how it all began...

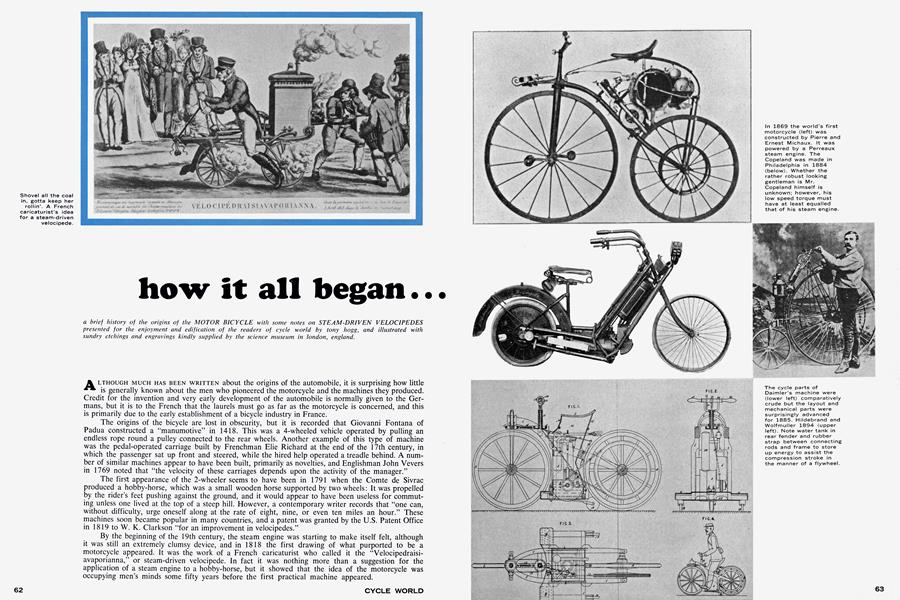

a brief history of the origins of the MOTOR BICYCLE with some notes on STEAM-DRIVEN VELOCIPEDES presented for the enjoyment and edification of the readers of cycle world by tony hogg, and illustrated with sundry etchings and engravings kindly supplied by the science museum in london, england.

A LTHOUGH MUCH HAS BEEN WRITTEN about the origins of the automobile, it is surprising how little is generally known about the men who pioneered the motorcycle and the machines they produced. Credit for the invention and very early development of the automobile is normally given to the Germans, but it is to the French that the laurels must go as far as the motorcycle is concerned, and this is primarily due to the early establishment of a bicycle industry in France.

The origins of the bicycle are lost in obscurity, but it is recorded that Giovanni Fontana of Padua constructed a "manumotive" in 1418. This was a 4-wheeled vehicle operated by pulling an endless rope round a pulley connected to the rear wheels. Another example of this type of machine was the pedal-operated carriage built by Frenchman Elie Richard at the end of the 17th century, in which the passenger sat up front and steered, while the hired help operated a treadle behind. A number of similar machines appear to have been built, primarily as novelties, and Englishman John Vevers in 1769 noted that "the velocity of these carriages depends upon the activity of the manager."

The first appearance of the 2-wheeler seems to have been in 1791 when the Comte de Sivrac produced a hobby-horse, which was a small wooden horse supported by two wheels: It was propelled by the rider's feet pushing against the ground, and it would appear to have been useless for commuting unless one lived at the top of a steep hill. However, a contemporary writer records that "one can, without difficulty, urge oneself along at the rate of eight, nine, or even ten miles an hour." These machines soon became popular in many countries, and a patent was granted by the U.S. Patent Office in 1819 to W. K. Clarkson "for an improvement in velocipedes."

By the beginning of the 19th century, the steam engine was starting to make itself felt, although it was still an extremely clumsy device, and in 1818 the first drawing of what purported to be a motorcycle appeared. It was the work of a French caricaturist who called it the "Velocipedraisiavaporianna," or steam-driven velocipede. In fact it was nothing more than a suggestion for the application of a steam engine to a hobby-horse, but it showed that the idea of the motorcycle was occupying men's minds some fifty years before the first practical machine appeared.

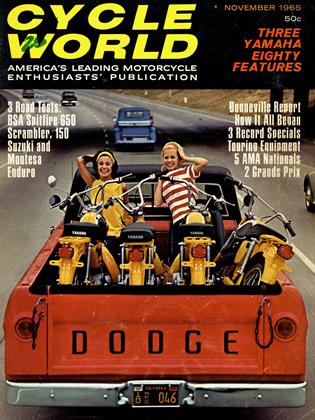

Although various types of treadles connected by linkages to the rear wheel were used extensively at that time, the simple pedal appears to have escaped the minds of the bicycle constructors until about 1860 when a French mechanic named Pierre Lallement hit on the idea. Actually, Lallement never seems to have received credit for the idea because all the glory went to his employers, Pierre and Ernest Michaux, who are remembered in a statue at Bar-le-Duc, France, as the "inventeurs et propagateurs du velocipede a pedale."

