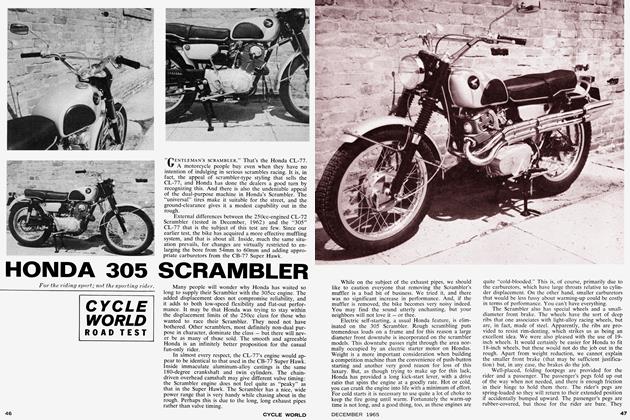

CYCLE WORLD ROAD TEST

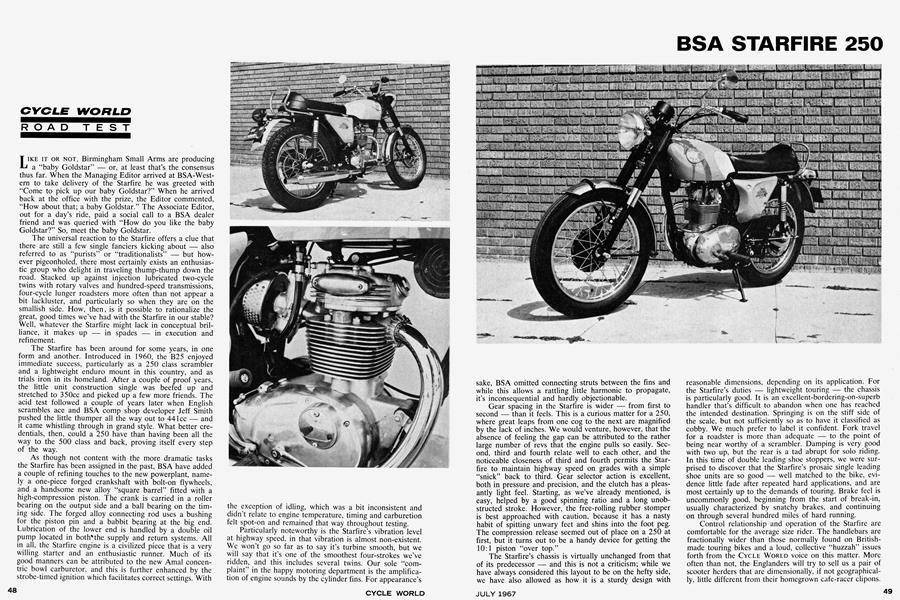

LIKE IT OR NOT, Birmingham Small Arms are producing a “baby Goldstar” — or, at least that’s the consensus thus far. When the Managing Editor arrived at BSA-Western to take delivery of the Starfire he was greeted with “Come to pick up our baby Goldstar?” When he arrived back at the office with the prize, the Editor commented, “How about that; a baby Goldstar.” The Associate Editor, out for a day’s ride, paid a social call to a BSA dealer friend and was queried with “How do you like the baby Goldstar?” So, meet the baby Goldstar.

The universal reaction to the Starfire offers a clue that there are still a few single fanciers kicking about — also referred to as “purists” or “traditionalists” — but however pigeonholed, there most certainly exists an enthusiastic group who delight in traveling thump-thump down the road. Stacked up against injection lubricated two-cycle twins with rotary valves and hundred-speed transmissions, four-cycle lunger roadsters more often than not appear a bit lackluster, and particularly so when they are on the smallish side. How, then, is it possible to rationalize the great, good times we’ve had with the Starfire in our stable? Well, whatever the Starfire might lack in conceptual brilliance, it makes up — in spades — in execution and refinement.

The Starfire has been around for some years, in one form and another. Introduced in 1960, the B25 enjoyed immediate success, particularly as a 250 class scrambler and a lightweight enduro mount in this country, and as trials iron in its homeland. After a couple of proof years, the little unit construction single was beefed up and stretched to 350cc and picked up a few more friends. The acid test followed a couple of years later when English scrambles ace and BSA comp shop developer Jeff Smith pushed the little thumper all the way out to 441cc — and it came whistling through in grand style. What better credentials, then, could a 250 have than having been all the way to the 500 class and back, proving itself every step of the way.

As though not content with the more dramatic tasks the Starfire has been assigned in the past, BSA have added a couple of refining touches to the new powerplant, namely a one-piece forged crankshaft with bolt-on flywheels, and a handsome new alloy “square barrel” fitted with a high-compression piston. The crank is carried in a roller bearing on the output side and a ball bearing on the timing side. The forged alloy connecting rod uses a bushing for the piston pin and a babbit bearing at the big end. Lubrication of the lower end is handled by a double oil pump located in both'the supply and return systems. All in all, the Starfire engine is a civilized piece that is a very willing starter and an enthusiastic runner. Much of its good manners can be attributed to the new Amal concentric bowl carburetor, and this is further enhanced by the strobe-timed ignition which facilitates correct settings. With the exception of idling, which was a bit inconsistent and didn’t relate to engine temperature, timing and carburetion felt spot-on and remained that way throughout testing.

