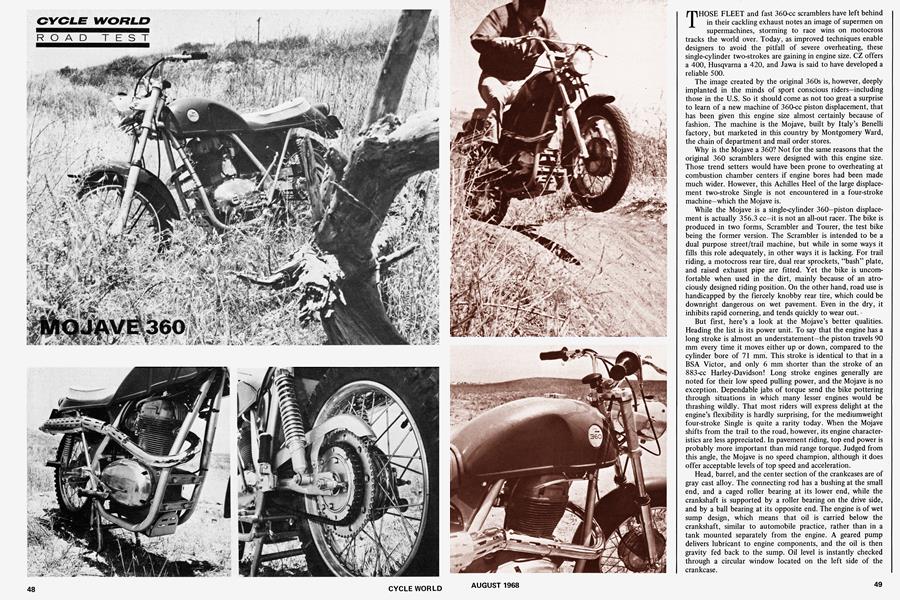

MOJAVE 360

CYCLE WORLD ROAD TEST

THOSE FLEET and fast 360-cc scramblers have left behind in their cackling exhaust notes an image of supermen on supermachines, storming to race wins on motocross tracks the world over. Today, as improved techniques enable designers to avoid the pitfall of severe overheating, these single-cylinder two-strokes are gaining in engine size. CZ offers a 400, Husqvarna a 420, and Jawa is said to have developed a reliable 500.

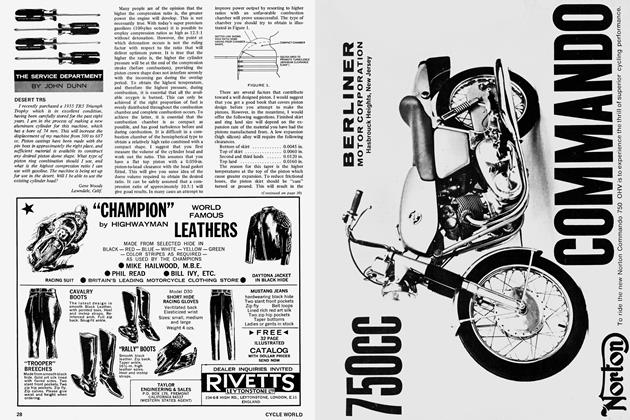

The image created by the original 360s is, however, deeply implanted in the minds of sport conscious riders—including those in the U.S. So it should come as not too great a surprise to learn of a new machine of 360-cc piston displacement, that has been given this engine size almost certainly because of fashion. The machine is the Mojave, built by Italy's Benelli factory, but marketed in this country by Montgomery Ward, the chain of department and mail order stores.

Why is the Mojave a 360? Not for the same reasons that the original 360 scramblers were designed with this engine size. Those trend setters would have been prone to overheating at combustion chamber centers if engine bores had been made much wider. However, this Achilles Heel of the large displacement two-stroke Single is not encountered in a four-stroke machine—which the Mojave is.