The Michaux boys were the founders of the bicycle industry and, by 1868, they were employing over 300 people on the production line in their factory. Meanwhile, Lallement set sail for the New World where, in conjunction with James Carroll of Ausonia, Conn., he took out a patent for the pedal bicycle.

By 1869 Pierre and Ernest Michaux had made their fortunes and sold out to a rival company.

However, as their final fling in that year, they built the world's first motorcycle. This was basically one of their conventional "boneshaker" bicycles fitted with a Perreaux steam engine, and the whole machine has a very sanitary appearance considering that it was motorcycle No. 1,

and that almost a hundred years have passed since its construction.

The engine was a remarkably compact single - cylinder unit which drove the rear wheel by a belt and pulleys. The machine appears to have been quite satisfactory, although one can assume that its range was only a few miles due to its limited water capacity. By this time the steam engine was a highly developed form of motive power, provided all one wanted to do was to haul a freight train or power a factory.

But for automobile or motorcycle use it was necessary to provide a complicated method of metering fuel and water to the engine in order to obtain an adequate range with reasonable economy. The Michaux-Perreaux machine was equipped with none of these devices and, in consequence, it can only be considered as a successful exercise in the application of an engine to a 2-wheeled vehicle.

The Michaux motorcycle was followed quickly by a number of similar machines, including the American Roper which can be seen at the Smithsonian Institute in Washington, D.C. However, it was not until 1884 that the first machines were produced on a commercial scale by another American, L. D. Copeland of Philadelphia. Copeland fitted a steam engine into an American Star bicycle, and followed this up by building about 200 steamdriven tricycles, which must have been the first production run of anything approaching a motorcycle.

Small quantities of steam powered machines were produced by a number of different people until well into the 1890s, when the internal combustion engine finally took over. The demise of steam was due largely to the work of Gottlieb Daimler who constructed a gasoline powered motorcycle in 1885. The frame and wheels of this machine were constructed of wood, and it is evident that Daimler was more interested in the engine than the cycle parts. However, the machine is remarkable in that the basic layout was exactly the same as the conventional layout used today, and it must be remembered that at that time constructors were at a loss to know where to put even the engine.

The engine of Daimler's machine was a single cylinder, air-cooled 4-stroke mounted vertically under the seat. It was designed to run at speeds up to 800 rpm and the design incorporated internal flywheels, a mechanically operated exhaust valve, an automatic intake valve, and a flywheel-driven fan to force air into a shroud surrounding the cylinder. The drive was taken by a flat belt to a countershaft connected by a pinion to an internallytoothed gear mounted inside the rear wheel. This device was ridden by Daimler's assistant Wilhelm Maybach, but it was soon discarded by Daimler who was much more interested in developing the high speed internal combustion engine, primarily for automobile use.

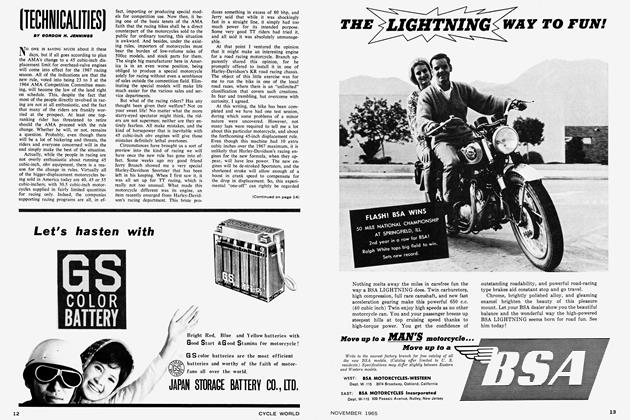

The Daimler motorcycle was followed by a number of different machines, but it was not until 1894 that the first commercially successful motorcycle powered by a gasoline engine was marketed. This was the Hildebrand and Wolfmuller which was made in Munich. The engine was a horizontal twin, with a bore and stroke of 90 x 117mm and the pistons moved in unison, but fired alternately. The external connecting rods were attached through ball bearings to parallel cranks on the rear wheel, and a novel feature was the rubber straps secured between the connecting rods and the frame which were designed to store up energy on the power stroke and assist the compression stroke in the manner of a flywheel. The engine was water cooled and the water was carried in a curved tank which doubled as the rear fender.

The period before 1900 was one of trial and error for the pioneer designers, and there were lots of trials and lots of errors. However, certain names stand out from that period and among them are the wealthy Count Albert de Dion and his partner, George Bouton. The de DionBouton combination had been active since 1883 in construction of vehicles, and in 1895 produced the first high speed internal combustion engine. This engine was capable of running at a sustained speed of 1500 rpm without undue wear and tear, and during the next seven years, in various shapes and sizes, it was used to power a wide variety of different road vehicles, and was manufactured under license by several different companies.

