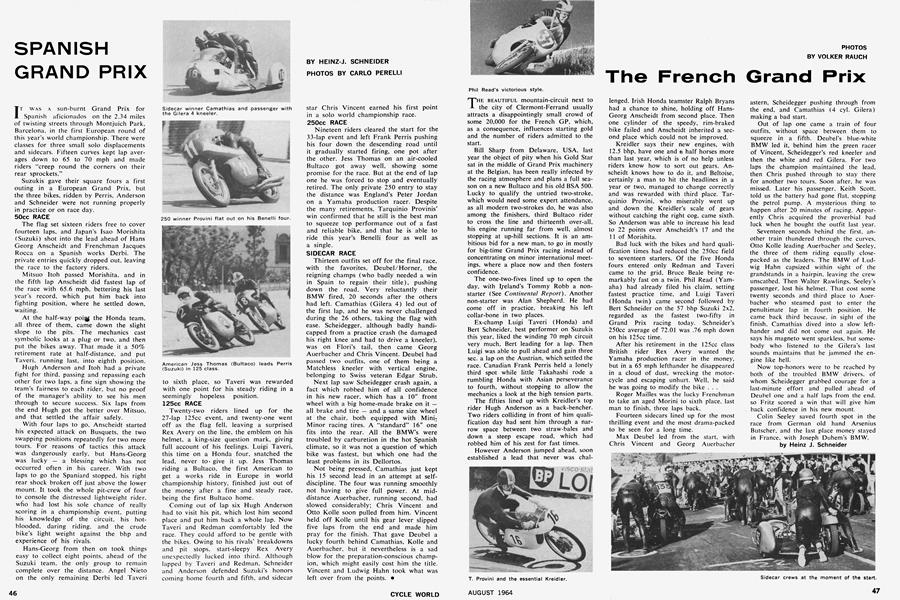

THE BEAUTIFUL mountain-circuit next to the city of Clermont-Ferrand usually attracts a disappointingly small crowd of some 20,000 for the French GP, which, as a consequence, influences starting gold and the number of riders admitted to the start.

Bill Sharp from Delaware, USA, last year the object of pity when his Gold Star sat in the middle of Grand Prix machinery at the Belgian, has been really infected by the racing atmosphere and plans a full season on a new Bultaco and his old BSA 500. Lucky to qualify the untried two-stroke, which would need some expert attendance, as all modern two-strokes do, he was also among the finishers, third Bultaco rider to cross the line and thirteenth over-all, his engine running far from well, almost stopping at up-hill sections. It is an ambitious bid for a new man, to go in mostly for big-time Grand Prix racing instead of concentrating on minor international meetings, where a place now and then fosters confidence.

The one-two-fives lined up to open the day, with Iceland's Tommy Robb a nonstarter (See Continental Report). Another non-starter was Alan Shepherd. He had come off in practice, breaking his left collar-bone in two places.

Ex-champ Luigi Taveri (Honda) and Bert Schneider, best performer on Suzukis this year, liked the winding 70 mph circuit very much, Bert leading for a lap. Then Luigi was able to pull ahead and gain three sec. a lap on the Austrian, which settled the race. Canadian Frank Perris held a lonely third spot while little Takahashi rode a rumbling Honda with Asian perseverance to fourth, without stopping to allow the mechanics a look at the high tension parts.

The fifties lined up with Kreidler's top rider Hugh Anderson as a back-bencher. Two riders colliding in front of him qualification day had sent him through a narrow space between two straw-bales and down a steep escape road, which had robbed him of his zest for fast times.

However Anderson jumped ahead, soon established a lead that never was challenged. Irish Honda teamster Ralph Bryans had a chance to shine, holding off HansGeorg Anscheidt from second place. Then one cylinder of the speedy, rim-braked bike failed and Anscheidt inherited a second place which could not be improved.

Kreidler says their new engines, with 12.5 bhp, have one and a half horses more than last year, which is of no help unless riders know how to sort out gears. Anscheidt knows how to do it, and Beltoise, certainly a man to hit the headlines in a year or two, managed to change correctly and was rewarded with third place. Tarquinio Provini, who miserably went up and down the Kreidler's scale of gears without catching the right cog, came sixth. So Anderson was able to increase his lead to 22 points over Anscheidt's 17 and the 11 of Morishita.