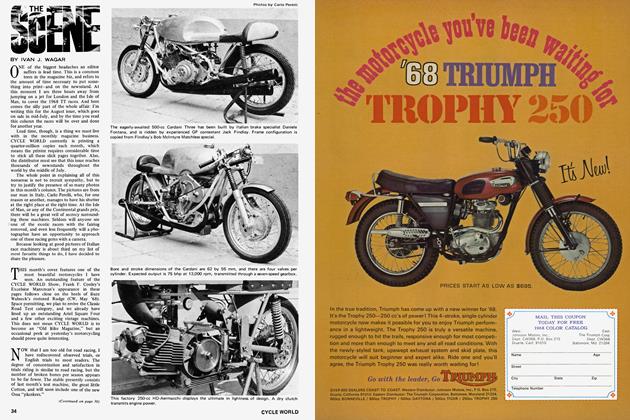

While the Mojave is a single-cylinder 360—piston displacement is actually 356.3 cc—it is not an all-out racer. The bike is produced in two forms, Scrambler and Tourer, the test bike being the former version. The Scrambler is intended to be a dual purpose street/trail machine, but while in some ways it fills this role adequately, in other ways it is lacking. For trail riding, a motocross rear tire, dual rear sprockets, "bash" plate, and raised exhaust pipe are fitted. Yet the bike is uncomfortable when used in the dirt, mainly because of an atrociously designed riding position. On the other hand, road use is handicapped by the fiercely knobby rear tire, which could be downright dangerous on wet pavement. Even in the dry, it inhibits rapid cornering, and tends quickly to wear out. -

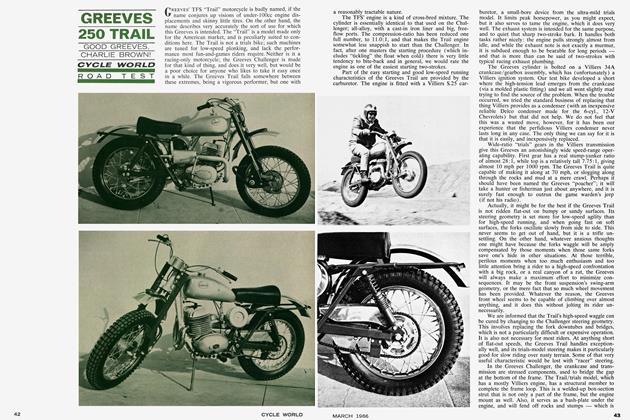

But first, here's a look at the Mojave's better qualities. Heading the list is its power unit. To say that the engine has a long stroke is almost an understatement—the piston travels 90 mm every time it moves either up or down, compared to the cylinder bore of 71 mm. This stroke is identical to that in a BSA Victor, and only 6 mm shorter than the stroke of an 883-cc Harley-Davidson! Long stroke engines generally are noted for their low speed pulling power, and the Mojave is no exception. Dependable jabs of torque send the bike pottering through situations in which many lesser engines would be thrashing wildly. That most riders will express delight at the engine's flexibility is hardly surprising, for the medium weight four-stroke Single is quite a rarity today. When the Mojave shifts from the trail to the road, however, its engine characteristics are less appreciated. In pavement riding, top end power is probably more important than mid range torque. Judged from this angle, the Mojave is no speed champion, although it does offer acceptable levels of top speed and acceleration.

Head, barrel, and the center section of the crankcases are of gray cast alloy. The connecting rod has a bushing at the small end, and a caged roller bearing at its lower end, while the crankshaft is supported by a roller bearing on the drive side, and by a ball bearing at its opposite end. The engine is of wet sump design, which means that oil is carried below the crankshaft, similar to automobile practice, rather than in a tank mounted separately from the engine. A geared pump delivers lubricant to engine components, and the oil is then gravity fed back to the sump. Oil level is instantly checked through a circular window located on the left side of the crankcase.

The Mojave's brakes—single leading shoe units on both front and rear wheels—are powerful enough to halt the bike in a very short distance with light lever pressures and without grab. On the trail they are more than adequate. The rear brake is easily locked in dirt riding, but this is a feature a rider can learn to avoid. Likewise, front and rear suspension also are suited to both road and trail. The tall, fully chromed front fork, equipped with neat rubber dust excluders a la Ceriani, and single acting shock absorbers, evens out the roughest of off-road going, although the rear units are a little more harsh in operation.

In its basic configuration, the tubular frame bears a certain similarity to Rickman Metisse practice. A full cradle is formed by the twin toptubes and downtubes, which cross over near the steering head, so that the toptubes actually meet the head at its lowest point. Like the Metisse frame, the toptubes are linked by a short crosstube, from which another tube extends to the steering head. Very wide diameter tubing is used throughout, and combined with the battleship gray paint color, gives the frame a somewhat bulky appearance. Even as far rearward as the taillight housing, tubing diameter is identical to that in the main frame section. The swinging arm pivots on bushings, and is located by sections of gusseting welded to the rear frame legs. Quality of all frame welds is among the highest encountered on Italian motorcycles, and the neatness suggests that an automatic electric arc welding machine has been used. General finish of the bike is also high—stampings are clean and tidy, and paint is well applied.

