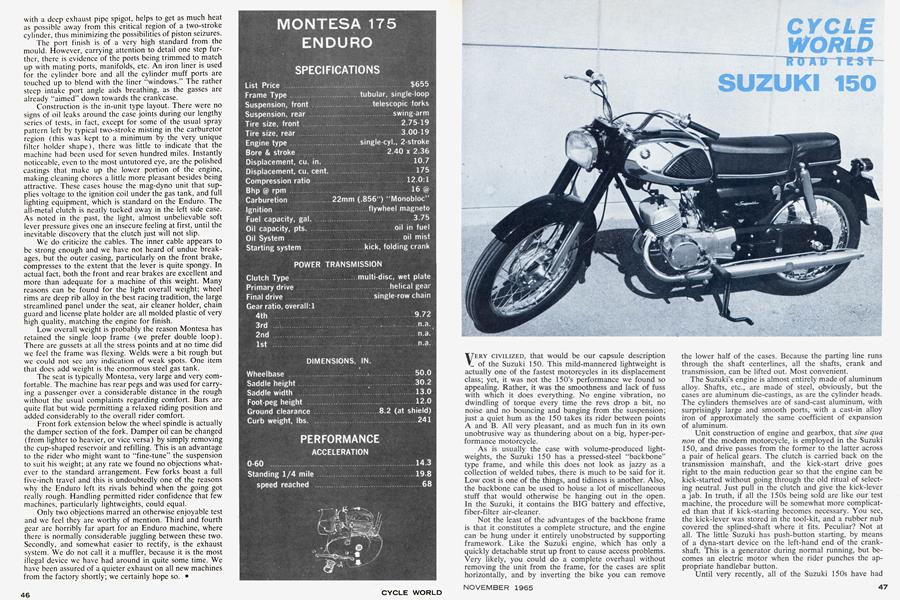

SUZUKI 150

CYCLE WORLD ROAD TEST

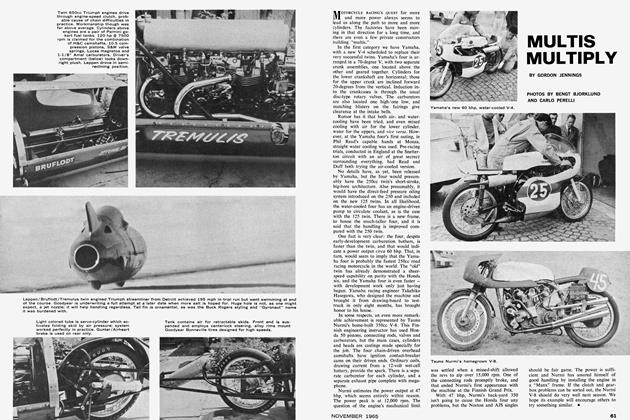

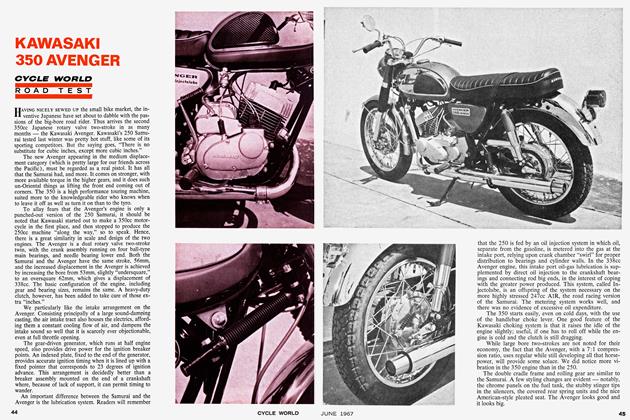

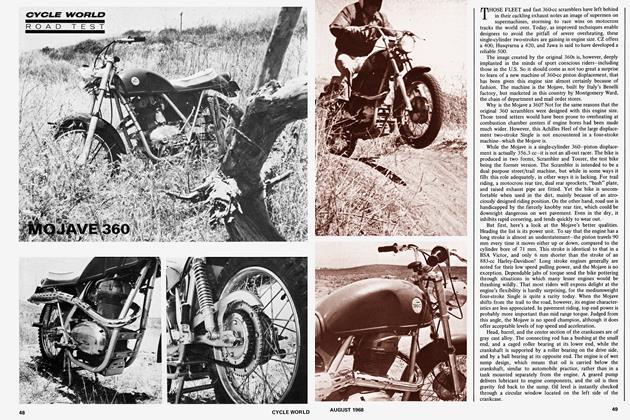

VERY CIVILIZED, that would be our capsule description of the Suzuki 150. This mild-mannered lightweight is actually one of the fastest motorcycles in its displacement class; yet, it was not the 15O's performance we found so appealing. Rather, it was the smoothness and lack of fuss with which it does everything. No engine vibration, no dwindling of torque every time the revs drop a bit, no noise and no bouncing and banging from the suspension; just a quiet hum as the 150 takes its rider between points A and B. All very pleasant, and as much fun in its own unobtrusive way as thundering about on a big, hyper-performance motorcycle.