Bad luck with the bikes and hard qualification times had reduced the 250cc field to seventeen starters, Of the five Honda fours entered only Redman and Taveri came to the grid, Bruce Beale being remarkably fast on a twin. Phil Read (Yamaha) had already filed his claim, setting fastest practice time, and Luigi Taveri (Honda twin) came second followed by Bert Schneider on the 57 bhp Suzuki 2x2, regarded as the fastest two-fifty in Grand Prix racing today. Schneider's 250cc average of 72.01 was .76 mph down on his 125cc time.

After his retirement in the 125cc class British rider Rex Avery wanted the Yamaha production racer in the money, but in a 65 mph lefthander he disappeared in a cloud of dust, wrecking the motorcycle and escaping unhurt. Well, he said he was going to modify the bike ...

Roger Mailles was the lucky Frenchman to take an aged Morini to sixth place, last man to finish, three laps back.

Fourteen sidecars lined up for the most thrilling event and the most drama-packed to be seen for a long time.

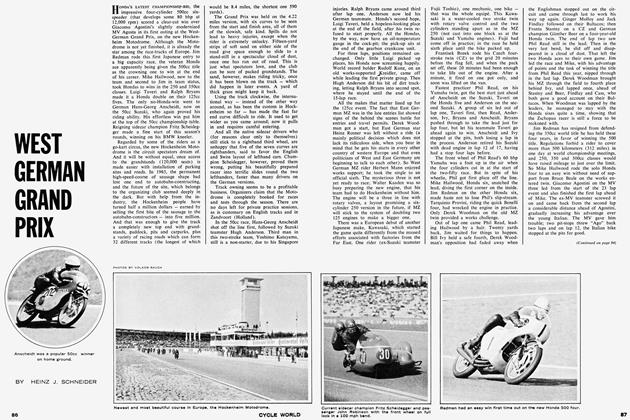

Max Deubel led from the start, with Chris Vincent and Georg Auerbacher astern, Scheidegger pushing through from the end, and Camathias (4 cyl. Gilera) making a bad start.

Out of lap one came a train of four outfits, without space between them to squeeze in a fifth. Deubel's blue-white BMW led it, behind him the green racer of Vincent, Scheidegger's red kneeler and then the white and red Gilera. For two laps the champion maintained the lead, then Chris pushed through to stay there for another two tours. Soon after, he was missed. Later his passenger, Keith Scott, told us the battery had gone flat, stopping the petrol pump. A mysterious thing to happen after 20 minutes of racing. Apparently Chris acquired the proverbial bad luck when he bought the outfit last year.

Seventeen seconds behind the first, another train thundered through the curves. Otto Kolle leading Auerbacher and Seeley, the three of them riding equally closepacked as the leaders. The BMW of Ludwig Hahn capsized within sight of the grandstands in a hairpin, leaving the crew unscathed. Then Walter Rawlings, Seeley's passenger, lost his helmet. That cost some twenty seconds and third place to Auerbacher who steamed past to enter the penultimate lap in fourth position. He came back third because, in sight of the finish, Camathias dived into a slow lefthander and did not come out again. He says his magneto went sparkless, but somebody who listened to the Gilera's last sounds maintains that he jammed the engine like hell.

Now top-honors were to be reached by both of the troubled BMW drivers, of whom Scheidegger grabbed courage for a last-minute effort and pulled ahead of Deubel one and a half laps from the end. so Fritz scored a win that will give him back confidence in his new mount.

Colin Seeley saved fourth spot in the race from German old hand Arsenius Butscher, and the last place money stayed in France, with Joseph Duhem's BMW.