Particularly noteworthy is the Starfire’s vibration level at highway speed, in that vibration is almost non-existent. We won’t go so far as to say it’s turbine smooth, but we will say that it’s one of the smoothest four-strokes we’ve ridden, and this includes several twins. Our sole “complaint” in the happy motoring department is the amplification of engine sounds by the cylinder fins. For appearance’s sake, BSA omitted connecting struts between the fins and while this allows a rattling little harmonic to propagate, it’s inconsequential and hardly objectionable.

BSA STARFIRE 250

Gear spacing in the Starfire is wider — from first to second — than it feels. This is a curious matter for a 250, where great leaps from one cog to the next are magnified by the lack of inches. We would venture, however, that the absence of feeling the gap can be attributed to the rather large number of revs that the engine pulls so easily. Second, third and fourth relate well to each other, and the noticeable closeness of third and fourth permits the Starfire to maintain highway speed on grades with a simple “snick” back to third. Gear selector action is excellent, both in pressure and precision, and the clutch has a pleasantly light feel. Starting, as we’ve already mentioned, is easy, helped by a good spinning ratio and a long unobstructed stroke. However, the free-rolling rubber stomper is best approached with caution, because it has a nasty habit of spitting unwary feet and shins into the foot peg. The compression release seemed out of place on a 250 at first, but it turns out to be a handy device for getting the 10:1 piston “over top.”

The Starfire’s chassis is virtually unchanged from that of its predecessor — and this is not a criticism; while we have always considered this layout to be on the hefty side, we have also allowed as how it is a sturdy design with reasonable dimensions, depending on its application. For the Starfire’s duties — lightweight touring — the chassis is particularly good. It is an excellent-bordering-on-superb handler that’s difficult to abandon when one has reached the intended destination. Springing is on the stiff side of the scale, but not sufficiently so as to have it classified as cobby. We much prefer to label it confident. Fork travel for a roadster is more than adequate — to the point of being near worthy of a scrambler. Damping is very good with two up, but the rear is a tad abrupt for solo riding. In this time of double leading shoe stoppers, we were surprised to discover that the Starfire’s prosaic single leading shoe units are so good — well matched to the bike, evidence little fade after repeated hard applications, and are most certainly up to the demands of touring. Brake feel is uncommonly good, beginning from the start of break-in, usually characterized by snatchy brakes, and continuing on through several hundred miles of hard running.

Control relationship and operation of the Starfire are comfortable for the average size rider. The handlebars are fractionally wider than those normally found on Britishmade touring bikes and a loud, collective “huzzah” issues forth from the CYCLE WORLD voice on this matter. More often than not, the Englanders will try to sell us a pair of scooter herders that are dimensionally, if not geographically, little different from their homegrown cafe-racer clipons. But, wonder of wonders, the Starfire has an honest to goodness set of handlebars fitted to its headcrown. Perhaps this all seems a bit like quibbling, but we Yanks are usually given handlebars that the old-country folks are sure we will like, and they are usually about as comfortable as oval steering wheels.

With those bars and the new BSA family line seat, the Starfire feels as good as one’s friendliest motorcycle. The twin seat is as firm and comfortable for two as it is for one, and its styling is beginning to get to us; it seemed a trifle pretentious at first, what with its road racer backside and all, but we’ve come to consider it a handsome addition to this attractive motorcycle. The finish and detailing on the Starfire are excellent, and we would venture to say some of the best in the BSA line. This seems curious, when one considers that BSA market motorcycles selling for almost twice as much as the Starfire; but the Starfire is still one of the best finished in the line.

If the Starfire’s finish were not enough to make it attractive to the buying public, the glasswork would certainly be strongly persuasive. The tool box cover and remote sump are crisp, sharp design elements that contribute much to the Starfire’s aesthetic zest. The fuel tank is a delight — one of the prettiest to be found, blending nicely into the seat. And in keeping with the current and most welcome trend in the area of supporting pieces, these items are fashioned of fiberglass in such good style that we are wondering whether or not the British might know almost as much about wonder-fab as we do.

One area that the Starfire is sure to make friends in is that of lighting. Not only does the little dude have ample candles to get you safely down the road, but it will also make everyone happy with the stored electrical energy on tap for illuminating and signalling. The only piece of electrical equipment that is of questionable value or accuracy, by the way, is the ammeter whose sole function — it would seem by its frantic and constant gyrations — is to tell you that your engine’s running.

We have hardly any quarrels with the Starfire, and these are minor. With reference to the total picture we must say that the BSA 250 is a superb little bike — not quite as dramatic in its performance as some of the transpacific imports — but nevertheless a real motorcycle that is going to remind a lot of sophisticates that those chaps across the pond still have some idea what motorcycling is all about. ■

BSA "STARFIRE” 250cc