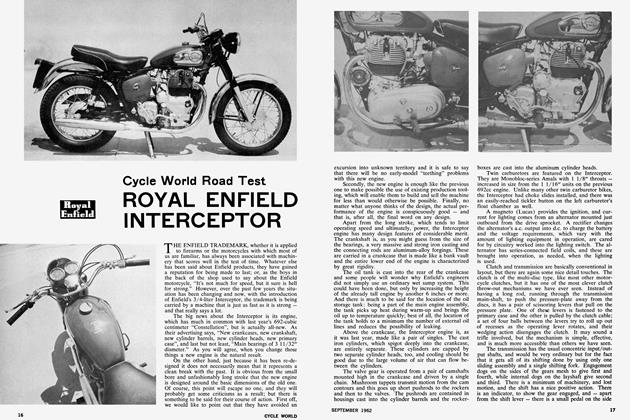

As is usually the case with volume-produced lightweights, the Suzuki 150 has a pressed-steel "backbone" type frame, and while this does not look as jazzy as a collection of welded tubes, there is much to be said for it. Low cost is one of the things, and tidiness is another. Also, the backbone can be used to house a lot of miscellaneous stuff that would otherwise be hanging out in the open. In the Suzuki, it contains the BIG battery and effective, fiber-filter air-cleaner.

Not the least of the advantages of the backbone frame is that it constitutes a complete structure, and the engine can be hung under it entirely unobstructed by supporting framework. Like the Suzuki engine, which has only a quickly detachable strut up front to cause access problems. Very likely, you could do a complete overhaul without removing the unit from the frame, for the cases are split horizontally, and by inverting the bike you can remove the lower half of the cases. Because the parting line runs through the shaft centerlines, all the shafts, crank and transmission, can be lifted out. Most convenient.

The Suzuki's engine is almost entirely made of aluminum alloy. Shafts, etc., are made of steel, obviously, but the cases are aluminum die-castings, as are the cylinder heads. The cylinders themselves are of sand-cast aluminum, with surprisingly large and smooth ports, with a cast-in alloy iron of approximately the same coefficient of expansion of aluminum.

Unit construction of engine and gearbox, that sine qua non of the modern motorcycle, is employed in the Suzuki 150, and drive passes from the former to the latter across a pair of helical gears. The clutch is carried back on the transmission mainshaft, and the kick-start drive goes right to the main reduction gear so that the engine can be kick-started without going through the old ritual of selecting neutral. Just pull in the clutch and give the kick-lever a jab. In truth, if all the 150s being sold are like our test machine, the procedure will be somewhat more complicated than that if kick-starting becomes necessary. You see, the kick-lever was stored in the tool-kit, and a rubber nub covered the splined-shaft where it fits. Peculiar? Not at all. The little Suzuki has push-button starting, by means of a dyna-start device on the left-hand end of the crankshaft. This is a generator during normal running, but becomes an electric motor when the rider punches the appropriate handlebar button.

Until very recently, all of the Suzuki 150s have had single-leading shoe brakes. Our test bike is one of the last of this type. Henceforth, the 150 will have doubleleading actuation for the front brake, which will not do anything for its fade-resistance or anything like that but will at least have the effect of reducing the amount of effort required at the front brake lever. There was nothing about our test bike to indicate the brakes needed any improving, but as long as a slightly better brake is going to be offered at no increase in price, who are we to offer objections?

Possibly better brakes would be handy when carrying a passenger, which the 150 will do without much complaint. The seat is big enough for two, and there are some nicely placed pegs that fold down for two-up riding. The bike is not exactly a ball-of-fire with the extra load aboard, of course, but it will get you there and that is the important thing. Actually, considering the small-displacement, it does rather well when heavily loaded. Two-stroke engines that have not been "tuned" to the ragged edge often show surprising lugging-power when the chips are down.

Some sort of a prize should go to the 150 for its tidy, you might even say fastidious, personal habits. The engine seeps not a drop of oil, and the old two-stroke carburetor fog of fuel and oil has been trapped by the intake-air silencing and filtration system. Even the little bit of oil that sometimes comes from a rear chain has been blocked at its source, with an all-enclosing, stamped-steel housing around the chain. Road-dirt, which can include a bit of water at times, is snared quite nicely by the wide, deeplydrawn fenders. Neat!

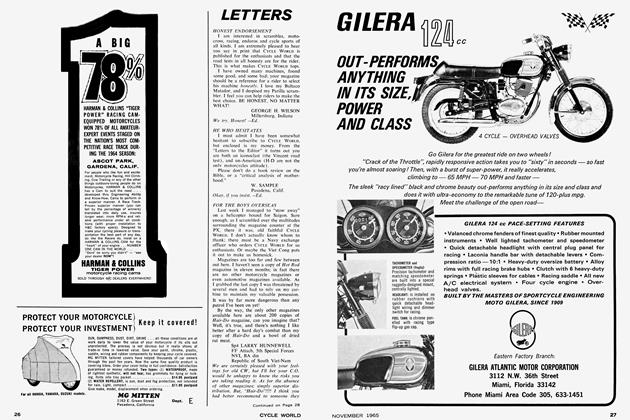

Finish and styling are both appealing. The tank and fenders have that attractive, s.oft-crease look that Japanese motorcycle design has evolved into. Big chromium-plate flashes on the sides of the fuel tank look good, and as they prevent unsightly scratches (if there was paint instead of chrome) are functional as well. And of course there are the usual rubber knee-grips on the tank, too.

What we will remember longest about the Suzuki 150 is the instant-starting, electric-motor smoothness of its engine and bump-absorbing suspension. The springing and damping are probably too soft for ear 'ole riding, but then the 150 was never intended for that kind of thing anyway. Use it for suburban errand-running, or a nice leisurely Sunday-morning touring. There isn't anything else at the price and in the same displacement range that will do that kind of job appreciably better. •

SUZUKI 150 S32-2