A.M.A. DAYTON A NATIONALS

JOE PARKHURST

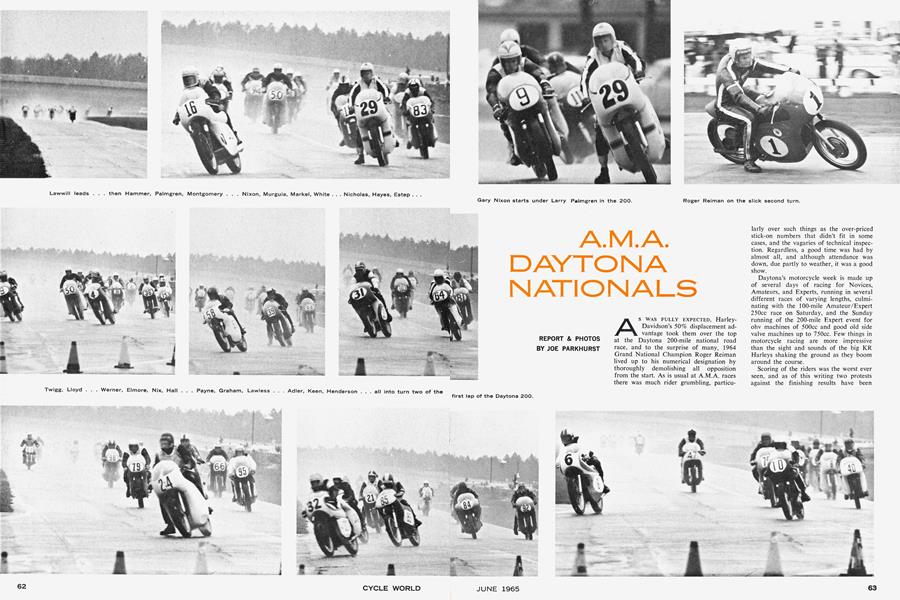

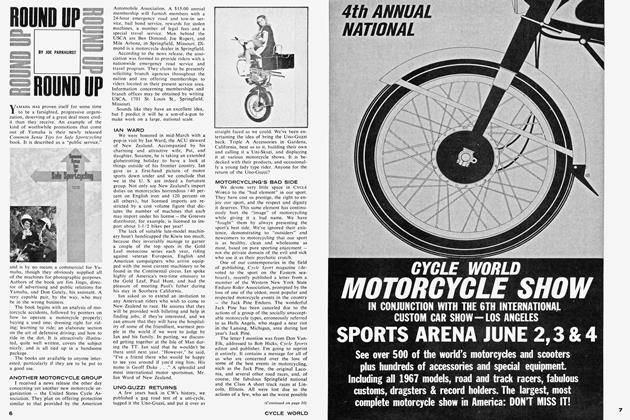

As WAS FULLY EXPECTED, HarleyDavidson's 50% displacement advantage took them over the top at the Daytona 200-mile national road race, and to the surprise of many, 1964 Grand National Champion Roger Reiman lived up to his numerical designation by thoroughly demolishing all opposition from the start. As is usual at A.M.A. races there was much rider grumbling, particularly over such things as the over-priced stick-on numbers that didn't fit in some cases, and the vagaries of technical inspection. Regardless, a good time was had by almost all, and although attendance was down, due partly to weather, it was a good show.

Daytona's motorcycle week is made up of several days of racing for Novices, Amateurs, and Experts, running in several different races of varying lengths, culminating with the 100-mile Amateur/Expert 250cc race on Saturday, and the Sunday running of the 200-mile Expert event for ohv machines of 500cc and good old side valve machines up to 750cc. Few things in motorcycle racing are more impressive than the sight and sounds of the big KR Harleys shaking the ground as they boom around the course.

Scoring of the riders was the worst ever seen, and as of this writing two protests against the finishing results have been lodged that we know of, perhaps more. Scorers were placed in a building at one of the fastest parts of the course, contrary to A.M.A. rules, making identification of the riders almost impossible. Topping that off was the fact that the promoters apparently did not provide any official scorers, instead relying upon each rider to furnish his own. Little imagination is necessary to envision the confusion and numerous opportunities for error, both accidental and intentional.

Weather varied from hot and humid to cold and rainy. For the first time ever an A.M.A. National was started in the rain when the huge field of big machines began the 200. Race organization was just fair. Few events went off as scheduled but all did ultimately get going, and that, after all, is why all those motorcycles were there. The races were again run on the 3.81-mile paved and banked track, using the largest part of the famous Daytona Tri-Oval. As before, this long "straight" was a big advantage for the 750cc bikes since the emphasis continues to be on power, rather than rider ability. We do not mean to detract a thing from Reiman's and Dick Mann's stunning victories, but facts are facts and at least this magazine is a little bit tired of the old run-around.