In its original form the de Dion-Bouton was a single cylinder, air-cooled four-stroke with a bore and stroke of 50 x 70mm, although by 1899 a "square" version was available with a bore and stroke of 80mm. The cylinder head with its valve chest was detachable and it was secured by four long studs screwed into the crankcase. The crankcase was aluminum and contained a pair of flywheels with a crank pin between them. The intake valve was automatic and mounted on a detachable seat, and the exhaust valve was operated by a halfspeed gear in the crankcase. De Dion-Bouton paid a lot of attention to ignition and carburetion, which were serious problems in the early days, and although their first engine was equipped with hot tube ignition, later models had a fairly reliable coil and battery system.

In 1889, Edward Butler had invented the carburetor but his "Inspirator," as he called it, was never adopted commercially and the normal method of mixing the fuel and air was by either a surface vaporizer or by some kind of a wick vaporizer. Both systems were highly unsatisfactory but the de Dion-Bouton surface vaporizer was as efficient as you could get in those days. In the ignition department, de Dion-Bouton used a coil with primary and secondary windings energized by a 4-volt battery and triggered by a contact breaker driven from the cam gear, and the popularity of these engines was undoubtedly due in part to the relative efficiency and reliability of their carburetion and ignition systems.

Working along the same lines as de Dion-Bouton were the brothers Michel and Eugene Werner, who were of French nationality but Russian extraction. The Werner motorcycle of 1899 was actually a bicycle with a motor attached, but it was successful commercially and its design and construction were extremely simple and compact. The 217cc aircooled engine unit weighed 65 lbs. and it was mounted on the steering head driving the front wheel by means of a twisted rawhide belt. However, the high center of gravity, combined with the bad roads of the time, made the machine difficult to handle, so in 1902 the Werners produced another very successful model with a 262cc engine mounted in the conventional manner. Once again the design was very clean and such features as a spray carburetor, de Dion-Bouton ignition, forced lubrication by hand pump, and a foot brake operating on the rear wheel made it perhaps the first really satisfactory production motorcycle.

(Continued on page 100

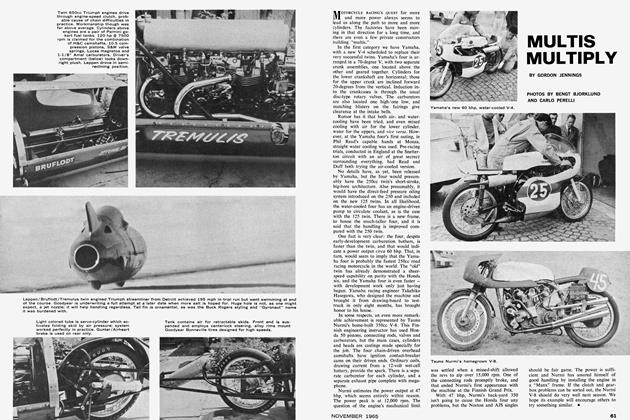

Machines, such as the Werner, were quite sophisticated but sadly lacking in performance. Therefore the next step was to increase cylinder capacities, resulting in such machines as the Triumph in England and the Indian in America, and finally the multi-cylinder engine was introduced. The V-twin is, of course, a natural for motorcycle applications and it was adopted very early by JAP in England and Harley-Davidson in America, among others. Meanwhile, Werner produced a vertical twin in 1905 but it does not appear to have been accepted, and this particular layout was not introduced successfully until 1935.

In 1965 we tend to think of the 4-cylinder motorcycle as something very exotic and of little practical value except as a weapon for winning races. However, four cylinders became quite common around 1905, and the first recorded example was the Binks of 1903. By far the most successful four was the Belgian F.N., which was introduced in 1905

This machine was powered by an in-line aircooled 4-cylinder with a bore and stroke of 45 x 57mm giving a capacity of 363cc. The four-throw crankshaft was supported by three main bearings and the crankcase was split longitudinally. The connecting rods ran on plain bearings, lubrication was by splash, and the oil level in the crankcase could be checked by individual inspection windows. The F.N. soon established a reputation for reliability and smooth running and it was notable for such advanced features as shaft drive, Bosch magneto, telescopic forks, and by 1909 it had a multi-plate clutch in the flywheel driving a 2-speed gear in the shaft drive casing.

Considering that Pierre and Ernest Michaux produced the first motorcycle in 1869, and that it appears to have been quite a satisfactory machine, it is surprising that another 25 or 30 years should pass before the motorcycle became a commercial possibility. The reason seems to lie in the problems associated with carburetion, ignition, tires, brakes, and all the other components that make up a motorcycle, to say nothing of public opposition and the condition of the roads.

In an era of electric starters, rear suspension, battery and generator lighting, and everything else that we now take for granted, it is difficult to imagine the problems confronting the early pioneers, and many oldtimers will tell you that a lot of the sport has gone out of motorcycling. Personally, I am reluctant to agree, but if anyone knows where there is a steamdriven velocipede for sale, I can be reached at any time care of CYCLE WORLD. •