Heinz J. Schneider

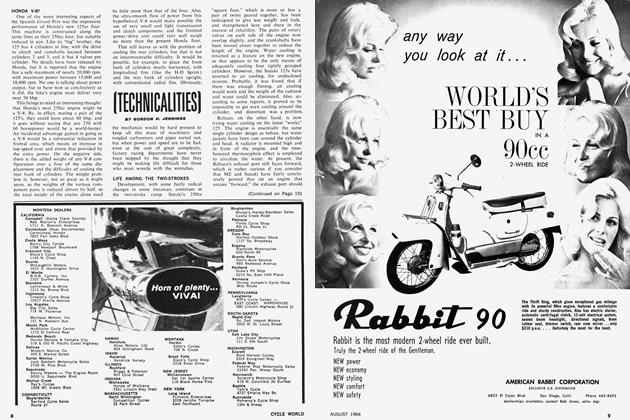

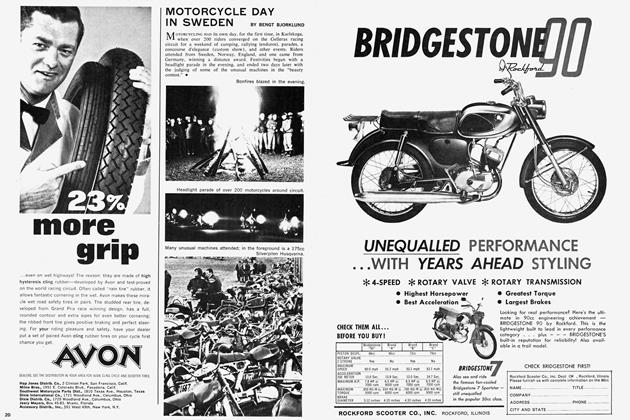

The pleasant,

ranch-style house in the new subdivision of Pinole, Calif.,

looks perfectly normal from the outside. It's not until you enter the garage and see the walls hung with motorcycle parts and the assorted racing machines in various states of completion,

that the home of Dick Mann,

AMA National No. 1 competition rider, looks any different frçm the home of Joe Doakes, office clerk.

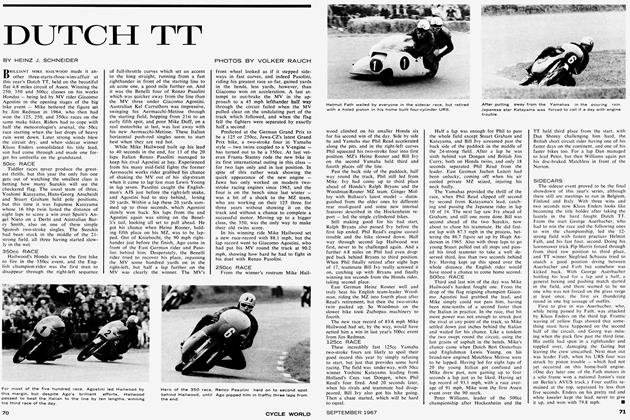

A pair of bright blue Matchless gas tanks and a few less identifiable types are hung over rafters, and a battery of cabinets and racks on the walls overflow with parts and supplies. In a corner is a pile of new and used tires, and a huge red tool chest dominates the floor. It is a Saturday afternoon, and Mann and his close friend Dick Dorresteyn are preparing machines for the evening's competition at San Francisco's Champion Speedway. The task at hand is an air cleaner mount, which Mann is bolting securely in place.

"The amount of work I do before a race depends on how much time I have," the red-haired racer-tuner shrugs. "This bike is just left over from last year. I can work on it right up to race time or I could start it now and go."

The mount securely tightened, Mann put away the wrench and began rummaging in a box for the air cleaner.

"You can run three or four races before you have to do a top end on a bike (a ring and valve job)," he said over his shoulder. "For a long race, a National or a road race, you pretty near do a complete job every time you take it out."

(The careful break-in period of a touring machine is avoided in a racing engine by assembling it to tolerances that are less close.)

"Probably the first time it runs," Mann said, "will be on the track."

Mann's build is slight, but wiry, and he

Dick Dorresteyn and Dick Mann load up their machines and head for the track. moves — or you imagine he moves with a sureness and grace.

He speaks quietly, but with authority, and has an amazing store of knowledge about cycles, riders, and competition throughout the world. He is very cooperative, and is happy to speak his mind on a variety of subjects.

A natural conversational opener was the increased popularity of two-wheeled transportation in the United States these days, a subject which Mann, both a rider and a professional motorcycle mechanic in a Richmond, Calif., cycle shop, is very interested in.

"All types of people watch races now,"f he says. "Once they see them they generally like them. The problem is to get them to go the first time.

"Lots of people who never would have bought 'noisy' 'dirty' motorcycles have bought little Hondas. Then they see a motorcycle race advertised, get curious and go. They are usually happy to find when they get there that the noisy minority group isn't representative of the sport."

The mount carefully tightened, Mann slipped the air cleaner over the shiny mouth of the huge racing carburetor, fastened it with a thick black rubber band doubled several times, and then proceeded to check the oil level in the front forks.

"Track racing," he offered, "is so simple it's complicated.

"It's just a big circle, so all the little intricate details are important all out of proportion. In a road race when you have 10 or 15 different corners, there are just that many more places where you can do better than the next guy. But at a track race, it's just that one thing turning left."

Mann stopped talking for a moment, intent on the oil pouring into the fork leg. Then he put down the can and bounced the front of the machine to test the springiness of the forks.

"Most of the guys out there on the track are pretty equal," he resumed, "and the bikes have just about as much speed, but mostly it's a race between tires. The guy who has the best tires, the most traction, the right air pressure or the right amount worn off — has the advantage.