Heartbreaks, frustrations and disappointments took their parts as they always do in the racing game. West coast road racing exponent Frankie Scurria, riding with his leg only partially healed from a spill at

Willow Springs came a cropper early in the 250cc Amateur/Expert event and was seriously injured. The simple fact was he should not have been allowed to compete. Stellar rider Dick Hammer was sidelined for the 250 event; his contract with Triumph unfortunately forbade his competing on any other make, regardless of class. Much ado was made over the new 250cc Ducatis to be ridden by Tony Woodman and Jim and Kenny Hayes. They were finally accepted as being legal (though bearing little resemblance to Class C machines), after a ding-dong battle between the sponsors and Rod Coates of the A.M.A.'s Technical Committee. A.M.A. Executive Secretary Lin Kuchler was finally called to settle the dispute; it seems as though he had accepted their entry without telling anyone else about it until almost too late.

We were happy to see them accepted. They represent as good a reason as any to see the unrealistic and generally ignored Class C rule abandoned. It would be far simpler, and closer to what is actually being practiced to simply allow any and everything be done to a machine as long as the engine remains an example of a manufactured product and within a displacement limitation that is fair to all. The Yamaha victory in the 250cc Amateur /Expert 100-mile race was so stunningly conclusive, we are not being too guilty of pessimism to wonder what the A.M.A. will do about them. We recommend that since a two-stroke actually mounts its "valves" in the side, it should be given a 50% bias over the overhead valve 250cc machines and allowed to increase its displacement to 375cc! How's that for logic?

100-MILE AMATEUR RACE Wayne Cook of Richmond, Va., on his Harley-Davidson fought every inch of the way with young Ed Moran from New Jersey on the "official" BSA entry, to first place by about 125 feet. His average of 92.430 was almost 3 mph faster than last year's average. Far back in the pack was James Dour on a Matchless. Cook started on the pole, since he qualified fastest of the field, but the lead changed often between Mike Bonnell's Triumph and Ken Ridder on a Harley. Cook and Moran battled only during the closing laps and staged a finish rarely seen at the likes of Daytona.

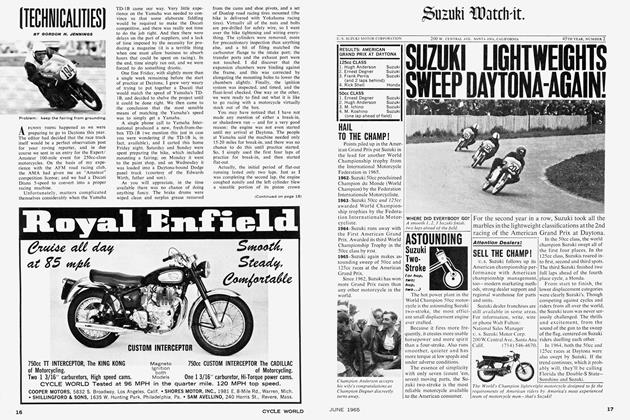

250 AMATEUR/EXPERT 100-MILE Few races see the kind of total rout dealt by Yamaha riders as in the 100-mile Amateur/Expert event. Eight out of ten of the first finishers were Yamaha-mounted. So complete was their victory that only the mightiest Harley-Davidson "factory" entries of Mert Lawwill and George Roeder were able to even stay in the same race, finishing 5th and 6th. Capping it all was the astounding 131 mph practice lap turned by Tony Murphy, A.F.M. star from California. This speed was only a scant 2 mph under those achieved bv the fastest 750's qualifying for the 200-miler. We note with disdain that the 250's did not qualify in the truest sense of the word since positions on the grid for the race were earned by placing in one of three 3-lap heat races. On the surface this is fine, but how did they "earn" their starting positions in the heats? By drawing for them, we are told.

Biggest disappointments were the factory prepared Ducatis, ridden by Tony Woodman, probably the best Eastern American road racer, and Kenny and Jim Hayes, those tigers from Tennessee. Hopelessly outclassed, they indicated a potential far beyond their demonstrated performance and we detect another taste of European tuners underestimating the abilities of the American tuners and riders again. Montesa distributors showed up with their F.I.M. Sebring 3rd place winning 250's; one ran out of gas, the other suffered an unknown malady.

Grand National Champion Dick Mann took the lead in the fifth lap and was never pressed. He averaged 91.606 mph for the 100 miles, over 3 mph faster than Dick Hammer's 1964 H-D victory speed of 88.455 mph. Gary Nixon from Wheaton, Md., and Buddy Elmore from Texas, came home behind Mann; this was Elmore's first year as an Expert.

Tony Murphy was one who was expected to be the victor, but his Yamaha was not up to the speeds being achieved by the leaders. An ironic twist to the situation was the switching of engines done in Murphy's machine. He gave his "tired" power plant to Dick Mann, who did not even race in a heat [sic], and then Mann calmly proceeded to drive him into the ground with it, leaving Murphy to come home in a lowly 10th spot. Another Yamaha rider, Robert Winters of Fort Smith, Arkansas, an Amateur, ran in the front five for 16 laps before dropping out with ignition trouble.