While both frame and suspension are excellent, the Mojave gives a strong hint that its handling would be still better, but for certain faults that greatly affect overall performance. Its major handicap is that while the riding position is comfortable for the street, it is surely among the worst ever built into a bike intended for trail use. The high level exhaust pipe juts out several unnecessary inches from the side of the machine, so that it constantly interferes with the rider's right leg. Moreover, heat from the pipe is conducted into the guard plates that should protect the rider. The result is that the right leg is forced to the outside of the footpeg, a clumsy position for any type of riding. As one unkind wit commented: "I don't know whether my leg should go inside or outside of the exhaust pipe!"

For street use, the handlebar is fine, but for trail riding, it is too high and narrow, and the relationship between footpegs

and handlebar is such that the rider is mounted too far forward when he is standing up. Also, the handlebar is not wide enough for grappling with the bumps and jolts of rapid dirt riding.

Center of gravity is a vital matter in a machine that is intended to handle well on the trail. The lower the major components are placed, the more predictably a bike will corner. The Mojave offends badly in this respect. A two-stroke has no valve gear to carry above its barrel, and a twin-cylinder engine is naturally shorter than a Single. The unfortunate Mojave has neither of these benefits. Its long stroke engine sits tall, and its height is increased still more by the oil sump. As a result, the frame also is forced into a high configuration, and the bike suffers from top heaviness, a characteristic that is very noticeable in the dirt, less so on the road. The effect might be reduced if the fuel tank, seat mounting and side panels were of alloy or fiberglass, but instead they are formed of steel.

Gear changes are accomplished through a rocking pedal mounted on the right side. The gap between low and second gears is wide, as is shown by their ratios of 21.6 and 11.68, using the "fast" sprocket. Fortunately, the engine's flexibility helps to overcome the jump. The top three ratios are well matched. The bike's flexible power range also meant that off-road use was enjoyable even without changing to the "slow" sprocket. The major fault with the gearbox lies in the change mechanism. Neutral is between low and second gears, but false neutrals between other gears can be found unless a fairly harsh foot movement is used. Fast gear shifts require an even more vicious stabbing movement.

Power is transmitted from the engine to the clutch by helical gears. The clutch, a conventional multi-plate unit, is light in operation.

Electrics on the Mojave are catered for by a 6-V, 60-watt generator and battery, which is housed under the seat. In addition to the ignition key, there is a steering lock. The speedometer is located in a conventional position in the headlamp shell, but is so badly obscured by brake and clutch cables and the handlebar strengthening brace, that it might almost not be there. The speedometer face is calibrated to a tremendously optimistic 100 mph, but is numbered only at intervals of 20 mph.

One or two minor grumbles remain to be aired. The Mojave is an erratic starter, whether the engine is hot or cold. Besides a tickler for the float chamber, the Dellorto carburetor is also fitted with a manually operated choke slide. Varying techniques were used to start the bike, but sometimes it chose to play stubborn, for no apparent reason. Both sets of footpegs are folding, but the rearmost pair are attached by metal tabs which bolt to the frame. They gave no trouble during the test, but a more robust method of location would be better.

The Mojave series of machines marks Montgomery Ward's most serious attempt to penetrate the American market, although the company has been selling motorcycles for some years. Sister machine to the Mojave Scrambler is the Mojave Tourer, which costs $50 less. There also are 260-cc Scrambler and Tourer Mojaves—again made by Benelli—each available at $100 less than their 360-cc equivalents. All machines can be bought either from a Montgomery Ward store, or by mail order, in which case the bike arrives almost fully assembled, in a crate. Front wheel and fender, handlebar and controls and battery are the only items the buyer must mount himself. Incidentally, the Montgomery Ward Mojave has no connection or relationship with a machine of a similar name (CW, June '68). That bike was a pure competition mount, powered by a Japanese engine, and assembled by a group of people with considerable experience in racing automobiles. ■

MOJAVE 360

$899