"Most of it is conditioned reflexes. Whenever an opportunity comes up you have to make a decision real fast, or else you end up trailing the guy another lap.

(Continued on page 63)

"Your speed in the strai-ght depends a lot on how well you make it out of the corner — how much traction you have. From the stands you can see one man right on the tail of another, and they are both going exactly the same speed. But then one man can come out of the turn better than the first, and that spurt you see is the better turn, making itself felt in the straightaway."

To the question of "what about brakes?" Mann's reply is: "You rarely need them. Because you are just turning left as fast as you can, when something happens unexpectedly — you slide or something — the bike automatically goes right. The same thing happens when you put on your brakes. It's hard to make yourself just stay in the groove and keep racing when a pile-up happens, but that's actually the safest thing to do.

"That's why we don't like to race with the novices. It takes a rider two or three years to develop the skills he needs on the track. If you waver or make a mistake, you'll lose it.

"About the only time you wish you had brakes is when one man has gone down and several others have piled into him and the track is blocked. When you're bearing down on something like that, they'd be handy."

Twenty-nine years old, Mann began riding when he bought a BSA Bantam in 1949, to deliver newspapers.

He first raced in endurance runs, "about the only kind of competition there was back in those days," in 1949.

Slogging through the mud seems to have had a lasting effect, for "Bugsy" as he is known to many fans, still has an awe-inspiring reputation for eating up the opposition in rough scrambles contests.

Popular scuttlebutt in the pits has it that the rougher it is, the better Mann likes it. Talking to him personally, one gets the impression that the legend is pretty accurate, for Mann doesn't hesitate to make his preference for rougher scrambles known.

"Scrambles have really gone downhill," he said, returning the oil can to its shelf. "It's just a copy of track racing now. They have everything like professional racing except the professionals.

"As a result, no one's learning to ride in the rough anymore.

"It's gotten so far out of hand that even the people who run the events are changing it. In Europe and on the east coast, though, the scrambles are still really scrambles."

Next question was about the types of tracks used in cycle racing, and the redhaired champion replied that he liked horse tracks.

"Horse tracks are usually long and narrow, and covered with a soft loamy dirt. Car tracks are usually made of imported clay, big round things. I didn't start out liking horse tracks, I just ended up doing better on them."

With the primary chain case filled to the proper level, Mann had just returned the oil can to a case in the corner when things were interrupted by the arrival of 7-yearold Diane Mann, who wanted help from Daddy on some schoolwork.

Obligingly, Mann stopped working and rendered the required assistance, then sent his blonde little daughter back to the house.

"She's a real fan," he smiled, wiping his hands on a red shop rag. "Goes to the races and really knowns what's going on."

Dick and his wife Jo Ann have another child, nine-month-old Scott. "Jo Ann does not mind my racing," he says, "it's being away from home so much."

Almost finished now, Mann began gathering wrenches and spare parts to take to the track. Still another rear sprocket took its place in the orange chest, and this prompted a question about gearing for the track.

"Gear ratios are very changeable," Mann answered. "I go by what I ran the last time, then I end up changing a few times at the track, usually."

A box of spark plugs brought up the AMA Daytona road race, which Mann failed to finish because of an engine failure.

"I'd sure like to see better press coverage of races," he said. "The wire service report from Daytona said I dropped out because of spark plug failure. And since I'm sponsored by NGK Plugs, I wasn't too happy about that. I guess the problem is these guys are up in the stands and they have to write something, so they write without checking."

Though he didn't finish the race, Daytona provided Dick with a moral victory of sorts, as the champion's long dispute with the AMA over the "not stock" Matchless CSR racing frame was finally resolved.

"The AMA okayed the frame," Mann reported, "but by that time I was already entered on a Norton. Everett Brashear rode the Matchless, and placed sixth.

"I don't really know what happened to my machine. It started making noises on the right side, then it quit. I didn't get a chance to take it apart, so I never found out what happened."

As he talked, Mann unscrewed the oil filler cap and began pouring in the familiar-smelling castor oil. He doesn't drain the machine after each race, he said, because of the improved quality of modern castor oils.

"They have a lot of additives in them now," he said, putting the can down. "They don't gum up like they used to — not so bad anyhow."

There was time for one more question, so I asked one that had been bothering me for some time: What factors make two identical engines perform differently?

"I don't know," Mann answered. "I can build two or three engines exactly the same and one will run better than the others."

He patted the aged leather seat of the BSA, and smiled as if he were thinking of a private joke. "They treat you bad if you don't treat them good," he said.

"They not only let you down, they put you down."