Orin Hall's pair of remarkable Parillas were again on hand, ridden by A. F. M. men Ron Grant and Frankie Scurria, both from California. For the first time in their history neither was competitive. Scurria battled furiously for many laps, before retiring. Grant's machine failed in his heat race and did not start the main event. Ronnie Rail from Mansfield, Ohio, fast becoming one of the A.M.A.'s real road racing stylists, brought his outclassed Honda into 17th place. Young violinist Jody Nicholas riding a Bultaco 250 (sole example in this country at the time), rode beautifully most of the race but joined the ranks of non-finishers. Among the illustrious names of racing in the non-finishers category was Roger Reiman whose Aermacchi Harley-Davidson failed, and Bart Markel, also H-D Sprint mounted.

DAYTONA 200 EXPERT EVENT Strangest sight at the start of the famous Daytona 200 was rain, real rain, and lots of it. Most were surprised the race was even begun. Although a customary practice in European motorcycle and car racing for years, running in the wet was entirely new to almost every man on the overcrowded grid. One to whom it was not to be a problem at all was Ron Grant who raced often in his native England before coming to California and the A.F.M. Grid positions were given according to qualifying speeds, strangely enough, not speeds demonstrated on the race course, but rather on the big, virtually straight Daytona Tri-Oval. With tonguein-cheek we point out again that this means machines with the most power start the race in the most favorable positions. This, instead of machines with the best times posted on the track according to acceleration, top speed, braking, and pure rider ability! We are as tired of making an issue of this as we are sure some people are of seeing us do it.

Aces-in-the-hole were evident though. Several Triumphs looked awfully good, particularly Dick Hammer on the Johnson Mtrs. entry who qualified at 132.705. Mel Lacher's Harley led the parade with 133.333, followed by George Roeder's H-D time of 133.097 mph. Don Vesco, riding the often-disowned G-50 model Matchless he so successfully races in A.F.M. races, was the nearest qualifier on that make with a time of 129.926 in fifth position. Ralph White, late of H-D fame, riding one of three Matchless entries of Tom Hansen, qualified at 129.348 in 8th fastest spot. Last year's man-of-thehour Gary Nixon on the Baltimore Triumph was way down the line with 127.425 mph.

But, even as the race proved, qualifying times had little to do with the running of the race. Roger Retman took his Harlev-Davidson KR into the lead on the 15th laD — foot-down, dirt tracking it on the slippery corners and going like the wind when he could. Rain cut the visibility to nothing at times, and let up only for a few minutes of the total race. First laps were painfully slow as the riders learned how to ride under the difficult conditions, and as lap numbers mounted, so did speeds. Though the race average was onlv 90.041 mph, considering how slippery and miserable things were it was a great credit to the superb ridine demonstrated bv the front runners. We can't really call what we saw a road race, it was more like a series of drag strips with some dirt-stvle TT corners connecting them. Reiman's win, his third Daytona, earned him $3,250, a tidy sum in motorcycle racing, but far under what he deserved when gauged in terms of car racing nurses.

(Continued on page 108)

Mert Lawwill from San Francisco, who skv-rocketed into his second year as an Exnert, was only 40 seconds behind Reiman on another Harley KR. Third spot went to George Montgomery on a Triumph, followed by Gary Nixon's Triumoh and Dick Mann's Matchless, though in the light of the poorly handled scoring we heard several versions of who "really" won the other positions. We know that Nixon made two pit stops, and Mann only one, yet Nixon finished ahead. We relate this not to discredit either rider, only to cite the deplorable results of the haphazard scoring system.

The lead changed hands over four times. Markel on the H-D led the first lap and ran second on the 45th but dropped out. Dick Hammer on the Triumph was out front on lap three and held it until Reiman powered by him on the 14th. Jody Nicholas brought his wellsponsored BSA into 8th position after a beautiful demonstration of feet-up-in-thewet cornering all the way. Buddy Elmore rode his Triumph to 6th spot. Tony Murguia rode his Harley in third position through the 27th lap, and then dropped out. Ralph White's Team Hansen Matchless G-50, Daytona winner in 1963, was in fifth position when he spilled and dropped out of the race on the 24th lap.

One hundred and six riders started the 100-mile Amateur/Expert event; several spills occurred due partly to the large number of riders. We would like to see the A.M.A. emulate the F.I.M. and limit the number of starters to, say, 60 to 80. It would seem a far safer number and would not detract a bit from the race. Local Daytona newspapers of course prefer the large numbers; it gives their ghoulish photographers an excellent opportunity to shoot all of the spills, and believe us, every single one of them is used daily. Traffic is so dense in the first few laps that a spilled rider cannot be avoided, hence the serious accident in the early stages of the 250 race. We don't mean to recommend pampering racers, only that the racing be made a little safer for the riders. •

View Full Issue

View Full Issue